In December 2005, a panel of US military officers at Guantánamo Bay convened a hearing about the case of a Mauritanian prisoner named Mohamedou Ould Slahi. In the midst of the proceedings, Slahi mentioned that he had recently completed a memoir. “When it is released I advise you guys to read it,” he said. “It is a very interesting book, I think.”

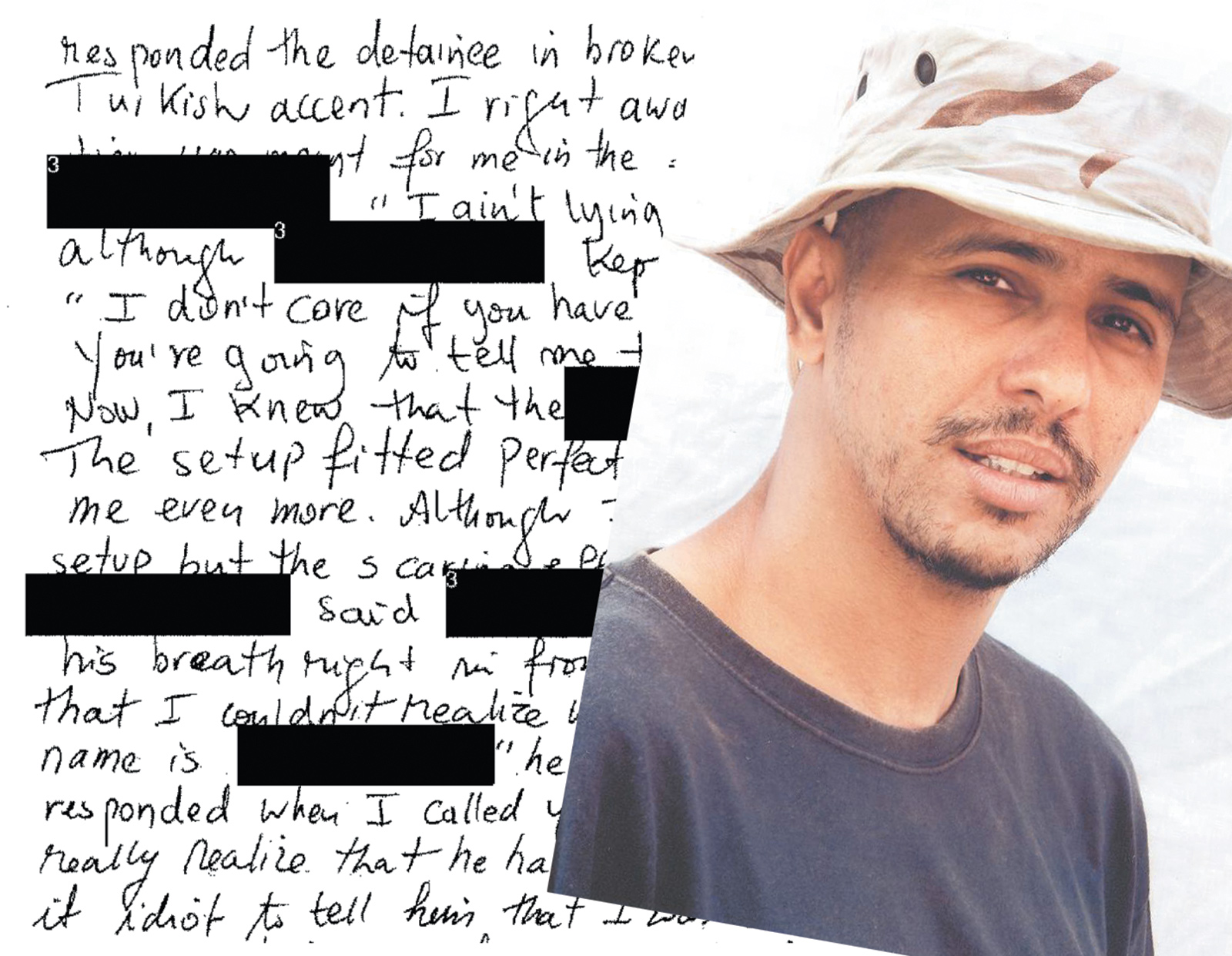

This once, an author’s generous self-assessment proves to be an understatement. It took ten years for Slahi’s lawyers, editor, and publisher to bring a version of his hand-scrawled, 466-page manuscript to the public. The volume has been carefully edited and annotated by Larry Siems, a writer and human rights researcher. Siems had to proceed without Slahi’s participation, since the author remains locked up at Guantánamo without charges or any firm prospect for release. The effort to publish Slahi’s manuscript took so long in part because the American government classified it as a state secret and sequestered it for years in a building outside Washington, D.C. The prisoner’s advocates eventually won release of a redacted, declassified text that could be shaped into this book.

The result is extraordinary. Guantánamo Diary is certainly the most important and engaging example of prison literature to have emerged so far from the misconceived Global War on Terrorism. Slahi’s voice from page to page is funny, self-deprecating, intelligent, generous, and very painful to read. He documents some of the cruelest chapters of Guantánamo’s dark history.

In 2003, he was singled out for a “special” interrogation program directly approved by Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld. The protocol was designed to break Slahi through mock executions, sleep deprivation, beatings, and sexual assaults. The torture he describes is appalling. (Senate Armed Services Committee investigators later published a report confirming the essentials of his account.1) Yet it is Slahi’s humane and resilient voice, his capacity for moral reflection, and, perhaps above all, his decision to write freely in impossible circumstances that most powerfully indict his jailors.

“I kept getting books in English that I enjoyed reading, most of them Western literature,” he recounts at one point, after his torture has ended.

I still remember one book called The Catcher in the Rye that made me laugh until my stomach hurt. It was such a funny book. I tried to keep my laughter as low as possible, pushing it down, but the guards felt something.

“Are you crying?” one of them asked.

“No, I’m alright,” I responded. It was my first unofficial laughter in the ocean of tears.

