The modern state of Turkey has known three coups in which its military forces took power, in 1960, 1971, and 1980. In addition there was the coup of 1997, when the generals sat down with an Islamist prime minister, Necmettin Erbakan, and forced him to resign, making way for a secularist successor. These interventions were designed to protect the secular, European identity of the republic that was established by Mustafa Kemal Atatürk in 1923 from the perils of Islamism, communism, and political violence. They were all animated by an ideology known as Kemalism and they were all followed by repression. Kemalism espoused the principles of “republicanism, statism (in economic policy), populism, laicism, nationalism, and reformism,” which did not exclude authoritarian measures to maintain the government’s power. The 1960 coup led to the execution of the deposed prime minister, Adnan Menderes, and the 1980 coup to imprisonment and torture on a grand scale. After each intervention democracy was suspended and the leaders of Turkey’s political parties tried to figure out how to avoid the next one.

The coup that some Turkish officers launched on the evening of July 15 differed from these earlier interventions—aside from the obvious fact that it failed. It was the indirect result of a purge of secular-minded Kemalist officers that has taken place within the military over the past decade or so, and their replacement by Islamists. The coup on July 15 seems to have been the first in Turkey aimed at promoting an Islamist ideology. The plotters were said by the government and by many others to have acted in the name of Fethullah Gülen, an Islamic preacher and educator who, while living in exile in Pennsylvania, has carefully distinguished himself from other Islamists by his pro-Western, ecumenical message, which has been disseminated through many schools and colleges in Turkey and elsewhere, and in a variety of publications. The target of the plotters was President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan and the Justice and Development Party (AKP) government he served as prime minister between 2003 and 2014—and which he continues to dominate almost completely.

Erdoğan and his AKP are Islamists also. They formed an alliance with the Gülenists in the late 2000s and the beginning of this decade and drove many Kemalists out of the military and other institutions. In 2013 Gülen broke with Erdoğan. Having largely achieved their aim, Turkey’s two dominant Islamist groups turned on each other in a vicious struggle over state patronage and control of education and much of the private sector. Many of the Gülenists were driven by religious conviction. Gülen is regarded by many of his followers as a friend of God.

