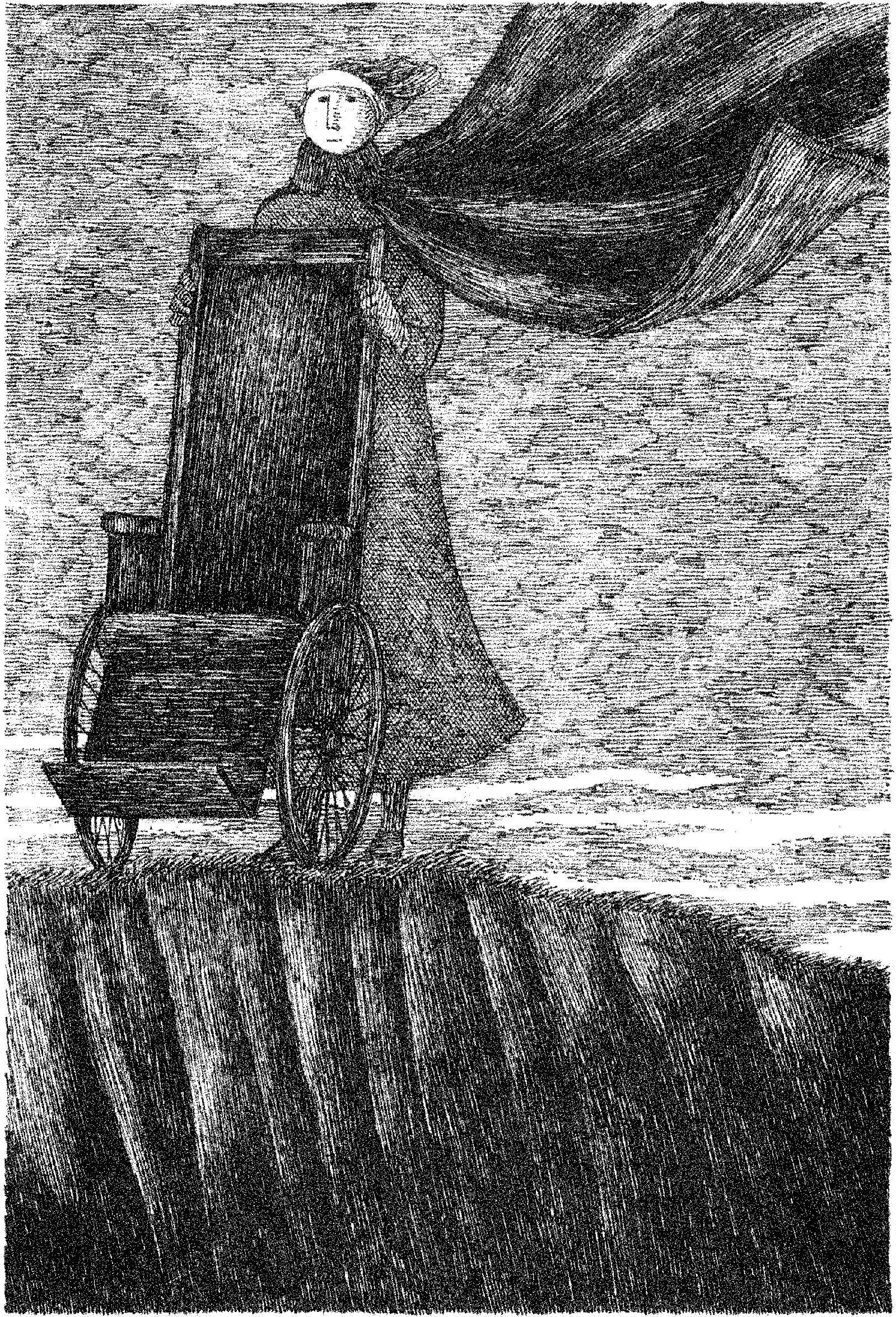

Over the past thirty-three years, Cathleen Schine has been one of our most realistically imaginative, dependably readable novelists. Starting with Alice in Bed (1983), her ten books comprise a sly, illuminating corpus that seems more related to the English comic novel than to most contemporary American fiction. Her work is as shapely and precisely structured if more generously cluttered than Barbara Pym’s, one of her avowed models; as ruefully satiric though less tart than Muriel Spark’s, another acknowledged influence; as buoyant though less panoramic than Anthony Trollope’s (a favorite); as sharply observant though gentler and not as grim as Anita Brookner’s.

