For twenty years now, the Western politicians, journalists, businessmen, and academics who observe and describe the post-Soviet evolution of Russia have almost all followed the same narrative. We begin with the assumption that the Soviet Union ended in 1991, when Mikhail Gorbachev handed over power to Boris Yeltsin and Russia, Ukraine, and the rest of the Soviet republics became independent states. We continue with an account of the early 1990s, an era of “reform,” when some Russian leaders tried to create a democratic political system and a liberal capitalist economy. We follow the trials and tribulations of the reformers, analyze the attempts at privatization, discuss the ebb and flow of political parties and the growth and decline of an independent media.

Mostly we agree that those reforms failed, and sometimes we blame ourselves for those failures: we gave the wrong advice, we sent naive Harvard economists who should have known better, we didn’t have a Marshall Plan. Sometimes we blame the Russians: the economists didn’t follow our advice, the public was apathetic, President Yeltsin was indecisive, then drunk, then ill. Sometimes we hope that reforms will return, as many believed they might during the short reign of President Dmitry Medvedev.

Whatever their conclusion, almost all of these analysts seek an explanation in the reform process itself, asking whether it was effective, or whether it was flawed, or whether it could have been designed differently. But what if it never mattered at all? What if it made no difference which mistakes were made, which privatization plans were sidetracked, which piece of advice was not followed? What if “reform” was never the most important story of the past twenty years in Russia at all?

