It is the season, we are told, of the outsider. The people are fed up with politics and politicians and both parties (usually enunciated “both parties,” lest the talking head in question be thought to mean only the Republicans, thus laying herself open to charges of liberal bias). Just look at how the establishment candidates are floundering.1 It’s the outsiders and nonpoliticians who are thriving. This proves that…well, that people are sick of the status quo and the dysfunction and want someone who can shake the system to its roots, or something.

Certainly, there is some truth to this, especially on the Republican side, where the three candidates who’ve never held office—Donald Trump, Ben Carson, and Carly Fiorina—have for some time now combined for more than 50 percent in most polls. And on the Democratic side, Bernie Sanders now clearly presents a far more potent challenge to Hillary Clinton than most people thought he would three months ago. But like most pieces of Beltway conventional wisdom, this observation is a bit on the superficial side. Lumping Sanders together with Trump, Carson, and Fiorina obscures an important distinction between them, and between the liberal and conservative voters backing them and the nature of each group’s dissatisfaction with business as usual.

Sanders is not an outsider in the same sense that the three Republicans are. He has served in Congress since 1990. A man who’s been an elected representative for a quarter-century and who first ran for the Senate in 1972 can’t quite be thought of as an outsider, even if he is a socialist. Sanders, who also spent the 1980s as mayor of Burlington and ran unsuccessfully for governor two times, is a professional politician and has been for most of his adult life. The Republican troika, in contrast, truly are political neophytes—none has even run for office before, with the exception of Fiorina’s unsuccessful 2010 race for the Senate in California, when Barbara Boxer trounced her by ten points.

This distinction makes the point. When Sanders’s loyalists celebrate his outsiderness, they are celebrating his ideology. His statements are often outside mainstream political thinking and he makes utterly no apology about it. This is what they love about him. They love the blunt talk, delivered in that serrated Brooklyn accent that nearly a half-century spent living in Vermont has somehow done nothing to dull. But it’s his positions that have made him a contender in this race.

On the right, however, the allure is much more firmly rooted in the candidates’ biographies. What makes Trump, Carson, and Fiorina attractive to Republican voters is not chiefly their positions. Indeed, Trump rose to the top of the polls precisely while various media outlets were reporting that he believed Bill Clinton to be the best recent president and that he’d once supported national health care, among other apostasies. Carson rose while little was known about his views—the main things conservative voters knew were that he was a good Christian man (he’s the author of several books that have done brisk business in Christian bookstores in recent years) and he’d once criticized Obama’s philosophy and policies with the president himself sitting next to the podium.2 Fiorina’s ascent has been a function of her performances in the first two debates—emphasis on “performance,” which is to say, she made an impression by speaking in crisp and authoritative complete sentences that appeared to convey a greater knowledge of policy than most observers probably assumed she possessed.

They have two qualities in common. First, none is a Republican elected official, which means that none is to blame for what conservatives see as the GOP’s constant capitulations to the Obama agenda. Second, all of them have made the kind of personal impression that conservatives appear to be looking for this time around. They present themselves as sworn foes of liberalism, political correctness, immigration, Obama, and compromise.

People on the left believe that systems are corrupt. People on the right tend to believe that the system (at least as they understand its design) is just fine, and it’s individual people who are too corrupt or too weak to propel it toward its full greatness. Thus partisans of the right lean more toward a version of Thomas Carlyle’s view that history is about great men (and now women, too), which elevates biography to the level of supreme importance, while partisans of the left care less about the outsider’s life story than his criticism of power and how he will challenge it. These differing conceptions dictate how the candidates present themselves and even how they would govern, should one of them become president.

Advertisement

In 1997, about halfway through Sanders’s sixteen-year term of service in the House of Representatives, he published Outsider in the House, his political memoir of what it was like to be a man of the independent left operating within the two-party system. It has now been reissued, with a new preface by the author and a long afterword contributed by the Nation writer John Nichols, and renamed Outsider in the White House.

