The curtain rises in silence. The stage is empty except for four men with their backs to the audience evenly spaced across the rear of the stage. They are lean and long in their simple white T-shirts, black tights, and white ballet shoes, and they are doing nothing. Just standing. There is no set, no decor, no theatrical dressing of any kind—only space, light, and a blue cyclorama stretched behind them like the sky. Faceless, nameless, no smiles, no pretty balletic girls, no lush overture. Nothing but the four men’s backs and silence.

They swivel in unison to face us. And now it is not really silence anymore: this first move is on a musical rest, and although we don’t hear it the beat is there. Immediately the men catch it, take life, and begin to move. They bend their knees, walk, walk, counting paces, in diagonals, marking time, little catch steps, walking, walking, in twos and fours, until walking becomes dancing and they are off. From this moment until the ballet’s end some twenty-four minutes later, there is no respite: the pulse that began in silence is unrelenting and the four men are joined by eight women—black leotards, flesh tights and shoes, hair pulled tightly back, almost nude.

Agon is twelve bodies in propulsive motion in a suite of dances patterned on seventeenth-century dance and musical forms, refitted to the twentieth century with twelve-tone musical techniques. It is both tonal and atonal, often in uneasy juxtaposition. It is elegant, refined, gay; dissonant, broken, jarring. It is about math: there are four parts, twelve sections, and dances for two, three, four, eight, twelve dancers that accumulate with astonishing precision as dancers tear across the stage, bend, contort, toe shoes digging, pulling, striking their way through intricate footwork, legs flying, switchbacks, acrobatic extensions, gracious bows, physical and musical wit, and always on time (the pulse, the pulse).

Finally we are back to the opening music and the same four men, making their way upstage with sweeping arm gestures, as if they were painting the space all around. They stand facing us for an instant, recalling the opening movement, and then turn abruptly and freeze. The music stops. But there is a final rest—and in its silence, they swivel back to their original pose, backs to the audience.1 The pulse stops. They stop. It is over and the curtain falls.

The ballet had two opening nights: a preview performance to benefit the March of Dimes, followed by the premiere on December 1, 1957.2 George Balanchine was standing as usual in the front wing downstage right watching the ballet unfold, and the moment the curtain fell, as Edwin Denby memorably wrote, “the accumulated momentum of the piece leaps forward in one’s imagination, suddenly enormous…. People respond with vehement applause in a large emotion that includes the brilliant dancers and the goofiness of the fun.” In a thrall, the audience rose to a spontaneous ovation, with shouting, whistling, and curtain calls, until finally Balanchine walked from the wing to center stage and bowed humbly before slipping away again. Stravinsky was not there, but excited cables from friends and his son Soulima reported the success: “Have no words telling my enthusiasm…your music phenomenal Balanchine dances superb enormous success.” Marcel Duchamp said it felt like the opening night of The Rite of Spring in 1913, almost half a century before.

Agon, which Stravinsky neatly wrote in large Greek letters across the page of the manuscript and printed score, is the Greek word for “contest” and describes the intensely competitive spirit of Greek social and political life. Stravinsky and Balanchine, and many in the audience at the time, would have known of the idea of agon from Nietzsche who wrote admiringly of “agonist” culture and its concentration on perfecting the human body through discipline and physical training. This was not only a matter of personal vanity or gain: a competition was “won” for the city and seen as public good. The idea was not egalitarian—instead it was to cultivate an elite based on an aristocratic ideal of self. Stravinsky and Balanchine’s Agon was not an enactment of a competition in an antique setting. It didn’t have to be. Ballet was an Agon all by itself.

No wonder Balanchine liked to say that Agon was just dancers dancing. But they dance in certain ways, and not in others. To begin with, judging from contemporary sources including the 1960 television film featuring much of the original cast, the dancers move like the decor—plain, direct, exposed, calm faces, no acting. They look front, bodies front, eyes front—even positions in contrapposto or with a lilting épaulement do not seem lilting but appear direct and straightforward. The conventions of a proscenium stage as a real—or surreal—space had been jettisoned in favor of a poetic indication of infinity: light.