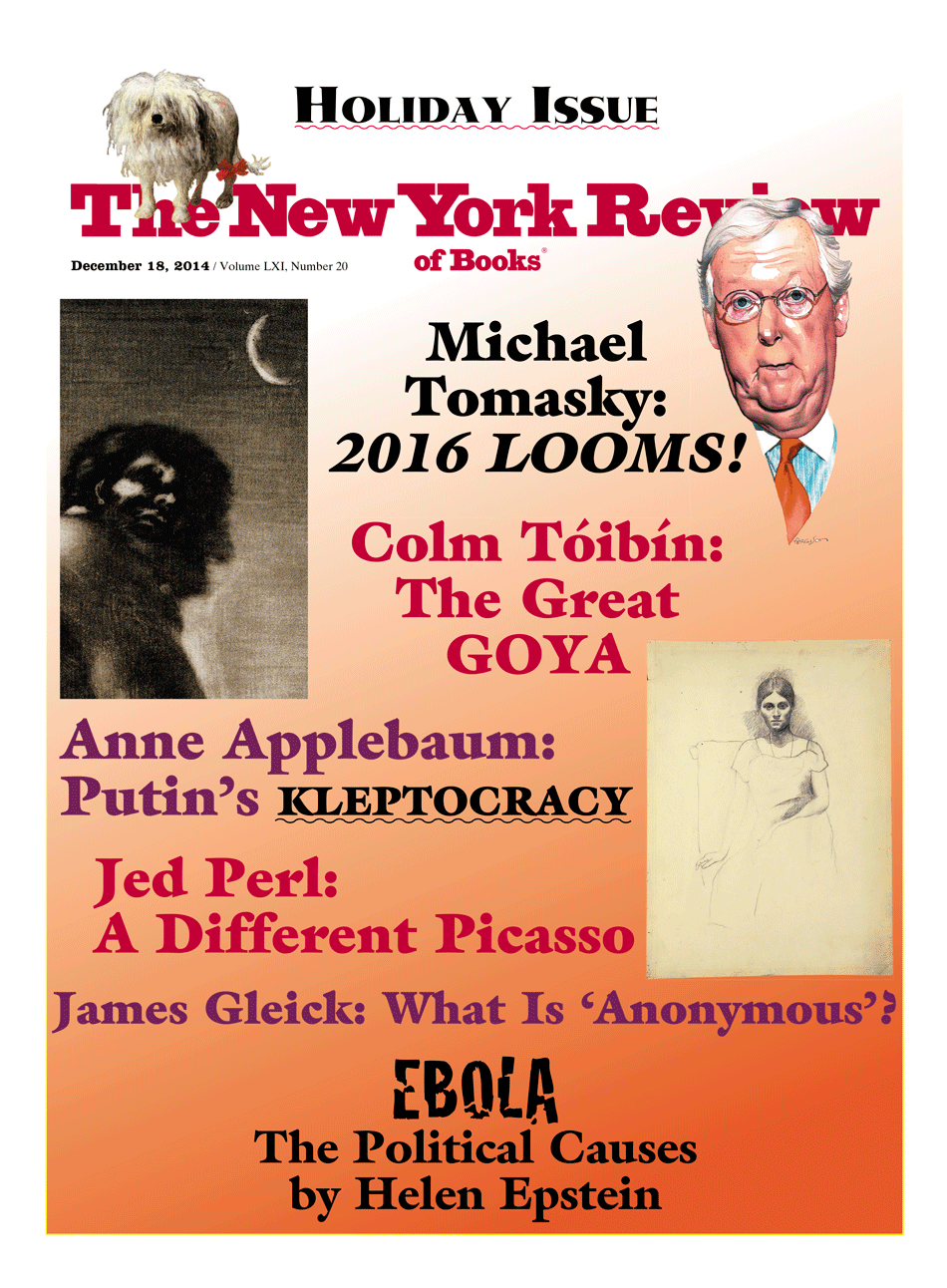

Karen Dawisha’s Putin’s Kleptocracy is not the first book to ask this question. Indeed, she makes extensive use of the work of others, both fellow political scientists as well as journalists working across the US and Europe. Some have found fault with this method, but the resulting work has a certain admirable relentlessness. For by tying all of these disparate investigations together so thoroughly, so pedantically, and with so many extended footnotes—and by tracking down Western copies of documents that vanished from Russia long ago—the extent of what has always been a murky story suddenly becomes more clear. In her introduction, Dawisha, a professor of political science at Miami University in Ohio, explains:

Instead of seeing Russian politics as an inchoate democratic system being pulled down by history, accidental autocrats, popular inertia, bureaucratic incompetence, or poor Western advice, I conclude that from the beginning Putin and his circle sought to create an authoritarian regime ruled by a close-knit cabal…who used democracy for decoration rather than direction.

In other words, the most important story of the past twenty years might not, in fact, have been the failure of democracy, but the rise of a new form of Russian authoritarianism. Instead of attempting to explain the failures of the reformers and intellectuals who tried to carry out radical change, we ought instead to focus on the remarkable story of one group of unrepentant, single-minded, revanchist KGB officers who were horrified by the collapse of the Soviet Union and the prospect of their own loss of influence. In league with Russian organized crime, starting at the end of the 1980s, they successfully plotted a return to power. Assisted by the unscrupulous international offshore banking industry, they stole money that belonged to the Russian state, took it abroad for safety, reinvested it in Russia, and then, piece by piece, took over the state themselves. Once in charge, they brought back Soviet methods of political control—the only ones they knew—updated for the modern era.

That corruption was part of the Russian system from the beginning is something we’ve long known for a long time, of course. In her book Sale of the Century (2000), Chrystia Freeland memorably describes the moment when she realized that the confusing regulations and contradictory laws that hog-tied Russian business in the 1990s were not a temporary problem that would soon be cleaned up by some competent administrator. On the contrary, they existed for a purpose: the Russian elite wanted everybody to operate in violation of one law or another, because that meant that everybody was liable at any time to arrest. The contradictory regulations were not a mistake, they were a form of control.

Dawisha takes Freeland’s realization one step further. She is arguing, in effect, that even before those nefarious rules were written, the system had already been rigged to favor particular people and interest groups. No “even playing field” was ever created in Russia, and the power of competitive markets was never unleashed. Nobody became rich by building a better mousetrap or by pulling himself up by his bootstraps. Instead, those who succeeded did so thanks to favors granted by—or stolen from—the state. And when the dust settled, Vladimir Putin emerged as king of the thieves.

