Wisława Szymborska (1923–2012) was awarded the Nobel Prize in 1996, but she came of age in the late 1930s, in Poland; and to judge by the evidence in Map: Collected and Last Poems, her wit and judgment were sharpened and her disposition of charity deepened by the war years. Yet Szymborska was always an artist in a broader sense than personal history or world history allows. She worked, early on, as an illustrator of children’s books, and this detail of her experience seems pertinent; it goes with her ability to seize an image for immediate use, a sixth sense for the moment when a pause is needed, or when the reader’s patience for indicative statement has run out. She was an artist of eye and ear (both considered as parts of the mind). And she was gifted with the responsive humor and tact that can make a person seem a peer, a familiar presence, far outside her native environment.

As we are made to feel throughout this generous volume, Szymborska addresses her readers with the candor of an unheralded neighbor—someone we never met but were always curious about when we saw her passing by. The impression of familiarity is ordinary and at the same time magical; and it has been strengthened by some of the most effective and colloquially vigorous translations of poetry in modern English. Perhaps that is all that ought to be said by a reviewer who does not read Polish. In these versions by Clare Cavanagh and Stanisław Barańczak, Szymborska’s poems seem the direct transcriptions of a person speaking her thoughts without any intervening medium.

Her poems loiter with intent and pick out occasions for wonder in the most taken-for-granted animals, minerals, or vegetables. What is there to say about an onion? It is white and fibrous and uniform, layer after layer the same from the outside in. The onion may appear to be a monotony void of tint or texture. Szymborska denies this and asks us to imagine, on the contrary, that it might be human innards that deserve reproach:

Our skin is just a cover-up

for the land where none dare go,

an internal inferno,

the anathema of anatomy.

In an onion there’s only onion

from its top to its toe,

onionymous monomania,

unanimous omninudity.

The redundancy of the acrid bulb and root was an unlooked-for elegance, after all.

An element of sheer play is prominent in Szymborska—she wants to surprise herself—though Diaghilev’s “Astonish me!” would strike her as a pretentious demand. Her wit is never merely verbal, and her perceptions seldom shape themselves into an aphorism or fling off the sparks of an epigram (nor does one want them to). A favorite subject is the chance encounter—“happenstance,” as she calls it—a good word for the welcome intrusions of life, the moments that cannot be planned but are as rewarding as happiness is supposed to be. Her love of the everyday phenomena of experience, for their own sake, is brought forward in “Moment” with the unguarded freedom of earnest statement:

Woods disguised as woods alive without end,

and above them birds in flight play birds in flight.

This moment reigns as far as the eye can reach.

One of those earthly moments

invited to linger.

Invited by whom? If Szymborska meant that she issued the invitation, she would have said so. It is rather as if life, the master of appearances, had laid out the scene, an invitation to the onlooker.

“No Title Required” speaks of a similar moment, but with scope for meditation on why it should interest the poet:

It has come to this: I’m sitting under a tree

beside a river

on a sunny morning.

It’s an insignificant event

and won’t go down in history.

It’s not battles and pacts,

where motives are scrutinized,

or noteworthy tyrannicides.

Here as elsewhere in Szymborska’s work, a tacit argument is unfolding behind the scene. History assigns no significance to the experience she describes; and what index other than history could serve to classify the events of our lives? “And yet,” she replies, “I’m sitting by this river, that’s a fact.” The moment is irreducible, it has a past, and so does the author, and so does the scene; and you can name the tree (a poplar): it has been there for years, and the path was beaten by the footsteps of many travelers; and a wind blew the clouds in, and soon will blow them away.

Still, the moment is a thing in itself (Szymborska says), without event, yet “just as grounded, just as definite” as any world-historical crossroads. “An- niversaries of revolutions may roll around,/But so do oval pebbles encircling the bay.” The poem therefore continues to regard with aplomb the things that are passing:

Advertisement

So it happens that I am and look.

Above me a white butterfly is fluttering through the air

on wings that are its alone,

and a shadow skims through my hands

that is none other than itself, no one else’s but its own.

When I see such things, I’m no longer sure

that what’s important

is more important than what’s not.

Szymborska has great consistency of tone and temperament. Her collected poems establish the integrity of a career that spanned half a century without any need for a prose trot, subheadings, or captions to prove an argument. If a change is noticeable in the later poems, it comes from a relaxed readiness to watch herself as a poem unfolds, or sometimes as it fails to crystalize. She now has less need of an occasion, a subject clearly marked: but there is no loss of energy.

