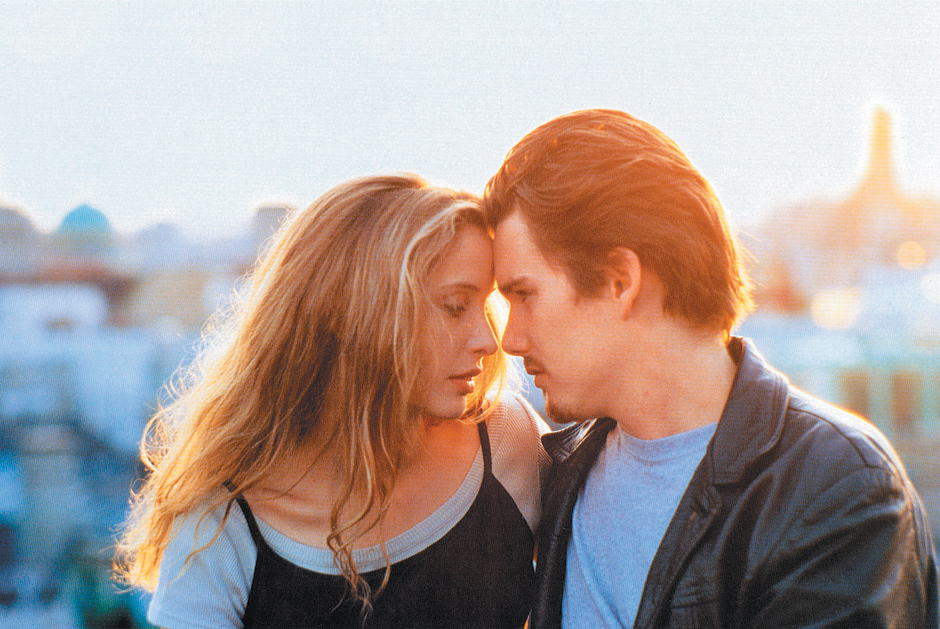

Before Midnight extends Richard Linklater’s extraordinary sequence of films, begun eighteen years ago with Before Sunrise and continuing, nine years later, with Before Sunset. The films follow the ups and downs of a young couple, Céline and Jesse, played by Julie Delpy and Ethan Hawke. They first meet at the same moment we first meet them, on a train crossing Europe, and part (promising to meet back in Vienna six months hence) fourteen hours of their time and almost two hours of our time later, just in time to end Before Sunrise. Many people who saw the film when it appeared in 1995 wondered, some months later, what Céline and Jesse would have been up to. How could things work out? It was too soon for a sequel.

When the second film, Before Sunset, arrived nine years later, I half-hoped that it would chronicle that reunion in Vienna, though it was hard to be optimistic. Instead the film opens in Paris, at Shakespeare and Company, where Jesse, on a book tour to promote a novel called Before Sunrise, answers the gathered crowd’s prurient questions: How much of the novel was real? Does the couple meet again as they’d promised? Jesse won’t say, though the answer has to be no, since, already at this point, we suspect that Linklater’s idea is that we should feel our own experience of Jesse and Céline is perfectly congruent with their experience of each other: meeting when they meet, parting when they part, going about our lives for nine years without them as they do without each other. And so, no surprise, since we’re back, they’re back: Céline appears in the rear of the store and the film is underway.

Before Sunset took place entirely in the narrowing interval before Jesse’s plane departs for the States, where a wife and young son expect him. Another good-bye looms; the couple keeps pushing the deadline back, claiming more and more of that ninety or so minutes for themselves. The film looks as though it will end at several points, but the characters conspire to lengthen it. In the end, there is no good-bye: this time Céline and Jesse will get more time with each other than we get with them. They talk and laugh and flirt in Céline’s apartment in Paris, and then the screen goes dark. It is as though they noticed we were peering at them and abruptly pulled the shades.