Advertisement

To tell this story, Dawisha uses many sources, including the evidence presented in several major court cases, a number of which fizzled out for political reasons; material collected by Russian and European investigative reporters, some of which has now vanished from the Web; and Russian legal journals, many of which are now out of print. She has also conducted dozens of interviews with businessmen and bankers all over the world. As noted, some of what she digs up has been described elsewhere, not only in Masha Gessen’s emotive account of Putin’s rise to power, The Man Without a Face (2012), but also in Clifford Gaddy and Fiona Hill’s Mr. Putin: Operative in the Kremlin (2013) and Peter Baker and Susan Glasser’s Kremlin Rising (2005).1

Dawisha doesn’t, like Gessen, seek to convey the emotions of Russian politics, and she is less interested than Hill and Gaddy were in Putin’s personal biography. Instead, she turns a relentless focus on the financial story of Putin’s rise to power: page after page contains the gritty details of criminal operation after criminal operation, including names, dates, and figures. Many of these details had never been put together before—and for good reason. Cambridge University Press declined to publish this book after initially agreeing to do so for fear of violating UK libel laws. Although she soon found a US publisher—US libel laws are less constricting—Dawisha’s troubles give some hint of the difficulties faced by many who try to write about Russia, and particularly those who try to describe the corrupt practices of men with very deep pockets and very expensive lawyers on their payroll.

Using this mass of evidence, Dawisha nevertheless argues that the KGB’s return to power begins not in 2000, when Putin became president, but in the late 1980s. At that time, the then leaders of the KGB, who distrusted Gorbachev, began transferring money that belonged to the Soviet Communist Party out of the Soviet Union and into offshore accounts tended by Swiss or British bankers. At least initially, these transfers took place with the Party’s knowledge. In August 1990, the Central Committee called for measures to protect the Party’s “economic interests,” including the construction of an “invisible” structure, accessible only to “a very narrow circle of people.” KGB operatives who already had experience with managing foreign bank accounts—they’d been funding foreign Communist parties for decades—were put in charge.

By the autumn of 1991—after the KGB-led coup in August to overthrow Gorbachev had failed—almost $4 billion belonging to the Party’s “property management department” had already been distributed to hundreds of Party-, Komsomol-, and KGB-managed banks and companies that were swiftly establishing themselves in Russia and abroad. This was an enormous amount of capital in a country that had, at the time, a scarcely functioning economy and hardly any foreign currency reserves at all. In due course, these funds, and the people who managed them, were to become the real foundation for the economy of post-Soviet Russia. Again, this was not robber baron capitalism, or indeed capitalism at all: instead, a small group was enriched by the state and thereby given the means of acquiring its property.

From the very beginning, Russia’s current president had a part in this process. In the late 1980s, Putin was a KGB officer in Dresden, East Germany. There are conflicting accounts of what he was doing there. In his official and unofficial biographies, Dawisha writes, quoting Putin’s German biographerAlexander Rahr, this period is covered in a “thick fog of silence.” But there is some evidence that he may have been helping the KGB prepare for what it feared could be the imminent demise of the Soviet empire. Indeed, when he became president in 2000, German counterintelligence launched an investigation into whether or not Putin had been recruiting agents who would remain loyal to the KGB even after the collapse of communism. As Dawisha explains, “the Germans were concerned that Putin had recruited a network that lived on in united Germany.”

The scale of this effort is not known, but certainly a few of his Dresden contacts have become startlingly successful in the decades since 1989. Matthias Warnig, a Stasi colleague of Putin’s, opened Dresdner Bank’s first branch in St. Petersburg in 1991, by which time Putin was living there. By 2000 he headed all of the bank’s operations in Russia. In 2003, the bank participated in the dismemberment of Yukos, the oil company owed by the jailed magnate Mikhail Khodorkovsky. Since 2006, Warnig has been managing director of the Russian–German Nord Stream pipeline project, a company that won permission to operate during the term of German Chancellor Gerhard Schröder, and that later hired ex-Chancellor Schröder to serve on its board. In 2012, among other high posts, Warnig became a member of the board of directors of Bank Rossiya, one of the Russian banks now under US sanctions.

Advertisement

After leaving Germany, Putin returned to St. Petersburg, eventually making his way, with KGB patronage, into the St. Petersburg city government, where he was responsible for “foreign liaisons”—and where he could put some of his foreign contacts to immediate use. In 1991, Marina Salye, a member of the St. Petersburg city council, accused Putin of having knowingly entered into dozens of legally flawed contracts on behalf of the city, exporting hundreds of millions of dollars’ worth of commodities—timber, coal, steel—in exchange for food that never arrived. Her attempts to censure him came to nothing: the council called for his resignation but nothing happened. At a higher level, Putin had protectors. Salye, spooked by threats, went into hiding and disappeared from Russian politics.