True to expectations, although the book is obviously biographical in the sense that it covers the sweep of Sanders’s career, it contains almost nothing in the way of personal reflection or revelation—indeed, one can learn far more about Sanders’s life from simply scanning his Wikipedia entry than from reading this nearly 350-page book. Such matters are, for Sanders, irrelevant to the important business at hand. Thus he opens the new preface by writing:

When people say I am too serious, I take it as a compliment. I have always understood politics as a serious endeavor, involving the fates of nations, ideals and human beings who cannot afford to be pawns in a game.

There is perhaps a page or so of personal material. We learn that his father was a Polish Jew but not that his family was killed in the Holocaust, which The New York Times has reported. We are told that his father was a paint salesman. “There was always enough money to put food on the table and to buy a few extras,” he writes, “but never enough to fulfill my mother’s dream of moving out of our three-and-a-half room apartment and into a home of our own.” We learn that after one year at Brooklyn College, he went off to the University of Chicago, although there is no explanation of how or why Chicago beckoned. He has said that he spent much of his time there reading in the library and that he was involved in the civil rights and peace movements at the university. He never even discusses why he moved to and decided to settle in Vermont.

His second and current marriage came late in life, at age forty-six, when he was in his fourth and final term as Burlington’s mayor. He has precious little to say about Jane—there’s a mention of the fact that she headed up Burlington’s Youth Office early in his tenure, but not a word about why he took a shine to her. Even when she is hauled into the narrative it is chiefly to make ideological points: that the marriage ceremony was held in an appropriately proletarian public park on Lake Champlain and that the couple honeymooned in the USSR—Yaroslavl, specifically, in order for the mayor of Burlington to perform the side duty of cementing its sister-city relationship with this city on the Volga northeast of Moscow. “Trust me,” he writes, “It was a very strange honeymoon.” (In some ways, Sanders seems to have spoken more on foreign policy matters as mayor than he has as senator or, currently, as candidate for president.)

Instead, the book focuses in deep detail on Sanders’s political career, with great emphasis, at least in the book’s earlier chapters, on his campaigns. There is for example far more detail than any but the most devoted Sandersite could want on his 1996 campaign for reelection to Congress. This was the one election when conservatives found a promising Republican candidate, Susan Sweetser, and thought they could take him out. A number of high-profile Republicans came in to campaign for her, large organizations like the National Association of Manufacturers put money into beating him, and the National Rifle Association had him in its sights. In the end, he won in a landslide. He’s never had a race since that was remotely close.

The chapter on his tenure as Burlington mayor has more substance. He won his first mayoral election, in 1981, by just ten votes out of about 8,600 cast. The 1980s was the decade, as the writer Bill Bishop has put it, when “the big sort” started in America—when we started clustering with like-minded fellow citizens, in the formative stages of dividing ourselves into red and blue America. Thus the decade of Sanders’s mayoralty was also the decade when Vermont was transforming itself from an agrarian Republican stronghold into the hippie–yuppie–Ben & Jerry’s paradise it has become.3 The Burlington of 1981 wasn’t quite ready for a self- described socialist in City Hall, so at first, Sanders was up against it:

On the day that the mayor formally announces his choices for administration posts, the Board [of Aldermen] rejected all of my appointees. The situation was absurd: I was expected to run city government with the administration of the guy I had just defeated in a bitter election, and a group of people who vigorously opposed my political goals. We were outflanked by the opposition on every major decision. The votes were always the same: eleven to two, the eight Democrats and three Republicans on one side, Terry and Sadie on the other.

But Sanders did what a good politician does: he out-organized the competition. He and his allies captured some aldermanic seats in the next by-election, and now, “the people had spoken loudly and clearly.” His appointments were accepted this time, and he got to work, governing somewhat unpredictably. He kept property taxes flat (while raising corporate taxes). He hired a sharp comptroller and saved taxpayers money. He expanded the police department. He brought in a minor-league baseball team—amusingly enough, the Vermont Reds, although the name had nothing to do with politics (they were the AA franchise of the Cincinnati Reds).