One of the best poems of this fluent and tentative kind, “Perspective,” yields a street scene observed by the poet from a window. A man and a woman have passed each other like strangers, but she thinks she can recognize by their postures that they were lovers. Or is this a fancy? In fact, they passed each other without any gesture. Maybe they were not the people she thought they were; but she is tempted by the fancy—because “just for a moment” it held her—and “I try in this chance poem/to persuade you, oh readers,/it was sad.”

A sadness that many poems return to comes from the relationship of the living to the dead—above all, the impotence of both the living and the dead to know what they should know in order to give enlightenment or consolation. “The Letters of the Dead” is a great poem spoken in a single breath:

We read the letters of the dead like helpless gods,

but gods nonetheless, since we know the dates that follow.

We know which debts will never be repaid.

Which widows will remarry with the corpse still warm.

Poor dead, blindfolded dead,

gullible, fallible, pathetically prudent.

We see the faces people make behind their backs.

We catch the sound of wills being ripped to shreds.

The dead sit before us comically, as if on buttered bread,

or frantically pursue the hats blown from their heads.

Their bad taste, Napoleon, steam, electricity,

their fatal remedies for curable diseases,

their foolish apocalypse according to Saint John,

their counterfeit heaven on earth according to Jean-Jacques…

We watch the pawns on their chessboards in silence,

even though we see them three squares later.

Everything the dead predicted has turned out completely different.

Or a little bit different—which is to say, completely different.

The most fervent of them gaze confidingly into our eyes:

their calculations tell them they’ll find perfection there.

Such a calculus of “perfection” belongs properly to the dead. The living, if we are free enough and alive enough, must recognize that perpetual improvement is only a confidence trick we play on ourselves.

Some of Szymborska’s most fully achieved poems carry titles that show her variety almost as well as quotations can: “Commemoration,” “Atlantis,” “The Monkey,” “Rubens’ Women,” “I am too close…,” “A Film from the Sixties,” “Report from the Hospital,” “Dinosaur Skeleton,” “Interview with a Child,” “Thank-You Note,” “The Old Turtle’s Dream,” “The Onion,” “Archeology,” “View with a Grain of Sand,” “On Death, Without Exaggeration,” “Our Ancestors’ Short Lives,” “Sky,” “Cat in an Empty Apartment,” “Parting with a View,” “Slapstick,” “A Little Girl Tugs at the Tablecloth,” “A Few Words on the Soul,” “Teenager,” “Foraminifera,” “To My Own Poem.” And then there is the poem about a snapshot of Adolf Hitler as a toddler.

How his parents love him! How cute is that baby boy!—and words of doting praise sound richer in German, as Szymborska must have known—goldig or schnuckelig (golden boy, snuggle-puss). So the parents squeeze and primp the baby, dandle and dimple him, chuck him under the chin and smother him with adoring diminutives. Who can resist? The poem is not rigged, as a lesser ironist might have made it, for a slam-bang final stanza ushering in tanks and bombers and concentration camps. Nothing of the sort. It is a snapshot of the infancy of a leader, and there the poem ends. The baby could turn into anyone. His parents were not wrong; none of it had to be and no one is superior to the event:

No one hears howling dogs, or fate’s footsteps.

A history teacher loosens his collar

and yawns over homework.

Another poem of roughly the same family, “Dinosaur Skeleton,” serves as an antidote to the modern self-conceit of landing “on the right side of history” (or in this case, the right side of the evolutionary chain). A guide in a museum of natural history is addressing a mature audience—an audience accorded a status somewhere between docile citizens and the apparatchiks of a one-party state:

Advertisement

Beloved Brethren,

we have before us an example of incorrect proportions.