Not that it mattered much, since Putin and his friends had other irons in the fire. Back in this very early post-Soviet moment—when Western advisers were still streaming into the country to give lectures on the rule of law and judicial reform—Putin personally organized, or helped organize, several institutions that exist to this day. One of the best known is Bank Rossiya, which was founded in St. Petersburg in 1990, using money from the Communist Party’s Central Committee. From the beginning, according to Spanish police investigators, Bank Rossiya facilitated cooperation between Putin, other city officials, and Russian organized crime, allowing the two groups to invest together.

Dawisha also describes the origins of the Ozero Dacha Consumer Cooperative, a small group, again including Putin, that conducted property investments but soon branched into other businesses, making use of mysterious sources of cash. At a time when others had no access to capital, they were flush. Most of the members of the cooperative are now millionaires and several are billionaires.

The St. Petersburg Real Estate Holding Company (SPAG) was a third institution linked to Putin. In 1999, the German Federal Intelligence Agency (BND) completed an investigation into SPAG, and published a report that accused the organization of laundering money for Russian and Colombian criminals. Among other things, the BND said that SPAG took money that had been sent out of Russia and was parked “offshore,” and helped its owners—among them the leaders of the Tambov gang, a part of the St. Petersburg mafia—repatriate it back into the country through the purchase of property and other legitimate assets. Notably, when Schröder became chancellor of Germany, this investigation was slowed down; Putin’s name had, in any case, been kept out of it. Several other company founders were indicted by courts in Liechtenstein. Vladimir Kumarin, the former Tambov gang leader, has been in prison since 2012.

Dawisha also describes the origins of the Twentieth Trust, a “construction company” also linked to Putin. According to Russia’s own Ministry of Internal Affairs, the Twentieth Trust received money from the budget of the city of St. Petersburg and subsequently transferred that money abroad. Novaya Gazeta, a Russian newspaper, discovered that the company had purchased property in Spain where it constructed villas using Russian army labor. These kinds of reports led Spanish police to become suspicious of Russian activity in Spain, and in the 1990s they began monitoring the Russian oligarch Boris Berezovsky, as well as several well-known leaders of Russian organized crime, all of whom had houses on the southern coast of Spain. In 1999, to their immense surprise, their recorders picked up an unexpected visitor: Putin. He had arrived in Spain illegally, by boat from Gibraltar, having eluded Spanish passport control.

By the time he made this secret visit to Spain—apparently one of many—Putin had already graduated to the next phase of his career: until August 1999, he was the boss of the FSB, the KGB’s successor organization. He had moved from St. Petersburg to Moscow, taking many of his cronies and all of his criminal connections with him. At that time, they were not the only such group to have parlayed state and KGB money into wealth. President Yeltsin had also in effect given his blessing to the creation of several large fortunes, including that of Boris Berezovksy. But as Yeltsin became increasingly ill and unavailable, Putin persuaded Berezovsky and others in the Yeltsin inner circle that he and his FSB colleagues would be the guarantors of their wealth in the event of Yeltsin’s demise.

They duly anointed Putin prime minister and then president—the wishes of voters and democratic process had little to do with it. But having obtained high office, he turned the tables on them. Soon after taking over, he made it clear that he intended to remove the Yeltsin-era elite and to put a new elite in its place—mostly from St. Petersburg, equally corrupt, but loyal exclusively to him. Among others, he removed the CEO and chairman of Gazprom—the old Soviet gas ministry, now a private company—and replaced them with Dmitry Medvedev, a St. Petersburg lawyer and Putin’s colleague since his days in the St. Petersburg mayor’s office, and Aleksei Miller, his former deputy at the St. Petersburg Committee for Foreign Liaison. Very quickly, Gazprom became a source of personal funds for Putin’s projects, useful, for example, when he needed a large chunk of money to bribe the president of Ukraine. Gazprom’s new leadership grew in wealth and power, and they knew exactly who they had to thank for it. This was not the first time this kind of policy had been deployed in Russia: “Change the elite” is an old Stalinist tactic too.

