In the spring of 411 BC, the comic playwright Aristophanes presented to the citizens of Athens a new work, Thesmophoriazousae, lampooning the tragedian Euripides. The tongue-twisting title of the play means “Women Celebrating the Thesmophoria,” a reference to an annual all-female rite held in honor of the fertility goddess Demeter. The ritual setting was crucial to the plot: in the play, the women of Athens, long irritated by Euripides’ penchant for putting oversexed and murderous heroines (Phaedra, Medea) onstage, take advantage of the seclusion offered by the Demeter festival to plot their revenge. An anxious Euripides, having got wind of their scheme, persuades an elderly relative, Mnesilochus, to dress up as a woman, sneak into the rite, and spy on the proceedings. But the old man is found out, and as the play reaches its farcical climax Euripides himself appears and attempts to rescue poor Mnesilochus. (As he does so, both men quote passages from various Euripidean dramas in which heroes fly to the rescue of helpless females.) The play ends in rejoicing, as Euripides vows never again to insult the women of Athens in his work.

Ancient biographers assert that not long after Thesmophoriazousae premiered, Euripides left the city of his birth for good, having accepted an invitation by the king of Macedon, a realm occupying the remote northern wilds of the Balkan peninsula, to adorn his court as a kind of writer-in-residence. There is little reason to believe that the playwright’s abandonment of the most civilized city in Greece for a remote cultural backwater was in any way connected to the comic drubbing he had received at Aristophanes’ hands. Some scholars believe that Euripides had become disgusted by Athens’s political and moral descent during the Peloponnesian War.

And yet it is hard to resist the thought that Aristophanes’ comedy had planted a creative seed in the mind of the great tragedian. A couple of years after arriving in the Macedon, Euripides died, in his mid-seventies; the following year, in 405 BC, his final work for the stage, Bacchae (Bacchantes) was produced in Athens. At the climax of that drama—which oscillates disturbingly between black humor and deepest horror, between the city and the untamed wilds beyond—a man possessed by curiosity about what certain women are doing during the celebration of an all-female rite dresses up as a woman in order to spy on them. But this time there is no rescue, no rejoicing. At least, not for the characters: for Euripides it won a posthumous first prize at that year’s annual dramatic competition, an accolade that had so often eluded the irreligious and daringly experimental playwright during his lifetime. Within the year his great rival, Sophocles, was dead, too, and soon after tragedy itself seemed to peter out and die as well.

That Bacchae—an undisputed masterpiece, whose status as one of the greatest Greek tragedies is colored by our knowledge that it was among the last of the canonical works produced during the genre’s heyday—may well have had its origins as a bit of theatrical gamesmanship, a sophisticated tragic riposte to a comedian’s tease, seems appropriate. Few works in the history of the theater, and certainly no other work in the extant corpus of thirty-three Athenian tragedies (all that remain of the thousand or so that were performed during the fifth century BC), are as self-consciously preoccupied as this one is with the theater and its mechanisms: illusion and reality, belief and disbelief, costume and performance, laughter and terror.

And how not? It is the only surviving Greek play about Dionysus himself, the god of drama who is also the protagonist of this drama; the deity who lent his name to the festival for which all Greek tragedies were originally composed (the “City Dionysia”) and to the theater where they were performed: the Theater of Dionysus, still visible today, nestled against the southern slope of the Acropolis, its location a powerful reminder of how central the theater was to the life of the city. Euripides’ bold choice of subject, the decision to make the theater and its smilingly ambiguous god the subjects of his theater piece, allowed him, in his final play, to explore in a remarkably complex way the tensions and conflicts that had always animated his work: between civilization and nature, appearance and reality, sanity and madness, masculinity and femininity.

The plot of Bacchae recalls, in a highly literary form, an event from a dimly remembered Hellenic prehistory: the introduction of the worship of Dionysus from Asia into Greece. As dramatized by Euripides, the most overtly psychologizing of the three great tragedians, the bare anthropological fact becomes a charged personal drama. In his Prologue speech, the young god—who, we should remember, presides not only over wine and theater but over ecstatic song and dance and “liberating” madness (as his epithet eleutherios, “the Liberator,” suggests)—announces that he has come to Thebes, the hometown of his late mother, Semele, for the express purpose of forcing these Greeks to accept his worship. But the Thebans have resisted thus far, and so the deity, intent on demonstrating his power and authority, has afflicted the women with his special brand of madness, sending them running into the hills outside of town. There they have become bacchae, female celebrants of Bacchus—Dionysus’s other name—cavorting in the wild and consorting with wild animals, much to the consternation of the men who have remained home.

