“Survivors pay with their conscience,” Sybille Bedford observed in her memoir, Quicksands, written in 2005, toward the end of her very long life. Born in 1911 outside of Berlin in Charlottenburg, Germany, she died in London in 2006, just a month before she would have turned ninety-five. She’d endured two world wars and the heedlessness preceding each of them as well as the Holocaust, though from afar, and the painful, impossible, and sometimes exhilarating reconstruction of several cultures: she understood firsthand the burdens of survival. Perhaps as a result she developed her remarkable talent for making the inchoate circumstances we retrospectively understand as “historical forces” seem real, palpable, human. So too “the small things men do to each other every day if they have the power and the lack of imagination, or if their convictions happen to run that way,” as she once noted. “It goes unrecorded, it is hardly voiced, but it lives in the memories of those concerned.”

A Legacy, her finest novel, and superb by any standard, is partly about memory, both personal and cultural.* “We are said to re-invent our memories; we often re-arrange them,” comments its narrator, a woman born shortly before the advent of World War I (like Bedford) who pieces together her peculiar inheritance from the rumors, innuendoes, and snatches of conversation she heard as a child: the tale of a long-ago family scandal that once almost toppled the German government. “In a sense this is my story,” she reflects. “I do not know a time when I was not imprinted with the experiences of others.” Her peculiar inheritance, then, is also the story of Prussian pride, political scandal, anti-Semitism, and moral negligence, which is the legacy, in a word, of the twentieth century.

Bedford did not publish until the age of forty-two, in 1953, when her first, luminous book, The Sudden View (later renamed A Visit to Don Otavio: A Traveller’s Tale from Mexico), appeared only after, as she said, “many desultory years of false starts and failure, hedonism, sloth and doubt.” Actually, hers had been a nomadic life. Her father, Maximilian von Schoenebeck, was a polite and withdrawn aristocrat from Baden in southern Germany. (“Yes, he did lift his hat to the donkey,” Bedford reminisced, “when they met on a walk in the park.”) He preferred to speak French in family conversation; he considered German vulgar. His second wife, Bedford’s mother, was a great beauty some twenty years his junior; partly Jewish, imperious, and Hamburg-born, she insisted on English. Bedford grew up multilingual and torn.

When her parents divorced shortly after World War I, Bedford spent several years living in semiseclusion and semipoverty with her father in the schloss in the German town of Feldkirch that her mother had bought him. They raised chickens and sheep, traded apples for salt and candles, and her father taught her how to uncork a bottle of wine. At night they amused themselves by playing roulette on a real wheel, though if Bedford lost, her chivalrous father refunded her allowance the next day. Only when forced did he send her to the village school, and he immediately pulled her from it when he learned she’d gotten lice. But soon her mother ordered her to Italy, where she was then living, and Bedford left her elderly father, whom she never saw again; he died suddenly in 1925.

For the next fifteen years or so she shuttled between London, where her mother sent her to be educated, and the small fishing port of Sanary-sur-Mer, on the Côte d’Azur, where her mother and young Italian stepfather had moved. In London her education mainly consisted of the long days she spent listening, enthralled, to the cases argued in the legal courts of the Strand. In Sanary she met the colony of artists and writers, including Aldous Huxley and his wife Maria, who had gone there to be near the dying D.H. Lawrence.

Bedford also met the cluster of German refugees who, after the Reichstag fire in 1933, had fled their native country and settled nearby: Lion and Marta Feuchtwanger, Arnold Zweig, Ernst Toller, Franz and Alma Werfel. As she recalled in her two-volume biography of Huxley, a stiff and formal Thomas Mann would read from his latest book while the art historian Julius Meier-Graefe listened absently, more intent on feeding his young wife the white meat of a chicken from his plate. Bedford’s prose is a marvel of such glancing details.

Those years in Sanary were her apprenticeship. She read Flaubert, Stendhal, Proust, Baudelaire, Colette, and Evelyn Waugh. She read Huxley and The New Statesman. She knew she wanted to be a writer, and she began to write in English, choosing it, she later said, as a “rope to save me from drifting awash in the fluidities of multilingualism that surrounded me.” Maria Huxley typed much of her first manuscript, and Aldous offered advice quite devastating at the time. Devastating too was her mother’s spiraling morphine addiction. Again, the Huxleys openhandedly offered emotional support, money, even a ride to the first clinic that her mother had been forced to enter. The situation worsened. “The last I saw of my mother was at Toulon station being lifted through the window of a wagon-lits carriage on a northbound express,” Bedford wrote. “Aldous and Maria stood with me on the platform.” Her mother died in 1937.

