In the summer of 1969, as the violence intensified in Northern Ireland, the poet Seamus Heaney was in Madrid. Like any tourist, he went to the Prado, but not specifically, he later said, “to study examples of art in a time of violence.” He found, nonetheless, that some of Francisco Goya’s work on display “had the force of terrible events…. All that dread got mixed in with the slightly panicked, slightly exhilarated mood of the summer as things came to a head in Derry and Belfast.” He found Goya’s work “overwhelming,” and was fascinated at the idea of an artist confronting political violence “head-on.” In his poem “Summer 1969,” he wrote of his time in the heat of the Spanish city while Belfast burned:

I retreated to the cool of the Prado.

Goya’s “Shootings of the Third of May”

Covered a wall—the thrown-up arms

And spasm of the rebel, the helmeted

And knapsacked military, the efficient

Rake of the fusillade.

Heaney ended the poem with an image of Goya at work:

He painted with his fists and elbows, flourished

The stained cape of his heart as history charged.

There are two ways, perhaps, of looking at Goya, who was born near Zaragoza in 1746 and died in exile in France in 1828. In the first version, he was almost innocent, a serious and ambitious artist interested in mortality and beauty, but also playful and mischievous, until politics and history darkened his imagination. In this version, “history charged,” took him by surprise, and deepened his talent. In the second version, it is as though a war was going on within Goya’s psyche from the very start. While interested in many subjects, he was ready for violence and chaos, so that even if the war between French and Spanish forces between 1808 and 1814 and the insurrection in Madrid in 1808 had not happened, he would have found some other source and inspiration for the dark and violent images he needed to create. His imagination was ripe for horror.

The retrospective of Goya’s work at the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston moves carefully, gingerly, and creatively between these two positions, making some ingenious connections and juxtapositions along the way, and also a few that are, almost by necessity, awkward and odd. There is no perfect way of presenting the work of Goya in all its variety and ambiguity.

In the first room of the exhibition, devoted to self-portraits and works in which the artist himself appears, clues are given about the complexity of Goya’s nature. There is the small Self-Portrait While Painting from around 1795, in which he is half-silhouetted in front of a wall of whiteness that is painted with loose and open brushwork. This is not sunlight, nor could its brightness come from artificial light. More than anything, it looks like paint itself applied with pleasure and ease. Faced with a choice between a detailed depiction of a world beyond the window or sheer luminosity, Goya went for what would most delight and surprise the eye.

The whiteness allows the viewer to pay more attention to Goya himself, his face and his costume, and the table to his right done in quick strokes of turquoise with very precisely painted writing materials on it. There is a palette with paint in Goya’s left hand. Dressed in a short bullfighter’s jacket with stripes of richly embroidered red down the side and at waist-level, he stares at us and, we presume, at his sitter. Although his costume makes him appear the painter as performer, his face has nothing of the actor about it; he is almost comically ordinary as he sets about his work. His button nose lacks appeal. His hat, which has candleholders embedded in it, is too large. It is clear from the composition that he has no time for dullness. As you look at the eyes, the frank and pitying gaze, you get an effect that is quietly unsettling and disturbing.

Close by is a self-portrait made twenty years later, when Goya was almost seventy. There is now a great tired guardedness and sadness in the face; the expression is raw, unchallenging, suggesting a vast vulnerability with much kept in reserve; there are no illusions or self-delusions. While this painting is filled with inwardness, it is also a hushed proclamation of selfhood. The redness of the lower lip, for example, offers a hint of sensuality and energy.

Despite illness, deafness (he was functionally deaf from 1793 when he was forty-six), and loss (all but one of his children died soon after birth), he will keep working, producing, for example, the great late lithographs of bull-fighting in Bordeaux, and completing another sombre self-portrait at the end of his life that hangs in the final room of the show, a portrait that has elements of a Pietà, in which the stricken Goya, his left hand gripping the sheet in pain, is held in the tender arms of his doctor, with ghostly figures behind them. Goya’s instinct for theatricality, so apparent in the self-portrait made in the studio, returns now as an image of dark and unsparing self-exposure. Not only is he unafraid to show himself in such distress, but it seems as if this and the other two self-portraits are an essential part of his aims as an artist—to do his best, when he was allowed, to make sure that pictorial space was rich with excitement, insight, incident, painterly energy, surprise.