Advertisement

If Sanders was ever a true socialist in the sense of wanting the state to own the means of production, he doesn’t say so outright. Rather, he seems always to have been a person with left politics and a distaste for the two-party system; and because Vermont had historically had a comparatively weak Democratic Party, there was room for him to compete electorally as a candidate of the independent left that did not exist in states where the Democrats maintained a stronger presence. But ideologically, his program, then and now, is not terribly different from that of most economically left-populist Democrats, from Elizabeth Warren to Harry Truman.

So, as mayor, he pushed a number of projects in keeping with that perspective. He expanded affordable housing, passed tenants’ rights legislation (but lost on rent control), and visited Nicaragua as an invited guest of honor on the occasion of the Sandinistas’ seventh anniversary in power. He lost a race for Congress in 1988 to a moderate Republican but came back two years later to beat the incumbent, Peter Smith, by sixteen points.

The book ends in 1997, so the events Sanders is writing about are all rather distant at this point, but his concerns and positions have not changed: the moneyed interests have taken over the political process, the system is unresponsive to regular people, and the country needs a fundamental and thoroughgoing change in economic priorities.

He is certainly a man who has found his moment. The enthusiasm he’s sparked has stunned many observers, and no doubt even Sanders himself—he has drawn crowds in excess of 20,000 more than once, an astonishing number to come out to see a political speech. He has also raised a staggering amount of money for someone who neither seeks nor is offered large contributions from corporations and their executives. He raised $26 million in the third quarter of 2015, which was only $2 million less than Hillary Clinton. The polls all reflect it—he has been slowly closing in on Clinton in the national surveys. She can’t shake her e-mail woes, and he leads her in New Hampshire, which will hold the first primary next year (and the second contest, after the caucuses in Iowa, where Sanders has also led Clinton in some polls).

The issues that have so far dominated the campaign are exactly the ones that have been Sanders’s bread and butter for decades. Clinton has adopted many Sanders-like positions on issues such as controlling the cost of higher education and strengthening the Dodd-Frank banking regulations. But many liberal Democrats don’t trust her, given her more centrist past. And she simply doesn’t have Sanders’s instinct for going after the ruling class in a way that satisfies the anger of the left-leaning base.

In mid-September, I wrote a column for The Daily Beast comparing the two candidates’ reactions to the results of the August referendum in Greece, when voters rejected austerity measures.4 I have encountered nothing that better conveys the difference between the candidates’ world views. Clinton said:

I think it is imperative that there be an agreement worked out with Greece. And I urge the Europeans to exert every effort to find one. Greece is a NATO ally, it is a member of the European Union. The United States has a great, active, successful Greek-American community. So I want to see a resolution.

Sanders said:

I applaud the people of Greece for saying “no” to more austerity for the poor, the children, the sick and the elderly. In a world of massive wealth and income inequality, Europe must support Greece’s efforts to build an economy which creates more jobs and income, not more unemployment and suffering.

Notice how Clinton is speaking to the people holding power, urging them to be reasonable, while Sanders is speaking to the powerless, urging them to press on with the fight. Small wonder that Sanders is the one connecting.

The question that looms over the Sanders campaign, though, is where he goes after New Hampshire. Even if he wins both it and Iowa, the calendar afterward wouldn’t appear friendly to him. Nevada and South Carolina are states where, respectively, the Latino and African-American votes will loom large, and Clinton has far deeper reach into those communities than does Sanders, who comes from a state that is 95 percent white and just 1 percent black.

Then, on March 1, comes Super Tuesday, which consists mostly of southern states. A Democratic primary in those states will concentrate on black voters, trial lawyers, teachers, other public employees—all Clinton constituencies to a significant degree. (Joe Biden, if he decides to run, can probably put up more of a challenge to Clinton among these groups than Sanders can.) Barring unusual circumstances, it’s difficult to see how Sanders could amass the delegates needed to win the nomination.

But remember that in 1992, against Clinton’s husband, insurgent candidate Jerry Brown lasted into April as an active campaigner, and even then did not withdraw and back the Clinton-Gore ticket. Instead he seconded his own nomination at the convention. Sanders seems to have a strong personal confidence in his message. He could at the very least campaign deep into the spring and collect enough delegates that the Democratic winner would have to respect him and his positions. This is why it was smart of him to run as a Democrat instead of as a third-party candidate: he has potentially much more power this way.