Schine often writes about educated New Yorkers—editors, academics, booksellers, curators, downwardly mobile members of the bourgeoisie, usually Jewish, whose families may have had some money but who are now just scraping by, thanks in part to their obstinate bookishness. An ethical tribe, they are blindsided by their lusts, baffled by ambivalence toward their mates and parents, and unsure whether to carry on stoically or make a run for liberation. Culturally sophisticated if not always self-aware, they trade wisecracks and witty, self-deprecating dialogue that deflect and defend their vulnerability. Two of her novels, Rameau’s Niece (1993) and The Love Letter (1995), have been made into movies; and those of her books that fall short of their initial promise leave you at times with the pat sensation of watching a Nora Ephron romantic comedy.

Her tenth and newest novel, however, cuts deeper, feels fuller and more ambitious, and seems to me her best. The book’s odd-sounding title, They May Not Mean To, But They Do, derives from the infamous Philip Larkin poem “This Be The Verse”:

They fuck you up, your mum and dad.

They may not mean to, but they do.

In Schine’s reversal of the formula, it is the well-meaning children who screw up their elderly parents’ lot. The Bergman family is introduced to us at the start of the novel: “They were like a cult,…tight knit and suspicious of strangers. They were tribal and closed, bound by blood. They were one, the world the other.” Moreover, “the Bergmans were New Yorkers, [who] had always been New Yorkers.”

Joy, the matriarch, is in her mid-eighties and has been married all her adult life to Aaron, an irresponsible charmer who had wanted to be a classical singer but instead went into the family’s well-run business, which he managed to bankrupt. They have two middle-aged children, Molly, an archaeologist, and Daniel, an environmental lawyer. Molly has broken the family mold, first by divorcing her husband to marry a woman, Freddie, and second by moving to California.

Molly has found happiness with Freddie in sunny Los Angeles, but she feels guilty for abandoning her parents, especially at a time when her father has been sinking into dementia, with the full burden of taking care of him falling on her mother. Compensating for her guilt, Molly keeps flying back east for brief visits, during which she tries officiously if unavailingly to put her parents’ lives into order:

As soon as she got to New York she would call her parents’ various doctors. She would organize all their medications in little plastic boxes labeled with the days of the week. She would order a lamp with a high-wattage bulb for reading, a telephone with big buttons and an extra-loud ring. She would put all their bank accounts online and arrange for deposits and payments to be made automatically. She would set up Spotify and program it to endlessly play Frank Sinatra.

She said these things to herself to make herself feel better, but she knew what would really happen. Neither her father nor her mother would be able to decide which doctor she should speak to or find their phone numbers. The medications she organized would be the ones they no longer took…. She had tried once to arrange a regular delivery of decent produce through an organic food website. It had not been a success. Her mother did not like the dirt on the vegetables. Her father did not like the irregular shapes. Neither of them liked rutabagas.

Molly’s and her brother Daniel’s eagerness to act responsibly, to do the right thing by their parents, keeps running up against the unruly realities of sickness and dying. Unlike the occasionally nasty characters in Schine’s previous books, everyone here is nice, or determined to be so (“Molly did not like to think of herself as selfish”); and their very sense of obligation ruins the effect. Daniel, exhausted from his barely remunerative climate control advocacy, starts coming by once a week for dinner with his mother:

He did it to be nice, she knew. Which both touched and saddened her. We all prefer to have someone visit for our company rather than be kept company, but she must not be greedy, she reminded herself.

Aaron is the sole exception to the niceness rule, but he has the excuse of being demented, and keeps screaming insults at his long-suffering wife, when not delivering himself of bland, all-purpose responses such as “Imagine that” or “Who knows.” When he dies, midway through the book, Joy is left bereft, grief-stricken, empty.

Advertisement

The focus of the novel then shifts from Molly, who had seemed at first its central intelligence and author-surrogate, to her mother, Joy. The novel’s triumph lies in Schine’s empathetic ability to inhabit this courageous, intelligent, wounded old woman. Joy had gotten a Ph.D. later in life and had gone to work as a “conservation consultant for a small museum on the Lower East Side that specialized in Jewish artifacts.” Though still at work when the book begins, juggling the job with taking care of her husband, she is eventually forced out. Widowed and unemployed, she no longer knows what her function is, or where she belongs.