Their existence in overtime could last an instant, it could last an eon: but in any case, the couple now has an existence beyond the interval of filmed time. The details are a little too convenient: Jesse is in a loveless marriage and Céline has a boyfriend who travels. They’re going to stick together, it’s clear. Because they seem to transcend their own fictionality (for the viewer and, in the third film especially, for each other), it feels as though they will collaborate on their future, off-screen and away from the deterministic tick-tock of these films. The true deadline in Before Sunset was the end of the movie: we saw it coming and we saw it pass. And so another nine years has passed before the appearance of this new film, which, one half-expects, will lead, nine years from now and not before, to another film, and then another. Part of their power rests in the brutal shortening of mortal life if it is measured not in months or years but in nine-year increments with nonexistence in between. Nobody who saw the first one in the theaters has more than a handful of these movies left in him.

Nine years later, in Before Midnight, released last year, Jesse and Céline’s life is well underway, and the new open-endedness of their time together is bound up with costly sacrifice. Since they’ve had nine years to themselves, they seem, again, “real,” though in a new way: reality once meant we could verify their every gesture; now they have a past we will learn about only secondhand. They seem all too real, obstinately real, to one another: the film right away introduces a new tone of irascibility or pique between them.

The son who Jesse spoke of loving so much in the second film, now in his teens, is dispatched, in the movie’s first sequence, back home to America after the summer in Europe with his dad. Céline and Jesse are now accompanied by their two adorable twin girls; a long tracking shot follows them as they drive through the Peloponnesian countryside, the kids asleep in the back. This seeming idyll depends on Linklater’s having financed and made (at the last minute, he has suggested) a film that might not have been made, since the only reason to make it at all is to make it on time. If two monkeys or parakeets or alligators were in the car, it wouldn’t surprise us: Céline and Jesse’s scrape with nonexistence seems something out of the story of Noah.

Advertisement

The films have always been about the marvels and limitations of impersonation, since behind Jesse and Céline we see Hawke and Delpy, celebrities whose stars were bright already in the first film and have intensified, owing partly to this series, ever since. Time shows on their faces. Their characters differ about how to present their story to outsiders, almost like cowriters working on a script. (In fact, Hawke and Delpy collaborated on the scripts of the second and third films.) They contest one another’s accounts of their past. They are now famous, Jesse for his novels, Céline for her role in his novels; the characters have caught up to the actors, who, in real life, are probably best known for playing these characters (whatever else Hawke and Delpy do, they will always be linked to each other and these films).

Much about the new film sends us back to the first one, which, eighteen years ago, may uncannily seem to have looked ahead to this film. The characters obsessively replay their origins: Céline wonders if Jesse, traveling back in time, would still have fallen for her on the train where she was reading a book by the highbrow writer on the erotic, Georges Bataille; Jesse asks whether that wouldn’t technically constitute “cheating on her with her.” The right way to view Before Sunrise is, having seen it eighteen years ago, to go see the third film Before Midnight and then watch Before Sunrise again; the self-consciousness of the two characters was there from the start.

Because of its radical circularity—the third film referring back to the first; the first film oddly forecasting the third—there is no true “beginning” to Linklater’s trilogy, which suggests that we are ahead of ourselves even when we seem to be running behind. In Before Sunrise, Jesse gets Céline to detrain in Vienna with a pitch about time travel: if she doesn’t learn now what a disappointment he is, “ten or twenty years from now” she will measure her future husband against the unfulfilled possibility that he, Jesse, represented. The entire series is catalyzed by this couple’s imagination of their pasts as viewed from their futures.