Advertisement

The original lighting by Nananne Porcher was built around ideas developed for the company by Jean Rosenthal of “light all around”: cold blue light pouring in from all directions—no follow spots, take out the gels, burn the brights—and not just from the footlights, but from the side wings too. The dancers’ nearly nude bodies appeared translucent, nothing hidden. The idea—far more radical than any set design—was of a stage without shadows or dim corners so that every curve, line, bone, ligament of the body would be X-ray visible. It was a paradoxical combination of unreal and hyperreal, a kind of ghostly or angelic muscularity. The dancers’ simple leotards and tights similarly recalled at once an idealized classical human figure and a concrete contemporary reference: work clothes, a uniform—black and white, impersonal and anonymous.

The movement vocabulary of Agon is simple, almost pedestrian at times: walking, small steps, the leg—turn in and turn out—showing the human body from every angle, and building to a complicated series of intricate movements that are rarely strictly classical in form. The dances are more about the mechanics of the body than about balletic steps, beauty, or line. There is visible effort and the dancers in early films of the ballet can often barely do what’s asked of them, which means we are with them in the raw moment of physical exertion, calculating and improvising as they find a way into and out of a step, which is itself a kind of intimacy. They are in nearly every possible way exposed.

Who are these twelve dancers? Like the twelve tones in the music, they are an ensemble of equals and the traditional hierarchies of ballet no longer exist. Soon after the ballet begins, there is a kind of tableau: they are all there, posed as in a family photo. This is our group and their dances break out from here and pile up, like episodes stacked one on top of another. The man and woman who will perform the pas de deux are not stars but part of the ensemble and the clock-ticking order of the ballet. Moreover, the three interludes, as Stravinsky noted, “are in the same music but in variation,” which keeps us oriented but also pulls us into a ritual repetition, like an event compulsively replayed with new people; a bow or gesture and a dance is over and gone, but in fact we are not done with it yet.

Agon is a woman’s world. The four men open and close the event and have the first and last breath, but the eight women dominate: they are confident, even aggressive, and with the notable exception of the pas de deux, barely in need of male support. Their music is often rivetingly chromatic and they are the source of the ballet’s primal energy and self-assurance, and of its humble grace. They are en pointe, but their toe shoes are not used to emphasize the ethereal and are instead made to dart into the floor, propel the body, mark time, extend the leg not up but down into the ground, weight low, or precariously suspended. They are instruments of mathematical precision, of logic and calculation, not of emotion or feeling.

The shoes, like the costumes and light, add to the abstract, intellectual atmosphere of the ballet, like an “IBM ballet…controlled by an electronic brain,” as Balanchine himself put it. Even when the woman in the pas de deux, for example, finds herself on one leg in arabesque en pointe, she is not gracefully posed, but fighting to stay up, gripping her partner’s hand, arm quivering with the effort as he flips onto his back on the floor, barely within her reach. The dime-sized tip of her pointe shoe, which is the only part of her body touching the ground, is not raising her to the heavens but daring her to balance here on earth.

Events unfold. There is no “story” or traditional narrative flow. Instead everything feels compressed and discrete, brick on brick, mass on mass, like a kind of ballet montage. The only story is the pulse—time—that pushes irretrievably on and keeps the dancers—and us—in its grip. We hang on every beat, and the experience is intense, engrossing but also joyful and fun, because it is fun to be on time and in time—to divide, count, multiply, keep up. When on opening night in 1957 Melissa Hayden, a dancer with wonderfully sharp technique, coolly mastered two competing rhythms simultaneously in a complicated dance that resolved with split-second timing on the last note, the audience, Denby reported, “caught the acute edge of risk” and broke into a spontaneous “roar” of applause. The bravura was never the show-off kind, and in a nod to the seventeenth century, the dancers are impeccably behaved: they bow and gesture gracefully even as they speed through the intricate traffic patterns and involved physicality of the dances.

