The Mare, Mary Gaitskill’s new novel, is the story of a girl and a horse. It grapples with innocence, possibility, and hope. It is about what happens after all her other books.

Gaitskill achieved literary notoriety with Bad Behavior, her first volume of short stories, published in 1988. Her beautiful, elegant prose about ugly and inelegant sex, as well as her insistent vision of the inevitable self-destructive distance between people, gave a disturbingly detailed face to the blank carelessness of 1980s Lower East Side scummy chic. The collection made Gaitskill a downtown celebrity. She writes about sex in a casually brutal way, and in Bad Behavior and the two story collections and three novels that have followed, it is not the fetishism or violence that is shocking, it’s the way her characters experience them with almost bland neutrality.

Gaitskill’s people are obsessive and bored. They circle each other endlessly, disappointed, dulled by drugs and life yet sharply attuned to the world that failed them: runaways from disappointed suburban fathers and startled suburban mothers; strippers, prostitutes, addicts, their legs spread in New York, Paris, San Francisco, their lives useless, if not quite meaningless.

There has always been an almost wry tenderness in Gaitskill’s work, too, as if the feeling kept taking her by surprise. Veronica, her superb novel that came out in 2005, is infused with the rueful affection of a deeply damaged narrator. The Mare has four narrators, all of them hurt, but not all of them ruined: a forty-seven-year-old reformed drug and sex addict and her husband, who live in Rhinebeck, New York; a beaten-down Dominican woman in Brooklyn who beats her children; and a twelve-year-old girl, her daughter, whose name is Velveteen. She’s called Velvet.