Advertisement

No man is more aggrieved by this lapse in civilized behavior than the young king of Thebes, Pentheus—Dionysus’s first cousin, in fact, the son of Semele’s sister, Agave, who happens to be one of the women running amok. Loudly advocating self-control, decrying what he is sure are the orgiastic practices of the new religion, determined to demonstrate his power and authority, this rigidly self-righteous young man makes his entrance announcing his intention to root out the cult. Ignoring the advice of seasoned elders who advise a more moderate path, he plans to round up the Bacchantes and to seize and punish their mysterious, strangely effeminate ringleader—who, unbeknownst to him, is Dionysus himself, masquerading as his own priest. (Just one of the play’s many instances of sly doubling and “acting.”)

Eventually the king and the god come face-to-face. Both are willful, each convinced of his own righteousness: the one ostensibly representing civilization and its concerns, as the Greeks saw it (political authority, masculinity, morality, reason, the polis), the other representing nature and its concerns (the body, sexuality, inebriation, femininity, the wild spaces outside the city). The escalating conflict between them propels this most dramatic of all Greek dramas to its awful end.

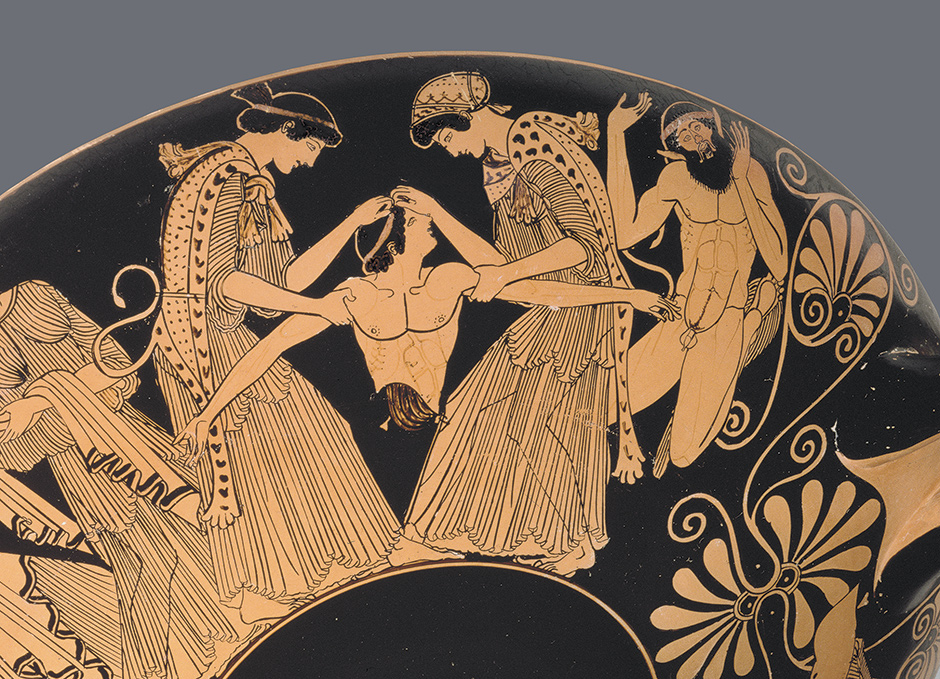

“Most dramatic,” because the vehicle of Dionysus’s climactic revenge on Pentheus is a kind of play-within-a-play, a mini-tragedy staged by Dionysus himself in which Pentheus becomes the unwitting protagonist. By this point, the arguments between the increasingly enraged Pentheus and the eerily nonchalant Dionysus have made clear to the sly immortal—and to the audience—a psychological truth of a sort we now take for granted: that the repugnance the Theban king feels for the new god’s rites and everything they represent is, in fact, fueled by a suppressed subconscious fascination. During the course of the play’s most brilliantly charged exchange, the god uses this knowledge to seduce the mortal into becoming what he had claimed to find repellent: in order to spy on the women practicing their secret rites, Dionysus smoothly explains, Pentheus must dress as a woman himself. This he finally does, and when we glimpse the once-arrogant king for the last time, having succumbed to a hallucinatory madness (he claims to see “two suns, two cities of Thebes”), he is grotesquely fitted out in drag, fussing over the folds in his skirt and worrying about his hairdo as he exits to his doom.