Advertisement

In the room between the two self-portraits there is a large bravura portrait of the family and servants of the Infante Don Luis, done in 1784, when Goya was making his name as a court painter in Madrid. Although there is a single candle on the table, there is no illusion created that this is the source of light for the painting, which comes evenly from where the viewer looks. Goya himself appears at the left, in homage to the Velázquez of Las Meninas (of which he had made an etching), but there is no real sense that he was painting the sitters from that position, or that they had ever, in fact, gathered to be painted as they appear here. Most of the thirteen figures seem oddly alone, sketched or painted singly or in small groups and then assembled artificially in the painting. Except for the hairdresser of the infante’s wife who is carefully arranging her hair, they seem eerily unaware of one another’s presence.

We sense their mortality, carnality, and frailty rather than their majesty or power. This is most striking in the depiction of the infante himself. Painted in profile, he is aging, in sharp and dramatic contrast to his young son, who stands behind him and, also in profile, has the same face, except young and innocent and tender, the same distant stillness. The infante is also in contrast to his wife, who appears bigger, more alert and alive than he is. As the eye moves among all three, it is the infante’s melancholy distance from things that becomes most apparent. His stare is disembodied but it is not vacant; it is filled with knowledge and sadness. When Goya made the painting, the infante was out of favor with his brother the king, but the sense of loss, or reduced power here, is not worldly; it could not be restored easily; it has come from time, from the experience of life itself, and the experience of time passing. It has come from within. His face and his pose have the same unsettling edge as Goya’s own self-portrait in old age.

The ink drawing and the etching with aquatint in the same room—two fiercely graphic versions of Goya having nightmares—are from the second half of the 1790s, when he was in his fifties. In their stark sense of conflict and readiness to deal openly and dramatically with demons, they almost require a context; it is possible that they would look better among other works by Goya, works that seem to relish darkness and enjoy creating unsparing imagery, and use the cuts of the etching with immense, almost cruel skill against the softer, shadowy, haunting tones of the aquatint.

In the next room, the formal painting, done in 1788, of a child—Manuel Osorio Manrique de Zuñiga—dressed in red with a wonderfully painted white sash would be a picture of doll-like innocence were it not for the magpie that the child has on a string. The bird is being watched by one mild-looking cat and glared at by another, more rapacious-looking feline that will, it seems, eat the bird alive, and soon. There is a black cat behind the other two. The yellow in the hungrier cat’s eyes is matched by the yellow of some goldfinches, painted with great precision, in a cage to the right; the red in their beaks also matches the red of the boy’s one-piece costume.

Light comes from the right of the painting above the cage; it appears as a gray-green glow and then as greenish shadow, leading to darkness on the left of the painting above the cats, becoming a sandy yellow at the boy’s feet and then a shadowy brown at the very front of the painting. The drama within this picture arises from an image of innocence and the sense of a great still artificiality that the boy exudes appearing to dominate the space and then slowly being undermined not only by the birds and the cats, but also by the background colors, which are ambiguous, uneasy, and almost ominous.

Advertisement

Directly facing this painting, down a long gallery, is a work done more than twenty years later called Time. It shows two ravaged old women with Time the Reaper leaning over them with long delicate wings and, behind to the left, what looks look a doorway of glowing yellow light. The women are overdressed, with makeup and dyed hair, and painted with grotesque cruelty and strange mischief. Goya clearly took pleasure in the sickly shock of the image he was making.

One of the women is wearing a diaphanous white dress with elaborate work around the shoulders and bodice; her hair is dyed a light orange. She has rheumy eyes and hardly any mouth at all, or teeth. Her friend dressed in black is almost more gruesome. Goya catches these two old ladies in all their ludicrous vanity. They will, the painting suggests, not be missed when time takes them to a place where they will be spared the consequences of their own illusions. What they will leave behind is a sense of wonder about the figure who painted them, who kept this painting with him all his life, whose relish for images of horror and decay is slowly becoming more apparent.