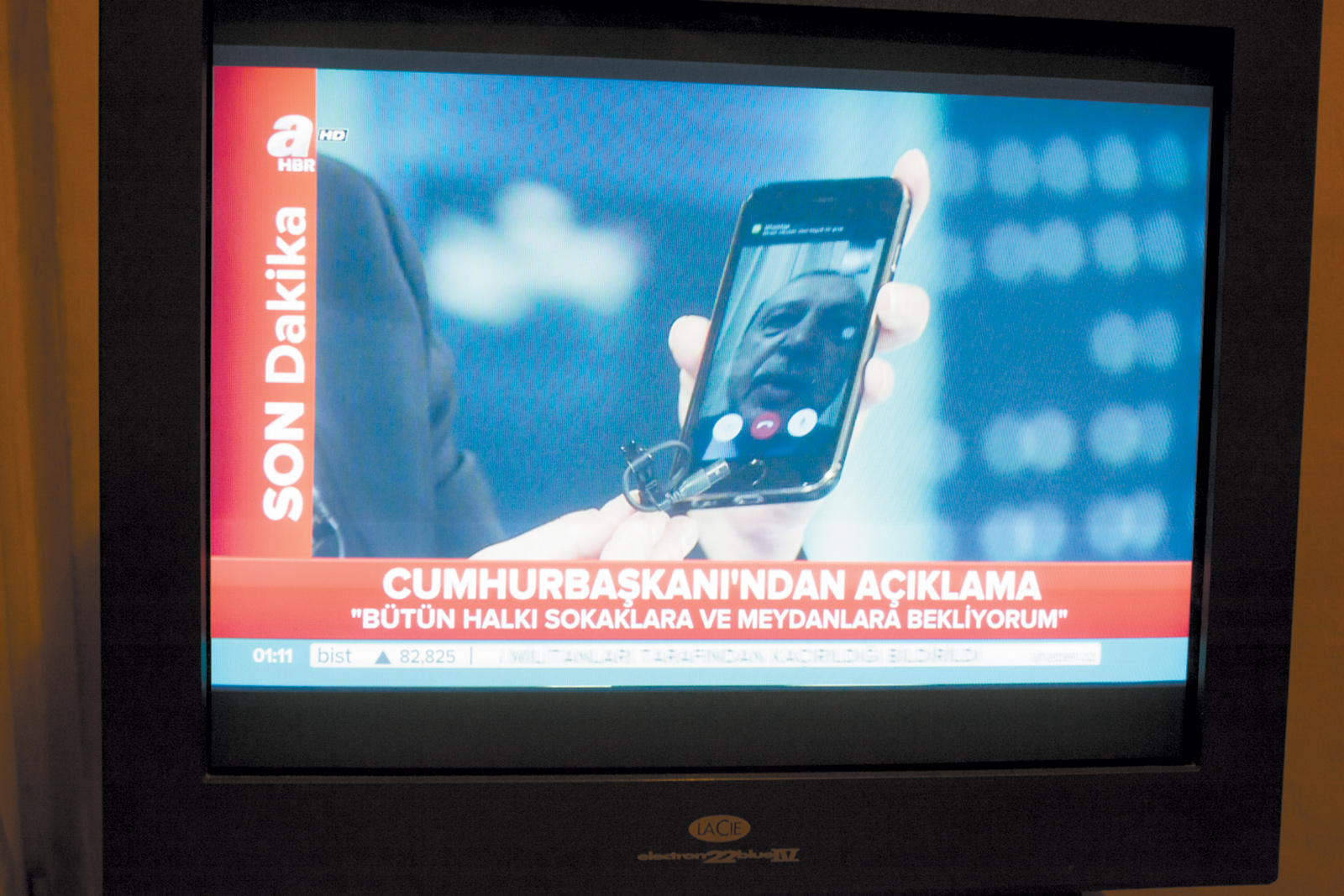

On the evening of July 15 some Turkish officers attempted to seize strategic government offices, capture or kill Erdoğan, and install a junta that they called the “Peace at Home Council.” This plan was thwarted as a result of leaked intelligence and Erdoğan’s call to Turkish citizens to take to the streets. Millions of Turks did so and many showed extraordinary bravery in resisting the rebels.

The government responded to the botched coup with one of the biggest purges in Turkish history. During the following days some 13,000 military personnel—including 40 percent of the country’s generals and admirals—were arrested or dishonorably discharged, and more than 60,000 civil servants were fired or suspended. Some 6,000 public employees were arrested, dozens of Gülen-affiliated schools and universities were closed, and around 8,000 private companies were put under investigation. Senior AKP people who used to have close relations with the Gülenists also came under attack. On August 3 an Istanbul lawyer brought a case against four former ministers on the grounds that they had “infiltrated members of the [Gülen] organization into the state apparatus.”

Earlier efforts by the AKP to subordinate the armed forces to civilian politicians are now being pursued more intensely than ever. Under the state of emergency that Erdoğan declared on July 21, decrees have been issued to consolidate staff colleges into a National Defense University, relocate army bases away from the cities, and give civilians a majority in the Supreme Military Council, the body that decides promotions.

For all the decisiveness of the government’s response to the coup, and the near-unanimous view among Turks that the Gülen movement was involved, it is still difficult to trace exactly what happened on July 15. The Gülen movement is secretive, compartmentalized, and claims to be a force only in education and matters of the soul; from his home in Pennsylvania its bookish, avuncular, mystically inclined founder vigorously denies any involvement in the coup, and the US government has so far resisted Turkey’s request to extradite him.