Nothing in this campaign has been more improbable than the rise of Ben Carson. In the spring, he was at 2 percent. As I write these words, he runs second to Trump and is closing in on him. Why?

Carson’s appeal would seem to be almost exclusively about his biography. It begins, frankly, with his race—conservative voters love to have a chance to show the liberal media that they aren’t racist by supporting a black candidate. Beyond that, his life story is remarkable. As has often been written, he grew up poor in Detroit. But there was much more to it than that. When Carson was eight, his mother discovered that his father had a second family. He moved out, with the expected grim economic consequences for Mrs. Carson and her two boys. Then, every so often, his mother would go away, she said, to visit relatives. It was only as an adult that he learned, he writes in Gifted Hands, that “when the load became too heavy, she checked herself into a mental institution.”

He showed promise, worked hard, and decided early on that he wanted to be a doctor. He got into Yale. The pivotal moment in his life came when he felt sure he was about to flunk a chemistry final, which would mean he could not enter medical school. He prayed for God’s help. He went to bed petrified. Then he had a dream. He was sitting in a classroom in this dream, when “a nebulous figure” walked in and started writing chemistry problems on the blackboard. When Carson awoke, he quickly put pen to paper to write them all down. What happened next, when he showed up for the examination?

I felt I had entered that never-never land. Hurriedly, I skimmed through the booklet, laughing silently, confirming what I suddenly knew. The exam problems were identical to those written by the shadowy dream figure in my sleep.

Stories like this, whatever we may think of them, are staples of inspirational books that sell by the millions in this county and fill hours and hours of time on Christian radio and television. It’s no wonder that Carson became something of a celebrity in conservative Christian circles long before he decided to embark on a political career. In 2009, Gifted Hands was made into a TV movie as a Johnson & Johnson Spotlight Presentation, a series offering mostly inspirational stories, starring a bona fide Oscar winner, Cuba Gooding Jr.

Carson became justifiably famous as a pediatric neurosurgeon. His most renowned triumph—and he tells the story grippingly—was his successful separation of German conjoined twins in 1987 when they were just seven months old.5 It’s hard to believe that a man who could show such profound humanity in treating patients could be such a raging reactionary in his politics, but he sometimes says things even Donald Trump wouldn’t say. On contemporary America:

I mean, very much like Nazi Germany. And I know you’re not supposed to say Nazi Germany, but I don’t care about political correctness. You know, you had a government using its tools to intimidate the population. We now live in a society where people are afraid to say what they actually believe.

On whether being gay is a choice:

Absolutely…. Because a lot of people who go into prison go into prison straight and when they come out, they’re gay. So did something happen while they were in there?

He apologized for this one, but without quite acknowledging that he could have been wrong.

From time to time, on the other hand, Carson has taken a few surprisingly liberal positions. He has criticized Trump’s plan to deport 11 million undocumented immigrants as impractical; in past writings, he has even spoken favorably of the Glass-Steagall Act and some form of gun control. Those haven’t come up yet in this campaign, so it will be interesting to see if, like Trump, Carson will be permitted a few eccentric departures from orthodoxy by the “base.”

My guess is that he will. Conservative voters have already decided they like him, and once voters settle on that basic question, specific annoyances are easy to rationalize away. It’s all about his biography. Here’s a doctor who by rights should have grown up to be another liberal Democrat but with God’s unexplainable guidance joined their side and even called Obama on his socialism right to his face. That’s enough to get him to 20 percent. And he may do well in Iowa, where evangelicals dominate the GOP caucuses. It probably gets harder for him after that.