But having changed the elite, having taken hold of the most important Russian companies, and having established himself as godfather to all of the other oligarchs, Putin did not change his ways. After he became president in 2000, it is true that Putin did preserve some of the language of “reform” in his public statements. He appointed “reformers” to top jobs. He kept open lines of communication with the West, particularly after September 11, 2001, when he saw the possibility of a tactical alliance with the West against Muslim radicalism in Central Asia. He remained open to relationships with NATO and with American and European leaders. In 2004, he even declared that “if Ukraine wants to join the EU and if the EU accepts Ukraine as a member, Russia, I think, would welcome this because we have a special relationship with Ukraine.” He regularly attended meetings of the G8, an organization—including the US, Canada, France, Germany, Japan, Italy, the UK, and Russia—whose rules and raison d’etre had been altered specifically in order to allow Russia to join.

He also carried off an extraordinary public relations coup, and one with far-reaching significance: for four years, between 2008 and 2012, Putin put a seemingly pro-Western, apparently business-friendly, decoy president in charge of the Kremlin. The reassuring presence of Dmitry Medvedev not only inspired Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton’s “reset” in American foreign policy, but lulled almost everyone in Europe into accepting a gangster state as a difficult but legitimate partner. During the four years of the Medvedev presidency NATO’s military readiness declined further, Western financial institutions became more dependent on Russian money, and Western politicians turned their attention to other matters.

Yet during this same period, as during his own presidency, Putin never abandoned the mafia methods Dawisha has so painstakingly described. Instead, he reshaped Russia’s political system in order to ensure that they could continue. Though Dawisha argues that Putin always intended to recreate an authoritarian, expansionist Russia, one could also argue that an authoritarian, expansionist Russia was the inevitable result of Putin’s need to protect himself, his cronies, and their money.

Either way, no one now doubts that, despite the talk of “reform,” he made no attempt to encourage truly entrepreneurial capitalism inside Russia or to create a legal system that would allow small businesses to grow. Courts became increasingly politicized and markets ever more distorted. Oligarchs and businessmen at all levels who did not play by his rules were destroyed. The most famous victim of Russia’s arbitrary justice was Mikhail Khodorkovsky, who was arrested in 2003, after which his oil company, Yukos, was liquidated. Yukos’s assets were then transferred to another company, Rosneft, which happened to be owned by another one of Putin’s friends. Khodorkovsky’s arrest was intended as a lesson to others: here is what will happen, even to the richest men, if they step out of line.

During what seemed at the time to be a golden era of Russian–Western political relations, the economic picture for foreign investors was also mixed. Some Western businesses flourished in Russia, but only so far as it suited Putin and his cronies. Westerners who annoyed the regime—or Westerners whose businesses were coveted by powerful Russians—could be destroyed with tax demands, lawsuits, and worse.

This was the fate of Bill Browder—grandson of Earl Browder, leader of the American Communist Party—who set up a Russian investment fund that invested heavily in Gazprom. After he turned out to be an annoyingly activist shareholder—he kept asking why the company’s accounts were so untransparent—Browder was barred from the country in 2005. His companies in Russia were subsequently destroyed by a particularly Putinist form of corporate raiding: tax officials and police attacked their offices, reregistered them, declared them bankrupt, stole their money, and arrested and harassed their employees. Browder’s lawyer, Sergey Magnitsky, was eventually beaten to death by guards in a Russian prison.

At the same time—while constantly speaking of “reform” in Western capitals—Putin was systematically destroying the nascent institutions of liberal democratic society. Whatever embryonic political movements had come to life in the 1990s were crushed in the 2000s. Refusing to tolerate any real political opposition, Putin instead sponsored phony political parties whose leaders were ultimately loyal to himself. He eviscerated independent media, especially television, which he considered to be an essential tool of social manipulation. Although he left a few very small “dissident” newspapers open, presumably in order to placate the tiny middle class, he pushed back hard when they went too far. Anna Politkovskaya, an extraordinarily brave reporter who wrote about Putin’s war in Chechnya, was one of several Russian journalists to be brutally killed in gangland-style murders.