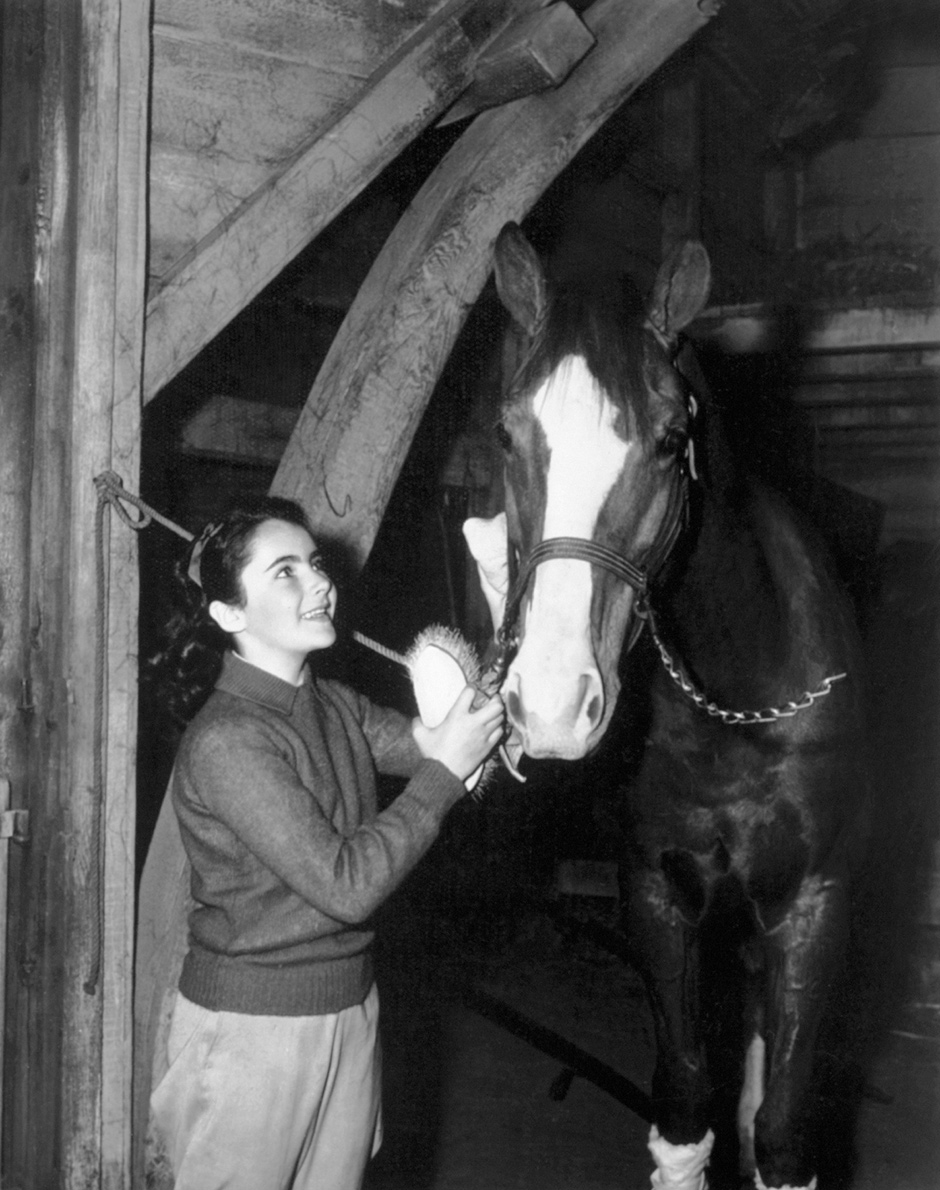

Gaitskill’s Velvet Vargas, a stubbornly independent little girl who lives in a dysfunctional family in a dead-end world, is a worthy literary descendant of Velvet Brown, the little girl in Enid Bagnold’s National Velvet. Unlike Gaitskill’s Velvet, Velvet Brown comes from a loving, stable environment. But the two Velvets share something essential: an unwillingness to be trapped. The little English girl in 1935 fought the trap of being a girl in a man’s world. For Velvet Vargas, that trap is also very real, and it is just one of many.

There is a tradition of horse stories about children, often twelve years old, often girls, that were essential reading fifty years ago when I was a twelve-year-old girl with a horse. The horse in the novels was usually wild, disobedient—no one could handle it until it bonded with the daydreamy child. The child, single-mindedly devoted and newly patient, brought out the best in the horse as the horse brought out the best in the child. The child protected the horse from those who did not recognize its nobility, and the protection of such an enormous, dangerous beast required the abstracted child to become more serious, more responsible—to grow up. But at the heart of these novels of headstrong horses and girls and boys was neither safety nor responsibility. Novels like Bagnold’s National Velvet endowed children with what was normally reserved exclusively for adults: freedom and power.

Gaitskill embraces without reservation the tradition of the love between misunderstood horse and misunderstood child, then lets it loose in a modern, racially fraught world of gangbangers and domestic abuse. In The Mare, not just horses and girls, but also mothers and the childless are all world-weary females, abused, exhausted by life, united in their desire for safety, love, freedom, and power. Gaitskill’s novel is not a children’s book, but it is a book about what children long for, and how we long for the same thing many years after we’ve left childhood behind.

Velvet’s mother is from the Dominican Republic, an angry, brutal woman who sits “in her body like it was a tank…alone in her tank, bored like a fighter…when there is no fight.” One of the characters notes that when Velvet talked about her mother “there was something in her voice that made me think of a shadow on the wall in a horror movie.” Mrs. Vargas screams incessantly at both of her children and beats them, but most of her anger is aimed at Velvet. In between rages, she coddles her six-year-old son, Dante, a kind of comic nightmare version of Donald, Bagnold’s purely comic spirit, the indomitable little brother who darts in and out of National Velvet collecting bottles of his own spit.

Mrs. Vargas’s husband left years ago. She works hard as a home health care attendant. The Brooklyn neighborhood she and her children live in is turbulent and poor. Velvet describes it in her observant, forbearing way as a mixture of geniality and inevitable violence:

Advertisement

It was so early there was nobody on the street except a raggedy man creeping against a building down below us, holding on to it with one hand like for balance. He was holding the wall where somebody had written “Cookie” in big red paint. That was because this boy called Cookie used to stand there a lot. He was called that because he ate big cookies all the time. We used to see him in Mr. Nelson’s store downstairs and we weren’t supposed to talk to him because he was from the project over on Troy Avenue. But I did talk to him and he was nice. Even if he told me once that even though he liked me, if somebody paid him enough, he’d kill me. He wouldn’t want to because I was gonna grow up fine, but he’d have to. He said it like he was making friends with me.

In Rhinebeck, a very different kind of place, Ginger Roberts lives with her husband, Paul, whom she met at Alcoholics Anonymous. She married late, she tells us, “after stumbling through a series of crappy relationships and an intense half-life as an artist visible only in Lower Manhattan, the other half of my life being sloppily given over to alcohol and drugs.” Sober now for years, she refers to her earlier existence, so much like the world of Gaitskill’s earlier work, as her “dull little hell”:

Friendship was bad, sex was worse, and love—love! That was someone who rang my doorbell at three a.m. and I would let him in so he could tell me I was worthless, hit me, fuck me…. It was not pleasure, it was like a brick wall that a giant hand smashed me against again and again, and it was like the most powerful drug in the world.

AA has given that world a diagnosis: sex addiction, addiction to extreme emotion. Her old life is not a state she wants to return to. But now, married and living in a pleasant town in the beautiful, calm countryside, she finds herself watching the mothers around her with their children and she feels separate, left out, and lonely.