His descriptions of his American guards—torturers, mentors, spiritual seekers, chess teachers, addicted gamers—are entertaining and generous in some instances, acid in others. He is bemused to discover that “Americans worship their bodies…. I have a big variety of friends who come from all backgrounds, and I really had never heard any other group of mortals speaking about the next workout plan.” One fitness-obsessed guard “was like anybody else: he bought more food than he needed, worked out even during duty, planned to enlarge his member, played video and computer games, and was very confused when it comes to his religion.”

Remarkably, English is Slahi’s fourth language, after Arabic, French, and German. He learned it for the most part as an American prisoner, while under near-daily interrogation or during the long interludes that he shared with his guards between questioning or torture sessions. (“When it comes to spelling, English is a terrible language,” he notes. “I don’t know any other language that writes Colonel and pronounces it Kernal…. On top of that, prepositions in English don’t make any sense; you just have to memorize them.”) Siems has edited the original text so that Slahi’s verbs agree, but the prisoner’s wit would be apparent in any grammar: “I learned that there was no way to speak colloquial English without F ing this and F ing that.” As a faithful Muslim, “I had a problem when it comes to blasphemy, but everything else was tolerable. The curses are just so much more harmless when everybody uses them recklessly.”

Slahi’s gifts of empathy lie at the heart of his faculty as a writer. He mocks his interrogators’ cluelessness but then remarks on how sad it is that they have been so poorly trained. He endures beatings and sexual aggression and then sympathizes with his tormentors’ poor job prospects or their yearning for spiritual meaning. Some Guantánamo prisoners responded to their conditions by undertaking hunger strikes (as Slahi did early in his incarceration) or committing suicide. Eventually, Slahi chose to write, and by doing so, he restored his own agency and independence.

Advertisement

After the terrorist attacks in Paris, amid the climate of fear and xenophobia that has followed, and the shootings in San Bernardino, the book’s achievements seem particularly relevant. Once again, as occurred after September 11, Western governments are tempted by arguments that international terrorism requires categorical departures in the laws governing detention, surveillance, and civil rights, including the rights accorded to refugees under international law. Again, racism and prejudice threaten to conflate the entirety of Arab civilization and the Islamic faith with the brutal extremism of a small, opportunistic minority.

