“Why are you telling me this?” A friend often poses this dry and disconcerting question to the stories, fictional and otherwise, that come her way. Of all the reasons someone may tell a story—and there are many more than Cicero’s famous three, “to teach, to please, to move”—surely the most demanding on the art of fiction is the reason of inner compulsion. The felt personal necessity to tell a story is of course likely to be part of the motive of every storyteller; but it is another matter when it becomes the dominant, or sole, reason.

When a writer has only an incidental relation to the reader but is instead shaping a story entirely in answer to personal need, and so is in effect talking to himself, the odds are against the results succeeding; and the writers we admire who have written chiefly from this inner compulsion, among whom I would include Kafka, Melville, and—in poetry—Dickinson, are extraordinary in part because they are able to carry off the nearly impossible. It is a little like someone at the breakfast table telling you her dreams. From Emily or Franz, I maybe could bear it; perhaps not so much from most others.

That the Scottish writer A.L. Kennedy, very much an inner-compulsion writer, succeeds at all, then, is something of a miracle and a sign of her brilliance; but that only parts of her fiction manage the leap from the interior self to the world of readers is certainly not surprising. The inner necessity of the writer translates to the interest of the reader only with great art. And what very odd, idiosyncratic things Kennedy has been writing for the last twenty years, novels and short stories that have been widely praised in Britain and, more locally, here. Most recently Kennedy has published the elaborate novel The Blue Book, and this year, the collection of stories All the Rage.

Original Bliss (1997), her first novel to appear in in the US, centers on the entanglement of an abused housewife with a faith healer and includes a nearly clinical, and antierotic, exploration of addiction to hard-core porn. In the last decade Kennedy’s most impressive novel was Day, an even more complex tale, set in Germany in the late 1940s. A former RAF gunner has taken a job as an extra in a British-made feature film set in the same stalag where he was imprisoned at the end of the war. His mind is layered with memories of the war and of his childhood; the story line flickers through many times and places.

As striking as Kennedy’s subject matter often is—embracing violent sexuality, traumatic memories, extravagant con artistry, and minutely calibrated power politics on both public and domestic stages, almost always from a male point of view—it is in her manner of storytelling that Kennedy’s true idiosyncrasy lies. By virtue of a double-focus practice of subjective narration, which admixes close third person with first-person interior monologue (and sometimes even second person, as well), she creates a consistently claustrophobic sense of her characters. Here, the main character of Day (Alfred Day) is brooding on his grievances and fears while talking with Vasyl, another extra on the film shoot whom Alfred suspects was an SS snoop in the war:

Alfred let the silence lap out between them and liked that his hands felt restless and his spine alert.

Took me a long while, cocker, but I learned how to fight in the end and slow learning is deep, the best kind, and we didn’t quite finish our business together, did we?

Vasyl was still unsteadied and rushing in to fill the pause. “You know, I have thought that I might actually want to buy that…that old pistol from you. I have some money—not much. English pounds.”

You don’t want to buy a bloody thing. You want that little knife of yours stuck in me—aerate my ribs….

That this menacing scene does not, in fact, culminate in outright violence is also typical of Kennedy—violence is usually veiled or recalled, while in the “present” tense of the novel, many such unfinished encounters accumulate, leaving us in long-standing doubt about Alfred’s sanity, Vasyl’s intentions, and whether or not the remembered events of the past actually occurred. And while this can certainly make for suspense, when our knowledge of some basic facts is suspended for long enough—in Day, for a good two thirds of the book—our confidence in the narrative can flag. Everything depends on our willingness to walk in confusion and fear with the divided Alfred, always uttering one thing aloud and saying something a lot (or just a little) more intense to himself. Sometimes, not always, he addresses himself as “you”—the second person functioning as first person—as here, remembering a scene with his mother, when he had first enlisted:

Advertisement

His mother lost herself for a while in little cries that seemed to leave her frightened, woman’s sounds, and her hands fluttered and tried to shield her head and he went around the table and held her, the twitch and flicker of pain in her, and he touched her hair.

