In his long, exceptionally prolific career, encompassing over fifty titles in fifty years, Jerome Charyn has attracted the warm respect of critics and fellow writers, if not a mass public following. Walking a tightrope between high literary sophistication and pop culture (his first two loves were comic books and movies), he has managed to elicit comparisons to all the B’s: Bellow, Babel, Borges, and Balzac. His debut novel, Once Upon a Droshky (1964), a comic romp involving Yiddish stage veterans on Second Avenue, was followed by works exhibiting remarkable range in almost every genre: crime novels featuring his memorable police inspector Isaac Sidel, film criticism, memoirs, urban meditations, travel, a lively romance set in Stalinist Russia (The Green Lantern), biographical studies (Joe DiMaggio, Isaac Babel, Marilyn Monroe), graphic novels, and historical fiction (including, most recently, first-person novels in the voices of Abraham Lincoln and Emily Dickinson). For all that restless shape-shifting, there are certain constants in Charyn’s work: an energetic, urbane prose, a playful approach to narrative, a fascination with history, and a downbeat, noirish perspective. This fatalistic outlook coexists comfortably with the ebullient verve and propulsion of his prose.

The Bronx, where the author grew up, has been a recurrent, almost a talismanic object of scrutiny for him. The exodus from the outer boroughs to Manhattan is, as Norman Podhoretz famously put it, “one of the longest journeys in the world.” The story of that transit has been told as well by Alfred Kazin, Norman Mailer, Jay Neugeboren, Vivian Gornick, Kate Simon, and a score of others. In Charyn’s case, the mode of escaping the Bronx was via Manhattan’s High School of Music and Art, followed by Columbia University, and much globetrotting thereafter, spending many years in Paris, and ending up in Manhattan, where he currently resides. His relationship with the Bronx has consequently been largely one of memory.

In an author’s note to his current book, Bitter Bronx: Thirteen Stories, he writes eloquently of that relationship:

For a long time I couldn’t go back to the Bronx. It felt like a shriek inside my skull, or a wound that had been stitched over by some insane surgeon, and I didn’t dare undo any of the stitches. It was the land of deprivation, a world without books or libraries and museums, where fathers trundled home from some cheese counter or shoe factory where they worked, with a monumental sadness sitting on their shoulders, where mothers counted every nickel at the butcher shop, bargaining with such deep scorn on their faces that their mouths were like ribbons of raw blood, while their children, girls and boys, were instruments of disorder, stealing, biting, bullying whoever they could and whimpering when they had the least little scratch.

Eventually, however, it struck him that “I’d been like an amnesiac during my self-banishment from the Bronx, never realizing that each sentence I wrote had come from these Lower Depths.” So he has returned, in a manner of speaking, to that borough, though many stories in this collection take place on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, “amid that solid wall of Art Deco palaces along Central Park West” to which Charyn’s more successful Bronxites have escaped. The Bronx in his stories is the place the big shots came from and want to forget. They drive around in limousines, have dazed wives who shop and dine compulsively at Rumpelmayers, and, when their businesses suffer setbacks, their children take them in, relocating them from thirty-room apartments to their own measly fifteen-room suites in the San Remo.

Meanwhile, the Bronx lurks in memory’s shadows, the place where the financial flimflams that undergirded these fortunes were learned and perfected. It’s the place where the super’s son first sexually fumbled with a teenage girl above his social class, before he was humiliated and driven away. It’s a refuge hidden in plain sight: bandits from elsewhere can hide out in “a particular casbah called the Bronx…a casbah that no one cared about.” Like Chinatown in the movie of that name, the Bronx is where the dirty secrets are kept: where the undesired child has been put away in an institution. Charyn has confessed to his fascination with Raymond Chandler, and one story, “Little Sister,” contains enough echoes of The Big Sleep to work as an homage.

There’s very little to be found about today’s Bronx in these stories. Charyn has no desire to play at sociology or research. He dwells here on a handful of landmarks that affected his childhood—the Loew’s Paradise, William Howard Taft high school, the Lorelei apartments, the classy Grand Concourse of the 1950s, Arthur Avenue’s restaurant row—and he shapes these prelapsarian institutions into a personal mythology. The great event dividing before and after is seen as the construction of the Cross-Bronx Expressway.

Advertisement

“Robert Moses’ highway serves as a not so silent character in these stories, a phantom that crawls between the lines,” he tells us in the author’s note. It helped turn the South Bronx into “the poorest, most crowded barrio east of Mississippi.” Though urbanists today acknowledge that Moses also made substantial contributions to the city’s betterment, Charyn is not having any of it. A dedicated student of crime, he sees Moses’s intervention as the ultimate felony: urbicide. The Bronx “never recovered from the highway Robert Moses had plowed right through it…. Robert Moses’s highway was like the avenue’s own sore rib.”

