Standing in front of Egon Schiele’s full-length portrait of Edith—one of the most striking pictures at the Neue Galerie’s exhibition of Schiele portraits—I thought what a peculiar tribute this was to the young woman he had just married (see illustration below). He had begun a courtship of Edith (as well as her sister Adele) in the spring of 1914, and she became Schiele’s wife, much against the wishes of her family, in 1915. The painting was done the same year. (Another fine portrait in sombre autumn colors, displayed in the same show, of Edith’s father, Johann Harms, a retired railway man, slumped in his chair, asleep perhaps, suggests that just one year later Schiele may have been forgiven for taking Edith away from her family.)

There she is, a gawky red-haired figure squeezed into a milky background, her slim hands clutching a multicolored striped dress, made by herself out of curtain material, her white shoes turned slightly inward, her wide blue eyes peering with childlike innocence from a pale-skinned face. The impression is of a doll-like creature, stiff, timid, not entirely in control of her own limbs. The inexperienced, ultra-respectable Edith Harms, from a Protestant family, would seem to have been an odd companion to a nominally Catholic artist famous (indeed notorious) for his scandalously erotic pictures, many of them of his mistress and model, the free-spirited Wally Neuzil.

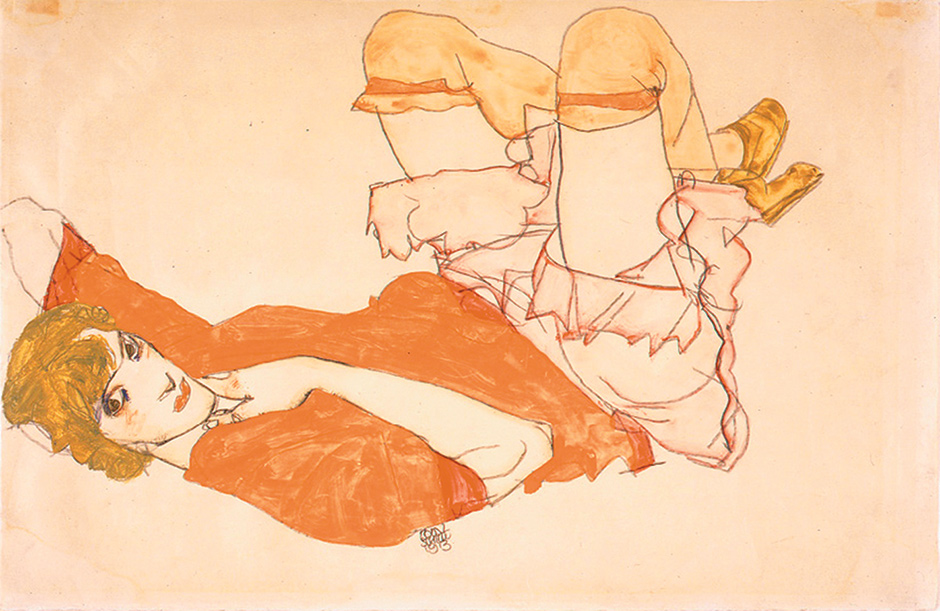

In the Neue Galerie show, the portrait of Edith hangs in the same room as the erotic works, such as the watercolor and pencil drawing of a young girl opening up her vagina like the petals of a rose (Observed in a Dream, 1911), or Wally looking at the viewer anything but innocently with her legs drawn up, as though waiting to be penetrated (Wally in Red Blouse with Raised Knees, 1913).

Wally had been living with Schiele in Neulengbach, a small town in Lower Austria, in 1912, when he was arrested for kidnapping, rape, and public immorality. The first two charges were dropped for lack of evidence. But Schiele’s erotic drawings of young girls were enough to convict him on the third count and send him to prison for twenty-four days. Wally loyally stuck with him, as his mistress. Despite all his bohemian airs, Schiele did not regard her as a suitable wife. Himself the son of a humble stationmaster (who had been driven mad by syphilis at an early age), Schiele wanted to combine his artistic explorations of dark sexuality with the bourgeois comforts of settled domesticity. For this he needed a bourgeois wife.

