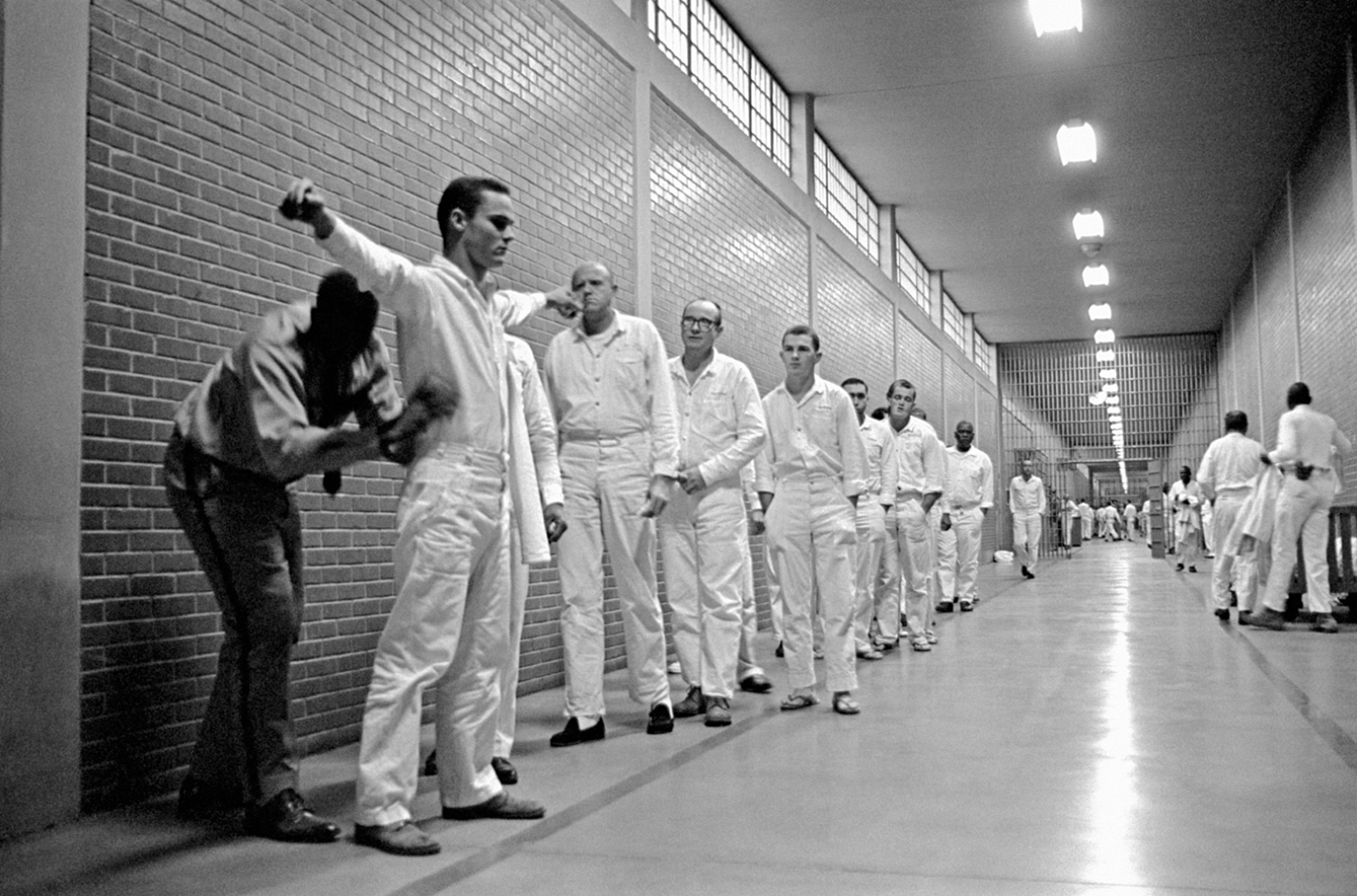

Magnum Photos

A shakedown of inmates in the main corridor of the Ellis Prison Farm, Huntsville, Texas, 1968; photograph by Danny Lyon from his 1971 book Conversations with the Dead, which has just been reissued by Phaidon. A retrospective of his work, ‘Danny Lyon: Message to the Future,’ will be on view at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York City, June 17–September 25, 2016.