Advertisement

Attempts to dramatize events as the product of a single, dastardly conspiracy are common in Turkey, but they should be treated with caution. Conspiracies such as the recent coup attempt are presented as neat and all-encompassing, but such a view is at odds with the slapdash, fissiparous reality of Turkish life. Sometimes—as the Gülenists have shown in the past themselves—there is no conspiracy at all.

In August 2013, Gülenist judges jailed 275 military officers and others for membership in a terrorist organization called “Ergenekon.” An appeals judge later ruled that no such group existed; the case had been fabricated as part of the joint campaign by the Gülenists and the AKP to drive Kemalists out of the military. In a related case, more than 300 serving and retired members of the armed forces were jailed for plotting a coup; that case also was thrown out on appeal.

Strange though it appears, Kemalists may have taken part in the failed coup. This was suggested by the name that the putative junta chose for itself—“Peace at home, peace in the world” was one of Atatürk’s best-known aphorisms. A respected analyst of the Turkish military, Gareth Jenkins of the Washington-based Institute for Security and Development Policy, has written that some of the arrested officers are admirers of Turkey’s secular founder. Kemalists and Gülenists both objected to Erdoğan’s now-suspended efforts to make peace with guerrillas from the Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK). Both share Atatürk’s antipathy to Kurdish aspirations. It seems plausible to some observers I talked to in Turkey that there could have been an opportunistic alliance between the military and Gülenists to get rid of a president who they thought might at any time return to negotiations with the Kurds.

Since July 15, many of the arrested officers have given statements to state prosecutors incriminating themselves or others, and these have been leaked to the press. By closely analyzing their statements, the government’s accounts of events, and investigations by Turkish journalists (who in many cases are simply regurgitating what their government contacts tell them), one can try to reconstruct what happened, even though the information comes from a limited number of people and many of the accounts are being voiced, under pressure, in an echo chamber. Still, from what we know so far, the coup seems to have unfolded along the following lines.

Originally, a coup was prepared for the early hours of July 16, when most Turks would be asleep, but when the plotters learned that their plans had leaked, they went ahead on Friday, July 15. The first senior official to have suspected that a coup was imminent was Hakan Fidan, the head of Turkey’s spy agency, who learned about it on the afternoon of July 15. His failure to inform his political masters immediately has been much criticized. At around 9:30 PM two bridges over the Bosporus were blocked by tanks. General Hulusi Akar, the chief of the general staff, was removed from his headquarters by force in Ankara and taken to Akıncı air base, northeast of the capital—to which other senior officers, some of them kidnapped from a society wedding, were also taken. By 10:30 PM the website of the general staff was announcing that the armed forces had taken over the country. An e-mail to the principal ministries announced the imposition of martial law, the closing of borders, and the establishment of courts to try “traitors to the nation.”

Well into the evening of July 15, President Erdoğan, who was on holiday in the resort of Marmaris, seems not to have appreciated the seriousness of events. It was only at 12:26 am on July 16 that he issued an appeal via a smartphone for people to come into the streets to oppose the plotters. Some twenty minutes later an airborne team of putschists stormed his hotel with orders to bring him to Akıncı. But by that time the president was on his way to Istanbul, and his appeal was being amplified through Twitter, WhatsApp, and the more traditional medium of mosque loudspeakers.

During the next few hours, as millions of people responded to the president’s call, not only was the coup turned back but the accumulating stories of heroic action against it formed the backdrop against which politics are now playing out. The plotters made determined efforts to neutralize Turkey’s principal civilian and military institutions and destroy the government’s morale. From the base at Akıncı, helicopters and F-16s attacked the headquarters of both Turkish intelligence and Turkey’s antiterror police (in which almost fifty people were killed), as well as the parliament building, whose roof was damaged. In Istanbul, soldiers occupied the mayor’s office and the control tower at Atatürk Airport. The ruthlessness of the rebels was exemplified by a sharpshooter who climbed a stanchion of one of the Bosporus bridges, from which he picked off civilians before eventually being shot.