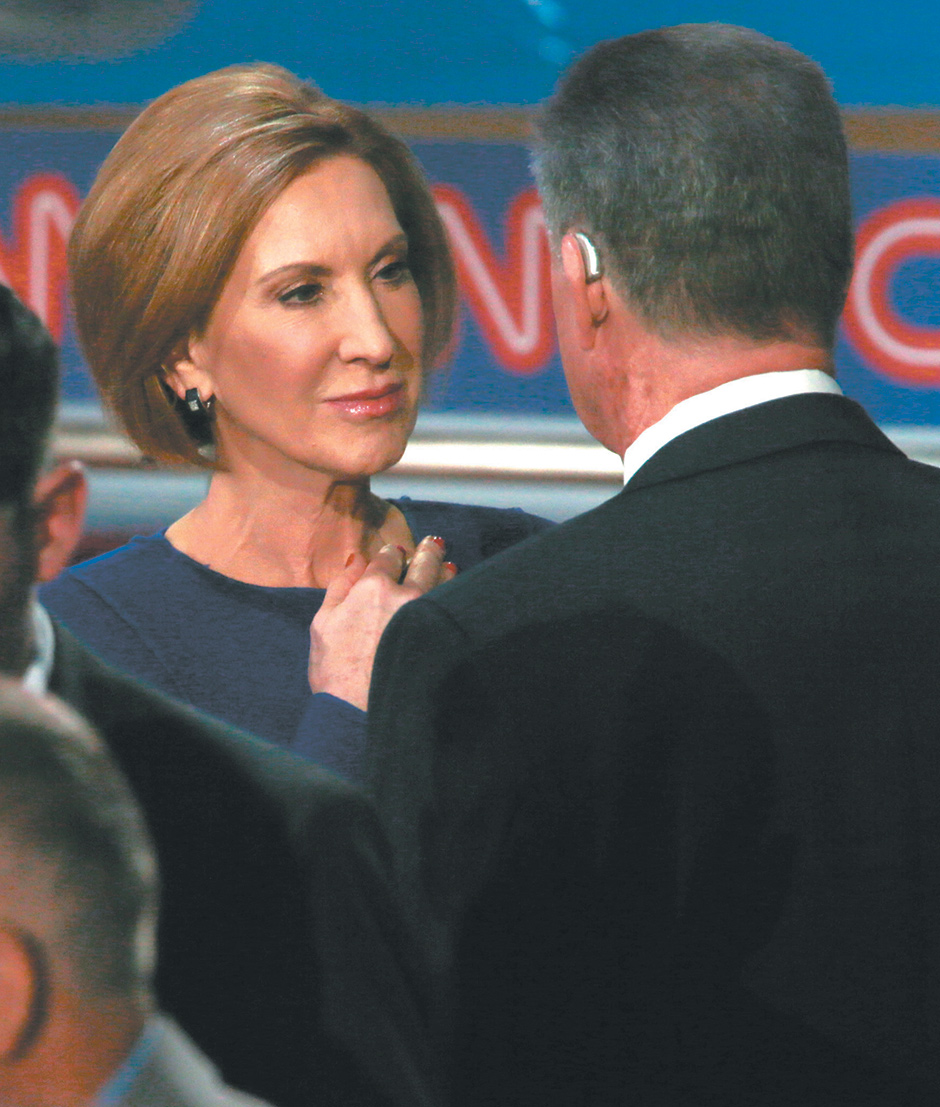

Finally, we have Carly Fiorina, also running on her biography—a risky choice in her case since, as many have pointed out, sitting at the center of her story is one of America’s more spectacular corporate failures in recent history. When she led Hewlett-Packard, she argued hard for a takeover of Compaq, which she pushed through a deeply divided board with only 51.4 percent of the vote. It turned out to be a disaster for HP. The stock price fell by half, many thousands were laid off, and yet she left with a $21 million golden parachute.

Fiorina, of course, has her own version of these events, which she retails in Rising to the Challenge and has touched on in the debates. She always notes that it was a tough time all around in the tech world from 1999 to 2005, the years of her reign as CEO, and this is true, but others have written that HP stock dropped far more dramatically than that of most of its competitors.6 She argues that she doubled revenues, but critics respond that that was chiefly a result of her company’s swallowing up another large company. She even argues in the book that accepting her firing was an act of selflessness and principle:

The truth is, I could have prevented my dismissal, but I was neither prepared to sacrifice my principles nor subject the company to a prolonged period of conflict that would have continued to play out on front pages around the world. As chairman of the board, I had a vote on every matter before the board, including my position as chairman and CEO. I chose not to exercise that right. In the end, I lost the final vote on my position by a single vote.