Some time ago, I was at a book festival in Finland. When there was a free day, the publisher who had invited me asked if there were any sights I would care to see. I said I’d like to visit some prisons. Finland locks people up at well under 10 percent the rate we do in the United States, a gap far more dramatic than all the differences between the two countries’ populations could explain. I was curious to see what prisons in this society looked like.

Kerava Prison, the first of the two that I saw, was in the countryside half an hour’s drive north of Helsinki. Its governor—by design, the title has a civilian sound—was a warm, vivacious, gray-haired woman named Kirsti Nieminen, a former prosecutor. On this wintry morning, she had about 150 prisoners in her charge, all men. Her office wall was lined with portraits of former governors, the first a heavily bearded one from the 1890s. Next to these was a framed drawing from a prisoner—Snoopy typing a letter, which she translated for me: “Dear Governor, please give me a leave!”

The rough equivalent of an American medium-security prison, Kerava had barbed-wire fences, bars on some windows, and plenty of locked doors. Some convicts worked in greenhouses outside the walls, but only if they were trusties or under guard. Most resemblance to American prisons ended there. In the greenhouses the inmates raised flowers, which were sold to the public, as were the organic vegetables they grew. As we walked, Nieminen pointed out a stream where prisoners could fish, a soccer field, a basketball court, a grain mill, and something she was particularly proud of, a barn full of rabbits and lambs. “The responsibility to take care of a creature—it’s very therapeutic,” she said. “They are always kind to you. It’s easier to talk to them.”

For an hour or so, I had coffee with half a dozen prisoners. Marko, thirty-six, wore a visor and had tattoos and said he was here for a “violent crime” that he did not specify. Jarkko, a burly twenty-six-year-old, was doing three years and ten months for a drug offense; Reima, thirty-six, blond and tough-looking, was in for robbery. Kalla, at forty-eight the eldest, had committed fraud; Fernando (his father was from Spain) was twenty-six, convicted of armed robbery and selling heroin; Harre, twenty-seven, was doing five years for selling Ecstasy. Also sitting with us, and helping with translation, were Nieminen, a young woman from the national prisons service, and two of Kerava’s teachers, also both women. No armed guards were in sight, and both officials and convicts wore their own clothes, not uniforms.

This was still a prison, however, and at 7:30 each evening the inmates were locked in their two-man cells. These were not large but somewhat more spacious than those I’ve seen in American prisons, each with a toilet and sink in a cubicle whose door closed. Prisoners were allowed TVs, stereos, and radios. Down the corridor were a shower room and sauna—something no Finn could imagine being without.

Prisoners were assigned jobs, but most spent much of their day in classes on subjects including auto repair, computers, welding, cooking, and first aid. A library held several thousand books—more than you would find in many American high schools—and inmates could use the national interlibrary loan system to get more. I attended a cooking class and shared a tasty lunch its students had prepared: Karelian stew, which included beef, pork, potatoes, and cranberries.

All this was obviously another world from the overcrowded and underfunded prisons of the United States, where classes, if they happen at all, are often a slipshod afterthought. When the former Missouri state senator Jeff Smith was sentenced to a year and a day in a federal prison in Kentucky, he hoped that as a Ph.D. who had taught at Washington University in St. Louis, he would be put to work teaching. Instead, as he writes in his book Mr. Smith Goes to Prison, he was assigned to the prison warehouse loading dock, where he observed and took part in the pilfering of food by both inmates and guards. A month from the end of his stay he was finally transferred to the education unit—and told to sweep out classrooms. A computer skills class consisted of the chance to sit at a computer for thirty minutes, with no instruction whatever; at a nutrition class, a guard “handed out a brochure with information about the caloric content of food at McDonald’s, Bojangles, and Wendy’s and released us after five minutes.”