Advertisement

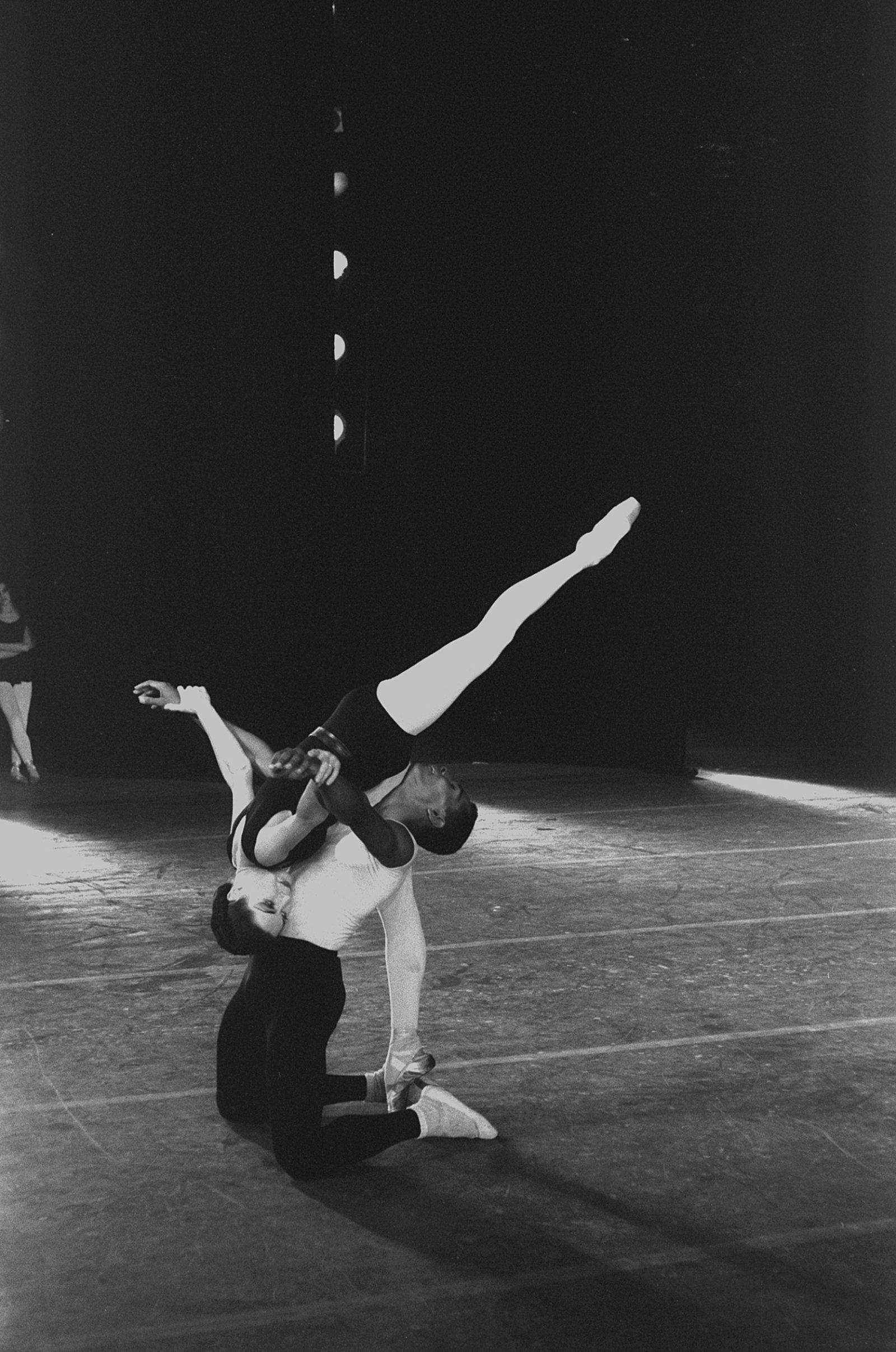

Nowhere in Agon is Balanchine’s strange and unhinged classicism more fully explored than in the pas de deux, which clocks in at six minutes, by far the longest and most sustained dance in the work. When he made Agon, Balanchine started with this dance for Diana Adams and Arthur Mitchell and everything flows into and out of its entangled forms. The couple enter in silence and stand at the back corner of the stage. The music begins and they race out across the space on a diagonal, her first, him behind, sweeping legs, double turn (her), double turn (him) in hot pursuit until she dives forward and whips her leg backward, catching him around his head and they stop. In this striking and unstable position, time seems for a moment to suspend.

They gather themselves with small classical steps and a return to etiquette, holding hands, in unison. Then they face each other close—too close—body to body, face to face, but they quickly flip back to back, and she leans, spider-like, almost crawling on his spine. And so they begin and continue: back to back, never really looking at each other, limbs interlacing with effort—leaning, pressing, sustaining their mutual dependence in uneasy and precariously counterbalanced partnering. There is no woman on a pedestal, no romance or courtship here; this dance is between them, and we are watching, spying almost. It is never quite clear who is in control, and there is always the fact of sex in the movements, which are nonetheless performed in the ballet’s perfectly blank, matter-of-fact way—his hand through her crotch, his head diving between her legs, her legs split wide; it is not sexy but sex is there.

Balanchine told Adams and Mitchell, “The girl is like a doll, you’re manipulating her, you must lead her. It’s one long, long, long, long breath,” and Mitchell has said that the key to the dance is for the woman to let the man move her, puppet-like. Indeed in the films Adams appears to move and contort her body almost without will. She watches him as he takes her foot, guides her leg, holds her ankle, and she twists, turns, supports herself on his body as if it were all happening to her. He doesn’t embrace her, he embraces her leg, or her arabesque; she doesn’t embrace him, but stands en pointe on one leg and places her leg dangerously on his shoulder and waits. By the end he is on his knee to her, gazing up—a courtly pose—but instead of taking her hand, their arms circle, each in their own orbit, without finding their way together—much less to any possible kiss. On the last beat her arm falls heavily on his head as they both slump, her over him. Defeated.