Didn’t pray for her, though, did you? Only for yourself. You asked if God could make you strong.

In a more straightforward and comic use of the device, the central character of the short story “Because It’s a Wednesday” (in the new collection All the Rage) offers snarky asides to his actions. As it begins:

Because it’s a Wednesday, he’s shagging Carmen.

Grotesquely unlikely name for a cleaning woman, Carmen. It doesn’t even suit her as a person, in fact—entirely inappropriate, in fact. As is the shagging, of course.

Kennedy is not the only contemporary writer to use such a device (close third person alternating with interior monologue), which is an estimable inheritance from the modernists; but she uses it so consistently that it seems not just a device but a tic, and then eventually appears to be something larger. It is as if, as we read, we are actively prevented from resting in the narrative—instead, we are always listening for the disruptive, not-quite-repressed voice below the surface, muttering dark truths. (Musically, the effect is antiphonal; and it strikes me that a vocal setting of one of Kennedy’s stories would make a wonderfully mad choral piece, rather like the mannered misfire of Eugene O’Neill’s Strange Interlude.)

The device gets even more intense when a notional “reader” is dragged into the mix; when, as in The Blue Book, the reader is addressed as “you” from the beginning, by an insinuating but invisible narrator, while the main story being told concerns Derek (a con artist posing as a mentalist and seer) and Elizabeth (his partner and shill), both of them handled in close third person with both their interior thoughts sprinkled throughout as italicized monologues. The following passage begins with an address to you, the reader. Derek’s inner thought appears at the end:

And you can rest assured that you’re more honest than most people.

Which means you’d prefer to be careful about your employment and it could only seem strange to you, quite terrible, if you slipped into earning your living by doing wrong.

You wouldn’t choose to be associated with an unethical company, or criminal behaviour, deception.

So you wouldn’t do this….

But your book has to show you the man who would….

He [Derek] is not an accidental man. He is prepared. He is never, if he can avoid it, outside in the day—night walks at home and sunscreen with the homburg when he’s on the road. No red meat, not ever—rarely meat in any form—a diet he constrains to thin essentials, minimums, as poor in iron as can be survivable. The anaemia refines him, tunes him, lets him flare.

Because appearances matter. Everyone judges the cover before the book.

Apart from wishing that Derek, along with other Kennedy characters, did not so often speak to themselves in clichés—which the author obviously finds funny but which may reveal a too-easy contempt—it should be obvious how high-wire this fictional game is and how many things can tumble down, including us the readers.

Sometimes, reading Kennedy, I wished that she would allow herself, as the narrator, occasions in which she could pry herself loose from the claustrophobia of one of her creatures long enough to describe the room he stands in. (Or, in the case of The Blue Book, the ocean liner.) No one wants a travelogue, but a little physical scenery, or a prop, even just a glass of water on a table, would be welcome. The most extended passage of such description in The Blue Book appears in an early chapter:

Outside Beth’s cabin, passengers stagger and shoulder walls as the ship bounces, shrugs. There are little impacts and the blurred melodies of hearty chat, or sympathy, or good mornings. And the staff will smile, because this is compulsory and they will polish and dust and varnish and paint unendingly, because this is also required and the seafaring way—otherwise chaos would triumph, water and hard weather would eat the ship.

Even this helpful passage offers a setting from a highly subjective, slightly off-kilter view, from the point of view of a woman who is struggling with seasickness along with much bigger psychological problems. It is wonderful writing, of course—Kennedy’s wittily paced sentences accumulate like so many coins tossed from the emperor’s coach. But this novel, like all her fictions, would benefit from many more such moments depicting the physical world, providing just enough detail for readers to envision the stage on which her dramas are enacted.