Advertisement

Particularly at the college level, an effective prison education program, like the well-known one run by Bard College, can cut the recidivism rate—in the US 67.8 percent after three years—down to the single digits.1 The Bard program, for example, offers classes leading to a college degree. They are taught by professors from Bard and other campuses and attended by nearly three hundred inmates in six New York State prisons. A debating team drawn from these students won national attention last year when it beat a team from Harvard. Reducing recidivism through such efforts not only is humane but also saves money, since keeping someone locked up is hugely expensive; it costs New York State more each year to house and guard a single prisoner than the total tuition, room, and board for a Harvard undergraduate. You would think that budget-conscious legislators would act accordingly, but reason has never played much of a part in American prison policy.

In his book, Smith spends far too much time telling us about the campaign spending law violation that put him behind bars. Some of what he writes recalls many other American prison memoirs: he describes de facto racial segregation, rapes, etiquette (never sit on someone else’s bunk), and the underground economy. Prices for pornography, cell phones, and other contraband rose sharply when snow on the ground made footprints visible or when a notoriously vigilant guard was on duty. And contrary to the film The Shawshank Redemption, in which the character played by Morgan Freeman wryly observes, “Everyone in here is innocent,” Smith says that few prisoners make that claim. Instead they blame their fate on the “snitch” who turned them in.

For me the most moving part of the book is its picture of what prison does to families. Smith points to research showing that “half of all incarcerated fathers lived with their children, a quarter served as primary caregivers, and over half provided primary financial support.” When a man goes to jail, his family shatters:

While I was waiting to use a phone, it was hard to avoid hearing their anguished phone conversations with ex-girlfriends who controlled access to their children, with rebellious teenagers who—lacking a male authority figure at home—were in some cases following in their fathers’ footsteps, and with dying parents far away.

One of Smith’s workmates, known as Big E, had been an ace basketball player and was serving seventeen years for possession of crack cocaine. One Saturday in the television room there was none of the usual haggling about which sports game would be watched. Big E’s son, a college freshman, was playing, “and Big E, the best shooter on the compound, had never seen his son play.” He had been in prison since the age of nineteen.

How did we get to the point where a nineteen-year-old who has done nothing violent can be put away for almost as long as he has lived, where prisons break up millions of families, and where we have a larger proportion of our people incarcerated than any other country in the world, even Putin’s Russia? We have so many prisoners that the American unemployment rate for men would be 2 percent higher (and 8 percent higher for black men) if they were all suddenly let out. Our jails are so packed that through the website www.jailbedspace.com wardens and sheriffs can look for space in other facilities if their own is full. Arizona and California have even considered plans to house inmates in Mexico, where costs are lower.

New books on the subject of prison range from James Kilgore’s clear, lively, and well-illustrated handbook to highly academic works by Naomi Murakawa and Elizabeth Hinton, who are both intent on showing how much liberals helped lay the foundation for the mess we’re in. The best of the recent studies is Marie Gottschalk’s carefully documented book Caught. It is hard to imagine a more comprehensive analysis of our shameful crisis.

The two most conspicuous parts of the story are, first, the unwinnable war on drugs, and second, the Republican tough-on-crime politicking that reached its climax with the notorious Willie Horton advertisement in George H.W. Bush’s successful 1988 presidential campaign. (The ad attacked Michael Dukakis for having supported the weekend furlough program that gave Horton, a convicted murderer, the chance to commit additional violent crimes.) But Democrats helped build the prison system as well. Starting in the 1940s, looking for ways to stop the lynching of blacks and their abuse by police in the South and fearing a recurrence of the World War II–era race riots in the North, liberals pushed for more professional training for law enforcement officers.

Advertisement

The southern Democrats who then controlled Congress transformed these efforts into giving block grants to states. As a result, police departments received more money and more advanced hardware with which to do business as usual. Liberals also pushed for standardized sentences that would curb the discretionary powers of racist judges. But the mandatory minimums have now become cruelly high, and the definition of crimes, with no mention of race, ended up with vastly greater penalties for possession of crack cocaine (used mostly by blacks) than for possession of powdered cocaine (used mostly by whites).