This relish is on display in the series of etchings and aquatints called Caprichos, done between 1797 and 1799. If there are versions of love and innocence here, they come as sheer excitement and hilarious satire on what many others hold dear, as in Can’t Anyone Untie Us?, in which a distressed young woman and man seem to have been soldered into each other at the waist, with a thorny tree behind them, and a huge owl on their shoulders with its wings outspread. There is also an etching of a donkey reading the alphabet in the pose of a pupil.

There is a vicious-looking mother slapping a child’s bare behind with a shoe, holding up his shirt by her teeth. There is another work from this series called Until Death, in which an old crone filled with vanity looks in the mirror while two men snigger, and another in which an old crone is, it seems, praying, but she has a deeply malevolent look on her face. These works have all the signs of having been made by Goya to amuse himself as much as others, and created perhaps to atone for the bucolic cartoons he had to make for court tapestries and the respectful portraits of the powerful he had to do for money.

The painting of the diseased old crones hangs in the same room as portraits of posh children, thus offering a juxtaposition of age and youth, decay and innocence. The problem is that the room includes, as an example of an image of aging, Goya’s portrait of María Antonia Gonzaga, Marchioness of Villafranca, done in 1795. She was a sixty-year-old widow, mother-in-law of the Duchess of Alba. This is not merely one of Goya’s best paintings of a person no longer young, it is simply one of his best paintings, and it needs a more neutral setting than a wall between an innocent boy in red and the two gruesome old women. María Antonia emerges here as a figure of fashion—her white shawl is painted in sumptuous and delicate detail, as is her dark dress with dark blue stripes and the blue rosette in her hair and the rose with blue ribbons on her chest. Her rings and a single long earring catch the light.

What is captured more than her age, or her clothes and jewelry, is a sense of an inner life, the sort of guardedness that Goya displayed in his own late self-portrait, which implied rich experience and deep intelligence. This guardedness is combined with a dark gaze that is alert and an expression that is almost sardonic.

The brushwork becomes more intense and delightful as it moves from her hands up through the brilliant and decorated shawl toward her face. The eye of the viewer keeps moving upward toward María Antonia’s eyes, savoring the way age has enriched her spirit. Her pose is formal. She is a figure of power. Her shock of frizzled hair is wild against the calm wisdom and deep intelligence in her face.

This portrait, then, is not an example of aging; it is not an example of anything. It has its own particular living force. It would be marvelous to see it beside Goya’s portrait, painted in the same year, of the marchioness’s son, José Álvarez de Toledo y Gonzaga, the husband of the Duchess of Alba, which hangs a few rooms away in the long room devoted to portraits. This, too, displays a powerful figure posing for the painter, and it also suggests someone engaged, engaging, almost sexual. He appears here as a serious and complex man. He has an air of irony or even arrogance in his gaze that makes you want to go back to look at his mother’s face again to see if she too has signs of that same aura.

The complexity Goya offers the marchioness and her son is not obvious in all of the portraits. Some are merely about power, and often the clothes are more interesting and oddly alive than the faces. But it would be too easy to say that Goya put his best energy into work not done for patrons. The portrait of the actress Antonia Zárate y Aguirre from around 1805, for example, which normally hangs in the National Gallery of Ireland, is vivid and brilliant. Antonia wears a black mantilla and a black dress, with long white fingerless gloves; she has black eyes and black hair. Offering her a placidity and an allure, the portrait, like those of the mother and son, suggests a rich inner life. But there is also a feeling that Antonia is in control of how she looks here, that her stately dignity has been managed with care by the sitter herself rather than by the painter.