As a dancer and as a person, Adams was naturally cool and remote, with something anxious and troubled inside. Mitchell was her opposite: he had “fire” in his movements, as Melissa Hayden once put it, and it was the contrast between them that seemed to interest Balanchine. He tried for years to bring Adams out of herself, encouraging her to do more, let go, really dance, but she wouldn’t, or couldn’t, and her dancing always had a deep formality and self-restraint. In Agon he found a way: he made a dance about her remoteness and in the end it is Adams who moves us, not in the usual ways by acting or conveying emotion but instead by withholding.

The dance was complicated further still by the fact that Mitchell was an African-American from Harlem and Adams was a pale white beauty from Virginia. The ballet premiered at a particularly tense moment in the civil rights movement, and the simple fact of a black man and a white woman performing publicly half-naked and physically entwined—black purposefully on white, however aestheticized—added to the electric charge in the theater that night.

The dancers were on edge for other reasons. They had become accustomed to hearing the music on the rehearsal piano, played by Balanchine’s friend and colleague the Russian émigré musician Nicholas Kopeikine. Even that had been a struggle: faced with the score in a rehearsal with Stravinsky and the dancers, Kopeikine nervously admitted, “I’m terribly sorry. There are parts of this music I don’t understand,” to which Stravinsky responded, “It’s perfectly all right. I don’t understand them either!” Balanchine counted the music, snapping his fingers, hitting his leg, or bent over the score, and the dancers followed, but some also made up their own counts (Balanchine later cautioned: a five and seven are not the same as a twelve), which meant that when they got on stage there were several competing versions, each dancer hissing counts under her breath as they all strove to keep up and stay together.