Advertisement

It may be that for this writer the only real “things” in the world are thoughts and feelings; that the landscape of the psyche is sufficient; and that the internal, conflicting and overlapping, impulses of two people waiting in a queue (as in the story “Late in Life,” from All the Rage) are action enough. From that story:

He’s quite frequently secretive. They have decided to like this about him. His love of hiding has nothing to do with her and should not be a worry—it dates from much earlier situations which were unpleasant. They agree that his varieties of absence are okay and usually endearing.

He nudges against her side, “Shush.” This is a suggestion that she should hide, too.

I have wondered, in the course of reading Kennedy, about the possible differences between the British temperament and ours; is there something about the contemporary culture of the British Isles that keenly hungers for these minute nuances of motive and attitude? It did occur to me that the age-old habits of British reticence may incline readers today to relish Kennedy’s habitual lifting of the public mask to reveal darker thoughts within—as in the characteristically British genre of the detective story. Many of Kennedy’s tales do unfold almost in the detective story manner—and if there is one large charge I would lay against her work, it is her tendency to use a big “reveal” as a climax. A story from All the Rage, “Baby Blue,” serves as a case in point.

Here the narrator, a woman, tells the story of her having “got lost” and wandered into a sex shop. Her bewilderment, disgust, and fascination with the items she finds on display accumulate into a comic set piece. A shop assistant’s query is indicated in boldface:

For yourself?—and I had no answer. I’d halted in front of a bank of what were probably—definitely, now that I looked—fake vaginas and I couldn’t answer—who would?—that, no, I intended to buy such a thing for someone else. Who? For whom? A female friend to whom I would suggest that her own was unhelpful? Or would I give one to a straight man as if he’d no chance of access to a real one?… Or would I foist one on a gay man? As what, a novelty letter box?…

Chocolate-flavoured condoms. They had chocolate-flavoured condoms.

You like penises, you like chocolate, why not both?

There were many whys for not both. For many reasons, my opinion was in favour of not both.

If I like penises, might I not be assumed to hope the flavour of a penis will be penis, which is to say not too much of a flavour, ideally just this subtle, unflavoured pleasantness and that isn’t a problem, how could that be a problem? I don’t feel my experience of oral sex is intended to be primarily culinary.

Unless is it? Have I got this wrong? Is it not about love, about knowing and being known? Is it—I can get confused—perfectly reasonable in that, or any other, context to insist, to appear to insist, to act in such a way that I’d be insisting your penis is inadequate and ought at least to taste of chocolate to compensate, so here you go and roll on one of these?

I love the voice Kennedy has adopted here, the reasonable (if naive) everywoman in the face of our ghastly sexual culture. We know, from the outset of the story, that the narrator has blundered in among the dildos because she has been distressed by a visit to the doctor. Alas, by the end of the story the “twist” is revealed. The narrator has been told by her doctor that she needs to have a hysterectomy.

In fiction, this can only be called a cheap trick. Imagine what a better story this would have been if we had known about the narrator’s impending loss from the beginning; that knowledge would have still allowed us to laugh, but it would have been a deeper laughter and it would not have left us feeling gulled. Such a maneuver—and it occurs widely in Kennedy’s work, very often in the late revelation of a character’s abuse as a child—seems intended to shame readers, to place a grievance at our feet. But it may not be so designed after all. It may, curiously, stem from the solipsism alluded to earlier; if the writer is in essence talking to herself, she already knows what her stories mean; so the belated tacking-on of information, as a device of “suspense,” seems like an afterthought—“Oh, yes, I must remember that there is a reader! I will tease and surprise her!”

Whatever the case, it is to be hoped that Kennedy in the future will rely on her great gifts of nuanced insight, humor, and nimble prose and may not find it so necessary to confuse or dupe us in the interest of “suspense.” One of her most remarkable books, in fact, is not fiction at all—it is called On Bullfighting, and was written in the late 1990s.