Like the painting of the marchioness, part of the power of this portrait comes from the lack of distracting details in the background. Antonia sits on an energetically painted yellow sofa; the yellow is lit equally on both sides of her. Both the openness and virtuosity of the brushwork and the variety in the brown on the wall behind the sitter pull in the light and make the black clothing and hair and eyes immensely rich and deep, and the flesh tones exquisite and tender.

While some of the paintings and etchings in the room before the large room of portraits suggest chaos and violence and indeed hysteria, it is clear that the curators have been clever and careful about holding back Goya’s war paintings until just after the display of portraits, which are so filled with stability. In a few steps, you move from worldliness, order, control, beauty, and privilege to lunacy and to history as a nightmare from which Goya and the people he depicts cannot awake. The title of the show—“Order and Disorder”—in the juxtaposition between these two rooms becomes apt and challenging.

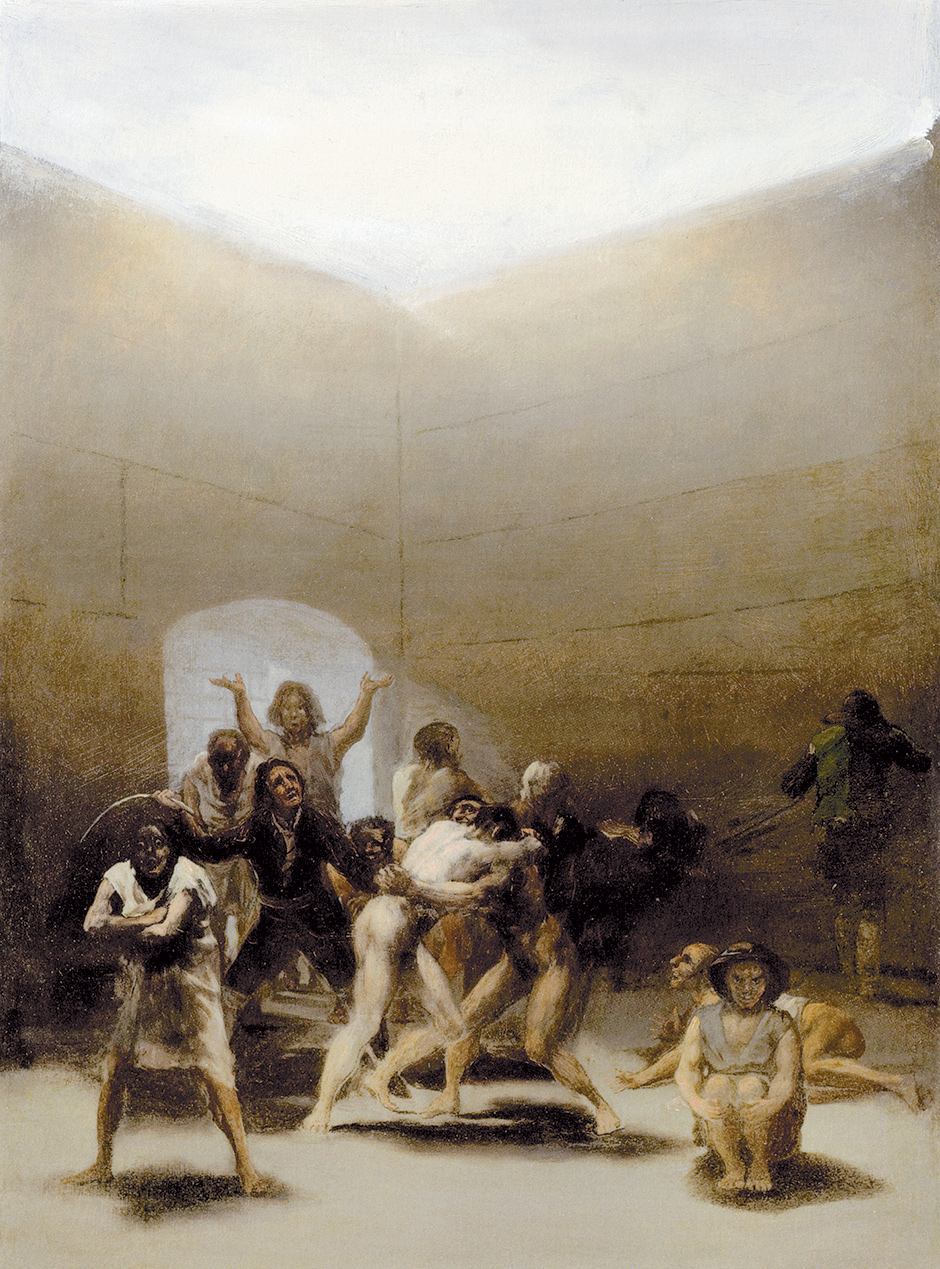

Yard with Madmen, from 1794, has echoes of the earlier painting of the infante and his family. All of the madmen, under floating white light, seem mad in a lonely and personal way. Only the two men at the center locked in a wrestling match seem to recognize one another. The sense of isolation, which had elements of the comic or the awkward in the royal painting, now is deeply frightening and disturbing. While this seems like a sort of failure in the royal painting, now it appears to be richly and consciously composed, superbly managed for maximum drama and visual shock.

The show in Boston does not include the two famous paintings of the events of the Second and Third of May 1808, which Seamus Heaney wrote about in his poem, but rather has a smaller work called Attack on a Military Camp, done between 1808 and 1810. This shocking painting shows dead and dying figures to the left, while on the right a group of soldiers have rifles directed at them, and in the middle there is a woman with a child, and she is fleeing from the rifles. Almost everything is designed to focus attention on her eyes in the act of looking backward in great terror.

Close by this painting, on one single wall, are twelve prints from Goya’s series of eighty etching and aquatints, Disasters of War, done between 1810 and 1820, in the aftermath of what became known as the Peninsular War. Some of the fighting took place in the streets of Madrid, and included executions of Spanish insurgents and civilians, some of them occurring close to where Goya lived. The fighting was followed by famine.