Advertisement

The plotters apparently expected much less opposition than they met. In Ankara civilians were crushed after lying down or swerving their vehicles into the path of advancing tanks, while at Cengelkoy, on the eastern shore of the Bosporus, eighteen people were killed and many more were injured as loyalists battled successfully to stop army units from taking control of a strategic coastal road. Ordered by his commanding officer to fire into the crowd, one Turkish soldier cried, “I’m not a traitor!” and discharged his pistol into his own head.

Across Anatolia, in towns and cities and in military bases, similar confrontations were taking place on a smaller scale. In Sirnak, in the Kurdish-majority southeast, three hundred putschists surrendered after a struggle with loyalists, while farmers near Akıncı set fire to their crops in order to impede the rebels. The AKP prime minister, Binali Yildirim, was shot at while racing back to Ankara from Istanbul. Parliament met in an emergency session under bombardment.

At 2:50 am on July 16 Erdoğan’s plane was able to land at Atatürk Airport in Istanbul, where he was greeted like a conquering hero. It was clear that the rebels had not achieved their main objectives and that the military was mostly loyal. By 7:00 am the coup was over.

All told, more than 240 people were killed resisting the putschists, and there were well over two thousand injuries. According to the Turkish general staff, 8,500 men, or 1.5 percent of the country’s military manpower, were involved in the uprising, though the fact that so many generals and admirals were taken into custody suggests that some are suspected of complicity, or more likely of malign neutrality and fence-sitting. If the coup had not been launched earlier than scheduled, allowing loyalists to react against it, it is likely that a much larger proportion of NATO’s second-biggest military force would have gone over to the plotters.

For the millions of Turks who openly celebrated the coup’s defeat, July 15 was a vindication of civilian, democratic politics over what might have been the sanguinary nightmare of military rule. Had Erdoğan been arrested, civil war would likely have followed, and there is no reason to assume that the Peace at Home Council established by the military plotters would have been any less brutal than the junta that ruled after 1980.

After July 15 Turkey’s usually poisonous internal politics gave way to rare cross-party cooperation, and on August 7, when millions gathered for a “Democracy and Martyrs’ Rally” in Istanbul, Erdoğan shared a platform with the leaders of the center-left Republican People’s Party and the right-wing Nationalist Action Party (not, however, with Parliament’s third-largest party, the pro-Kurdish People’s Democracy Party, which the president now ostracizes, citing its links to the PKK). As a gesture of unity, the notoriously touchy president has even withdrawn thousands of defamation suits filed in his name.

The international reaction to the coup was important for the Erdoğan government, especially since relations with the West have soured over recent years. In return for money and the promise of visa-free travel for Turkish citizens, the EU, following negotiations led by Angela Merkel, is using Turkey as a kind of sponge for soaking up Syrian refugees, while paying lip service to the fiction that Turkey remains a serious candidate for membership in the EU. Turkey now has more than 2.5 million Syrian refugees in its camps. The priority for the US is to maintain Turkey’s cooperation in the fight against ISIS. American jets and drones use the Turkish air base of Incirlik to launch attacks and make reconnaissance sorties over Mesopotamia.

A visitor to Turkey this summer would soon conclude that July 15 was as traumatic an experience as the September 11 attacks were for the United States or last November’s terrorist attacks were for France. The Turks felt that they did not receive anything like the international support they had a right to expect. Indeed, a prevailing belief in Turkey is that the US—Turkey’s NATO partner since 1952—was in some way involved.

