In his 1996 memoir The Color of Water, James McBride describes a difficult moment of his boyhood in the 1960s. Raised in Queens, along with eleven siblings, by a black stepfather and a white mother (a Polish Jew who had told her children little about her origins), he was sent to predominantly Jewish schools at the insistence of his mother. She was intent on his getting what she considered the best education available, even if she herself had long been cut off from her family and her religious upbringing, ever since marrying an African-American minister and converting to Christianity. But McBride writes:

As a kid, I preferred the black side, and often wished that Mommy had sent me to black schools like my friends. Instead I was stuck at that white school, P.S. 138, with white classmates who were convinced I could dance like James Brown. They constantly badgered me to do the “James Brown” for them, a squiggling of the feet made famous by the “Godfather of Soul” himself, who back in the sixties was bigger than life. I tried to explain to them that I couldn’t dance.

When he finally gives in and launches into his version of the dance, he is momentarily lifted by their apparent enthusiasm but then crushed as he picks up on “the derision on their faces, the clever smiles, laughing at the oddity of it.” This is only one episode in McBride’s winding account of sorting out who he really is in the process of learning about his mother’s hidden life. For a moment, in this narrative of elusive and conflicted identities, James Brown emerges as a clear and unwavering emblem of black identity, a status that Brown affirmed resoundingly with his 1968 hit “Say It Loud—I’m Black and I’m Proud.”

Two decades after his memoir, in Kill ’Em and Leave, McBride returns to Brown, offering along the way further details about his own childhood. He grew up in a house “where food was scarce and attention scarcer, where ownership of the latest James Brown 45 rpm was like owning the Holy Grail.” At that same time, James Brown was living not far away in “a huge, forbidding” twelve-room mansion in St. Albans, “with vines creeping onto the spiraled roof and a moat that crossed a small built-in stream, with a black Santa Claus illuminated at Christmas, and a black awning that swooped down from the front yard in the shape of a wild hairdo.”

Here McBride and his friends would stand on the street for hours and days, hoping for a glimpse of their idol, swapping rumors about Brown handing out money to kids if they promised to stay in school. McBride never got that glimpse back then, although his sister Dotty did knock on Brown’s front door and got the benefit of the Godfather’s advice: “Stay in school, Dotty. Don’t be no fool!”