And yet the strange chemistry of the pair, utterly real but based in dialogue both parties often seem to regard as hammy, tinny, or pretentious, suggests how little control over passing time they have, even as the forfeiture of control takes the form of seeming “freedom.” What a strange movie couple they make. It doesn’t matter what they say to one another, and much of what they say is rather clumsy, dopey, or vague. Their rapport is so real that what they say doesn’t matter. The game is to try to seem, to one another and to the viewer, perfectly natural and authentic; verbal skirmish and repartee are the kinds of things lovers in the movies do to pass the time. Anyone seeing these films supposes they are improvised; in fact, they are completely scripted, with many rehearsals and takes to get everything looking perfectly thrown together. It makes you think about the ways “real life” is depicted, the conventions that govern what we accept, in the movies, as real and spontaneous.

In Before Sunrise, the two of them have different destinations, which is the same as saying they have different pasts: Delpy is headed home to Paris, but not in any urgent way; Hawke, whom we later learn has just been dumped by his girlfriend in Barcelona, has been traveling around on a Eurail pass and has a flight home to the US out of Vienna the next morning. The train is therefore the embodiment of passing time—for the young people, for us—bringing every character relentlessly nearer the end. The solution to passing time is therefore simple: you get off the train, but then another, later end (which, as we innately understand, will also be the end of the film) awaits, presenting you with another, later opportunity to go into overtime (no movie has ever been more obviously predestined, from the first frame, to end in a cliffhanger).

But when they get off the train in Vienna, something profound has happened. To be sure, they have temporarily cheated time by “finding” an unsought fourteen hours of it, together in a foreign city; but they have also hastened their separation: they have stepped into a movie. Fourteen hours of Jesse and Céline time now has to fit into the remaining hour and change of movie time—the standard duration of mainstream American films, felt by every moviegoer in his bones, being no more than two hours or so. By elongating time, they have in fact shortened it in ways they can see: they talk about ways of losing time, in drugs or drinking or—as Céline suggests—in “fucking”; soon after that word is uttered, time is lost and we rejoin them at dawn, walking the desolate Vienna streets and talking, no surprise, about time:

Advertisement

Jesse: What’s the first thing you’ll do when you get back to Paris?

Céline: Call my parents.

Jesse: Yeah?

Céline: What about you?

Jesse: I don’t know…I’ll probably go pick up my dog. He’s still with a friend of mine.

Céline: You have a dog?

Jesse: Yeah.

Céline: I love dogs.

Jesse: You do?

Céline: Yeah.

Jesse: Oh shit!

Céline: What?

Jesse: Oh, I don’t know. We’re back in real time.

Céline: I know. I hate that.

Though they are comically “alert” to everything in Vienna, ogling the bridges and byways, engaging the batty locals, there is one big detail they never notice and we never see: the Steadicam that tracks them from only a few feet ahead in single-take shots of unusual duration. The camera’s invisibility is a basic fact of most fictional films, but we have now crossed over into what feels like documentary and the characters’ blindness to the giant eye staring straight at them feels suddenly nearly tragic. What started as a film that offered all the pleasures of eavesdropping now has a creepy voyeurism, almost like an act of surveillance. Over the course of the evening, they have decided they will have only this one night together—no exchange of numbers or information, no plans for the future. But the future doesn’t care about anyone’s plans to ignore it, and by the end of the film the two of them have rushed through their ingenious extension. By arranging their next meeting they appear to have arranged their own sequel.

When Jesse and Céline meet again in Paris in Before Sunset, it is another “chance” encounter that has in every sense been staged. Jesse has become a novelist, traveling in support of his book, a fictional account of his one night with Céline; later he tells her he wrote the book so that he could find her, a statement that rings entirely true to her. Just as she used her book by Georges Bataille as bait on that train outside Vienna, so Jesse has dangled his book, which, we are told, ends, like the first film, with a cliffhanger.

Appearing in this second film, they are now more than ever “characters”—like Bond or Charlie Chan—expecting of each other the kind of reliable responses and attitudes we expect of them. But they are also, in different ways, authors, arranging their own chance encounters, choreographing the illusion of coincidence, embarking on a new beginning with a built-in ending. Their “real” lives these last nine years without each other have been, they say—no surprise—a lie; whether they are lying about that to give this one fictional moment the air of reality remains an open question.

