Saul Bellow’s Ravelstein—included in the Library of America’s final volume of Saul Bellow’s complete novels—is a eulogy in novel form for his friend Allan Bloom. But it also contains a kind of eulogy for Bellow himself. A shift in emphasis occurs about halfway through when Ravelstein, close to death, predicts that Chick (more or less Bellow’s alter ego) will soon follow him to the grave. Before long Ravelstein is dead and Chick is hospitalized for a potentially fatal case of food poisoning. Chick spends much of the latter part of the novel contemplating death and summing up his life. “I…lived to see the phenomena,” he concludes. Life may pass by in a continuous series of “pictures,” yet “in the surface of things you saw the heart of things.”*

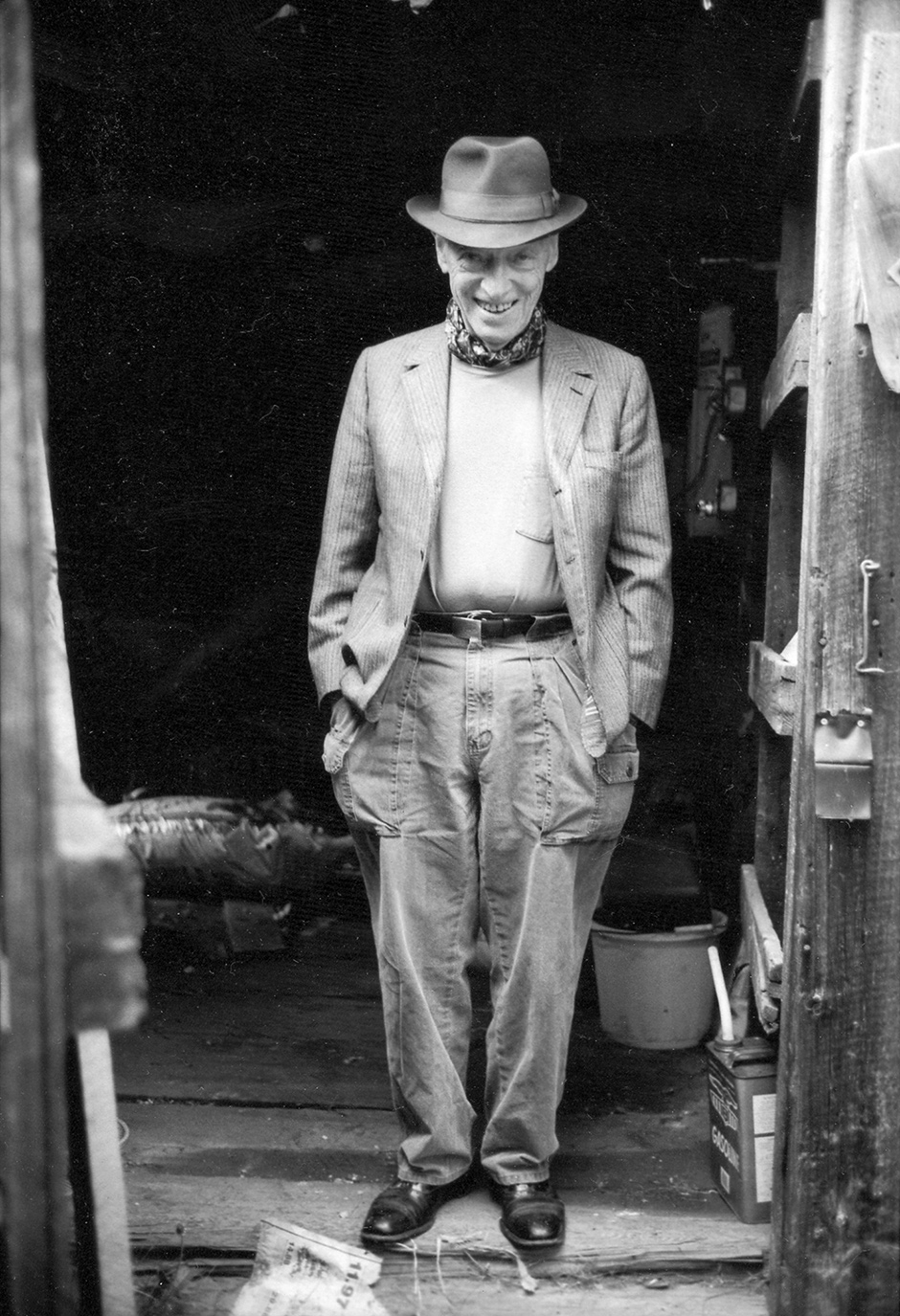

Chick, the author of a biography, has made a career of examining the surface of things to understand the inner lives of his subjects. “Ordinary daily particulars,” he writes, “were my specialty.” The same was true of Bellow in his fiction. He was, in his own term, a world-class noticer. One of the distinctive thrills of reading Bellow is the exuberant richness of his descriptive prose—in the case of Ravelstein, for instance, we glimpse his “honeydew-melon head,” “legs paler than milk” that emerge from an ill-fitting kimono, and a laugh “like Picasso’s wounded horse in Guernica, rearing back.” But Bellow does not summon these details as many novelists do, merely for the sake of clarity or amusement. They are central to his method. They are the way into the hearts of his characters, and also into his own heart.

Zachary Leader, Bellow’s newest biographer, has taken Bellow’s fictional biographer at his word. No detail of Bellow’s life has escaped Leader’s dragnet, no matter how superficial, and all have turned up in the pages of The Life of Saul Bellow: To Fame and Fortune, 1915–1964. Until now, the most authoritative account has been James Atlas’s Bellow: A Biography (2000), a thorough, engaging account that struck many of Bellow’s acolytes, and the man himself, as excessively critical about his personal life and insufficiently admiring of his genius. John Leonard, in his New York Times review, wrote that “a biographer more scrupulous than Atlas is hard to imagine.” But Leader is that biographer. His book is more than eight hundred closely printed pages, at least a third longer than Atlas’s. And it is just the first of two volumes.