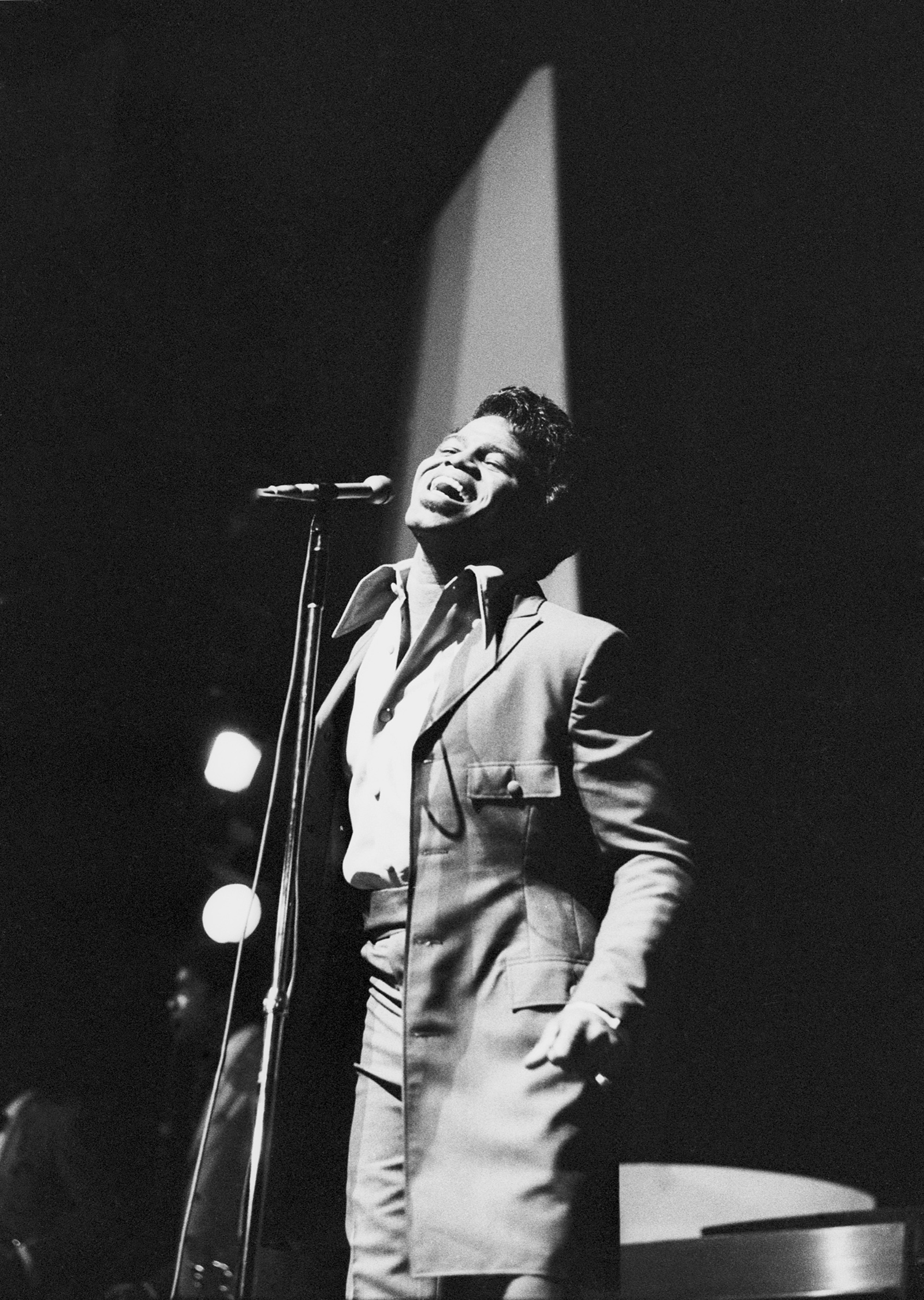

This was the time when the album Live at the Apollo (1963) and the hit single “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag” (1965) had made Brown something more than another pop phenomenon. Even in the era of the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan, and the Motown roster of stars, James Brown established a place that was his alone. In a musical environment given to crossovers and fusions, Brown insisted on being no one but himself, and with the unprecedented Live at the Apollo album—a project he paid for himself because his label (King) saw no commercial potential in a record that would in fact end up on the charts for sixty-six weeks—made himself the center of a hypnotically involving ritual event without breaks or divisions, beginning indelibly with organist/emcee Fats Gonder’s rollcall of epithets—“So now, ladies and gentlemen, it is Star Time, are you ready for Star Time? Nationally and internationally known as the Hardest Working Man in Show Business… Mr. Dynamite, the Amazing Mr. Please Please himself, the star of the show, James Brown AND the Famous Flames!”—through the extended emotional journey of “Lost Someone” culminating in the famous scream, all the way to the exit music that was like a perpetual beginning, “Night Train” with its promise of a rhythmic continuum that could never be interrupted, a train that would always be arriving and never stopping.

It was pure show business and also the closest thing to a religious experience that some young listeners had ever tuned into, even if it was a religion that could swerve (in “I’ll Go Crazy”) into a declaration of single-minded self-sufficiency: “You’ve got to live/For yourself/Yourself and nobody else!” It was not about magic, it was about power summoned up and asserted—power that could not be denied by anyone brought within its field of influence.

Advertisement

This was something the Rolling Stones learned when, having insisted on being the closing act on the T.A.M.I. Show—the 1964 concert film bringing together on the same scarcely credible bill (in addition to Brown and the Stones) the Beach Boys, Marvin Gaye, Chuck Berry, the Supremes, and a good many others—they had to follow James Brown. Fortunately for all of us, Brown’s performance is preserved to provide permanent astonishment.

