In response to:

The Mystery of Primo Levi from the November 5, 2015 issue

To the Editors:

Tim Parks’s engaging review of The Complete Works of Primo Levi [NYR, November 5] is satisfying on a number of levels, but I was disheartened to see the piece bookended by the “suicide.” Parks’s phrase that Levi “threw himself down the stairwell to his death” is not, in any case, an accurate way to describe a tumble over a railing. But the larger issue is that thoughtful and important people close to Levi, who first thought it was a suicide, have reconsidered the event. These people include his cardiologist and friend David Mendel, his lifelong friend Nobel laureate Rita Levi Montalcini, and Fernando Camon. Levi was in a whirl of activities—he’d scheduled an interview for the following Monday, he was considering the presidency of the publishing house Einaudi, he’d just submitted a novel, and that very morning he mailed a plan-filled letter. Add to that the tight dimensions of the stairwell, a railing lower than his waist, recovery from surgery (lowered blood pressure), the number of people who survived Auschwitz and did not kill themselves, and a number of other factors, and the suicide doesn’t make sense.

It has been a useful symbol for critics and other writers to hold on to as they imagine the why and how, but it is grossly unfair to the man and to his work. If this crutch is removed, his material can be examined in fresh light—an examination that he deserves.

I hope the editors of The New York Review will help discourage the story, which, in the cycling of Internet sites, already holds a terrifically strong grip. I would strongly urge you to see this 1999 essay, “Primo Levi’s Last Moments” by Diego Gambetta.

Carolyn Lieberg

Washington, D.C.

Tim Parks replies:

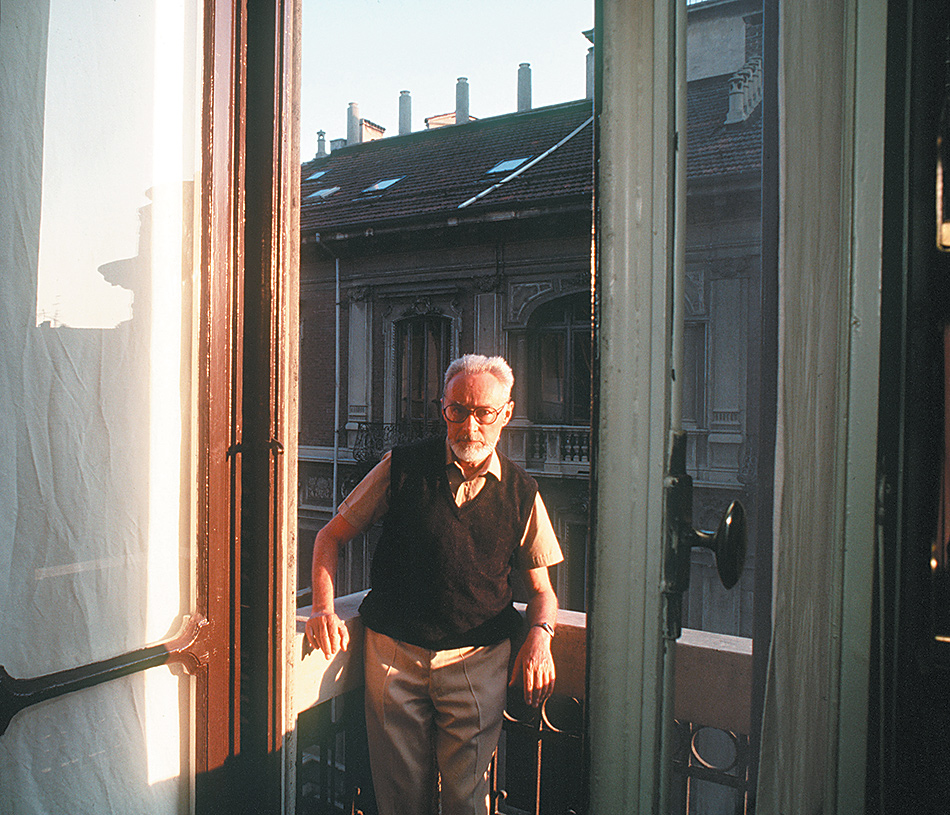

“1987—April 11: Levi dies, a suicide, in his apartment building in Turin.”