Things were made harder still by the fact that when the curtain rose on that opening night, the dancers had barely heard the music with a full orchestra (there was no recording yet). Everything sounded different than it had in the piano rehearsals, and one dancer recalled her panic: “Oh my God, where are my counts?” The dancers say they had to concentrate and listen very, very hard. Meanwhile, the musicians were concentrating and listening hard too: Leon Barzin, who conducted, was not a Stravinsky expert and the musicians had had their own troubles with the irregular tempos and complicated demands of the new score. Add to this the blindingly bright lights hitting the dancers at eye-level from the wings and it is no wonder many recall feeling unnervingly exposed and alone on the empty stage with no plot, no costumes, only counts—and the fun and pulse of the dancing itself—to hold on to. One dancer later said it was like being on the high peak of a mountain or balancing on a platform suspended in light. You could fall off.

Agon has been many things since 1957. New casts, new theater, a changed and expanded company; improved and more subtle and sophisticated dance technique; powerful new technology and lighting design; different bodies that move in different ways. New politics. New civil rights. New fashions. And no one today has to listen very hard to Stravinsky: now we can “whistle [his music] on the street” as Balanchine himself pointed out back in the 1960s. Think of the difference in the pas de deux woman alone, between the cool demure Diana Adams and the impulsive, agonistic Heather Watts, the last dancer to perform the role under Balanchine, who died in 1983. When Adams saw Watts do “her” part, she offered a word of advice: “don’t be so animalistic.” But Watts was animalistic and she was utterly fascinating to watch. Hers was a different Agon. Then there’s been the technically smooth and detached—and very white and blond—Dane Peter Martins, who (among others) danced Arthur Mitchell’s part. Balanchine changed his own ballet not by changing the steps but by changing the people and adjusting to new times, personalities, circumstances.

Over all of those years, from Adams to Watts, however, one thing stayed the same: Balanchine. He chose. He coached—Agon was a ballet he did not often delegate—he worked with the musicians, the lighting designers, he “assembled” (as he liked to say) the ballet in all of its many parts. It was his ballet because it was his company. He was very clear that Agon should be danced only by “particular people. I don’t think that everybody should do that. Later, people do, but I don’t care about it, you see.”3 He didn’t care because he wasn’t (wouldn’t be) there and it wasn’t his to care for.

So perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised to find that Agon performed by Peter Martins’s New York City Ballet at the Koch Theater today is a very different ballet. It doesn’t look or feel anything close to the way it did in 1957, or even in 1982. And why should it? In many ways, Agon has become its opposite: the dancers are fully in control of themselves and their steps and any sense of living at “the acute edge of risk” is gone. The movements that seemed so new and spontaneous, even in the last years of Balanchine’s life, now appear fixed and choreographed and the dancers perform them with consummate skill and ease: Agon has achieved the dubious status of a “classic.” If today’s Agon is a willful and beautifully groomed creature, a dance as smooth as glass performed by serious and accomplished dancers, it would be wrong to assign blame. Indeed, blame would imply that there is a ballet there that they are in some way not getting right. But Agon was never really a ballet. It was always more of a man: George Balanchine.

-

1

In the 1960 film of the ballet, and probably in its opening-night production in 1957, the dancers froze at the end of the ballet without returning to their original pose, but the return to the facing back pose was part of the original plan indicated in Stravinsky’s published and manuscript scores, and soon became common practice: “The male dancers take their position as at the beginning—backs to the audience.” ↩

-

2

The preview took place on November 27, 1957. ↩

-

3

Interviews with George Balanchine and members of the New York City Ballet. Interviewer: Jac Venza. Recorded in 1964 (?) for the National Educational Television network program The American Arts. ↩