Before Sunset is a great film, great for the ways it transforms and enlarges the conceit of the single night together to allow for years of elapsed time. The characters are as surprised to see each other as we are to see them, and equally as panicked about having to say good-bye again, for a span that is now set at nine years. Again Céline and Jesse just walk and talk, again saying and doing nothing memorable, though when Delpy hugs Hawke at the end of the film, you feel more or less what he feels (in the movies when people embrace, you rarely feel that you have been embraced).

Jesse has kept his looks, but he looks like hell—he is a gaunt and pale fashion victim in the world’s most unfortunate shirt. Delpy is radiant, in ways neither Hawke’s character nor the audience can quite believe: whatever was merely gamine about her the first time around has become otherworldly and classic. She has the spotlight for almost the entire film, though the camera placidly, evenly, registers them both; he shrugs or makes lame jokes and clueless “American” remarks (“I love these old staircases”), but this is her film, and Jesse has an almost comic sense of himself as being mismatched. Céline can see this and is drawn to it; she is the narcissist of the two, though he looks as though he spends more time in front of the mirror.

Before Sunset was an instant addition to the small corpus of classic real-time movies, as smart in its manipulation of the device as Rope, High Noon, or the great Agnès Varda film Cléo from 5 to 7. It was also to my knowledge the first real-time sequel in real time, its eighty-minute sliver of time happening right on time, nine years later. The characters seem to have arranged, through the mechanisms of film itself, especially the “cliffhanger,” their own survival. Think of all the astonishing people we’ve met in the movies, to lose them forever or to meet them again only by reanimating them by the funereal action of rewatching the film.

Céline and Jesse met the moment we met them; here they re-meet at the exact instant we, too, re-meet them. Linklater’s long takes in real time suggest a route through Paris anyone could walk, though in fact the route is stitched together from several picturesque stretches of the Latin Quarter and the Bastille. Do we go where they go? Or do they, following a path only the movies could make plausible, go where we go: along the streets of a Paris oddly cleared of its inhabitants, as though for the filming of a movie?

Before Sunrise was a film about two people trying to regard the present as independent of either past or future; when they get off the train, Céline and Jesse go to an amusement park full of carousels and Ferris wheels, embodiments of cyclicality and uncanny return. Their first kiss is on the Ferris wheel. But the future keeps popping up in inconvenient ways, as it does whenever people try, by an act of will, to live in the moment. (The lovers fight only once in the movie, and it is about a prophecy told to them by a gypsy palm-reader in a café.)

Before Sunset is all about the past, or, to be more precise, about past futures: at one point Jesse laments that, had they met up in Vienna six months later as they had vowed (he went; she claims her grandmother in Budapest was sick), everything might have been different for them. But those possible futures are now relics of the past, like everything else in this movie set with the sun going down, with youth itself imagined as a series of possibilities foreclosed.

These movies are filled with meditations about time, but what sticks with you is not the deep thoughts Jesse and Céline express but simply the spectacle of people contemplating the very element that immerses them, as though they were separate from it: like a fish contemplating water. In the bookstore scene that opens Before Sunset, one of the French journalists asks Jesse about his next project. This is his response:

Ah…I don’t know, man, I don’t know…I’ve been…I’ve been thinking about this…. Well, I always kind of wanted to write a book that all took place within the space of a pop song, you know, like three or four minutes long, the whole thing.

The story, the idea is that…there’s this guy. Right? And…he’s totally depressed. I mean, his great dream was to be a lover, an adventurer, you know, riding motorcycles through South America, and instead he’s sitting at a marble table, eating lobster, and he’s got a good job and a beautiful wife, right? But you know, everything that he needs. But that doesn’t matter, ’cause what he wants is to fight for meaning.