At roughly 165 pages (including glossary), this longish monograph sets its background and difficulties squarely before us. Right from the start, Kennedy tells us that the occasion for her research into the bloody Spanish corrida is twofold. She has been asked (presumably by an editor) to write about bullfighting; and she is at a grim moment in her life—depressed to the point of attempting suicide, in extreme pain from a slipped disk, unable to write. The collision of subject matters—of an ancient, cruel, mystical rite with her personal trouble—leads her to research and write an extraordinary treatise, a meditation on the human confrontation with mortality. Further information about the writer’s suffering emerges as we go along, but nothing seems to have been withheld for effect. Moreover, Kennedy’s extensive, patient descriptions of the bulls, the matadors’ maneuvers, and the crowds place us fully in the world being explored.

Naturally, she is distressed by the bull’s suffering, his bewilderment and fear, the methodical wounding he endures—first from the banderilleros’ darts, then from the picadors’ lances that pierce the muscles of his shoulders and neck so that his head is lowered (and somewhat less lethal) by the time the matador encounters him. But she sets aside her initial reactions of outrage against the corrida in the service of her task, which she describes as “to pay the best of my attention, to try to know, to understand.” By explaining how bulls actually see—with monocular vision, the eyes set on each side of the head—Kennedy shows us how the business of playing the bull with a cape actually works:

Running forwards tones down the visual input from the background and heightens their perception of the errant target. It would also explain why a man standing still, unless he’s directly in the bull’s path, can be safe—he’ll simply fit in with the general, less stimulating, drift of the landscape. And if you consider that movements going towards the nose of the bull—against the usual flow—are something immensely stimulating, it suddenly makes sense that the pase natural, a cape pass which moves the cloth across the toro’s leading eye in a noseward direction, is regarded as the pass upon which all toreo is founded and is the pass which always lures the bull forward for the final sword thrust.

That is only a small part of the careful analysis Kennedy offers near the beginning of the book; later, when she is showing us the action of the ring, our tutorial in optics and choreography pays off:

With the muleta [the small cape on a rod used in the final phase of the bullfight], Rodríguez [a matador] takes risks, the bull almost catching him several times, while the plaza seems to contract around him and his work. Then, while he attempts a chest-high pass—a pase de pecho—to the right, his feet catch against each other, delay his retreat for just too long. And, directly in front of me, perhaps thirty yards away, I see a man’s body jerked and hoisted into the air, shaken and bounced above a massive, implacably animal head while his limbs flap and turn against his will. His noiseless cry looks like a smile.

Kennedy describes at least a dozen such encounters in the ring; the book culminates with an account of a day in Seville observing the very young—in 1999, he was only seventeen—superstar of bullfighting, the matador “El Juli”:

The toro…stalls in the midst of charges and hooks its head. Time and again it seems that “El Juli” will be caught, but still he nudges closer and closer to the bull with successions of faultlessly linked tandas [groups of passes], threading in left-handed naturales and chest passes which prepare the bull for its final lunge. Now and again there are cries of astonishment, hisses of alarmed breath, but otherwise the plaza is silent.

Never would I have guessed that I would become so fascinated, and implicated, in a spectacle that I have in my travels gone out of my way to avoid. Without in any way dismissing the obvious ethical objections to an activity that dates back at least as far as the Minoans, and made all the bloodier in the Roman Colosseum, Kennedy has made me understand something about the spiritual possibilities of an ancient rite.

That she also, in the course of writing this book, wrote her way out of a writer’s block is only of incidental interest. But surely one of the reasons she was able to do so is owing to her eager, evident consideration of the readers she addresses. In On Bullfighting, Kennedy manages all of the traditional tasks—to teach, to please, to move—with plenty of room left over for her own duende.