On the night of July 15, when the outcome of the coup was still in doubt, John Kerry, the US secretary of state, restricted himself to calling for “stability and peace and continuity”—hardly a ringing endorsement of an ally fighting for its life. On July 28, James Clapper, director of national intelligence, expressed regret that the arrest of Turkish generals who were allies in the war against ISIS would “set back our cooperation with the Turks.” Gülen’s presence in the United States (where he has been since 1999, though he is not a US citizen), and the fact that the Incirlik air base—shared with the US—was used for refueling rebel aircraft, have further strengthened Turkish suspicions that the US was either behind the coup or had foreknowledge of it—allegations that the US ambassador to Ankara, John Bass, has been trying to dispel.

European Union politicians seemed less concerned for the victims of the coup than about the possibility that Erdoğan would try to impose an out-and-out dictatorship in the name of national security. The EU’s foreign policy chief, Federica Mogherini, warned that Turkey needed to “respect democracy, human rights and fundamental freedoms,” while Jean-Claude Juncker, the president of the European Commission, observed that after the recent events Turkey was “not in a position to become a member [of the European Union] any time soon.” Almost alone among senior Europeans, the former Swedish prime minister Carl Bildt lamented that no senior EU diplomat had thought to visit Turkey to show support for “an accession country facing the gravest threat to its constitutional order yet.”

Erdoğan has contrasted Europe’s lectures on human rights with the prompt and unqualified support he received from Russia and Iran, and he has excoriated the Americans for “taking sides with the coup plotters.” The president’s senior adviser Ibrahim Kalin was no doubt voicing his master’s suspicions of the West when, referring to Western nations generally, he tweeted that “had the coup succeeded, you would have supported it, like in Egypt.” This was a reference to the West’s apparent relief at the coup d’état in 2013 against the elected Muslim Brotherhood government of Mohamed Morsi, an ally of Erdoğan.

It is a long time since Obama and other Western leaders held up Erdoğan and his regime as an example of a pluralism that could solve the perennial riddle of Islam and democracy. Erdoğan has spent the past few years trying to gather more power for himself, though his preferred vehicle to achieve this, an executive presidency, has so far eluded him. He has also cracked down on domestic dissent and, last year, revived a pitiless war against the PKK.

Erdoğan’s assertive policies have led to a damaging entanglement in the Syrian civil war, of which the most important consequences are the presence of the 2.5 million Syrian refugees in Turkey and, beginning in July 2015, a series of deadly bombings by ISIS. Erdoğan opposes both Syrian President Bashar al-Assad and the PKK’s Syrian Kurdish allies, who have been effective fighters, and this in the past led him into tacit cooperation with ISIS, for which Turkey was a conduit for arms, medical aid, and recruits. America did not hide its frustrations at Erdoğan’s Syria policy, and it seems plausible that in the period before the attempted coup the US cooperated with Gülenist elements in the military to bring Erdoğan’s long-denied cooperation with ISIS to light.

Many in Turkey believe that the West once again favors generals that seize power and not Islamists who are elected to it. To these Turks it makes perfect sense that their pro-Western message would make the Gülenists preferable to Erdoğan in American eyes.

Turkey’s relations with the EU are unlikely to improve soon. The refugee arrangement seems likely to unravel as a result of Turkey’s failure to enact legal reforms—such as rewriting antiterror laws—that the European Union has demanded in return for visa-free travel. Meanwhile the Americans have to deal with an ally who impugns them in public and whose anti-Western supporters have urged him to withdraw from NATO and explore an alliance with Russia. (This admittedly would be a difficult feat to pull off, as Turco-Russian relations have yet to recover from Turkey’s downing of a Russian jet that allegedly strayed into Turkish airspace last November, itself a product of the two countries’ opposing positions in Syria. Still, Erdoğan’s cordial visit to Vladimir Putin in St. Petersburg on August 9 may have indicated a narrowing of differences.)