Slahi’s criticisms of the torture, pointless interrogation, and indefinite detention he has endured are often pitched as arguments that his jailors should know better—he is sometimes hard-pressed to believe that such a powerful nation as the United States can act so stupidly. His account reminds us pointedly that brutal interrogation produces false confessions and wasted effort. Also, depriving prisoners of due process, humane treatment, and fair trials only deepens their convictions—and those of their families, clans, and countrymen—that Western claims to global leadership in human rights and the rule of law are false and hypocritical. Slahi writes:

Like me, every detainee I know thought when he arrived in Cuba it would be a typical interrogation, and after interrogation he would be charged and sent to court, and the court would decide whether he is guilty or not…. It made sense to everybody: the interrogators told us this is how it would go and we said, “Let’s do it.” But it turned out either the interrogators deliberately lied…or the government lied to the interrogators.

Yet his tone is rarely polemical. Toward the end of his narrative, he asks, “So has the American democracy passed the test it was subjected to with the 2001 terrorist attacks? I leave this judgment to the reader.” By this point in his narrative, no further argument is required.

Slahi is one of 107 prisoners who remain at Guantánamo almost fourteen years after the facility opened in January 2002. Since its opening, 775 prisoners have been brought there. The memoirist belongs to a group of prisoners currently numbering forty-nine who have never been charged with a crime and are still being held indefinitely. (Another group of similar size has been cleared for release. Those prisoners are being held until a secure destination can be identified. A handful of other detainees have been selected to face trials before military commissions.)

During his seven years in office, Obama has reduced Guantánamo’s population by half, but his work to close the prison has sometimes seemed halfhearted, and in any event, legislative restrictions imposed by the Republican majority in Congress make it unlikely that the president will be able to keep his promise to close it before he leaves the White House. The Republican opposition to shutting Guantánamo is more politically opportunistic than principled. George W. Bush declared during his second term that he would like to close the prison, yet today the resisters in his party argue that accused terrorists are too dangerous to hold on US soil, a dubious concern given that many hundreds of convicted murderers and terrorists are securely incarcerated in state, federal, and military prisons across the United States.

Some years ago, it was possible to think of Guantánamo as a profound but short-lived error, one that would soon be consigned to history. No longer. The prison has evolved into a durable symbol of America’s broken and demagogic politics, and a dehumanizing limbo. To run the prison, the US Navy makes arrangements with for-profit private companies for multiyear operations and supply contracts. The Pentagon promises speedy reviews for inmates in limbo like Slahi but it has failed to deliver. So far as is known, the systematic torture of prisoners at Guantánamo has ended, if one does not count the occasional force-feeding of hunger strikers as abuse. Instead, Guantánamo has sunk into bureaucratized torpor, a place where the clocks tick very slowly. This is the setting for Guantánamo Diary’s appearance. Like a message in a bottle, it has landed on American shores ten years after it was written, a plea for recognition from one prisoner on behalf of many others.

Mohamedou Ould Slahi’s story is an odyssey of the age of transnational counterterrorism. He grew up in Nouakchott, the capital of Mauritania, on the West African coast. His father dealt in camels. As a boy, Slahi memorized the Koran. He also studied mathematics and won a scholarship to Germany. He flew there in 1988. In Duisburg, he learned German and then enrolled at the local university, to study electrical engineering.

By Slahi’s admission, he traveled to Afghanistan several times during his college years, during the early 1990s, to volunteer with other Arab outsiders as a fighter on the anti-Communist side of the Afghan civil war. Al-Qaeda was a principal organizer of such international volunteerism at the time. Slahi swore allegiance to Osama bin Laden and fought in a mortar unit in the battle to take Gardez, a town in eastern Afghanistan, in 1992. As the Afghan war descended into ethnic fratricide among Islamist guerrilla factions, Slahi returned to his university in Germany, and graduated in 1995.

