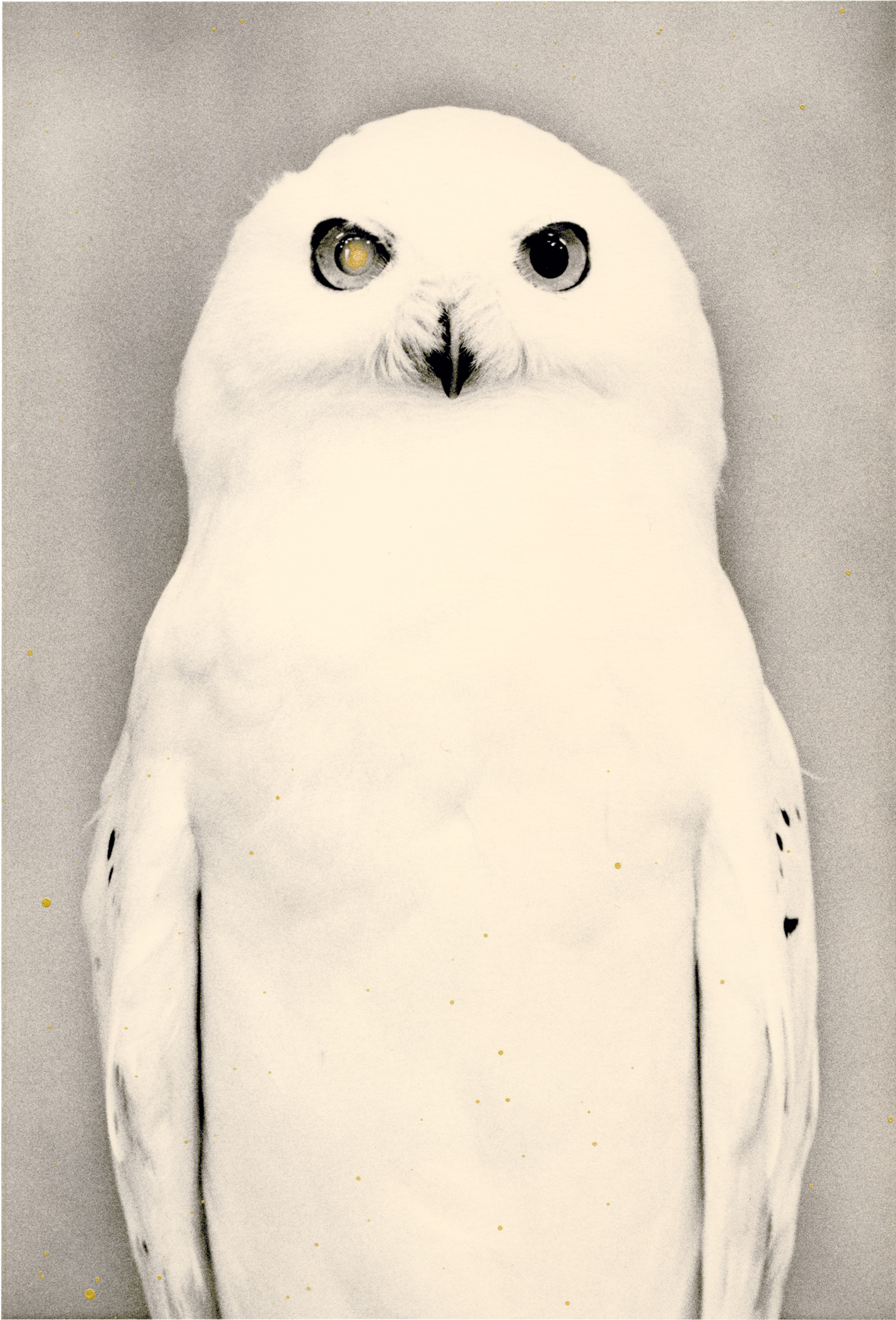

Emmet and Edith Gowin/Pace-MacGill Gallery

Emmet Gowin: Mariposas Nocturnas Index #44, Bolivia, 2011; from ‘Hidden Likeness: Photographer Emmet Gowin at the Morgan,’ a recent exhibition at the Morgan Library and Museum. Gowin’s new book, Mariposas Nocturnas: A Study of Diversity and Beauty, collects fifty-one of his moth grids and will be published by Princeton University Press in September 2017.