Leader is an American who has spent most of his academic career in England, where he is a professor of English literature at the University of Roehampton. Though his previous books, most notably The Life of Kingsley Amis, have focused on British literature, he is not as unlikely a choice as it might initially seem to write an authorized biography of America’s preeminent twentieth-century novelist. Leader is a friend of Martin Amis, Bellow’s most enthusiastic disciple among living novelists, and like Amis and Bellow, is represented by the agent Andrew Wylie, who Leader credits with suggesting the idea of the biography. If Atlas’s biography suffers from the author’s identification with Bellow and later disenchantment with him, Leader’s biography errs on the side of respectfulness, fealty, and fastidiousness. Like Atlas, Leader has spoken to everyone and read all the work (including the abandoned manuscripts), correspondence, and personal papers. He has interviewed nearly everybody alive who knew Bellow, aside from Jack Ludwig, the friend to whom Bellow lost his second wife, Sondra Tschacbasov, an incident that served as the basis for the plot of Herzog. (In his demurral to Leader, Ludwig complained that Atlas had “Swiftboated” him: “I have no ‘side’ to offer…no ‘record’ to ‘set straight.’ Saul was hurt. By his friend. That’s it.”)

Leader has read all the criticism of Bellow’s work and defers to experts whenever possible, citing contemporaneous book reviews, other writers’ criticism, and especially Bellow’s own self-evaluations. He has unearthed an unpublished memoir by Sondra Tschacbasov, written after Atlas’s biography appeared, and Russian ancestry records unknown to Bellow and his family. Leader even spent a semester teaching a course on Bellow at the University of Chicago’s Committee on Social Thought, where Bellow himself taught for more than thirty years. While there he arranged to live in the Cloisters, Bellow’s old apartment building.

Unlike Atlas, Leader has included everything. As a reference work, his book appears unsurpassable. It is a valuable resource, and the prose is clear and poised. The question is, does it pass Bellow’s own test? Does the tremendous accumulation of detail get us any closer to “the heart of things”?

Atlas’s biography begins in 1905, the year that Abraham Belo and Lescha Gordin, Bellow’s parents, married in Saint Petersburg. Leader goes Atlas two generations better, back to Nota Imenitov, Bellow’s patrilineal great-grandfather. (Nota was not a Jew, Leader discovers, a fact that would have come as a surprise to Bellow.) Even as he traces the peregrinations of Bellow’s ancestors around the Pale of Settlement, between shtetls and towns like Dvinsk, Dagda, Druya, Kremenchug, and Lipushki, where Bellow’s grandfather Moses lived beneath a roof of hay, Leader detects a congenital rebelliousness that would reverberate through Bellow’s life and work.