You might try to break his performance into its components: the percussive exactness of every move and glance; the overwhelming force of his singing on “Prisoner of Love” and “Please, Please, Please,” in which he lets loose cries and howls of passion and suffering while suggesting that this is actually a form of restraint, since there is so infinitely much more kept within; the glide across the stage on one leg, as if his body was made of water, and all the other dance moves that made him such a formative influence for Michael Jackson; the sudden drop to his knees, and then that drop repeated again and again until it seems he could hardly withstand such impact; the rite in which the Flames turn to comfort him in his distress, draping over him the robe that he repeatedly casts off; the final unexpected split just as he is heading toward the wings. But there are no separate parts. It is all one thing, a concentration of energy that makes every other performance on the bill seem approximate. (“When Jagger and the Rolling Stones followed,” McBride duly notes, “they sounded like a garage band by comparison, with Jagger dancing around like the straw man in The Wizard of Oz.”)

The book McBride has written is no nostalgic homage, nor does it aspire to be part of the very large dossier of investigative raking over of the excesses and bizarre turns—the repeated arrests for domestic violence, the troubled relationships with children acknowledged and unacknowledged, the byzantine business deals and concealed caches of money, the peremptory mistreatment of musicians, the furtive angel dust addiction, the circumstances that led to Brown’s two-year imprisonment following a 1988 car chase by police—of a crowded and unimaginably propulsive life. McBride has subtitled it Searching for James Brown and the American Soul, even if it becomes clear early on that the search may end in an acknowledgment of the unfathomable. “You did not get to know James Brown,” Brown’s lawyer tells McBride, “because he did not want to be known.” Later in the book Brown’s longtime manager Charles Bobbit chimes in to the same effect: “Many people claim they know him…. It’s pure bullshit. Most of them don’t know him because he did not let them know him. He didn’t want them to know him.”

There are as many James Browns as people to talk about him: “Brown was crazy. Brown was a genius. Brown was a woman basher. Brown was abused by gold-digging women. Brown was cheap. Brown would give away his last dime.” Multiple versions exist of almost every episode of James Brown’s life, and some of the contradictions can be traced back to the man himself. His autobiography, James Brown: The Godfather of Soul (1986), cowritten with Bruce Tucker, is regarded by McBride and others as filled with deliberate acts of misdirection.

That book does, however, lay down a persuasive and unforgettable image of a boy spending long stretches of time alone in a windowless shack in the middle of a pine forest, whiling away the hours with nothing to do while his father goes out harvesting turpentine:

I don’t think you can spend that much time by yourself as a child and not have it affect you in a big way. Being alone in the woods like that, spending nights in a cabin with nobody else there, not having anybody to talk to, worked a change in me that stayed with me from then on: It gave me my own mind.

What McBride turns up in his search only confirms that solitariness, a wary solitariness that paradoxically found its fullest expression in his ability to give himself so completely in performance as to suggest for his audience a generosity approaching self-immolation.

The scholarship and critical literature on James Brown, by R.J. Smith, Gerri Hirshey, Nelson George, Cynthia Rose, Alan Leeds, Jonathan Lethem, and a throng of others, continue to grow, along with the internal contradictions of a legend to which so many informants have added their bit of information or invention. Kill ’Em and Leave doesn’t set out to be either a full-scale biography or another rundown of James Brown’s musical career—a career encompassing at least seventy-nine albums, 184 singles (of which over a hundred made the charts), and more tours and concert dates and radio and television performances than could ever be enumerated. Discographies and appreciations abound, even if there will always be fresh discoveries to be made. (The extraordinary multivolume compendium James Brown: The Singles, released on the Hip-O label, includes a trove of unfamiliar riches.)

Advertisement

To fully consider Brown’s music is of course a matter of going beyond the man himself to parse the contribution of hundreds of other musicians who participated in the shaping of that music, including brilliant figures like Maceo Parker, Pee Wee Ellis, Fred Wesley, St. Clair Pinckney, Jimmy Nolen, Jabo Starks, Clyde Stubblefield, Bootsy Collins—inventors and innovators in their own right. A large part of Brown’s genius was to find such people and—with whatever relentless and punitive insistence—get such work out of them, at least up to the point of firing them for insubordination or losing them to walkouts when they couldn’t put up with him anymore. “Brown’s behavior toward his musicians,” McBride notes, “is one of his saddest legacies…. Most of them, while respecting his musicality and utter showmanship, disliked him intensely.”