Early last May, I sold my old farm and moved about ten miles west. Both places, old and new, belong to what appears to be the same New York landscape: gravel roads, rolling hills, masses of trees—the usual, you might say. But ten miles make more difference than I thought. I live on a glacial drumlin now, not an outcropping of ledge. The soil is heavy with clay, not porous with river rock. There are oaks and ashes and tall black cherry trees instead of beeches and hickories and hemlocks.

Singing in the hedgerows in May were birds I’d never heard before—prairie warblers, for instance, whose song sounds like an upward laddering descant. And fluttering over the fields in June, were those bobolinks? As fall came, I watched a few chimney swifts stuttering and banking in insectivorous flight nearly out of sight overhead.

Most of the birds here are the same ones found at the old farm—the catbird low in the hedgerow, the pileated woodpecker haunting the woods. That is, the species remain the same, but not the individuals. For most of us, a bird’s identity is summed up at the level of species—we see the type as much as the specimen. We clamor endlessly about our own identities and happily attribute individuality to mammals of a certain size—a fox roaming the pasture or a black bear crossing the road at dusk. But the identity of wild birds as individuals is concealed within their identity as members of a species.

I wonder if the concept of “species” doesn’t sometimes get in the way of understanding the effect humans are having on the natural world. After all, a species endures even as the individuals that make it up come and go. But sometimes the word implies that the collective whole—the generality of goldfinches, say—matters more than the individual. Only when a species dwindles to its final numbers do the individuals seem to become, well, individual. Perhaps the only passenger pigeon ever to bear a name was Martha, the very last one.

Finding unfamiliar species at the new farm gave me a momentary sense of avian abundance. But then I remembered that it’s only an illusion.

These thoughts came to me thanks to Michael McCarthy’s powerful, sensitive new book, The Moth Snowstorm: Nature and Joy, a book about the wonders of the natural world and about its decline. In a chapter called “The Great Thinning,” McCarthy, a highly regarded British environmental journalist, notes the difference between extinction at the national level and extinction at the local level. He observes that among birds “there were only two national extinctions in Britain in the post-war period,” the red-backed shrike and the wryneck. “But the number of birds which have declined so much as to be locally extinct, over great swathes of the land, is hugely higher.”

The same is true of wildflowers and butterflies, especially butterflies, which are dear to McCarthy’s heart. In the postwar years, there have been three national extinctions, he writes, “but since the butterfly recording schemes first started, nearly three-quarters of our fifty-eight remaining species have declined and disappeared over much of the country.” In other words, counting the number of species lost doesn’t even begin to reflect the number of individuals lost. Between 1970 and 2013, “the combined population of nineteen farmland bird species” in Great Britain dropped by 56 percent. And since they were declining well before that, “the real figure is obviously much larger; and so with the insects; and so with the flowers.”

The picture is no different in North America. According to a new report from Partners in Flight, a coalition of organizations including the National Audubon Society and the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, forty-six common land-bird species have lost “half or more of their populations—a net loss of 1.5 billion breeding birds” since 1970. (This is to say nothing of waterfowl, shorebirds, seabirds, and rare or threatened species.) Twenty-four of those species have lost between 50 and 90 percent of their 1970 populations. These are astonishing numbers and, like most astonishing numbers, it’s hard to know how to feel their weight. We’ve grown sadly accustomed to the tragedy of the few—to seeing a rare species on the cusp of disappearance, like the black rhino or the lowland gorilla. But this is the tragedy of the common.

As species crash and vanish, the world loses diversity, something it’s been doing for centuries. But the loss of abundance is even more startling. Nature is simply not as full as it once was. Consider the creatures in my own fields. Bobolinks have declined in the US by 74 percent since 1966. Chimney swifts have declined by 72 percent in the same period. As for the solitary monarch butterfly I saw making its way over the goldenrod a couple of weeks ago, that species is declining as well, especially its western population. Something similar has happened to many species: they continue to exist but in greatly diminished numbers, which means that the species itself has a far more tenuous hold on existence. But it also means that the numerical robustness, the plenitude within nature, has dwindled. It’s like looking into the sky and discovering that thunderheads are no longer dark and towering but only faint wisps of themselves.

Advertisement

The Moth Snowstorm is one of the few books I know that tries to grasp how the thinning of nature changes our experience of the natural world. The book takes its name from a visual illusion that has disappeared in England: the way the headlights of a speeding car on a summer night turned moths flying above the roadway into a blizzard of insects. When that happened, McCarthy notes, “the true startling scale of their numbers was suddenly apparent.” People in their fifties and older remember the moth snowstorm vividly, once they’re reminded of it, “as if it were locked away in a corner of their minds.”