Whether writing about Yiddish theater or silent film or movie palaces or old Bronx neighborhoods, Charyn is the curator, celebrant, and mourner of lost worlds. “Angela was born a little too late, after the Loew’s Paradise had been chopped into pieces,” he writes in one story, “The Cat Lady’s Kiss.” An Albanian chieftain hankers after an Italian girl, Angela, who works at a market on Arthur Avenue. Finally persuaded to accept the chieftain’s marriage proposal, she discovers that her spouse is a female. Or as Charyn puts it, springing his plot surprise: “The lord of all the Albanians in the Bronx had a clit.” This doesn’t bother Angela, who likes women, but the chieftain’s gang is incensed and they kill their leader when he/she shows up in a dress. Angela then goes back to working on Arthur Avenue as if nothing has happened, “as if she’d dreamt of that warrior king from Little Albania….” Sleep and dream close many of these stories, erasing the complications that preceded.

Now in his late seventies, Charyn retains his youthful enthusiasm for gangsters (Frank Costello, Louis Lepke, and Meyer Lansky all turn up in his fiction), con artists, gamblers, chiselers, and beauties of all types, which he credits in part to his early infatuation with the movies. In his excellent 1989 collection, Movieland: Hollywood and the Great American Dream Culture, he wrote:

I can say without melodrama, or malice, that Hollywood ruined my life. It’s left me in a state of constant adolescence, searching for a kind of love that was invented by Louis B. Mayer and his brother moguls at Paramount and Columbia and Twentieth Century–Fox.

I’ve hungered for dream women, like Rita Hayworth, whose message has always been that love is a deadly thing, a system of divine punishment. Whatever she might say or do, Rita couldn’t care less. She was so powerful she could perform the most erotic dance by simply taking off her gloves (in Gilda).

Charyn’s women characters, from the ones in a pair of memoirs (which read more like fiction) about growing up in the Bronx, The Dark Lady of Belorusse and The Black Swan, to the latest stories in Bitter Bronx, tend to be angelic, hypnotic, or crooked femmes fatales who might have stepped down from the screen.

Not only was his erotic imagination spawned by movies; equally important were the dreaming-while-wide-awake aspect, the flashbacks and jump cuts rearranging time, and the preposterous yet engrossing plots of pictures like Gilda:

Movie time has its own logic and laws, related to little else in our lives…. We dream our way through all these events, involved with the crazy continuum of present, future, and past….

Finally, he took from movies a certain disembodied, spectral quality. While engrossed in a film, “I’m a ghost ‘on the wrong side of the celluloid,’ almost as immaterial as those figures I’m watching, involved in their ghostly dance.”

In Movieland, he quotes approvingly Chandler’s statement that film was

not a transplanted literary or dramatic art…it is much closer to music, in the sense that its finest effects can be independent of precise meaning, that its transitions can be more eloquent than high-lit scenes, and that its dissolves and camera movements, which cannot be censored, are often more emotionally effective than its plots, which can.

It seems to me that Charyn, who’d taught film and written for the director Otto Preminger, has tried to incorporate these cinephile lessons into his latest collection of short stories. There are passages that freeze-frame on an image; past and present are shuffled and reshuffled; and complex plots defer to lyrical cutaways.

The word “shadows” recurs ritually throughout, not just as noir backlighting but as perhaps a crepuscular intimation of mortality on the part of an aging author, or a feared dissolution of identity: “She was searching for shadows and ghosts, and for the shadow of herself.” And of course, “Robert Moses’ ghost had come back again and again to haunt the neighborhoods he had ruined.”

Advertisement

Ghosts pop up everywhere, both figuratively and literally, like in the story “Princess Hannah,” where the protagonist, Harrington,

always existed at the edge of things. He was a packer at the chocolate factory, earned decent money, but he was paid off the books. The factory loved to hire “ghosts” like Harrington.

In a botched robbery, Harrington’s accomplice, Scooter, is shot dead. Later, homeless, Harrington tries to rob a man in the street who turns out to be the ghost of Scooter. He becomes a “highwayman” (note the archaic term) and is eventually shot by a plainclothesman. The story ends with him collapsing into his benefactress’s arms. “Ah, he felt secure against her damaged skin. He wasn’t dreaming now. ‘Darling,’ she said, just before he died.”