Like so many others of a certain era, my sense of the past is punctuated by the sound of this music, from the primary encounter with Live at the Apollo to the shock of hearing “Papa’s Got a Brand New Bag” for the first time on Top 40 radio, like hearing a hole being torn in the other music on the air to make way for something incomparably more direct and uncluttered, a music with every element laid bare; to submitting for the first time to the gospel exhortation of “Maybe the Last Time,” a record to stir awe and trembling; to the sweet experience of dancing over and over to “There Was a Time” on Live at the Apollo, Volume II because it was the first dance record that seemed to defy the idea that it ever had to end; and down the years to the moment of waking alone on a cold winter morning in 1974 to the sound of my radio alarm and hearing for the first time—breaking into it somewhere in the middle—“The Payback,” the rejected main title song intended for the blaxploitation movie Hell Up in Harlem and released as a single that cut through all surrounding noise, all at once heavy and implacable and exhilarating, and incidentally providing some much-needed heat for my walk-up apartment: “I want revenge! I want revenge!”

Yet I don’t associate James Brown’s music with the past. Other records of that day may carry unavoidably a freight of nostalgia, of the pangs of frustration and loss, until it seems that the only way to be free of the past is to just stop listening to those old sides. But James Brown’s music escapes that trap. It inhabits a permanent present, insists on it (“Stay on the scene!”), clearing a space and always offering up surprise, as if each accent and interjection were only now being invented, in the moment of paying heed. Having progressively stripped away song structure, melody, even chord changes, it brings everything down not to simplicity but to an ever more complex interchange of accentuations, “an intricacy of shifting parts” in McBride’s phrase, or what a poet friend of mine identifies as “Pythagorean number magic.”

Kill ’Em and Leave skips lightly over many important public episodes and resists any orderly biographical timeline; anyone looking for that kind of treatment might well turn to R.J. Smith’s superb The One: The Life and Music of James Brown (2012). McBride is after something more oblique and circuitous. He moves back and forth in time, revisits the same scene from different perspectives. He’s up-front about making himself a character in his book, telling us disarmingly that his most compelling motive for undertaking a book about James Brown was to make some money in the wake of a bad divorce. (“I needed the dough, plain and simple. The ex-wife dropped the hammer.”)

It’s very much a story about how he got the story. At every point we’re kept aware of where he is, what he’s going through in the midst of a conversation, what past scene or parallel reality he’s reminded of by the people he encounters. He doesn’t hesitate to interrupt his story to rail against the scurrilous scandal-mongering of the Internet, the decline of print media in America, or any one of the thousand ways a musician, most especially a black musician, can be shortchanged, neglected, and written out of history.

He devotes many indignant pages to detailing the nightmarish process by which Brown’s estimated $100 million fortune—most of it earmarked in his will for the educational needs of poor children in Georgia and South Carolina—has been tied up and dissipated in endless legal machinations. McBride is a musician as well as a writer, and his prose has the improvisatory flow and rhythmic freedom of a live voice urgently conversing, by turns impassioned, funny, rueful, angry, exasperated. As for his method, it’s a matter of going to places where Brown lived—places like Barnwell, South Carolina, in the Savannah River Valley, where he was born in 1933, or the United House of Prayer in Augusta, Georgia, where he was initiated into the energies of gospel music (the foundation of his own music) by his boyhood friend Leon Austin—and getting to know people who knew him, Austin and his wife Emma very importantly among them.

Like Citizen Kane, the book is a series of encounters with people offering up their particular sense of someone who isn’t there anymore. We get Brown at one remove, sighted from different angles, filtered through the lives of people like his first wife, whom he married in Toccoa, Georgia, where he settled at age eighteen after serving three years in a juvenile prison for stealing some auto parts; the guitarist Nafloyd Scott, the last surviving member (now dead) of Brown’s original group the Famous Flames, with whom in 1956 he recorded his breakthrough hit (for a long time to follow it was his only hit), the eternally mesmerizing “Please, Please, Please”; Alfred “Pee Wee” Ellis, the saxophonist who as musical director was the principal shaper of the James Brown Orchestra into a vehicle for the ever more angular, polyrhythmic, unheard-of funk of such records as “Cold Sweat” (1967) and “Mother Popcorn” (1969), and who when asked to talk about James Brown says, “Can’t we talk about something else?”