Edith and Adele Harms lived opposite Schiele’s studio in Vienna. He attracted their attention by making faces and holding up pictures from his window. And he would take them on walks, reassuring them, and their anxious mother, of his honorable intentions by bringing the ever-trusting Wally along with him. He wasn’t sure, at first, who would make a better wife, Edith or Adele. In the end, he chose Edith. Adele had to settle for taking her clothes off for some of her brother-in-law’s drawings.

Ideally, Schiele would have liked his liaison with Wally to continue after his marriage to Edith, in a kind of ménage à trois (at least during the holidays), but Edith insisted that Wally should disappear from their lives, which she did with surprisingly good grace. How painful this was to both of them is revealed in Schiele’s 1915 oil painting Death and the Maiden: the man, resembling the artist, is holding on to the half-dressed woman, whose hands are clasped behind his back as though for the last time. The sepulchral brownish colors and shroudlike bed sheets set the tone. Both people look absolutely miserable.

The conventional opinion about Schiele’s 1915 portrait of Edith is that it betrays his romantic disappointment. His wife may have represented domestic calm, a point of stability in respectable Viennese society, and so forth, but she wasn’t sexy like Wally. It is true that even in the erotic pictures of Edith, and there are a few, such as one with splayed legs (Seated Semi-Nude, 1916), or one embracing her husband from behind, while he places his hand on his genitals (Embrace 1, 1915), she looks demure, indeed a little embarrassed.

There is none of Wally’s sexual knowingness in the pictures of Edith. Nor, on first sight, are they haunted by intimations of death. There is something deliberately morbid about many of Schiele’s pictures: the almost skeletal nudes, with their blood-red elbows and fingers, prefiguring death, even as they engage in sexual acts. In his famous watercolor Self-Portrait in Black Cloak, Masturbating (1911), the artist looks cadaverous, more dead than alive. Schiele was the master painter of decadence, of the dying process of living individuals, as well as of Viennese culture on the precipice of a catastrophic war and the dissolution of a great empire.

Advertisement

So how does the apparently wholesome innocence of Edith’s portrait fit into Schiele’s oeuvre? Is it just an expression of conjugal assurance and erotic disappointment? Or is there more to it? I think there is. Looked at more closely, the picture still reveals Schiele’s fascination with the very Viennese entanglement of sex and death.