Behold! The dinosaur’s skeleton looms above—

Dear Friends,

on the left we see the tail trailing into one infinity,

on the right, the neck juts into another—

The poem builds up an extended compliment to the successor creature, humanity itself, by comparison with the sorry endowments of the dinosaur:

Gentle Citizens,

nature does not err, but it loves its little joke:

please note the laughably small head—

Ladies, Gentlemen,

a head this size does not have room for foresight,

and that is why its owner is extinct—

Doubtless the superiority of Homo sapiens was always evident to eyes that could see; our moral greatness can, it seems, be deduced from the aesthetic delicacy of our frame and features:

Distinguished Guests,

we’re in far better shape in this regard,

life is beautiful and the world is ours—

Venerated Delegation,

the starry sky above the thinking reed

and moral law within it—

Most Reverend Deputation,

such success does not come twice

and perhaps beneath this single sun alone—

Inestimable Council,

how deft the hands,

how eloquent the lips,

what a head on these shoulders—

Supremest of Courts,

so much responsibility in place of a vanished tail—

Hamlet’s dignified praise of humanity, “What a piece of work is a man!,” finds an echo in the penultimate stanza—“how deft the hands,/how eloquent the lips”—but the echo is strangely mixed with a memory of his address to the skull of Yorick: “Where be your gibes now? Your gambols?… Quite chopfallen?” The irony here is partly carried by that complex echo, but also by the decision to conclude the poem with a dash instead of a period, which makes the human creature another dinosaur trailing head and tail into infinity. Someday our species may be explained by a tour guide of a different shape.

What do people want? asks Szymborska. The usual answer, it strikes her, is not less than everything. Our appetites are nonnegotiable, a knock at the door that must be answered. Thus “No End of Fun” speaks of a random human specimen:

So he’s got to have happiness,

he’s got to have truth, too,

he’s got to have eternity—

did you ever!

The phrase “did you ever!” turns into the poem’s inevitable refrain.

Can we say that the taste for eternity is any more secure than the taste for beauty? In Symborska’s survey of “Rubens’ Women,” this awareness becomes the motive for exhilarated description:

Titanettes, female fauna,

naked as the rumbling of barrels.

They roost in trampled beds,

asleep, with mouths agape, ready to crow.

Transported by those images, the curator sings out his giddy praise for a dated idiom of beauty:

O pumpkin plump! O pumped-up corpulence

inflated double by disrobing

and tripled by your tumultuous poses!

O fatty dishes of love!

A humorless reverence for art through the ages and the heroes of history may spring from the melancholy of the human creature trapped by the limits of existence. Forever, says Szymborska, is an attempted remedy for the curse of knowing we are here for a while. So the poem “Life While-You-Wait,” with grown-up resignation, declares that “whatever I do/will become forever what I’ve done.”

By contrast, “Interview with a Child” sympathizes with the child’s willful wish not to learn the boundedness of things, the conditions of life that stop every wish from being fulfilled. “How can it be,” Szymborska hears the child wonder, “that whatever exists/can only exist in one way?” And she gives examples: “A fly caught in a fly? A mouse trapped in a mouse?/A dog never let off its latent chain?” All right for them—they are nothing but animals—but it seems an insult to human dignity. “‘No,’ the Master cries, and stomps all the feet/he can muster.”

The aptly titled “Seen from Above” picks an average instance (the case trivial, the consequence null) of the limitations of life that no cry of the will can extend:

A dead beetle lies on the path through the field.

Three pairs of legs folded neatly on its belly.

Instead of death’s confusion, tidiness and order.

But the poet is not moved overmuch: “The grief is quarantined,” she says. “The sky is blue.” Well, but what would our human sufferings look like, seen from above? Szymborska thinks it wrong to suppose any suffering is justified, and equally wrong to imagine we could ever be in a position to pardon ourselves:

On this third planet of the sun,

among the signs of bestiality

a clear conscience is number one.

The rebuke of those lines is underscored by the title of the poem, “In Praise of Feeling Bad About Yourself.”

Her irony never hardens into misanthropy. The reason may lie in a sort of piety one comes to recognize in her work only gradually—a belief, not that we were made by God or made for eternity, but that the world wants to be seen and known; and by whom else should that work be done? In her Nobel Prize speech, Szymborska put the question to the most revered of fatalists:

I sometimes dream of situations that can’t possibly come true. I audaciously imagine, for example, that I get a chance to chat with the Ecclesiastes, the author of that moving lament on the vanity of all human endeavors. I would bow very deeply before him, because he is, after all, one of the greatest poets, for me at least. That done, I would grab his hand. “‘There’s nothing new under the sun’: that’s what you wrote, Ecclesiastes. But you yourself were born new under the sun. And the poem you created is also new under the sun, since no one wrote it down before you. And all your readers are also new under the sun, since those who lived before you couldn’t read your poem. And that cypress that you’re sitting under hasn’t been growing since the dawn of time. It came into being by way of another cypress similar to yours, but not exactly the same.”