With the media out of the way, Putin also took on “civil society,” meaning any charitable, educational, or advocacy organizations over which he did not exert direct control. This included the slow suffocation of apolitical groups such as Memorial, the historic human rights organization that has produced internationally admired accounts of the crimes of Stalin, the history of the Gulag, and more generally the history of repression in Russia. Because Memorial had received foreign funding—from organizations such as the Ford Foundation—it was told that it had to be registered as a “foreign agent,” a phrase that heavily implies foreign espionage. More recently, the Russian Justice Ministry has filed a lawsuit that seeks to shut down Memorial altogether, on spurious administrative grounds.2

In place of a genuine media and a real civil society, Putin and his inner circle slowly put into place a system for manufacturing disinformation and mobilizing support on a new and spectacular scale. Once the KGB had retaken the country, in other words, it began once again to act like the KGB—only now it was better funded and more sophisticated. Today’s Russian “political technologists” make use of their state-owned media, including English-language outlets such as the TV news channel Russia Today; armies of paid social media “trolls” who post on newspaper comment pages, as well as on Twitter, Facebook, and other sites; fake “experts” whose quotes can be presented with fake authority; and real experts to whom Putin’s officials have granted special access, or have simply paid. Former Western ambassadors to Moscow, businessmen who have been recruited to Russian company boards, European politicians as high-ranking as Schröder and Silvio Berlusconi—all have been well compensated, directly or indirectly, for offering their support.

Using these different sources, the Kremlin began putting out messages designed not necessarily to make Russia look good, but rather to undermine the Western establishment and Western institutions, including the European Union and NATO. Using both money and information, they seek to empower the Western far right, the anti-establishment left, and the international business community all at the same time. Thus Russia Today supports Occupy Wall Street. A Russian oligarch organizes a meeting in Vienna attended by the French National Front, Hungary’s nationalist political party Jobbik, and Austria’s Freedom Party.3 Whispering campaigns, conducted in the world’s financial capitals—especially Frankfurt and the City of London—hint at the dire things that will happen if sanctions against Russia are not lifted. In an article recently published by The Interpreter, an online publication dedicated to exposing Kremlin disinformation, the journalists Peter Pomerantsev and Michael Weiss argue that

since at least 2008 Kremlin military and intelligence thinkers have been talking about information not in the familiar terms of “persuasion,” “public diplomacy” or even “propaganda,” but in weaponized terms, as a tool to confuse, blackmail, demoralize, subvert and paralyze.4

This is not a system, in other words, that has come about spontaneously, in reaction to events on Kiev’s Maidan, although to those who haven’t followed the evolution of Russian politics over the past twenty years—or to those who have followed only the narrative of “failed reforms”—it might perhaps appear that way. Indeed, in the months since Putin’s invasion of Crimea, it has become fashionable to suggest that the harder-line face that Putin has more recently shown to the world is somehow, once again, the West’s “fault,” that we have provoked Russia into autocratic behavior through our talk of democracy in Ukraine or that—once again—the “reform process” was somehow brought to a halt because the Russians felt threatened by the expansion of NATO or by Western policy in the Balkans.

But after reading Dawisha’s book, and after absorbing the implications of the stories she has so carefully pulled together from so many sources, it is simply not possible to take this argument seriously. Since 2000, Russia has been ruled by a revanchist, revisionist elite with origins in the old KGB. This elite had been working its way back to power since the late 1980s, using theft on a grand scale, taking advantage of the secrecy provided by Western offshore havens, and cooperating with organized crime.

Once in power, the new elite sought to maintain control using the same methods that the KGB always used to maintain control: through the manipulation of public emotion, and by undermining the institutions of the West, and the ideals of the West, in any way that it can. Based on its record so far, it has every reason to expect continued success.

This Issue

December 18, 2014

The Dark & Light of Francisco Goya

You Can’t Catch Picasso

-

1

See also my review of Gessen’s book, The New York Review, April 26, 2012. ↩

-

2

See Gabrielle Tétrault-Farber, “Justice Ministry Moves to Liquidate Renowned Human Rights Group Memorial,” The Moscow Times, October 12, 2014. ↩

-

3

See Jutta Sommerbauer, “Rechte Allianz: Geheimes großrussisches Treffen in Wien,” Die Presse, June 3, 2014. ↩

-

4

Peter Pomerantsev and Michael Weiss, “The Menace of Unreality: How the Kremlin Weaponizes Information, Culture and Money,” 2014, published by The Interpreter and the Institute of Modern Russia. ↩