The 1960s brought immense social turbulence and a sharp rise in almost all types of crime. Quick to moralize against disorder and drawing on the deep American reservoir of racism and paranoia that previously drove lynch mobs, politicians promised a ruthless response. New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller sponsored drug laws that put several generations of men, largely black, away for decades. Authorities across the country acted so harshly in part because the United States chooses a sizable proportion of its judges and almost all of its district attorneys and county sheriffs by popular election—something that would be considered bizarre almost everywhere else in the world. (One recent study of Washington State judges found that the sentences they passed out lengthened by an average of 10 percent as reelection day approached.)

By the time Bill Clinton entered the White House in 1993, he and congressional Democrats were determined to show that they were tougher on crime than Republicans. The following year Congress passed the brutally severe Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act and the Federal Death Penalty Act, which, among other things, added some sixty offenses to the list of capital crimes.

The prison boom has also been a chance to make money. One private prison company alone, the Corrections Corporation of America, today runs the country’s fifth-largest prison system, after those of the federal government and the three biggest states. The less money such corporations spend on staff training, food, education, medical care, and rehabilitation, the more profits they make. States, at least in theory, have a financial incentive to reduce recidivism, but for private prisons, recidivism produces what every business wants: returning customers. No wonder these companies push hard for three-strikes laws and similar measures. In 2011, the two biggest private prison firms donated nearly $3 million to political candidates and hired 242 lobbyists around the country. Another industry with a vested interest in keeping prisons full, writes Jeff Smith, is that of food wholesalers, who know that this market of 2.2 million people is powerless to protest if much of the food delivered to them is well past its sell-by date.

The prison-industrial complex is now as deeply rooted as its military counterpart. With both corporate profits and government salaries at stake, it will be equally difficult to shrink or transform. There is much talk just now of how politicians on both the left and right agree that our prisons are too full. More than twenty public figures, ranging from Ted Cruz and Scott Walker to Hillary Clinton and Joseph Biden (an architect of the wider application of the death penalty in the 1990s), have contributed to Solutions, a new anthology calling for reducing mass incarceration.2 Marie Gottschalk, however, shows why none of the proposed solutions—such as Cory Booker’s recommendation to assign judges “more discretion in sentencing” or Cruz’s call to reduce mandatory minimum sentences for nonviolent drug offenders—either singly or together, is going to reduce the proportion of Americans in prison to anywhere near what it was fifty years ago.

Gottschalk agrees that our drug laws are absurdly punitive. But “if all drug cases were eliminated, the US imprisonment rate would still have quadrupled over the past thirty-five years.” And it is true, she agrees, that there are appalling disparities in how different races are treated before the law. Hispanics are more than twice as likely to be in prison as whites, and blacks more than five times as likely. But she shows that even the rate at which white Americans are locked up is more than four times that of all prisoners in multiethnic France. Clearly the penalties for many nonviolent offenses should be more lenient. But that alone, she points out, is not sufficient, for nearly half of those behind bars in America are there for violent crimes.

Too few officeholders, she says, are willing to take two necessary steps, each of which means reversing decades of political rhetoric. One is to acknowledge that for a wide variety of crimes, prison sentences accomplish nothing. Communities ranging from Brooklyn to Oakland, California, have made encouraging experiments in “restorative justice,” in which convicted criminals are sentenced to apologize to those they hurt, repay people they robbed, and take part in improving the communities they have harmed.3 But promoting such programs is not a promising path to election for most district attorneys.

The other urgent task, in Gottschalk’s view, is to ensure that when we do have to send people to prison, they have much shorter sentences. It used to be that a life sentence meant that a well-behaved American prisoner was likely to be released after ten to fifteen years—a recognition that aging has far more influence than length of time served on the likelihood that someone might commit another crime. But mandatory minimums and other disastrous results of tough-on-crime campaigns mean that US prisons are filled with people serving several consecutive life sentences, or life without parole—a punishment that virtually did not exist half a century ago and is almost unknown in the rest of the world.

“The total life-sentenced population in the United States is approximately 160,000,” Gottschalk writes, “or roughly twice the size of the entire incarcerated population in Japan.” And some alleged reforms are meaningless: “The governor of Iowa commuted all the mandatory life sentences of his state’s juvenile offenders but declared that they would be eligible for parole only after serving sixty years.” This reminds me of a similar act of clemency by King George IV of Britain in 1820, when five members of the revolutionary Cato Street Conspiracy were sentenced to be hanged, drawn, and quartered. The king remitted the last two parts of the sentence to mere beheading.