Advertisement

By then Bedford’s status as a German citizen in France had become precarious. She could not transfer the money her father had left her into a French bank, so Maria Huxley smuggled some of Bedford’s cash out of Berlin by stashing it in her shoe. When Bedford published an article critical of the Nazis in Klaus Mann’s magazine, Die Sammlung, her German funds were confiscated. “I did not think of consequences,” she recollected in Quicksands; “if I had, I would have written it all the same.” She earned a small income teaching English to refugees—and wrote three rejected novels—but the expiration date on her German passport was drawing near. She didn’t dare return to Germany to renew it. Again the Huxleys intervened. Learning that W.H. Auden had recently married Thomas Mann’s daughter Erika so she could become a British national, they arranged for Sybille to marry Walter Bedford, another obliging gay Englishman.

Safe harbor was short-lived. “By September 1939,” she said, “all existences snapped in two.” Leaving France, she managed to secure passage from Genoa (again, thanks to the Huxleys, now in California) on the very last ship bound for America and stayed in the United States for the duration of the war. Once more she taught English and once more she tried to write. Afterward, before returning to Europe, she and her friend Esther Murphy Arthur decided to visit Mexico. That was the basis of A Visit to Don Otavio. “I had a great longing to move,” she explains in its opening pages, “to hear another language, to eat new food; to be in a country with a long nasty history in the past and as little present history as possible.”

Part memoir, part invention, part hilarious road trip—and a Sophoclean meditation on time, history, and place—Don Otavio is the story of two women in a splendid, volcanic country. Guided by little more than Madame Calderón de la Barca’s Life in Mexico and a trenchant sense of the absurd, Bedford buys a manual of conversation. Turning to the section called “Useful Words and Phrases,” she reads, “‘Are you interested in death, Count?’ ‘Yes, very much, your Excellency.’” Bruce Chatwin called Don Otavio a book of marvels that never stoops to the travel writer’s “cheap ironic asides.” Her prose is lucid, urbane, tart, and owes something to the arguments she’d heard in the Strand: “the blend of gravity and theatre,” she later reminisced. “Transfusion of astringent reason with righteousness and a sublimated romanticism.”

In 1956, Bedford, then forty-five years old, published A Legacy, her first novel. In Britain Nancy Mitford and Evelyn Waugh immediately hailed it as jarring and subtle, bold in scope and design, and Huxley was right when he called it “an unclassifiable book, at once an historical novel and a study of character, a collection of brilliantly objective portraits.”

Consider the characters that Huxley adored: Baron Julius von Felden, known as “Le Beau Jules,” who travels to Berlin with a half-dozen leather suitcases and his pet chimpanzees, Robert and Tzara and Léon, to marry Melanie Merz, the consumptive daughter of a rich Jewish family residing in a sepulchrally opulent house. It is the 1890s, the age of the Impressionists, the age of decorum, the age of pomposity and “of mahogany and the basement kitchen, the over-stuffed interior and the stucco villa.” It’s an age whose wealth is represented by the insular Merzes:

They never travelled. They never went to the country. They never went anywhere, except to take a cure, and then they went in a private railway carriage, taking their own sheets.

While their contemporaries added Corot landscapes to their Bouchers, the Merzes added bellpulls. At the same time, a recently unified Germany was flexing its muscles, much to the consternation of the eccentric and equally insular von Feldens, landed Catholic aristocrats from Baden who dwell in a world, or fantasy, of their own. To them the French Revolution is still alive; the Industrial Revolution has not yet happened. “They ignored, despised, and later dreaded, Prussia; and they were strangers to the sea.”

These characterizations—a bit of Gibbon, a bit of Austen, even a bit of Virginia Woolf—briskly punctuate the novel’s serpentine plot. Though Melanie dies, the Merzes continue Julius’s allowance (actually, they raise it) even after he is remarried to an English beauty of principle, who understands and renounces the intricate, wayward lies of the status quo. Their daughter is the novel’s narrator, who has learned the story of her uncle Johannes (Julius’s brother), a gentle, animal-loving cadet who sometime after the Franco-Prussian War escaped from a military academy only to be carted back, by then a half-mad embarrassment to the army. Placed in charge of a stud farm and mistakenly promoted to captain, he wore no uniform, spoke no words, ate only oatmeal and carrots and milk, and generally spent his days among the horses—until, that is, a fellow officer, sent to investigate, accidentally shot him. “Thus the memory of the boy who was a man and died before I was as much as born, and of the school I never saw, were part of the secret reality of my own past,” the narrator notes.

Advertisement

Unleashing a torrent of abuse from socialists, liberals, anti-Semites, labor leaders, free traders, antimilitarists, and Catholics, all vying for power, all convinced of the rightness of their position, the shooting became a cause célèbre. But the scandal was no different from any other, as the narrator says:

Motive will be everything, but motive as usual will be scrambled. Some of the accusers will be prompted by faction, and some by principle, others will think of morality or self-advancement or their friends and enemies, and most of them will think a little of these all; and nearly everybody will believe he is thinking of that so complexly constituted entity, a man’s conception of his public duty.