Another story, “White Trash,” ends almost identically: “She caught a glimpse of the snub-nosed gun that rose out of a holster she hadn’t seen. She didn’t even hear the shot…. She fell into Omar Kaplan’s arms like a sleepy child.” The prose is part hard-boiled pulp, part Borges, where gaucho knife-fighters cut each other up but the blood stays unreal, oneiric. We don’t feel saddened or affected by the death of these characters, since they were never fully developed in the first place. Their extinction registers as yet another capricious plot twist in a mix-and-match game of reversals, recoveries, and revelations.

Whether such fulsome imagination as Charyn has long demonstrated is a pure gift or has a downside depends on how much original mind one is able to perceive underneath. His fecund fabrications bring us back to picaresque tradition, even as they make us doubt the solidity of the worlds being so cheerfully constructed and taken down before our eyes. We can admire Charyn’s Scheherazade skill at invention, however thinly imagined in places, but ultimately it is not the plots that register deepest in these stories.

What matter most are the aphoristic digressions, the atmospheric descriptions and sheer knowingness of the prose. This, for instance, from the end of the story “Adonis” about a trip through the garment center:

We drove down to Shmatahland in his limousine. The streets were cluttered with men and boys wheeling enormous carts of merchandise—Seventh Avenue had a hum I’ve heard nowhere else, the sound of human traffic spinning off the walls of buildings, bouncing up and down, until the air itself was swollen with a soft, incessant noise that entered showrooms and factories right under the roofs. I wasn’t sentimental about my stay in Shmatahland. I was a high-priced prisoner of war. But there was nothing diabolic about that noise. It was the hubbub of angels, brutal and busy, but angels nonetheless.

In one of the most beautiful (and thickly imagined) stories here, “Dee,” Charyn places himself in the mind of Diane Arbus trying to take her famous picture of the Jewish giant with his diminutive, awe-struck parents. Again, the prose impresses with its accumulation of apt details, fresh diction, and serpentine syntax:

She’d photographed Charles Atlas at his home in Palm Beach, had caught him among his trappings, the mile-long drapes, the chandeliers, the crystalline lamps, and there he was, a seventy-six-year-old muscleman who’d marketed himself and now looked like a tanned monster waiting for his death; she’d unmasked the quiet dignity of dwarfs in rooming houses; she’d photographed mothers with swollen bellies in the backwoods of South Carolina, captured the undaunted look of campers at a posh camp for overweight girls in the heart of Dutchess County; she’d revealed the mad, wrinkled fury of Mae West in her Santa Monica fortress, but she failed year after year with Eddie Carmel.

Sometimes the very speed with which he sets up a story can amuse. Here is the beginning of “White Trash”:

Prudence had escaped from the women’s farm in Milledgeville and gone on a crimefest. She murdered six men and a woman, robbed nine McDonald’s and seven Home Depots in different states.

Are we supposed to believe any of this? Does the author even believe it or is he just having fun with a compressed crime spree montage? Charyn does not seem to be one of those experimental writers who is dead set against naturalistic fiction: rather, he follows its conventions for a while, then mixes in fabulist or fairy-tale elements, referring to La Fontaine and Sir Fox in one story, ending another with “She flew across the street in one spectacular stride—like a witch or a girl who had rediscovered dancing after a lapse of thirty years.”

He keeps nudging these stories toward the angelic, the miraculous, the demonic, though subtly, like in the above sentence, transferring the woman first into a witch and then taking it back by making her merely a dancer. Hints are sprinkled of metamorphoses from human to animal (“she had the feline quality of a silver fox”). The most frequent magical transformation is the erotic obsession: an old man “can’t stop dreaming of Alice’s eyes”; a successful woman lawyer can’t stop thinking about a shady guy she met in the King Cole lounge; a schoolteacher is “addicted to Tanya,” a student he is helping prepare for the SAT test. “He wanted to knead her flesh, kiss her until his mouth was blue with mad desire.”

Like the sudden deaths of other characters, alluded to earlier, these rather Balzacian instances of being smitten with a ruling passion have to be taken on faith. They arise out of nowhere like random strokes of fortune or misfortune. Clearly useful to the storyteller in giving narrative ballast to an otherwise balky story, they also point to what might be called the Rita Hayworth effect: the intrusion of some uncanny, bedazzling presence into mundane, frumpy, everyday reality.

Is Charyn truly a romantic or a trickster? Hard to say, on the basis of these entertaining stories: probably both. They are written with confidence, fluidity, mischievous aplomb, and a lifetime’s worth of acquired literary skill. A light ironic touch peeps through these tales of doomed passion, as though the septuagenarian Charyn were mocking his own former searching for a movie-type love, his previous “constant adolescence” of hungering for dream women. Rather like Luis Buñuel in his last movie, That Obscure Object of Desire, skeptically casting two actresses in the part of the femme fatale, as though finally it doesn’t matter who or what proves to be the precipitating instrument of male folly, we come around to the author’s cheerful pessimism. One way or another, it is not going to work out.