Advertisement

Imenitov, we learn, defied his wealthy landowning father (Bellow’s patrilineal great-great-grandfather) by marrying a Jewish woman, and was promptly disinherited. Moses owned a bakery specializing in Russian bagels and rented a farm with eighty milking cows, but demanded that his children and in-laws handle the businesses, while he devoted his life to study. Bellow’s father, Abraham, forged a license to live and work in St. Petersburg, circumventing Imperial Russia’s anti-Semitic laws; when he was discovered and arrested, he avoided prison by escaping from the police and crossing the Atlantic with his family on a Cunard ship, the Ascania, arriving in Halifax in 1913.

Bellow himself, whose birth in 1915 is not announced until page fifty-six, spent much of his childhood rebelling against oppressive forces. The main one was his domineering father, who struggled to support his family in Lachine and Montreal, and later in Chicago. The fault line appeared where it usually does between an immigrant father and a first-generation American son. “Russian-Jewish fathers were naturally tyrannical,” Bellow wrote in a letter.

Our lives seemed to them a paradise which we had done nothing to deserve…. We were not in awe of their authority. Sensing this, they turned up the heat. But without an authoritarian society to support them, they seemed quite weak, alas, and their storming did not impress us.

As an eight-year-old Bellow underwent an emergency appendectomy, which brought about a series of serious infections and pneumonia. He required four abdominal surgeries, spending nearly five months at Montreal’s Royal Victoria Hospital, where children were allowed only a single weekly visit from a single visitor. In that long period of panicked isolation, during an especially grim Canadian winter, he determined for the first time to become self-reliant. “I had nobody to depend on but myself,” he told Norman Manea in a public conversation seventy-five years later. In the hospital Bellow learned how to keep secrets. He did not tell his parents about the nurses’ anti-Semitism, his own consumption of pork, and his growing fascination with the New Testament, to which the nurses introduced him. It was probably not a coincidence that it was in the Royal Victoria Hospital that Bellow, to occupy the solitary hours and months, became an obsessive reader.

For Bellow the act of writing was itself a form of defiance. When he entered the University of Chicago in the middle of the Great Depression, his father paid “very unwillingly,” before later withdrawing financial support altogether, alarmed that Bellow did not enroll in a vocational track. “To him I am a perverse child growing into manhood with no prospects of bourgeois ambitions, utterly unequipped to meet the world,” Bellow wrote a friend at the time. When, after dropping out of an anthropology graduate program, he devoted himself to writing, he felt isolated, cast out. His father and his two older brothers, who had both become successful businessmen, could not understand what he was doing. Bellow briefly worked at his oldest brother Maurice’s coal yard, but was fired for absenteeism. His first published story, which appeared in Partisan Review in 1941, was titled “9 a.m. without Work.” It was about a young man whose enraged father forces him out of the house each morning to look for a job. “A good boy,” the father gripes, “a smart boy, American, as good as anybody else—but he hasn’t got a job.”

Bellow’s first two novels, Dangling Man and The Victim, were sober, gray in tone, particularly in relation to his subsequent work. Though he later claimed to have adopted a strict “Flaubertian standard,” demanding Continental perfection from his prose, in spirit the novellas were enthralled to Dostoevsky, with their obsessive, impulsive, manic-despairing heroes and existential pathos. The Victim even borrows its central premise from Dostoevsky’s The Eternal Husband: a man is confronted by an angry stranger who holds him responsible for some great misfortune. “Dostoevsky was his idol,” writes Leader, “and ‘American’ reticence his enemy.” But Bellow himself showed reticence in these novels. It was not until a period abroad, in Paris with the support of a Guggenheim fellowship, that he discovered a language all his own.

If his first two austere, high-minded novels represented an effort to break from the immigrant dinginess of his Humboldt Park upbringing, The Adventures of Augie March was a more radical act of rebellion. Its declamatory opening lines—“I am an American, Chicago born…”—are as notable for what they don’t declare: that Augie is a Jew, raised by immigrants, speaking a language unfamiliar to the kind of donnish readers that Bellow courted in his first two novels. Augie March is justly celebrated for its insistence that the experience of a poor Jewish kid from Humboldt Park is no less honorable or worthy of scrutiny than the experiences of, say, The Old Man and the Sea, whose author won the Nobel Prize the year after Augie March’s publication.