In some of the most strikingly written pages, we enter into Joy’s thoughts, examining her bleak options with a clear eye. While her children are congratulating themselves, “thinking of their mother safe, clean, and comfortable in her apartment, her Life Alert wristband securely fastened,” she awakes each morning with the heartbreaking realization that Aaron is dead:

Joy began to feel that there was another person in the apartment, a stranger, and it was her. She had to watch over this person, this boring, fearful, sickly person. She had to make sure it took its pills. She had to watch its step so it didn’t fall. She made sure it chewed its food so it didn’t choke. She worried about the person constantly; the worry was a weight heavy on her shoulders, on her mind, on her heart. It followed her as she followed this person from room to room, this awful, needy person who was herself.

She thinks maybe she should complain, but it goes against her stoical nature, and in any case, when she did complain to the children, “the response had not been entirely satisfactory.” So she takes to joking about her situation on the phone, raising a relieved laugh from Molly. “That was another of the responsibilities Joy had, relieving her children of worry.”

Joy is also acutely aware that if she were to fall, break a hip, or show incapacity in any way, they might think of putting her in assisted living:

They watched her like hawks to make sure she was okay, and like a field mouse she scuttled and hid. Yes, I’m doing quite well, she would say. Nothing to report.

Schine nails one of the terrors of old age, this need to camouflage one’s frailty, lest one be shipped to a nursing home. As well, there is the negative narcissism of watching the physical equipment worsen. “She examined her face in the mirror and took a certain satisfaction in its fall from beauty. It was the only power she seemed to have anymore—the power to deteriorate.” Nevertheless, an old (in both senses) ex-boyfriend, Karl, arrives on the scene and begins to court her. He still finds her beautiful. Though not in any hurry to take him up on his proposal, she is flattered. “There was also the physical frisson, it was still there, the few ancient remaining hormones rearing their heads like old warhorses at the sound of a trumpet.”

Her children are deeply offended, however, when Joy invites Karl to a family seder. Aaron, they cry, has not even been dead for a year. They are determined to “protect” her from this wealthy new-old beau, though why they think she is endangered is anyone’s guess. Joy tells one of her girlfriends: “First they want me to stop grieving. Then they think I’m not grieving enough.” She marvels at “her two beloved children, yelling and stamping their feet like toddlers. Graying toddlers.”

Not that Joy is so easy to accommodate. Like the Jewish mother in standard jokes, she is adept at turning the tables. Reassured by her daughter, “I miss you, too, you know,” she quickly retorts, “I should hope so.” When they discuss whether to sell their country house in order to provide Joy with some much-needed funds:

“Oh, Mommy,” Molly said, her voice tearful. She took her mother’s hand and squeezed it. “You know you don’t have to leave Daniel and me anything.”

“So you do want me to die with nothing.”

Molly is expected to help her mother more, because, as Joy’s friends sagely counsel, wonderful as her son might be, “Daniel was not a daughter.” That very expectation leads to competition and conflict between mother and daughter: when Molly moves to take over the Thanksgiving preparations, Joy says to her, “I don’t want to give up my place as the matriarch,” even as she retreats from the kitchen.

Advertisement

Molly wrestles with guilt over her “geographical treachery,” needing to speak on the phone with her mother every day. “I love her voice. I love to hear it. Until I can’t stand it anymore!” she tells her impeccably understanding wife. (Freddie, a tenured English professor, warm, compassionate, and gracious, remains the one character who seems idealized, not quite real. Nor does a subplot involving her family ever take root.) In a similar vein, Molly wonders, “Why don’t we revere the elderly?” Before she can get too far in this sentimental speculation, she cuts it short. “She knew why. They were difficult and inconvenient.”

Joy, meanwhile, realizes that her children’s offers to have her move in with them are merely pro forma. “They were good, devoted children, just as she had been. They didn’t really mean it….” As it is, Molly and Freddie invite her to spend some time with them in California, and the visit does not go well. Despite—or because of—the fact that everyone is trying so hard, Joy feels like an intruder. “I have no life, Joy thought. I belong nowhere. I am residing in someone else’s life, in the Two Girls’ life.” The girls get her a dog for company, and an adult tricycle to tool around the neighborhood, and recommend that she become a volunteer docent at the Getty Museum. All she wants is to get back to her sad apartment in Manhattan, where she can be alone. Joy tells Karl:

Molly and Daniel want me to be happy, but they’re driving me crazy. I think someone of my age and experience should be allowed to feel exactly the way she wants…. Which is miserable.