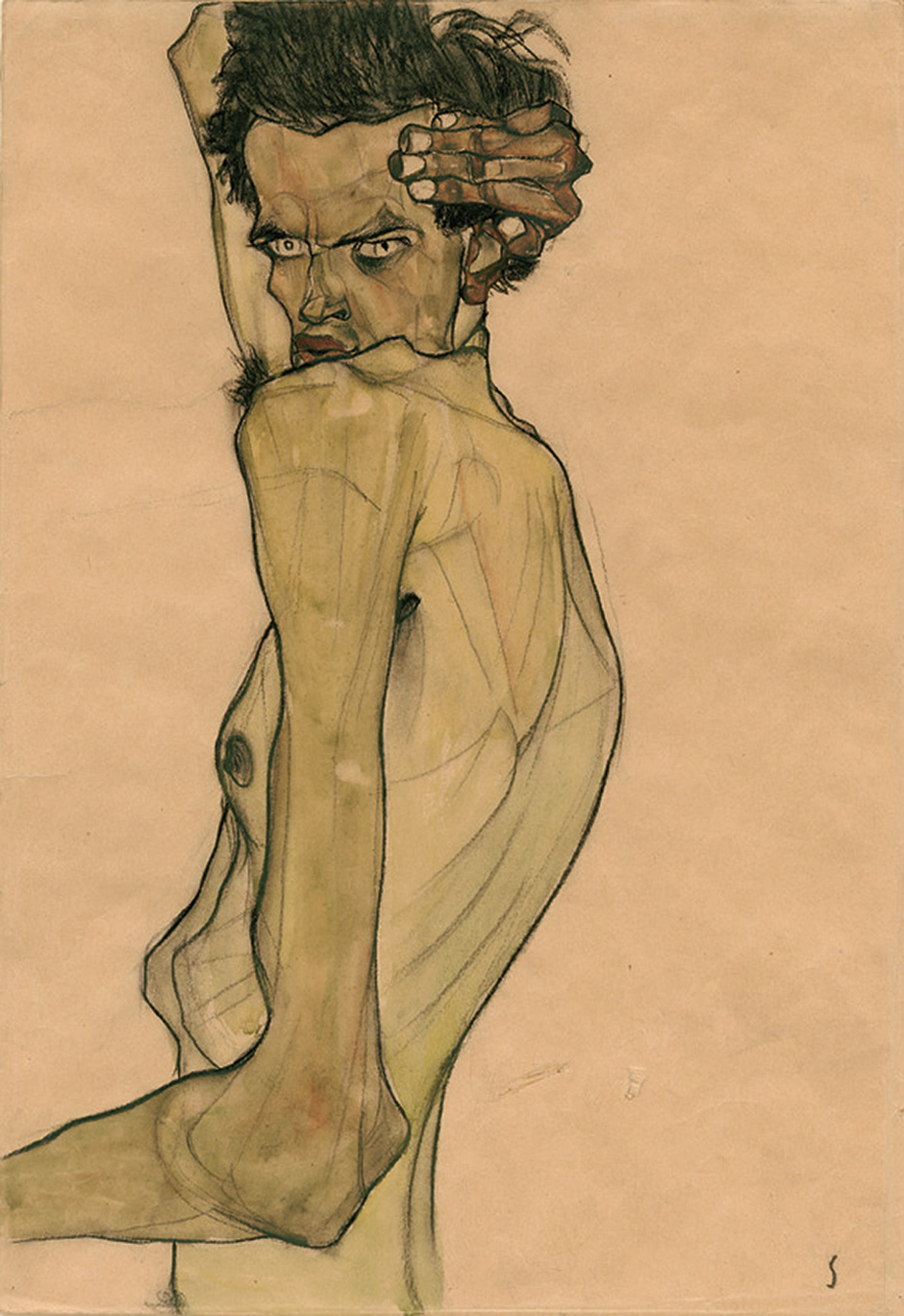

Many of Schiele’s human figures, not just Edith, have a puppetlike quality, including nude drawings of himself. In Self-Portrait with Arm Twisted Above Head (1910), shown at the Neue Galerie, Schiele is contorted like a marionette. In one of his most striking oil paintings, hanging next to the portrait of Edith, we see the artist in a postcoital moment with his mistress. Schiele, looking malevolent, like Nosferatu rising from his coffin, hovers over Wally, who is on hands and knees, drained, spent, like an exhausted dancer.

The puppet can represent many things. One of these is the human body as something to be manipulated at will. Edith’s helplessness, as shown in her portrait, could well have been part of her erotic attraction for Schiele: the shy bourgeoise who could be shaped by the older, more experienced artist. If Schiele was fascinated by decay, he also had an exalted view of artistic power, of the artist as a puppet master, the artist as God.

Schiele made several paintings of a mother carrying a baby in her womb, bursting to come out into the light. One, painted on wood, is entitled Dead Mother (1910). Birth, in this picture, appears to be emerging straight from death. He gave his second Dead Mother painting, done in 1911, the subtitle The Birth of Genius. Schiele had a troubled, and often resentful, relationship with his own mother. Her greatest achievement, he often implied, was to have given birth to a great artist. In a letter to her, he asked: “How great, then, must your joy be—to have given birth to me?”*

He might have shared the deeply Romantic notion of the artist as an almost sacred outsider with his more light-hearted mentor Gustav Klimt. In 1912, Schiele did a large painting called The Hermits of himself and Klimt as martyred saints, Schiele with a crown of thorns wrapped around his tormented face. In their dark robes, they hang together in a kind of danse macabre, still alive but playing with the forces of death.