Advertisement

Leader quotes Philip Roth’s line that Augie March abolished “anyone’s doubts about the American credentials of an immigrant son like Saul Bellow.” This is the party line on Augie March, but it is not entirely accurate. Others had championed the same themes, and the same subjects; Bellow cited John Dos Passos, Sherwood Anderson, Theodore Dreiser, and James T. Farrell as models. And writers like Henry Roth, Ben Hecht, Daniel Fuchs, and Meyer Levin, to name a few of the more prominent, wrote novels in the 1930s that sought to ennoble the common lives of Jewish immigrants and the language they spoke, often developing new forms and styles in order to do so; Levin’s The Old Bunch (1937) is even set in Augie March’s West Side Chicago neighborhood. As the critic Leslie Fiedler, an old college friend of Bellow’s, observed in the 1950s:

The patterns of Jewish speech, the experience of Jewish childhood and adolescence, the smells and tastes of the Jewish kitchen, the sounds of the Jewish synagogue have become, since 1930, staples of the American novel.

Augie March is the highest example of this form, but its accomplishment far surpasses its value as an expression of ethnic or demotic pride. The novel’s spectacular quality lies in its spirit—exuberant, uninhibited, romantic, easy with absurdity as well as tragedy—and particularly its revelatory prose. Bellow had found in the novel an entirely new and fully realized language, freewheeling and jubilantly profligate, borrowing from both high and low registers: a profoundly American language. Augie March is a prism of self-invention. The novel is about the creation of a human being, Augie, but in its pages we also see Bellow creating himself as a writer. The effect is dizzying. His years of apprenticeship to Flaubert and Dostoevsky had been plowed over by “the discovery of a language that made everything available,” as he told Philip Roth. To Bernard Malamud he wrote:

I took a position in writing this book. I declared against what you call the constructivist approach. A novel, like a letter, should be loose, cover much ground, run swiftly, take risk of mortality and decay. I backed away from Flaubert in the direction of Walter Scott, Balzac, and Dickens.

The novel was greeted with all the acclaim Bellow had coveted and felt that he had been unfairly denied. There were admiring reviews from Lionel Trilling, Robert Penn Warren, and John Berryman, a rave by Delmore Schwartz in Partisan Review (where an excerpt of the novel had earlier appeared), a front-page review in The New York Times Book Review, and a notice in The Saturday Review comparing the novel to Ulysses. Augie March won the National Book Award in 1954 and made the best-seller list. Still Abraham Belo had not softened. In a letter to his son praising him for the success of the novel and sending news of the family, Abraham concludes: “Wright me. A Ledder. Still I am The Head of all of U.”

After Abraham’s death the following year, Bellow devoted himself to Seize the Day, a short novel that has at its center the strained relationship between a son, Tommy Wilhelm, and the disappointed father who loathes him for his dissipation and business ineptitude. Despite the success of Augie March, he returned in Seize the Day to the more restrained tone and narrower ambit of his earlier novels. But the shift, as Leader points out, was not entirely calculated. Seize the Day emerged from “Memoirs of a Bootlegger’s Son,” an autobiographical account of a Russian immigrant in Montreal told from the perspective of his son, which predates Augie March. An early working title was “Jews.”

The abandoned novel is one of Leader’s main sources for his description of Bellow’s youth and his family’s history. Though Leader issues all the proper advisories, the boundary between the life and the fiction in his biography remains gauzy, with Leader alternating between real people and their fictional counterparts whenever he sees an opening. To discuss the strain in Bellow’s first marriage, for instance, he analyzes the relationship between Tommy Wilhelm and his wife Margaret (“Arguments between Bellow and Anita seem to have been no less charged and intractable”), just as he finds clues in the novel for Bellow’s relationships with his father and his mother.

Some of the parallels are more convincing than others, but readers wary of looking too deeply for autographical meaning in fictional characters—readers wary of the biographical fallacy—will find much to cringe at in this strategy, which surfaces on nearly every page of the book. Bellow himself was one of those wary readers. No matter how transparently he exploited those closest to him for his novels, he rejected this type of biographical criticism. This was true even in the case of Abe Ravelstein, who Bellow readily admitted was based on Allan Bloom:

There is a strange literalism that’s become a habit in America. People only want the factual truth…. It’s a curious process. Life is obviously feeding you, yet Ravelstein is a composite, taken from 100 different streams, like all of my characters.