You know, happiness is in the doing, right, not in the…getting what you want. So, he’s sitting there, and just at that second, his little five-year-old daughter hops up on the table. And he knows that she should get down ’cause she could get hurt, but she’s dancing to this pop song, in a summer dress. And he looks down, and all of a sudden, uh, he is sixteen. And…his high school sweetheart is dropping him off, at home. And they’ve just lost their virginity, and she loves him, and the same song is playing on the car radio, and she climbs up and starts dancing on the roof of the car. And now, now he’s worried about her! And she’s beautiful, with a…a facial expression just like his daughter’s. In fact, you know, maybe that’s why he even likes her.

You see, he knows he’s not remembering this dance, he’s there. He’s there in both moments simultaneously. And just like for an instant [snaps his fingers], all his life is just folding in on itself and it’s obvious to him that time is a lie…. [Jesse motions to his right, and sees Céline standing against the wall, listening to him.] Uh…that it’s all happening all the time and inside every moment is another moment, all…you know, happening simultaneously.

This is an idea that Linklater shares, one of the many moments in these films when a character seems uncannily aware of the fictional box he’s trapped inside. Linklater’s stunning animated film Waking Life from 2001 featured a cameo by Céline and Jesse: lying in bed in a comfortable apartment, things seem to have worked out for them—but when? Three years later, in Before Sunset, they meet again, lamenting, for the entire film, the missing years. Fans of Linklater thought they knew better: they were in bed much of the time, imagining what difference it would make if they were unreal, like figments in an old woman’s dreams of her youth. Of course they were precisely unreal and figments in the collective dream we call the movies, a fact that, as characters, they seem constantly on the verge of understanding. It is a guarantee of their reality that they so openly contemplate the possibility that they are made up.

But all of these assertions about simultaneity and the “lie” of time happen as time is passing, as the characters age and we age. The only way to represent this paradox is to do what Linklater has done, spacing his films at long and regular intervals but keeping the actors and conversations more or less stable. The series promises to become a study of fictional characters over the years, of actors as they age on film, and of us, at least those of us old enough to have seen all the movies when they appeared and young enough to be likely to see many more if and when they arrive. (That precise age is Jesse and Céline’s age, also more or less my age, forty-one.)

The movies inspire both a personal response and a fear that one’s response is too personal, just as they seem to conscript us into the kind of philosophizing that sometimes bogs Jesse and Céline down. The ways that all the parties coincide—viewer with actor with character—is of course an accident of the present, a feature that requires us to register a personal response. So many people who have written on these films have commented on their effect of overlaying the fictional Jesse and Céline on the lives of Hawke and Delpy and on their own lives. I feel almost required to note the time (11 AM) and date (June 7, 2013) and location (Coolidge Corner Theater, Brookline, Massachusetts) when and where I first saw Before Midnight. It was some kind of moms-and-babies screening: infants wailed and were comforted in the rows around me, palpably annoying the otherwise mainly elderly crowd. I was equally drawn to and repelled by the characters on the screen and the real people, mewling and squirming, in the seats of the theater.

There is a remarkable scene in Before Midnight where Jesse and Céline, checking into a hotel their last night in Greece, are both asked, by a fan, to sign Jesse’s books about their past. Characters aren’t authors, and so rarely get asked to inscribe the books in which they are featured. Céline at first refuses: how strange, she thinks, and also how offensive to have her entire existence subjugated to her husband’s account. In the end, they both sign; why shouldn’t they? It is as though, through the scrim of Linklater’s direction, now coming closer than ever to documentary reality, the two actors have been spotted lurking behind their masks, just at the moment when they were preparing to disappear into the filmed privacy of the hotel room. Julie Delpy and Ethan Hawke then have practically the most corrosive lover’s quarrel ever filmed, in an unbroken sequence and with their real bodies—his weatherbeaten face, her breasts—very much taking center stage. By the end of the film they seem drained, exhausted, and resigned to restarting the clock by once again mixing up the tenses. Delpy’s final line says it all: “It must have been a great night we’re about to have.”