She thinks of her own mother, though their relationship was far from ideal, and she imagines her mother’s “warm arms, her unthinking, uncritical limbs that lifted and held us.” The desire for unthinking, uncritical love, for a mother’s love to give and receive, is strong in this book, though Ginger still finds it necessary to reassure herself that “love is not always a sickness.”

Investigating a summer program for inner-city kids to come and stay with families in the country, Ginger sees a booklet with photographs of smiling white and black children holding flowers, white adults hugging black children,

and a slender black girl touching a woolly white sheep. It was sentimental and flattering to white vanity and manipulative as hell. It was also irresistible. It made you think the beautiful sentiments you pretend to believe in really might be true.

Velvet, shown the same booklet by family services in Brooklyn, sees “a woman with big white legs sitting in a chair with a hat on and a plastic orange flower in her hand, looking like she was waiting for somebody to have fun with.” When the social worker tells the Vargas children that they can stay with people just like this, Dante responds, “It sounds like hell,” after which his mother calls him stupid and hits him on the head. And so, Velvet observes in her unerring way, “going to this place with bicycles and sheep had been turned into a punishment.”

Gaitskill notes the vanity of the white host families, their excruciating condescension and entitlement. “They come up and they see this big house and all these nice things, and they want to know, How do you get all this?” Velvet hears one white woman say. “And I say to them, We get it with hard work.” Ginger, on the other hand, is far more needy than patronizing. The moment she sees Velvet get off the bus, she falls in love with the girl. The twelve-year-old is lovely, but it is not only the beauty of her heavy lashes or her gentle forehead that touches Ginger. Velveteen Vargas has “a purity of expression that stunned my heart.”

Where Ginger sees purity, however, Velvet’s mother sees bad blood. Bad blood is her refrain, a refrain Velvet cannot escape:

You’re no good, said some words in my head. It’s your blood that’s bad. These are words I hear a lot. I don’t really hear a voice saying them. It’s more like I feel them in my brain. Over and over. When that happens, I try to listen to the people around me to drown them out.

The accusation has made Velvet observant in order to drown out the voice inside her; it’s made her thoughtful in order to drown out the voices outside. Gaitskill’s characters tend to be exquisitely self-aware and blindly impulsive at the same time. Velvet is, too, but perhaps because the grinding degradation she sees around her is not a situation she has chosen, she is a sympathetic character in a more visceral way than Gaitskill’s runaways or edgy downtown denizens could be. Gaitskill also allows her great charm. She is as complex and changeable as any of Gaitskill’s characters; she is as needy and as battered; but Gaitskill treats her with admiration rather than irony or resignation, and she allows Velvet to respect herself. It is a very generous depiction.

Advertisement

The bad blood Mrs. Vargas is so angry about originates with Velvet’s father, a man her mother loved and trusted, who deserted her when she was pregnant with Velvet. Mrs. Vargas sees his cruelty and betrayal in everything the girl does. Bad blood—the inevitability of inherited evil, the inescapable culpability of the wrong pedigree—is another familiar trope of my girlhood horse novels, so many of which were about ancestry and breeding. For some of the horses, that ancestry was their glory. For others, it was a condemnation. In the 1940s trilogy by Mary O’Hara (My Friend Flicka, Thunderhead, and Green Grass of Wyoming), the question of whether the wild throwbacks can escape their ancestry is urgent and central to the novels in much the way it is in The Mare. The fusion of Velvet’s “purity of spirit” and “bad blood” is as heroic as any wild white stallion. But this is not an adventure tale of a stallion running free across the wide, perilous plains; it’s a different kind of adventure and the dangers are not snowstorms or birds of prey, but the perils faced by girls and women, mothers and daughters. It is no accident that Velvet’s horse is a mare.

The horse is called Fugly Girl by the girls who hang around at the stable because of her scars and her vicious temperament. The stable is down a path from Ginger and Paul’s house. When Ginger walks Velvet there on the first day she comes to stay with them, Velvet is overwhelmed by so much grass and so many trees. Even the barn looks strange to her, a building with a dark hole in its side. She is introduced to the trainers and stares at her feet uncomfortably. “Suddenly there was this loud, mad-pissed-off banging, and I heard a horse making angry wanting noises.” It is Fugly Girl, the mare who kicks and bites, who has been cruelly beaten and scarred by a previous owner. No one can come near her. But she and Velvet bond almost immediately. “I could see her think in the dark part of her eye. The white part got softer…. The wonderful horse came up to me. I put my hand out to her. She touched it with her mouth.”