All that infatuation and remorse has pulled Charyn back into the Bronx, the fetal cradle where the trouble started. You can take the boy out of the Bronx, apparently, but you can’t take the Bronx out of the boy. Yet in spite of the book’s title and his initial dread about returning, Charyn is not here expressing bitterness toward the Bronx; if anything, he seems retrospectively fond of the place, overall. What bitter feeling he has is directed toward a world that is increasingly polarized between rich and poor, that does not know how to prize or preserve a grungy, lower-middle-class paradise like the Bronx of his youth.

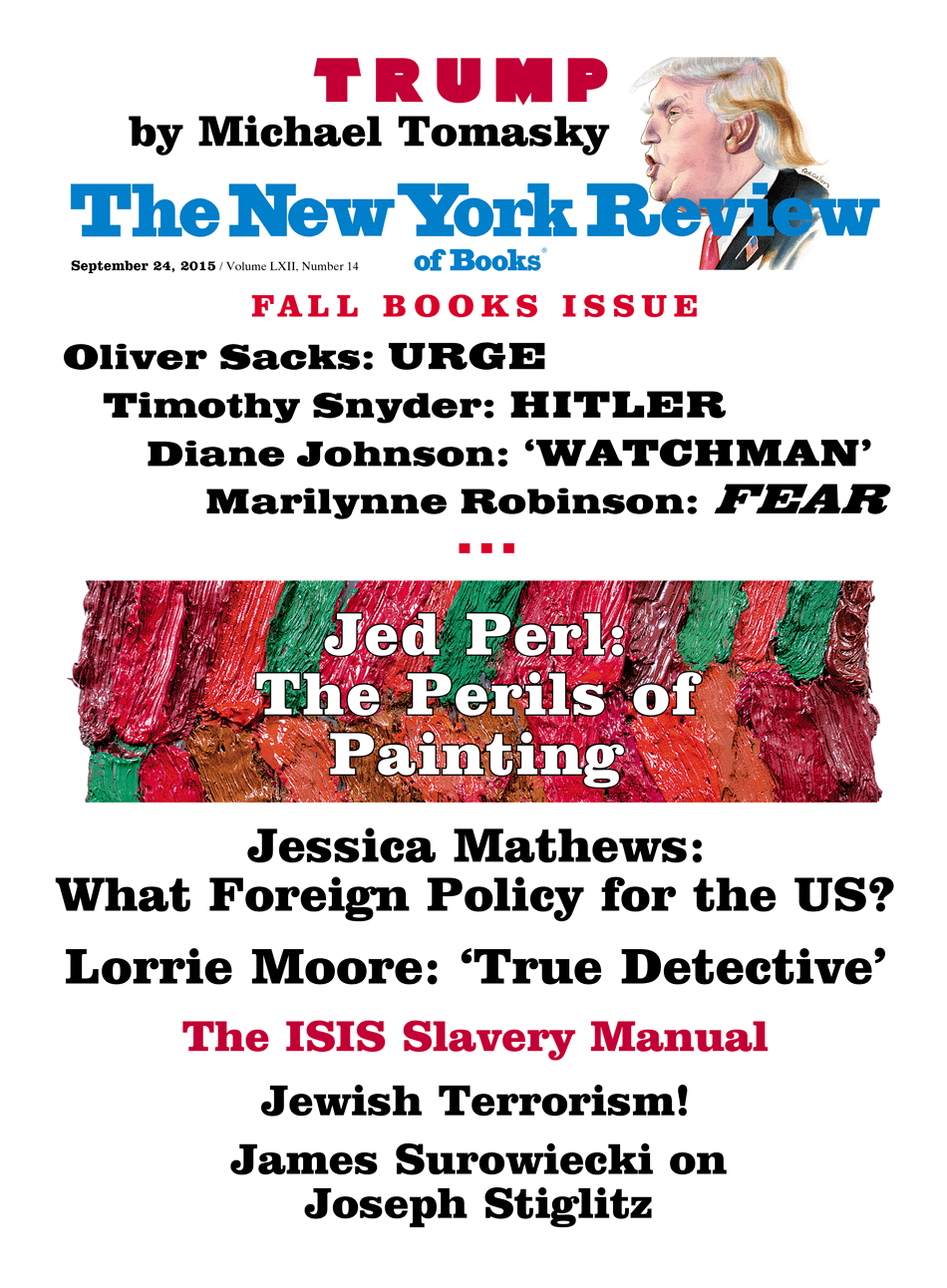

This Issue

September 24, 2015

Urge

Hitler’s World

Trump