Al Sharpton, who made Brown’s acquaintance when he was a seventeen-year-old Pentecostal preacher and quickly became his most favored protégé, fills in a good part of the later years. Sharpton traveled with Brown and modeled himself after him: “He dominated every room he walked in, and I’m one of the few people who’s been in the room with him in the White House with Reagan and Bush, and in his jail cell.” Sharpton stayed close during the troubled times that followed the era of Brown’s greatest success, the times “when Brown was broke, his business collapsing, his private jets confiscated, his radio stations gone, the IRS breathing down his throat,” all the way through to a late-life drug habit, a third marriage spinning into violence, and the car chase that landed him in State Park Correctional Institute in Columbia, South Carolina, in the same year that he released the hit single “I’m Real,” with its challenge to the imitators who for years had been sampling and remixing his beats and vocal riffs: “All you copycats out there,/Get offa my tip!…/Nobody out there good enough/To take the things I have.” Following his early release, Brown got right back in the game and kept touring to the end, performing an estimated eighty-one shows in the last year of his life.

And after Brown died on Christmas morning 2006, when he was seventy-three years old, it fell to Sharpton to transport the body from Augusta to New York, for a memorial service at the Apollo, in the back of his van when other means of transportation fell through. It’s Sharpton who gives the book its title, as he relates one of Brown’s enduring maxims: “Kill ’em and leave, Rev. Kill ’em and leave.” Or, in a variant of the same principle: “Don’t let folks get too familiar, Rev. Don’t stay in one place too long. Come important and leave important.” Brown’s son Terry shares a related bit of parental wisdom: “He trained you to keep it tight. Don’t talk. Do. And watch the money.”

The big visible events of such a career can hardly suggest the life lived between the public moments. What McBride is looking for as he sounds out those closest to a man who let few get close to him is that unseen life. What he finds is often a labyrinth of hiding places, some of them literal, like the countless repositories where he liked to hide money (“in vases, safes, buried under trees and in gardens, hidden in the floorboards of a car, under rugs in far-distant hotels that he’d visit every year while touring”), some of them embodied in the patterns by which he compartmentalized the people and activities in his life, keeping the parts separate and giving himself the freedom to move when and where he wanted. Sharpton, again: “He was so in control of himself. I never met anybody that had that kind of controlling presence.”

Looking for the man, McBride finds the place where the man came from, as he retraces Brown’s steps in Barnwell and Toccoa and Augusta and Beech Island, South Carolina, where in the 1980s Brown built a house for himself that would become his final compound and hiding place. Beech Island (not an actual island) is in sight of the Savannah River Nuclear Site, an immense bomb-making facility built in the early 1950s. The construction of the 310-square-mile site required the demolition of six towns and the relocation of thousands of people, the majority of them black sharecroppers. One of the towns destroyed was Ellenton, where members of James Brown’s extended family had lived as far back as the aftermath of the Civil War. McBride writes caustically about the way this history of an erased town so starkly pits ultimate power against ultimate powerlessness. He describes Brown at the end of his life, pointing to the giant antenna towers of the nuclear site, and confiding in his manager: “You see those towers, Mr. Bobbit? The government’s listening to me. They can hear everything I say. They’re listening through my teeth.”

James Brown came back to the South because after a decade in New York he couldn’t feel at home and couldn’t trust the people with whom he did business: “Down home, I know who I’m dealing with.” McBride’s acute sense of the hidden, or not so hidden, pressures of that southern world—“a South where blacks and whites lived as a kind of dysfunctional family, with a familiarity that is hard for outsiders to understand”—pervades the most eloquent pages of his book. Writing about James Brown, he ends up writing insistently about the South:

Brown was a child of a country in hiding: America’s South…. You cannot understand Brown without understanding that the land that produced him is a land of masks.

A land of masks and of fear, the fear that Charles Bobbit asserts was the secret driving force behind Brown’s trajectory, fear of that white power that was the encompassing force in the scenes of his boyhood as it was in the record business and the IRS and the criminal justice system. To ward off that threat he created the most complex system of defense imaginable, a parallel reality built, for as long as he could sustain it, on almost inconceivable reserves of self-discipline and control. At a personal cost that McBride’s book helps to gauge, James Brown invented James Brown.