Or, rather, enters: for this overtly theatrical, “backstage” preparation—the costuming, the wigs, the makeup—precedes a kind of performance. When Pentheus arrives on the mountain, where his mother and the other women are celebrating the Bacchic rites, he conceals himself and spies on them—only to be discovered, exposed, and set upon by the Bacchantes, who, mistaking him in their demonic ecstasy for a lion (more double vision), tear him apart limb from limb in a grotesque parody of a Dionysiac rite known as sparagmos, the ritual dismemberment of a wild animal. It is a horribly apt punishment for the king who had so vehemently insisted on self-containment, on maintaining, as we would say today, “boundaries.”

This grotesquely staged human sacrifice makes possible both a return to reality (in the play’s famous coda, Pentheus’s mother, one of the frenzied maenads who kills him, slowly comes down from her madness and recognizes what she has done) and, more important to Dionysus, the establishment of Dionysus’s worship in Greece. In his final speech the god prophesies that Pentheus’s survivors will travel throughout Greece at the head of an Asiatic horde, knocking down the old gods’ altars and setting up new ones, including one for this young god, whose power has been so violently manifested. The play’s ending provides a colorful mythic explication for a historical fact: at some point in remote history worship of Dionysus was added to that of the other gods.

But despite the ostensible closure, a nightmarish horror lingers. As in the most awful of anxiety nightmares, the spectator has become the main attraction, the audience member forced to be an actor, religious symbolism transformed into deadly violence.

Advertisement

A great part of the thrill of the Bacchae is, then, its unusual self-reflectiveness: the “meta” quality of its reflections on how the theater works. All of us, when we attend the theater, are seeing double—seeing “two suns, two cities of Thebes.” We know we are looking at a set, at an actor; but we allow ourselves to see the setting, the character.

Still, the appeal of this extremely modern, or indeed postmodern, motif should not blind us to the play’s other great themes. One, certainly, is gender—the subject that got Euripides into trouble in the first place, in Thesmophoriazousae. In his final work, the playwright whose representations of extreme feminine emotionality had won him such notoriety decided to make two young males his leads. And yet it is their interactions with women, and their experiments with stereotypically feminine attitudes, roles, and gestures, that become the vehicle for the play’s investigation of character, desire, and mind.

In Dionysus, Euripides created a character unique in the history of tragedy. Hovering between divine majesty and human weakness, magnificence and pettiness—and between male and female—the teasing, seductive, playful, epicene god is a great study in ambiguity. Above all, it is his effeminacy—the girlish curls and womanishly delicate complexion that draw Pentheus’s attention, the odd passivity that stands in such contrast to Pentheus’s own aggressiveness—that fascinates both us and the other characters. As we know, it secretly attracts the insecure mortal; an attraction that becomes the vehicle of his destruction, as repressed desires so often do. The play’s psychological insights alone would justify its status as a masterwork.

The nature and violence of Pentheus’s destruction remind us of another great theme of the play, a very ancient one that preoccupied Euripides throughout his career, and one that his choice of Dionysus as the protagonist and of the Bacchantes themselves as the Chorus raises to a new level: religion. Bacchae is, indeed, one of the great texts about what the philosopher William James would call, twenty-three centuries after Euripides, “the varieties of religious experience.” The play shrewdly explores both the benevolent and the punishing faces of divinity: the ecstasy, beautifully conveyed in scenes depicting the Maenads at one with nature, suckling young animals and drinking milk that gushes from the earth, but also the terror, harrowingly evoked in that dreadful finale. Both elements are consummately summed up in the ambiguous Dionysus himself.