There may be no better exemplar of that strange literalism than Leader’s biography, which continues through two more major novels, both of which in turn thwarted the expectations of Bellow’s editors, readers, and critics. Henderson the Rain King, partially inspired by his reading as an anthropology student at Northwestern and Wisconsin, is the comical-absurdist story of a WASP millionaire who visits African tribes in search of enlightenment and spiritual fulfillment. Bellow struck a truculent tone with a preemptive essay in The New York Times Book Review, published a week before the novel’s release. “Deep Readers of the World, Beware!” warned against looking too closely for symbols and allegory in fiction. Yet readers of Henderson the Rain King, as Leader points out, could see plainly that Henderson “was meant to personify America”; in a critical Partisan Review essay, Elizabeth Hardwick argued that Bellow’s Times essay was “part of the joke.”

Herzog was another reversal, a “novel of the 1960s” that was at odds with the zeitgeist. “Are all the traditions used up?” asks melancholy, erudite, crabby Moses Herzog—a far cry from inarticulate Eugene Henderson’s “I want, I want, I want!” Horrified by the chaos of his disintegrating marriage and the amorality of modern life Herzog turns inward, seeking refuge among the higher planes of intellectual thought. But he finds no peace there, just more confusion. He only feels happiness—“idiot joy”—when he retreats to his home in the Berkshires, where he is comforted by his gentle, patient lover, the intense blue color of the distant hills, and an exhilarating sense of his own mortality. Leader’s book ends with Herzog finding salvation and Bellow catapulted by the novel’s astonishing success to wealth, fame, international acclaim, and a dominant position in American intellectual life. “He had arrived at the pinnacle of American letters,” writes Leader, “and he knew it.”

That may be so, but Bellow never shook the feeling that he was being denied his proper due. “Somehow, under deep layers, the old irremovable feeling lurks that I am a born slightee,” he wrote to a friend in a letter announcing that he had won a Guggenheim fellowship. Even in the afterglow of Herzog he was dissatisfied: “I sometimes think this prosperity may be the world’s way of telling the writer that if his imagination succeeded in one place it failed in another,” he wrote to a different friend. “It did well enough in a book, but now ‘this is how things really are.’”

“How Things Really Are” would be an appropriate title for a magnificent new collection of Bellow’s essays. Edited by Benjamin Taylor, who previously oversaw Bellow’s Letters, There Is Simply Too Much to Think About is a welcome counterweight to Leader’s Life. The collection, organized chronologically, reads like autobiography, only one restricted to Bellow’s inner life, absent the gossip, critical surveys, and trivia that are the grist of any biography. In his nonfiction Bellow tends to sound a lot more like Herzog than Henderson, though he began making broad, bold declarations about modern life and the state of literature long before he became America’s most celebrated writer. Though the volume runs from 1948 to 2000, Taylor inserts as a prologue an essay published in 1975 called “Starting Out in Chicago.” It’s a wise decision and not just because the essay is an account of Bellow’s youth. Its theme prepares the reader for what will follow. “The enemy,” writes Bellow, “is noise.”

By noise I mean not simply the noise of technology, the noise of money or advertising and promotion, the noise of the media, the noise of miseducation, but the terrible excitement and distraction generated by the crises of modern life. Mind, I don’t say that philistinism is gone. It is not. It has found many disguises, some highly artistic and peculiarly insidious. But the noise of life is the great threat…. The sounds of the public sphere, the din of politics, the turbulence and agitation that set in about 1914 and have now reached an intolerable volume.

This divide between “the Great Noise” and “the quiet zone” of contemplation, without which serious, sustained thought is impossible, was more than a motif for Bellow; it was the main artistic crisis of twentieth-century America. His obsession with the subject is the dominant theme of the collection, and reflected in many of the essay titles: “Distractions of a Fiction Writer,” “Machines and Storybooks: Literature in the Age of Technology,” “A World Too Much with Us.” “We all live in the midst of a great deal of public noise and the events of the times have a very strong claim on us,” he said in a 1970 speech delivered in Tel Aviv. “The question is, How do you overcome this noise?”

I don’t really know whether art can exist without a certain degree of tranquillity or spiritual poise; without a certain amount of quiet you can have neither philosophy nor religion nor painting nor poetry. And as one of the specialties of modern life is to abolish this quiet, we are in danger of losing our arts together with the quiet of the soul that art demands.