A wonderful disquisition and (when you think of it) a motto to explain Szymborska’s work. The title of an early poem says it best: “Nothing Twice.”

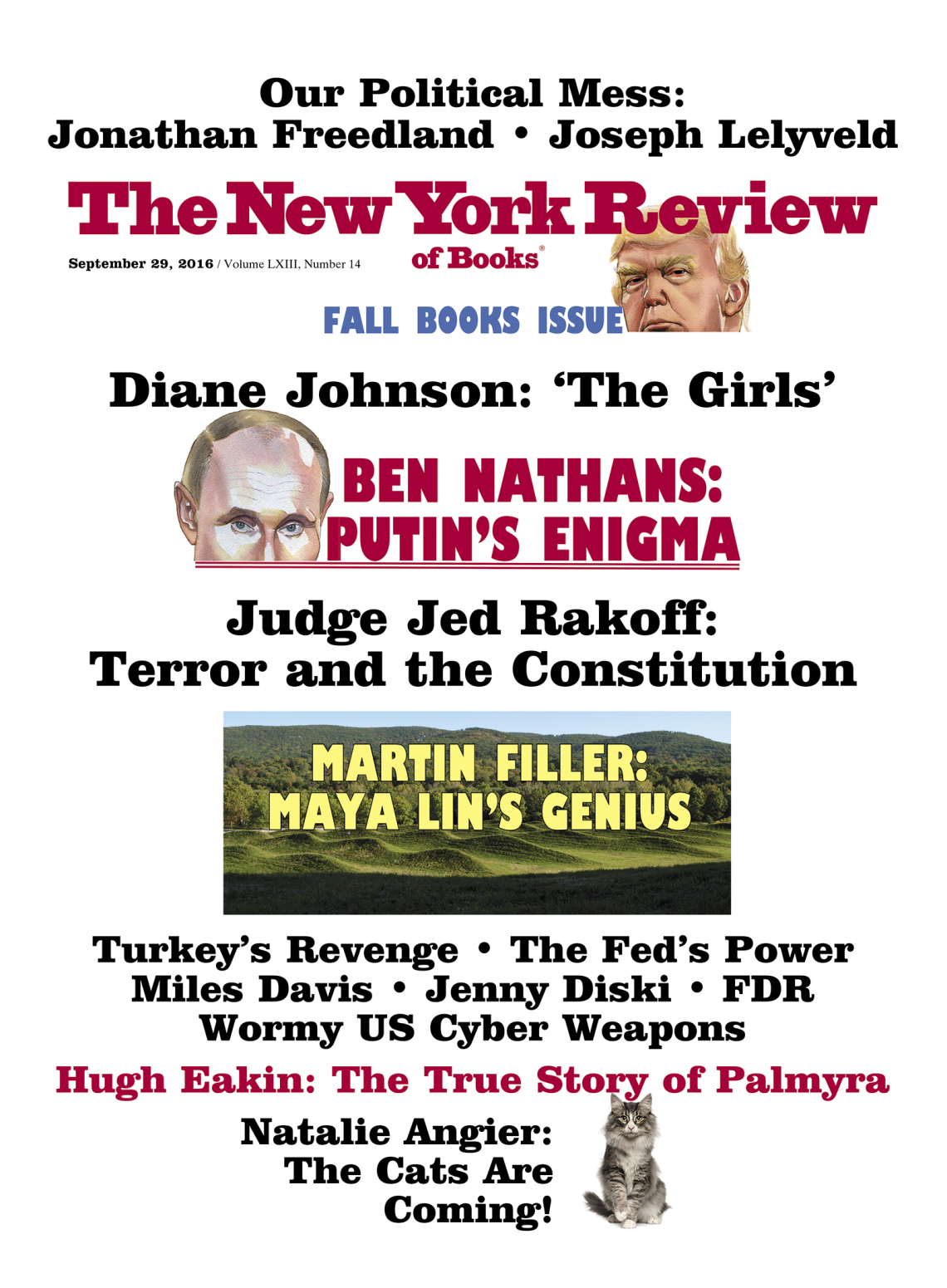

This Issue

September 29, 2016

Maya Lin’s Genius

The Heights of Charm

How They Wrestled with the New