Not the least of the means by which Euripides conveys the swift shifts in mood associated with the mercurial god is the play’s remarkable poetry. Commentators on the play have long admired its extravagantly colored choral lyrics, whose unusual density, intricacy, and power stand in stark contrast to the plainspoken, quotidian language the playwright uses for his dialogue—a conventional contrast that here pointedly echoes this work’s overarching tensions between the sacred and the secular, between the heightened consciousness of religious revelation and the coolly marmoreal contours of rationalism. The intellectualism makes itself felt in the terse, gnomic language of the characters’ exchanges with each other. (“That makes no sense,” a confused Pentheus sputters when faced with Dionysus’s shape-shifting. “Sense is nonsense to a fool” comes the famous retort from the god.)

The ecstasy is exemplified by the chorus the Maenads sing at the fateful moment when Pentheus finally succumbs to Dionysus’s teasing and agrees to dress up as a woman—his last moment onstage, in fact. This is the true climax of the play, and it is marked by verse in which the Chorus, eager to dance in triumph over their stubborn adversary, compares its joyful movements to those of a fawn that has escaped the hunter. These famous lines’ swiftness and dappled coloration, the breathless alterations between light and dark, density and clarity, simile and metaphor, comparandum and comparatum convey the sense of swift movement through a shaded wood:

Shall I toss my head and skip through the open fields

as a fawn slipped free of the hunt and the hunters,

leaping their nets, outrunning their hounds?

She runs like a gale runs over the plain

near the river, each bound

and plunge like a gust of joy, taking her

dancing, deep through the forest

where no one can find her, and the dark

is free and its heart is the darkest green.

Such lyrics—quoted here in Robin Robertson’s limpid new translation—remind us why Euripides’ songs were so highly prized in antiquity—and not just by his Athenian audience. The historian Plutarch relates that, during the Peloponnesian War, Athenian prisoners of war laboring in the mines in Sicily would sing the playwright’s lyrics in return for better treatment from their masters.

The strong presence of the Chorus in this play is, in fact, a self-conscious gesture on the playwright’s part that unites Bacchae’s two dominant preoccupations: theater and religion. Euripides and his audiences were bound to be aware that tragedy had its origin in a Dionysiac rite that was accompanied by a particular kind of choral song called the dithyramb, which was sung by choruses of fifty men and boys in celebration of the bizarre birth of the god. (When the pregnant Semele was burned by Zeus’s fire, the king of the gods sewed the unborn fetus into his thigh until it could grow to full term: a story derided by the atheistic Pentheus in the play, to his cost.) Aristotle, writing a century after tragedy’s heyday, indicates in his Poetics that drama began when the leader of the dithyrambic chorus stood apart from the rest of the group and began to sing back to them—the origin of the oppositional stance, the dialogic structure, that allowed tragedy to embody conflict, rather than merely describe it.

By the time Euripides was an old man, he (like us today, often) seemed to be increasingly embarrassed by the Chorus, relegating it to a perfunctory role in some of his later plays. But in his final work—inspired, as some scholars think, by the stark, numinous magnificence of the wild Macedonian surroundings where he sought refuge from the madness of Athenian politics—he restored the Chorus to its central position, making it as vital a character as it had been a hundred years earlier, when tragedy itself was in its infancy.

Like so much else about Bacchae, a work that is at once alarmingly primitive and enormously sophisticated, elemental and complex, the famously “archaizing” prominence of the Chorus adds to our sense that this is the ultimate, the compleat tragedy—a genre that, in its end, found its beginnings once again. Like the god it both celebrates and abhors, a god of both growth and decay, of beauty and terror, the play embodies ostensibly incompatible contradictions. All too conscious that it stood at the end of great tradition, it also seems aware of the possibility of perennial revival and rebirth—a possibility borne out by a line of translations and adaptations that goes back centuries. But then, Bacchae knows well that we must expect the improbable. As the Chorus sings in its final song, while the ruined body is being borne away and the survivors turn to the difficult business of living, “What we look for does not happen;/what we least expect is fashioned by the gods.”

This Issue

September 25, 2014

The Cult of Jeff Koons

Obama & the Coming Election

Failure in Gaza