Readers with any knowledge of Bellow’s personal life may wonder whether the “Great Noise” ringing in his ears might have been the pandemonium of his five marriages, which produced four children, or his fiery relationships with friends, family, editors, and literary rivals. Did Bellow, like Herzog, seek refuge from a turbulent personal life in philosophical ruminations? Perhaps, but so did Socrates. As Bellow’s contemporaries age out, the controversies over the representation of real people in his novels, so central to Leader’s biography and its predecessors, will lose their fascination. (I suspect they already have for most of Bellow’s younger readers.) If Bellow continues to be read, it will be for the exuberant prose, the rigorous wrestling with ideas, and the exquisitely vivid evocation of the eras and places that he occupied. In a noisy world, his fiction creates a refuge—a quiet zone.

Bellow’s anxiety, as he himself points out—citing José Ortega y Gasset, William Wordsworth, Paul Valéry, and Heraclitus—is nothing new. Writers have always struggled to negotiate between life’s daily commotion and the quietude necessary for contemplation. Not all writers have come down on the same side of the matter. Kate Chopin wrote at home surrounded by her seven screaming children; Ernest Hemingway and Aharon Appelfeld wrote in busy cafés. And surely taking monkishness to its extreme can be suffocating—one thinks of J.D. Salinger in Cornish, New Hampshire, ascetic to the point of muteness. Bellow himself understood that there needed to be a balance. For all his renunciation of the Great Noise, he was an avid participator in it. He gave speeches at cultural centers, attended academic symposia, taught university courses nearly until his death, wrote letters to the editor, and joined causes. He led an active social life. In “Reflections on Alexis de Tocqueville” he approvingly quotes Wyndham Lewis: “The writer belongs where the public is.”

The contradiction is never neatly resolved in the essays, just as it is not resolved in his fiction. Bellow’s essays bear the mark of a novelist’s sensibility. He is comfortable with contradiction, hostile to didacticism (though at times he can’t help himself), and he applies the same intense scrutiny to ideas as he does to his characters. The essays gain power from being read in aggregate. What seems at first to be the grumpy bemoaning of a crotchety Herzogian senior (the world is too noisy!) deepens with elaboration. The crank is revealed to be a prophet. For Bellow is right, after all. The world is too noisy. And it is getting noisier every day.

The problem is not really technological or literary. It is moral; it is a human problem. In “A World Too Much with Us,” written forty years ago, Bellow identifies the source:

For a very long time the world found the wonderful in tales and poems, in painting and in musical performances. Now the wonderful is found in miraculous technology, in modern surgery, in jet propulsion, in computers, in television and in lunar expeditions. Literature cannot compete with wonderful technology.

Technology has only become exponentially more wondrous since Bellow wrote those sentences. Still he goes further, arguing that literature, resigned to cede wonder, information, and even imagination to technology, has withdrawn from the world, retreating into pure storytelling. But storytelling without ideas is thin soup. It was one of Bellow’s greatest insights that fiction, more than any other form, could bring us closest to resolving our most complex, abstract questions. “A novel of ideas,” he writes,

becomes art when the views most opposite to the author’s own are allowed to exist in full strength. Without this a novel of ideas is mere self-indulgence and didacticism is simply ax-grinding. The opposites must be free to range themselves against each other and they must be passionately expressed on both sides.

Much of the energy of Bellow’s fiction derives from this tussle between opposites—think of Herzog, stuck between murdering his wife’s new lover and retiring to the Berkshires for a life of solitary reflection, or Charlie Citrine in Humboldt’s Gift, careening between run-ins with Chicago mobsters and extended meditations on the theosophical teachings of Rudolph Steiner. The novels exemplify the highest claims that Bellow makes in his essays about the power of literature. Fiction, which engages not only the reader’s intellect but also his or her imagination and sense of empathy, has a unique capacity to carry us most deeply into “the heart of things.”

But There Is Simply Too Much to Think About is not merely a complement to Bellow’s fiction. It is an intimate portrait of Bellow’s defiant, irascible mind, and a milestone of twentieth-century criticism. Besides the many essays about literature and modern culture there are also revelatory memoirs about his own novels, movie reviews, reporting trips through Spain and Illinois and Israel, ruminations on Jewish identity, critical essays about Hemingway, Ralph Ellison, and Philip Roth, and much else. The collection offers a triumphant overabundance of riches—which is exactly why we read Bellow in the first place.

-

*

Ravelstein, together with What Kind of Day Did You Have?, More Die of Heartbreak, A Theft, The Bellarosa Connection, and The Actual, has been newly published in the Library of America’s final volume of Saul Bellow’s complete novels, Novels: 1984–2000. ↩