Elsewhere, she touches on aspects of her life that are bound to arouse sympathy. She opens the book with the story of the police coming to tell her and her husband, Frank, that thirty-five-year-old Lori, Frank’s daughter from his first marriage whom Carly had helped raise, had died of a drug overdose. There is a chapter on her breast cancer diagnosis; she underwent treatment the same year Lori died.

In those passages, she softens things up a bit. But the mode that comes much more naturally to her is blunt aggression. As with Carson’s race, Fiorina’s gender is an asset to conservative voters as they behold an apparently successful woman who has refused to be taken in by the usual feminist claptrap and who really knows how to zing those liberals. The fight she picked with Planned Parenthood at the second debate is the perfect example, when she claimed to have watched a sting video made by a conservative group that she said featured a fetus wriggling on a table after an abortion, while some callous baby-killer says, “We have to keep it alive to harvest its brain.” Less well remembered is the confrontational way she opened these comments: “I dare Hillary Clinton, Barack Obama to watch these tapes.” Pow!

As many who viewed the tapes in their entirety have noted, they include no such images or words. The charitable explanation appears to be that Fiorina might have confused these videos with some others. Whatever the reason, after numerous fact-checkers and other critics showed that what she said simply isn’t true, she and her campaign became even more insistent. NBC’s Chuck Todd asked her if she hadn’t “exaggerated” the scene. Her response: “No, not at all. That scene absolutely does exist.” To back down would constitute capitulation to the liberal elite.

Fiorina may not win all that many votes, but she will be a useful presence for her party to keep in the spotlight, especially if Clinton is the Democratic nominee. She could attack Clinton’s private e-mails and recall the death of J. Christopher Stevens in Benghazi without exposing the party to charges of sexism or misogyny, and she has shown already that she would relish being out front: “If you want to stump a Democrat,” she said in one of her rehearsed lines at the second debate, “ask them to name an accomplishment of Hillary Clinton.”7 She might be a plausible vice-presidential candidate, depending on the circumstances, as might Carson. Outsiders usually fade away as the months pass, but disgust among core Republican voters with their own leaders—witness the celebrating that occurred on the right when Speaker John Boehner announced his retirement—is such that it might be different this time.

-

1

In Jeb Bush’s case, that may be putting it mildly. A September 27 Washington Post article, headlined “It’s Make or Break Time for Jeb Bush” and sourced to “numerous senior GOP fundraisers,” reported that if Bush doesn’t show meaningful movement in opinion polls by late October, the donors who have thus far sustained his campaign will dump him. ↩

-

2

he occasion was the National Prayer Breakfast in February 2013. The video was viewed millions of times on YouTube, and The Wall Street Journal immediately wrote an editorial urging Carson to seek the presidency. ↩

-

3

A piece of astounding political trivia, given the deep-blue nature of Vermont today: Sanders’s partner in the Senate, Patrick Leahy, is the only Democrat ever elected to the Senate from the state. Going back to Lincoln’s time, the state had never elected a Democratic senator until Leahy’s first win in 1974. ↩

-

4

“What Hillary Clinton Can Learn from Corbyn,” The Daily Beast, September 15, 2015. ↩

-

5

The surgery was a success, but information about how the twins have done since is hard to come by, and Carson says little in the book, which was published three years after the procedure. ↩

-

6

See among others Steven Rattner, “Carly Fiorina Really Was That Bad,” The New York Times, September 25, 2015. ↩

-

7

Actually, Politico took her up on the question and asked twenty Democrats to do just that. They came up with answers I had never heard. For example, as a senator, she appears to have played a central part in conceiving of the Lilly Ledbetter Fair Pay Act, which was the first law President Obama signed; and as secretary of state, she led the effort to get China to agree to cut its carbon emissions. It was enough to make one wonder why the Clinton campaign hasn’t done more to promote these facts. See “What Is Hillary Clinton’s Greatest Accomplishment?,” Politico Magazine, September 17, 2015. ↩