A Legacy is also a tragedy of manners. For even as Bedford observes the human condition with a pensive realism lyrically rendered, the lyricism itself is consolatory. “There is usually a generous element in such upheavals,” the narrator acknowledges. “A murmur of tolerance, some staunchness among friends, desire to obtain better things for others.” A brilliantly descriptive writer preoccupied with moral issues, Bedford is not, however, a finger- wagging moralist. Generously, she allows her characters as well as the worlds that they inhabit a certain independence, as when, without any narrative intervention, they speak in delicious dialogues reminiscent of those by Ivy Compton-Burnett:

“She might at least have paid his card debts. Jolly uncomfortable for a man.”

“Think of a woman being able to do that!”

“Has he still got that girl at the Lessing Theatre?”

“Her or another.”

“Sarah can’t have liked that part much.”

“She can hardly like any of it.”

“Oh it’s a bad business any way you look at it.”

“A very bad business.”

Flashes of dialogue, flashes of insight: A Legacy is composed of flashes. A novelist manqué, the narrator’s mother, Caroline, enters a room, and

she, too, was quite detached; the spring to seize, connect, relate, had become slack, and she received the scene before her, the room, the lives, the people, not shaped in terms of judgement or analysis, Thackeray or Trollope, but as an integral and direct impression of something composed of several levels—smoothness lying over painstaking elaboration, an order covering and engendering chaotic agitation and beyond it nothing.

A scene composed of several levels, with an integral first impression: this almost defines the novelist’s aim. Bedford peers into those painstaking and elusive elaborations we come to know as history with a lucidity and a detachment all the more compassionate for being detached. “I had walked in as into an open garden,” Caroline says; “one does not enter that way twice.”