This Issue

September 25, 2014

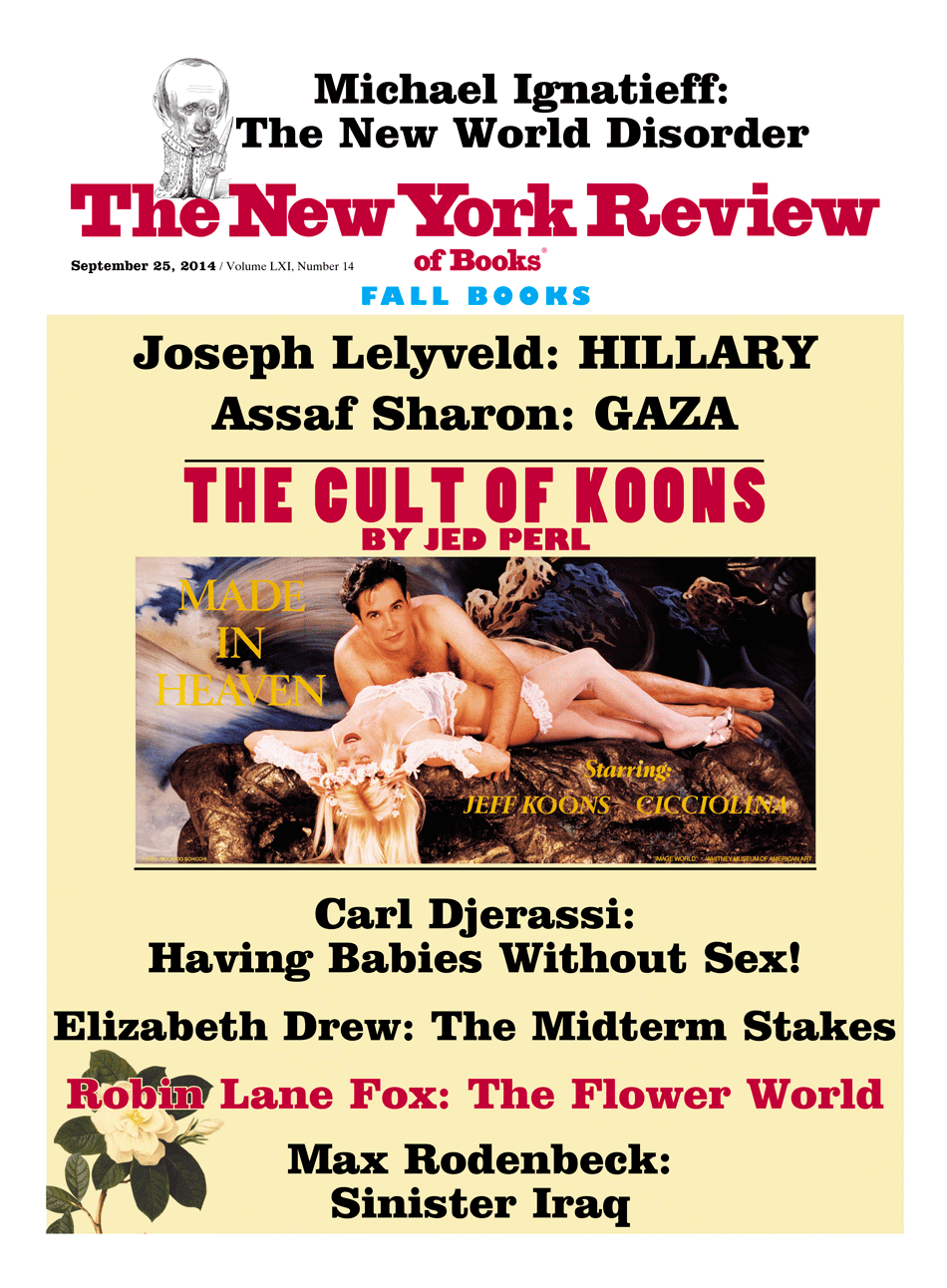

The Cult of Jeff Koons

Obama & the Coming Election

Failure in Gaza