In many cultures, the sacred outsider is sexually ambiguous, neither man nor woman, like an angel. There are hints of this in Schiele’s pictures too. His Self-Portrait in Black Cloak, Masturbating shows the artist hiding his testicles with both hands held in the shape of a vagina. There are also some fine portraits, in oil and drawings, of Erich Lederer, the adolescent son of one of Schiele’s patrons. They are celebrations of his androgyny, the beauty of a different kind of outsider. The boy is fully alive, yet his face has the pallor of death.

As anyone who has seen good puppet theater—or any child—knows, dolls can look more alive than living beings. One of the most sophisticated forms of puppet theater is the Japanese Bunraku. Even though the puppeteers, dressed in dark kimonos, are on stage, and the words spoken by the dolls come from the storytellers sitting on the side, the puppets seem uncannily alive. So much so that Kabuki theater, which evolved from Bunraku, developed a style in which the living actors mimic the stylized movements of puppets. Since Schiele was a passionate admirer of Japanese prints (and collector; his Japanese erotica were famous in Vienna), there may well be a link between his art and Japanese theatrical conventions.

There are other precedents to Schiele’s sexual puppeteering. Pygmalion was the sculptor in Ovid’s Metamorphoses who fell in love with his own creation of a beautiful woman made out of ivory. After he made an offering to Aphrodite, the sculpture came to life, as Pygmalion had wished. They married and had a son.

Nearer Schiele’s time, we have E.T.A. Hoffmann’s story of the student Nathanael who falls in love with Olimpia, a mechanical wooden doll. (Jacques Offenbach dramatized this story in his opera Tales of Hoffmann.) She is his ideal woman, more devoted to him than any living creature could be. In Nathanael’s words, Olimpia is a “profound spirit, reflecting my whole existence!” In another Hoffmann tale, “Automata,” a man expresses disgust for mechanical creatures, which he calls “those true statues of a living death or a dead life.”

Advertisement

There is no reason to think that Schiele meant his portrait of Edith to be an expression of living death. Nor is she simply depicted as a reflection of his own genius, an updated sculpture of Pygmalion. She is very much a creature of flesh and blood. But then the doll-like quality about figures in Schiele’s paintings does not mean the absence of life.

In 1915, the year he married Edith, Schiele began painting Mother and Two Children III. The mother, as in his earlier treatments of this theme, looks dead or close to death, her eyes hollow and unseeing in a sickly gray face. The two children, both modeled after Schiele’s own nephew, Toni, have the rosy cheeks and healthy tints of rude health. They are dressed, like Edith, in bright multicolored clothes. And yet, again like Edith, they have the stiffness of marionettes, waiting to be animated by a master.

Schiele’s art with its deep sensitivity to death and decay, even in a loving portrait of a newly wed wife, is far more generous than some of his critics allow. What most of his pictures, including the most erotic ones, show is an awareness of human vulnerability. Again, there is a parallel with Japanese aesthetics, not so much in his cherished woodblock prints but in the plays and drawings with their sense of impermanence, the fleetingness of life, the poetry of imminent extinction.

Schiele’s own fate, and that of his models, can be seen as a tragic illustration of his artistic sensibility. In 1917, two years after they broke up, Wally died of scarlet fever, while working as a war nurse in Dalmatia. One year later, Edith, pregnant with Schiele’s child, died of Spanish influenza, the epidemic that killed more people than all the dead in World War I. A few days after Edith’s death, Schiele fell ill and died of the same disease, at the age of twenty-eight.

-

*

Reinhard Steiner, Egon Schiele, 1890–1918: The Midnight Soul of the Artist (Taschen, 1991), p. 65. ↩