Breaking the pattern that has so many men, women, and teenagers wasting their lives in custody also demands bettering their opportunities for education, jobs, and much more on the outside. It is telling that the Nordic countries, with some of the world’s lowest imprisonment rates, are highly developed welfare states and far more egalitarian than the United States. Programs that promise inmates “a second chance” on release, Gottschalk writes, mean little when “many of the people cycling in and out of prison and jail were never really given a first chance.”

This is all too true. But much as I would like to see Nordic social democracy replace our own wildly unequal distribution of wealth and opportunity, that day will not come soon, if ever. We cannot wait until then to drastically reduce the number of people we have in prison. Even counting white prisoners alone, the United States has well over twice as many people, per capita, locked up as Spain, where 20 percent of the population is out of work and the welfare state is weaker than in Scandinavia. And we have more people per capita of any single race in prison than South Africa, where the unemployment rate for the black majority is catastrophic and the welfare state barely exists.

Was there ever a country that was enthusiastic about imprisoning people but changed its ways dramatically? Finland did so. In 1950, with a prison system and criminal code that had changed little from their origins under the Russia of the tsars, Finland had a higher incarceration rate than we then had in the US. One hundred eighty-seven people out of every 100,000 were behind bars, while we had only 175. A long series of reforms—not without their hard-line opponents—brought the Finnish rate of incarceration far down just as our own soared. Today we have 710 people per 100,000 in prison in the US, compared to fifty-eight in Finland.4 “One important idea that emerged,” write two scholars of Finland’s changes, “was that prison cures nobody. As a result policies were enacted that prison sentences should rarely be used in smaller crimes and other penalty systems should be developed instead.”5

Although the prisons I saw in Finland certainly isolated inmates from the outside world, much that happened inside them seemed directed toward making sure that released prisoners could return to society. With special permission, someone with half his sentence completed could leave Kerava Prison on weekends. Everything possible was done to ease that transition. The diploma you get on completing one of the classes, for instance, is certified by an outside organization; it doesn’t say you received your training in prison.

A host of services within the prison addressed the problems that landed men in trouble in the first place. There were programs for anger management and drug rehabilitation, as well as both individual and group psychotherapy. Prisoners could also take part in a twelve-step program similar to Alcoholics Anonymous, and a three-times-a-week class in life skills. And there was a series of speakers, copied from Sweden: former convicts who shared their experiences of readjusting to the world.

A released prisoner in the United States is frequently barred from voting, public housing, pensions, and disability benefits, and is lucky if he receives anything more than bus fare and, according to Jeff Smith, a routine farewell from a guard: “You’ll be back, shitbird.” In Finland, before a prisoner is released, a social worker travels to his hometown and makes sure that he will have a job and a safe place to live. Small wonder that Finland’s recidivism rate is far lower than our own.

-

1

The rate can be calculated in different ways, but in a recent Department of Justice study, this was the proportion of some 400,000 prisoners from thirty states who were arrested for a new crime within three years of being released from prison. The full report can be found at www.bjs.gov/content/pub/pdf/mschpprts05.pdf. ↩

-

2

Solutions: American Leaders Speak Out on Criminal Justice, edited by Inimai Chettiar and Michael Waldman (Brennan Center for Justice, 2015). ↩

-

3

For more on restorative justice, see Helen Epstein, “America’s Prisons: Is There Hope?,” The New York Review, June 11, 2009. ↩

-

4

Melissa S. Kearney and Benjamin H. Harris, “Ten Economic Facts About Crime and Incarceration in the United States,” Brookings, May 1, 2014. Other calculations give slightly different figures. ↩

-

5

See Ikponwosa O. Ekunwe and Richard S. Jones, “Finnish Criminal Policy: From Hard time to Gentle Justice,” The Journal of Prisoners on Prisons, Vol. 21, Nos. 1 and 2 (June 2012), p. 178. ↩