In fact, there have been signs since the coup that, in return for cooperation from world powers in preventing the Kurds from setting up a new state on its southern border, Turkey is beginning to change its Syria policy. Amid rumors in the Arab media that Turkey and Syria have been engaged in behind-the-scenes negotiations, the prime minister, Binali Yildirim, has hinted broadly that Turkey would not prevent a peace deal under which Assad was allowed to stay on during a transitional period. On August 24, Turkish and American forces launched a major offensive against Islamic State militants, including a land invasion by Turkish tanks. The joint aims of the two forces seem to be to sever an important ISIS supply route and limit the Kurds’ territorial ambitions on Turkey’s southern border.

The Turkish government has made it clear that an improvement in relations with the US is contingent on the extradition of a man they regard as a terrorist leader, although John Kerry has said that extradition must be approved by a court and has given no sign that it could happen. Most people who follow Turkey closely—including Western ambassadors I have spoken to—are prepared to believe that Gülen’s followers were involved in the events of July 15. I often heard the theory that the coup was precipitated by rumors that Gülenist officers were about to be purged from the military.

Pinning responsibility on Gülen himself is another matter, however, although efforts are being made to do so. John Bass, the US ambassador to Turkey, has warned in interviews with Turkey’s fervid press that leaked witness statements incriminating the exiled preacher may be inadmissible in an American court. General Akar, for instance, has said that one of the officers who kidnapped him offered to put him through by phone to Gülen, while the mainstream newspaper Hurriyet reported that before the coup a senior Gülenist visited sympathetic officers at Akıncı and delivered “Gülen’s orders” along with a fatwa, or legal opinion, authorizing Erdoğan’s overthrow.

The Gülenists are powerful beyond the more than one thousand private schools that they have founded in some 120 countries—including the US. The scale of their alleged infiltration of Turkey’s vital institutions is illustrated by the fact that the post-coup detainees include the general manager of Turkey’s leading petrochemicals company, hospital surgeons who carried out some of the country’s first transplant operations, and Erdoğan’s own aide-de-camp. An employee at the Istanbul office of a major European investment bank told me that his Gülenist colleagues had been absent since July 15. “Everyone knew who they were,” he said. “They were often the most capable, spoke the best English, and were the best equipped to deal with foreigners.”

Furious reprisals have been underway since July 15. Human rights are being trampled by a state that on July 21 formally suspended the rights of its citizens to freedom of movement, expression, and association, which are central to the European convention on human rights. (France did the same after the November attacks.) The loyalist press condemns judicial suspects out of hand as “traitors” and Erdoğan has said that he would approve the reintroduction of capital punishment if parliament were to pass a bill to that effect. Left-wing teachers and liberal journalists—who have no plausible connections with Gülen—have been arrested on flimsy suspicions of involvement in the coup, and dozens of media outlets and publishing houses have been shut down. On July 24, Amnesty International announced that it had credible evidence that detainees were “being subjected to beatings and torture, including rape, in official and unofficial detention centres.”

The fury could well abate, especially if the state of emergency is allowed to lapse after its initial three-month period. If it does not, quite apart from the damage done to Turkey’s economy, which has experienced a sharp flight of foreign money following the coup, there is another structural risk. By repressing a movement whose sympathizers are estimated to number in the millions, and whose financial and other assets may now be distributed among Erdoğan’s allies, the government may breed a vivid sense of injustice that will cause a broad reaction.

An important question raised by the July 15 coup concerns Turkey’s strategic position. How will the hollowing out of the army and of other institutions—Turkey’s spy agency may be next—affect the country’s ability to fight armed Kurdish rebels and ISIS cells? Will the prestige that now attaches to Erdoğan as a gazi, or holy warrior, advance his long-term plan to gather more power? Neither of these questions can as yet be answered with any certainty. Nor can the question of whether July 15 will be remembered as the moment when Turkey turned decisively away from the West. What is certain is that on that night the once-mighty army shed much of the prestige it has enjoyed since Ottoman times, and Turkey, although still subject to autocratic rule, finally became a civilian state.

Research for this article was supported by the Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting.

This Issue

September 29, 2016

Maya Lin’s Genius

The Heights of Charm

How They Wrestled with the New