Schine shows a finely nuanced understanding of the ways that parents and children can love each other without question, yet get on each other’s nerves. Joy “longed for her daughter and her son, the sounds of their voices, the strength of their arms, and the loving condescension of their hearts” (my italics), and yet, when she was with them, she found them to be “attentive, dutiful, insufficient.” In her present diminished state, “it was wearing to be around other people. That was something she realized more and more. People you love, they wear on you, too.”

The novel encompasses three generations, and some of the most winning scenes involve Daniel’s two daughters, Ruby and Cora. Ruby, particularly, is a memorable character: a precociously brainy, pretentious girl who is very much in step with the moment. Cora announces blithely that there is a transgender student in her class: “‘Sometimes people get born in the wrong bodies,’ Ruby explained to her grandmother.” (A recurring comic thread in the book is that Molly, thinking she had done an audacious or at least controversial thing by falling in love with a woman, can’t seem to shock her son or her nieces, who are blasé about these matters.)

Ruby decides to embrace her Judaism, in opposition to her secular, indifferent parents, and to go through with a bat mitzvah, “‘I study my Hebrew,’ Ruby said. ‘I go to services. What do you want from my life? I’m very assiduous.’” Her mother thinks: “You are very supercilious…. Put that in your adolescent vocabulary book.” But Ruby remains appealing, and in any case continues the Bergman female pattern of immersing herself in old photograph albums, just as Joy was a conservator of tenement relics and Molly an archaeologist. A charming conversation ensues between the twelve-year-old Ruby and her aunt Molly, who elsewhere thinks of her as “that little pedant.” Ruby is explaining her fascination with the past to Molly:

“Cora’s scared of dead things. But I don’t see why. They’re dead. I don’t mind them. I like to know that things happened before I came along. I don’t know why, but I do.”…

“Maybe it helps you realize that things will come along after you, too.”

“I think I’m too young to think that.”

Ruby, the wise child, knows she is too young to embrace the prospect of mortality, while Joy, Molly, and Daniel have no choice but to do so. They are all facing death, in different ways, and the sad part is that this realization isolates rather than unites them. Joy thought:

Her children lived in some other world, one that she could see but had left behind, like the wake of a ship. Their lives foamed and splashed while she hurtled forward, away from them, but toward nothing. Well, toward something, and they all knew what that something was.

Though there is grieving all around for Aaron, each is locked in a suffering contingent on their placement in the arc of longevity, and the generation gap is finally too large to bridge. “Daniel and Molly were not old enough, not lonely enough, not cold enough to understand.” Joy thinks: “Someday they would understand. They would feel sad the way she felt…. If only everyone could be old together.” A utopian dream, and of course an impossible one. What is acutely demonstrated in the book is that everyone can at least be solitary and misunderstood together, at the same time, possibly, offering each other a concerned tenderness.

It is an old story, this plot showing the decline of aging parents and the failure of their children to cushion the fall: we have seen it in tragedies like King Lear, or in films like Tokyo Story and Make Way for Tomorrow, though this time there are no villains, no heartless progeny, just the unavoidable common enemy that this well-intentioned crew all face. Appropriately, given that the plot does not pretend to be original, the prose is straightforward and direct, without showing off or striving for linguistic effect. By now, Schine appears so confident in her novelistic powers and wisdom that she can simply cut to the point with epigrammatic insight. There is also less of a need to prove herself funny all the time—just as well, given the gravity of the material.

Still, she provides plenty of wry moments, and the novel’s pungent pathos finally issues from many small, everyday details. We are treated to dozens of shrewd recognitions, such as that Molly “had never really gotten used to living without doormen.” Or “They were squeezed in at the table in the kitchen drinking the house specialty, decaffeinated tea, weak, lukewarm.” Or about Aaron in his senile phase: “He often took on this joshing tone when he was confused.” Or this description of Molly’s directionless son: “Ben Harkavy, bartender and handsome alley cat, the kind that rubs against your leg, then hops a fence and disappears.” Or, finally, Joy quizzing the funeral director: “‘You will have a coatrack,’ she said, ‘in case it rains?’” Such realistic touches thicken immeasurably our sense of the characters’ inner and outer lives, holding a mirror, to borrow Trollope’s phrase, to the way we (or at least some of us) live now.