Advertisement

Beyond these facts, the evidence about Slahi’s involvement in militancy and jihadi violence remains murky and disputed. Slahi’s position in court filings is that his involvement with al-Qaeda ended in 1992 and that he did nothing more for the organization, although he knew some members and occasionally was in touch with them.2 The Obama administration’s position has been that there is no evidence that Slahi formally left al-Qaeda and that he had continuing contacts with active members, including a relative who was a spiritual leader of the group and two important members of the September 11 plot who once spent a night at his apartment in Germany. Yet the American government has never charged Slahi with a crime or presented evidence that he participated in violence after he left Afghanistan more than two decades ago. In Guantánamo Diary, Slahi insists that he knew nothing of al-Qaeda’s terrorism in the West and had no part in it.

By 2001, Slahi was nonetheless under surveillance and had been questioned by police. He moved from Germany to Canada, and then returned to Nouakchott. In November 2001, Slahi was married and working at a local electronics company, enjoying what, in Mauritania, were middle-class comforts. That month, at the request of the United States, his government arrested him and held him for seven days. It then informed him that he would be transferred without charges to Jordan for additional interrogation, on suspicion that he had participated in violent plots against Jordanian targets while he was in Canada.

For the United States at this time, reeling from September 11 and possessing little firm intelligence about al-Qaeda’s inner workings, Slahi’s case was one of dozens of similar character. The Bush administration asked allied governments to detain and transfer prisoners under the policy of “extraordinary rendition.” This is a counterterrorism practice that began during the Clinton administration and has continued under Bush and Obama. Under the policy, the United States routinely transfers detainees for questioning to countries with well-documented records of torture. Slahi did not need a Human Rights Watch annual report to know what he would face at the hands of the Jordanian secret police.

A CIA plane flew him to Amman. Slahi is circumspect about all that he may have endured during eight months in Jordanian custody, where he enjoyed “The Hospitality of My Arab Brothers,” as he puts it. To and from his interrogation cell his escort “would make me pass through the torture row so I would hear the cries and moans and the shouting of the torturers.”

In July 2002, Slahi was blindfolded, loaded into a “hearse truck,” and driven to a place where he “felt the presence of new people, a silent team.” They stripped him naked and wrapped him in a diaper, and pulled him aboard a plane. He had no idea where he was flying. At first, he thought he was headed to the United States, but when the plane descended after five hours, he guessed Germany. Next he boarded a helicopter. His guards spoke a language he didn’t recognize, probably Dari. “I thought, What the heck are they speaking, maybe Filipino?” He figured he had been transferred to an American prison in the Philippines. A doctor looked him over and guards dressed him in “Afghani clothes…. My hands, moreover, were put in mittens. Now I’m ready for action! What action? No clue!”

“Where is Mullah Omar?”

“Where is Usama Bin Laden?”

“Where is Jalaluddin Haqqanni?”

Such were the shouted questions at his first American interrogation. The last Slahi knew, when he disappeared into Jordanian cells, the United States was fighting a seemingly stalemated war with the Taliban for control of Afghanistan. Now he inferred, behind his blindfold, that the Americans had taken over the country but that bin Laden and the others had escaped.

In fact, Slahi had been transferred to a prison at Bagram Air Field in Afghanistan. His initial interrogations proved to be the first of many absurdist experiences. An American guard tried to convert him to Christianity; the guard explained that he liked George W. Bush (“the true religious leader”) and hated Bill Clinton (“the Infidel”). He also “loved the dollar and hated the Euro. He had a copy of the Bible on him all the time, and whenever the opportunity arose he read me stories.”

A few weeks after Slahi arrived at Bagram, military police burst into his cell and rousted him for a long flight to Cuba, this time on a transport plane filled with other prisoners. “The detainees had reached their pain limit,” he recalled. “All I heard was moaning.” An Afghan beside him pleaded in Arabic: “Sir, how could you do this to me? Please, relieve my pain, Gentlemen!”

Slahi laughed, “not at him…at the situation. First, [the Afghan] addressed them in Arabic, which no guards understood. Second, he called them Gentlemen, which they were most certainly not.”