Velvet and Fugly Girl immediately recognize each other’s suffering; they trust each other’s anguish. On a later secret nighttime visit to the barn, Velvet says,

She whinnied and spun in a circle, and bucked, her jerking darkness like my mother’s fists when she was so mad she’d walk up and down just beating at the air. The hate had gone out of her. Now it was just the something else. It was just me in the dark and her hard, jumping body making pain in the air.

I CAN’T GET OUT…. I thought of lying in the bed in the foster home where they put us that time my mom beat me with a belt and it got infected and I showed the social worker and they took us, me to a place in New York and Dante to New Jersey. I NEED TO GET OUT. I lay on the bed in the dark listening to girls laughing at me because I threw up the lady’s dinner as soon as I ate it…. The smell of air freshener was making me want to vomit again. But I didn’t and I didn’t cry either. Because half of me was there and the other half was nowhere and you can’t cry in nowhere.

Fugly Girl was quiet now…. She was listening to me crying.

Ginger convinces her husband that Velvet should stay longer, and even when the summer is over, Velvet comes up on weekends and rides the mare. The relationship between Ginger and Velvet sidesteps and sidles, stumbles backward and forward over the next year as Ginger’s marriage begins to fall apart and Velvet slips into adolescence. Velvet falls in love with a much older boy, a boy caught up in the ubiquitous gang violence of the neighborhood. Dominic, a powerful, strutting presence on the street, is disarming, gentle, instinctively protective toward Velvet. Attracted to her, he says, “‘How old are you?’ And I told him and his face jumped back.”

Once Dominic enters her consciousness, Velvet’s interest in Ginger, even her love of the mare, gives way to a new kind of daydream. Adolescent social disasters confront Velvet, too, toxic and humiliating. Her friends are now a catty group of girls, many of them older, who trick Velvet, still only twelve, into sneaking out to what turns out to be a dangerous drug-fueled party. When she gets home, she is met by her mother at the door:

She crushed her whole body against me, even her head bone crushed on mine. She didn’t yell. She didn’t hit. She said very soft that I wasn’t worth hitting because if she hit me now she wouldn’t be able to stop and then the police would come back and see and they’d take Dante away…. She whispered, “I could kill you right now….”

I said, “Mami, I’m sorry. I love you.” I looked in her eyes. “I love you.”

She jerked back her head like I was a snake that bit her…. And she put one foot behind my leg and then…pushed me down, held me down…. And she pushed her whole body weight on her foot, pressing into my chest…. “You’ll sleep here tonight. On the floor like a dog. If I get up and you’re not here on the floor, I’ll come get you, and I’ll put you back down until you stay there.”

Throughout the novel Gaitskill scatters darkly comic scenes that are overheard, secondhand, oblique: the white ladies at the bus station, the screams between Velvet and her mother that come through the phone while Ginger waits for Velvet to get back on the line, Dante’s colorful and cutting asides. (“Those people weird,” he says about Paul and Ginger. “That ugly man and that lady like a cat food and sugar sandwich.”) But this is a direct, straightforward novel, in which many scenes hurtle toward the reader with startling impact. When Velvet sees Beverly, a callous trainer, harshly whipping a confused and screaming horse, she tries to distract her by galloping out bareback on the unmanageable mare:

[She] took off almost out from under me…. The trees came at me with black claw-arms and rushed away, green leaves and rotting fruit…. Everything was flying past…. I saw nothing but sky that went forever until I slammed down on my back so hard my head bounced. The sky blurred and black came in on the edges…. The sky was like the ocean, full of things I couldn’t see. Birds flew, hunting for invisible things to kill. People said this was beautiful, but it was not. It would kill you if you were alone in it and I was alone. I was alone everywhere. There was nothing to stand on, nothing to hold. My mother wouldn’t even hit me because I wasn’t worth it.

Gaitskill has not lost her gift for transforming the outside world into the particular vision of one of her characters, rich and perplexed, and The Mare ripples with internal emotional movement, but it is also a physical novel. The plot is fairly predictable—a girl and her horse, two women struggling over her loyalty, the joys and horrors of turning from a child into a sexual being—there are no surprises there, except perhaps that Gaitskill chose such traditional material. But the book is an exciting read. Nothing stands still, not the horses, not the violent mother or the would-be mother, not the vicious jealous friends, not the boyfriend or husband, not the sky. Lying on the floor, kicked like a dog by her mother, Velvet remembers a horse slamming through an electric fence to get to another horse:

Her body tight like a cat going through a little hole. It must’ve hurt like hell, but she got through and ran, ran with Nova and nobody could stop them…. I thought, The horses have what the people here have. They get beat down and locked up but still, when they run, nobody can stop them.