These etchings have a great starkness. The man hanging from a low tree, for example, has a fierce dignity. In the distance, like shadows, are two other figures hanging. The cuts of the needle to make the etching seem to add to the graphic human drama of this moment. And then to the right in this etching there is a French soldier relaxing, chillingly amused by it all. In another etching, called The Consequences, nightmare birds, in the same poses as the ones who haunted Goya’s dreams, now feast on a dead body. In another, three simple lines to the right signify the barrels of rifles; we don’t see the soldiers at all, so that the blindfolded figure tied to a stake with his head bowed is all the more central and exposed. In the distance there are other figures being executed, and soldiers ready to fire.

The problem with the exhibition is how to follow this set of unforgettable and haunting images. Goya, of course, made other work, including peaceful still lifes, in the years when he made these etchings. The war etchings may be the culmination of one aspect of his talent, but his talent came in many guises. In the last room there are images of mirth as well as ghostly images, thus emphasizing how difficult it is to reduce the breadth of Goya’s vision.

It is hard, then, to view the large picture on the very last wall as a final statement, or anything like one, despite the claim on the wall text beside it that Goya had a “prediliction to tie up loose ends.” It is a painting of an old saint receiving communion, and it has too much bloated and rhetorical religiosity to be placed in such a prominent position.

While Goya made religious paintings, he did not do so with the same passion and originality that we see in his secular work. His John the Baptist, for example, looking like a handsome Spanish youth, all thigh and torso, seems created to beguile the unconverted as much as baptize them. It might have made more sense to have placed the portrait of the Duchess of Alba, filled with youthful energy and earthly beauty, which normally is in the Hispanic Society of America in New York, and which hangs in Boston in the room filled with portraits, on that last wall instead of the religious image. She would at least have made clear that Goya’s interest in this world exceeded his interest in the one to come. It would have emphasized too that in a time of trouble this troubled spirit stood up for life in all its variety—its beauty and its loose ends as much as its lunacy and cruelty—and he recreated the wonders of the flesh as much as he did the world’s horror.

This Issue

December 18, 2014

You Can’t Catch Picasso

How He and His Cronies Stole Russia