I quote not from a rogue website but from the author chronology provided in The Complete Works of Primo Levi, the book under review. These words, in turn, are a translation of the chronology prepared by Il Centro Internazionale di Studi Primo Levi in Turin, the most authoritative source of information on Levi; they were actually written by Ernesto Ferrero, for many years Levi’s editor at Einaudi, a close friend who knew the author well and spoke to him regularly right through to the end.

The three biographers—Ian Thomson, Carole Angiers, and Myriam Annissimov—who worked intensely on Levi’s life, interviewing most of those who knew him, all speak of his suicide as fact. The police on the scene concluded that the death could only have been suicide, this for the simple reason that one does not take a “tumble over a railing” in a Turin apartment block. The Turin law court that heard the evidence surrounding the death agreed and gave its verdict accordingly. In any event it is unthinkable that Levi, a cautious man, would have brought up children and maintained his infirm mother in a building where one could simply tumble over bannisters.

Diego Gambetta’s Boston Review article, to which Carolyn Lieberg refers me, is an extended exercise in wishful thinking, sometimes disingenuous (as when it claims, for example, that the biographies do not back up their claim that the death was suicide, or omits to mention the family’s immediate acceptance of the suicide verdict, or suggests that the height of the railing was abnormally low), sometimes plain wrong, as when it claims that Levi never wrote in favor of suicide. In the story “Heading West” (published in 1971, but interestingly republished shortly before the suicide in 1987), he sympathetically describes a remote tribe who refuse a drug that will put an end to an epidemic of suicides. The chief of the tribe writes, and they are the final words of the story, that the tribe’s members “prefer freedom to drugs, and death to illusion.” Freedom is always a positive word for Levi.

As early as 1959 Levi had written to his German translator, Heinz Reidt, that “suicide is an act of will, a free decision.” In 1981 when Levi’s German teacher, Hanns Engert, hanged himself, Levi was asked to sign a petition claiming it was murder. But the evidence was so overwhelming that he refused: “Hanns killed himself,” he said. “Suicide is a right we all have.”

This brings us to the moral issue at stake here. Levi was a sworn enemy of denial in all its forms. In If This Is a Man he is dismayed when at Auschwitz his friend Alberto convinces himself that his father, just “selected,” will not actually be sent to the gas chambers. It is a renunciation of reality, of sanity. Later, he would be equally dismayed that Alberto’s parents continued to deny the obvious truth that their son had died in the march away from Auschwitz, preferring to believe that he was somehow safe and well in Russia. In The Drowned and the Saved Levi attacks all attempts to find solace in pieties and “convenient truths,” in particular the notion that Auschwitz victims, himself included, were somehow sanctified by their experience, their courage and goodness becoming almost a consolation for the awfulness of what had happened: “It is disingenuous, absurd and historically false,” he writes, “to argue that a hellish system such as National Socialism sanctifies its victims.”

Advertisement

Given that Levi’s instinct was always to encourage the reader to confront the hardest of facts and not take refuge in any comfort zone, we owe it to him to acknowledge the overwhelming evidence of the way he died. His suicide does not diminish his work or his dignity. He was not obliged to his readers to behave in a reassuring way or protect the illusions they had built around his person. “In my work I have portrayed myself…as…well-balanced,” he remarked. “However, I’m not well-balanced at all. I go through long periods of imbalance.”

Whatever his reasons for doing what he did, and clearly in the last months of his life he oscillated between deep depression and rare moments of enthusiasm for new projects, Levi was a free man, exercising “a right we all have.” “He’s done what he’d always said he’d do” were reportedly his wife’s words on returning home to discover what had happened.