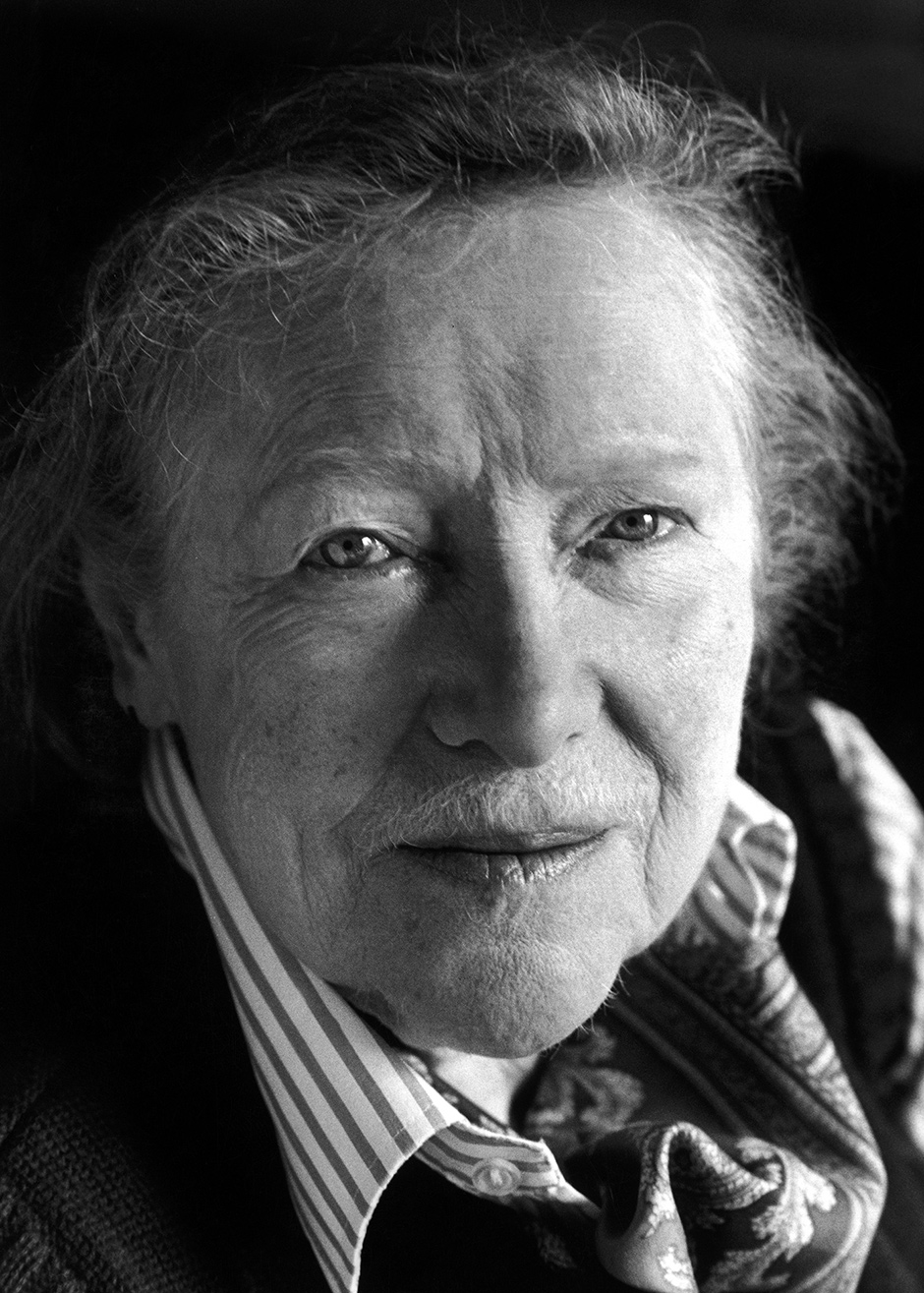

I met Sybille Bedford many years ago, when I went to England to interview her for my biography of Janet Flanner. As I wrote in that book’s introduction, I’d already encountered her while doing research at the Library of Congress, where I’d seen her illegible scrawl on the thin green paper she used to spare her eyes the glare of paper-white. And I still remember my shock when she answered my first query about Janet Flanner on those same green sheets. It made her feel a bit posthumous, she said.

To this day, I also remember her bright blue eyes, her mumbly voice, the bottles of dark wine lined up on the small wooden table in her very small but amply book-lined apartment. I remember that our first talk lasted far into the night. I remember that she was then and continued to be forthright, funny, and scrupulously frank. I remember thinking and then later writing, and considering even now, how remarkable it was that one of the finest stylists of the twentieth century, bar none, with a prose of incomparable precision and grace, would candidly acknowledge her daily battle against discouragement, distraction, and doubt. But that was typical.

I also remember that on September 11, 2001, she was the only friend from afar who telephoned to check on my husband and me. Then again, her life and her work were all about accountability. “Our capacities for suffering are not usually so extensible as are the means of inflicting it,” she once observed.

We bear, and may derive strength from having borne, comfort from being still there, comfort from any mercy: the faith of friends, the match struck by a stranger, discovery of reserves.

That is survival.

Survival takes myriad forms, as she well knew. After the war, working as a journalist, she covered for Esquire and others some of the most sensational cases of the twentieth century: the murder trial of John Bodkin Adams, a physician who was acquitted of killing an octogenarian female patient and was rearrested for a similar crime before he left the courtroom (The Best We Can Do); the prosecution of twenty-two former staff members at Auschwitz (“The Worst That Ever Happened”); the case against Lady Chatterley’s Lover. She was dispatched by Life to cover the Dallas trial of Jack Ruby, and her book The Faces of Justice: A Traveller’s Report is a wry, wise comparative study of the court systems of England, Germany, Switzerland, France, and Austria.

“If a lawyer’s mind means an ability to grasp facts and their implications, a gift of exposition and a willingness to see the other side, then a lawyer’s mind is an asset indeed for any writer,” Bedford wrote. Clarity and the ability to see both sides of a fact shape all of her work, whether her biography of Huxley (a labor of love) or the novels that appeared after A Legacy. A Favourite of the Gods (1963) is about an American woman abroad who believes in pacifism and Lloyd George but dismisses literature and passion in one blow, declaring Proust affected and Madame Bovary unnecessary, and whose granddaughter, Flavia, the callow heroine of A Compass Error (1968), falls recklessly for a sophisticated older woman. Baffled by the consequences, Flavia asks her mother, “How is one to live—if every step leads to another?” Her mother replies, “Like that.”

Mothers and daughters haunt her novels as much as the relation between truth and lies and the courage it takes to soldier on. Bedford consistently asks how, or if, we can get back to those people and places we love, what we owe them, what they still say to us—if, that is, we remember correctly or at all—and how they could rob us even as they gave us everything. She described her fourth novel, Jigsaw, as “a biographical novel” (it was short-listed for Britain’s Booker Prize in 1989), and here again told a family story, this time Sanary and the illusions of freedom—and of the ruination of her beloved, arduous mother. It’s no one’s fault; it’s everyone’s fault.

In A Legacy, Bedford remarks: “Life is never as bad nor as good as one thinks.” Perhaps, and surely novels provide us with at least that consoling perception. That’s just what A Legacy does. Its beautifully wrought depiction of human life as humorous and harrowing, interconnected and splintering, confused, unjust, and sometimes quite kind extends the legacy of the novel. And it makes some sense of our survival.

This Issue

March 5, 2015

Vaccinate or Not?

Our Date with Miranda

France on Fire