He arrived at Guantánamo at a time when the Pentagon had decided to make systematic use of torture, in parallel to the CIA’s adoption of waterboarding, sleep deprivation, and other harsh methods in its own secret prisons. Major-General Geoffrey Miller commanded Joint Task Force–Guantánamo, the unit that would carry out the most brutal protocols. In January 2003, according to a later Senate Armed Services Report, a memo proposed a special plan for Slahi that included twenty-hour interrogation sessions, the use of dogs, denying him the right to pray, sexual aggression by female interrogators, loud music, strobe lights, and various bizarre schemes to humiliate him, such as having him wear a burka or signs on his head saying “liar,” “coward,” or “dog.”

The following July, daily torture began. Slahi recounts:

Suddenly a commando team consisting of three soldiers and a German shepherd broke into our interrogation room. Everything happened quicker than you could think about it. [Redacted name] punched me violently, which made me fall face down on the floor….

His partner kept punching me everywhere, mainly on my face and my ribs. He, too, was masked from head to toe; he punched me the whole time without saying a word, because he didn’t want to be recognized. The third man was not masked; he stayed at the door holding the dog’s collar, ready to release it on me.

Characteristically, at intervals in his narrative of his own torture, he pauses to reflect on the moral degradation of his assailants. “When I got to know [name redacted] more and heard him speaking I wondered, How could a man as smart as he was possibly accept such a degrading job, which surely is going to haunt him the rest of his life?”

At some point, after long abuse, Slahi began to tell his interrogators whatever they wanted to hear, in order to make the torture stop. He writes that he invented stories that he knew to be untrue because it was necessary and it seemed to be what his interrogators wanted. “I felt bad for everybody I hurt with my false testimonies,” he writes.

My only solaces were, one, that I didn’t hurt anybody as much as I did myself; two, that I had no choice; and three, I was confident that injustice will be defeated, it’s only a matter of time. Moreover, I would not blame anybody for lying about me when he gets tortured.

He may also have provided truthful testimony about al-Qaeda figures. The extent of his cooperation and the value of his truthful information is unclear from his memoir or from the available court records.

By the end of his narrative, Slahi’s generosity toward his keepers is also informed by a certain self-awareness about his subjugation, particularly the fact that, after violent and relentless coercion, he eventually cooperated and adapted to his confinement. Through prayer and Koran recitation he found nobility and even a form of defiance of his circumstances as he made these compromises. Yet he remained troubled:

At one point I hated myself and confused the hell out of myself. I started to ask myself questions about the humane emotions I was having toward my enemies. How could you cry for somebody who caused you so much pain and destroyed your life?…

I often compared myself with a slave. Slaves were taken forcibly from Africa, and so was I. Slaves were sold a couple of times on their way to their final destination, and so was I. Slaves suddenly were assigned to somebody they didn’t choose, and so was I. And when I looked at the history of slaves, I noticed that slaves sometimes ended up as an integral part of the master’s house.

Slahi’s status as a prisoner today is officially unchanged since his arrival at Guantánamo, except that he is in line for a review that could qualify him for release on the grounds that he poses no continuing threat. Even if he were judged culpable, his memoir and independent documentation of his torture, such as in the Senate report, would greatly complicate any attempt at prosecuting him. If Slahi does become eligible for release, he might be transferred to Mauritania.

It seems unlikely that he will retire quietly. “I don’t expect people who don’t know me to believe me, but I expect them, at least, to give me the benefit of the doubt,” he writes.

And if Americans are willing to stand for what they believe in, I also expect public opinion to compel the US government to open a torture and war crimes investigation. I am more than confident than I can prove every single thing I have written in this book if I am ever given the opportunity.

Unfortunately, Slahi has more faith in American democracy’s capacity for accountability than it deserves. A more realistic aspiration might be for the expiring Obama administration to find the courage and decency to send him home.

This Issue

January 14, 2016

ISIS in Gaza

How to Cover the One Percent

A Ghost Story

-

1

“Inquiry into the Treatment of Detainees in US Custody,” Report of the Committee on Armed Services, United States Senate, November 20, 2008, pp. 135ff. ↩

-

2

In Salahi [sic] v. Obama, 05-CV-0569, Slahi’s attorneys filed a writ of habeas corpus in federal district court in Washington. In March 2010, Judge James Robertson ruled in the prisoner’s favor. The Obama administration appealed and a circuit panel ordered the matter returned to the district court for additional review. The case is pending. ↩