The memory of the insect whiteouts seems extraordinary now, but in those days “it just seemed part of the way things were.” This is the trick that time and human nature always play on us. The way things are—no matter how they are—quickly comes to seem normal. It’s as unremarkable not to see moth snowstorms now as it once was to see them. As a species, we too are passing through the bottleneck of the present. It’s stunning to realize that the ampleness of nature in 1970, however you measure it, isn’t even a memory for most Americans. For every generation, nature seems full enough no matter how empty it becomes.

“Even more than the single species,” McCarthy writes, “it’s the loss of abundance itself I mourn.” But it’s a mistake to think of this lost abundance happening only in the past, beyond the memory of youth, as ancient as the plight of the American bison. We are losing it at this moment. McCarthy learned his birding as a boy on the estuary of the Dee, near Birkenhead, England, where he was born. As a result, he has a special fondness for wetland birds, the ones he calls “the gift to us of mud,” whose wildness seems “eternally untameable.”

In 2014 he visited one of the greatest of the world’s estuaries, called Saemangeum in South Korea. Its incredible wealth of birds was first surveyed only in 1998, and it was destroyed—“reclaimed” is the word in development circles—in 2006 when South Korea completed the Saemangeum Seawall Project, which blocked the sea from entering the tidal flats. What McCarthy witnessed in 2014 was a “deadscape.” The completion of the Saemangeum Seawall was “the biggest destruction of an estuary that has ever taken place.”

Yet the death of this major bird-ground is only part of the massive reclamation work going on all around the Yellow Sea, especially in China. Its ancestral mudflats lie at the heart of the East Asia/Australasia Flyway—“older than history, as big as the weather, and something we are only now able to comprehend and visualize.” On that flyway and the Yellow Sea’s rare intertidal zones depend the lives of some fifty million birds, global travelers every one of them. Their habitat is rapidly being engineered out of existence in the name of reclamation, though what is being reclaimed is almost impossible to say. Perhaps the best answer is nationalistic pride. The word itself—“reclaim”—is a misnomer. It is more honest, and more damning, to say that the rich avian habitat of the Saemangeum estuary has now been claimed by humans, the way a miner stakes a claim. Nature will eventually make its counterclaim, but not for many generations to come.

It might have been enough, in The Moth Snowstorm, to survey the destruction of nature in the past half-century—with worse to come, thanks to global warming—and to rail, Lear-like, against it. But McCarthy is stoic in his effort to understand the complexity of how we got where we are and what faces us now. Sometimes the villains are obvious—like overpopulation, industrial farming, and unchecked reclamation—and sometimes they aren’t. There are stories to be told of witless destruction and stories like the one McCarthy tells about the apparent psychological surrender of house sparrows—a once-ubiquitous species that has nearly vanished in London. The sparrows, one scientist thought, “were so strongly social” that they “felt that life in such low numbers was no longer worth living.”

Advertisement

McCarthy wrestles mightily with himself trying to understand who we are and the meaning of “the losses which are making us seem, as a species, like a curse.” Like so many of us, he feels an ambivalence that can’t be resolved. “Sometimes I think there is no light,” he says, “but sometimes I think there is.”

Half of his book contributes movingly to the literature of environmental despair. The problems are too deep and systemic for anything more than the most cautious hope. “There were lots of many things then,” McCarthy says wistfully about his boyhood. And there were lots of many things then because there weren’t so terribly many of us. The natural losses McCarthy chronicles are the result of our going about our business as we’ve defined it since the Industrial Revolution. It seems nearly impossible, for some reason, to make nature count in the minds of humans—count enough, that is, to make mindlessly killing the other organisms on earth even a little harder than it is.

Seeded throughout The Moth Snowstorm is the other half of the book—a study of joy, not loss. McCarthy has set out to write what is, in essence, an environmental theodicy—to account for the existence and purpose of the joy and beauty we feel in the midst of so much loss and despair. “It is clear,” he notes, “that the earth did not have to be beautiful for humans to evolve.” But it is beautiful, and our species has lived in the midst of the planet’s natural beauty for almost the whole of its evolution:

We have been operators of computers for a single generation and workers in neon-lit offices for three or four, but we were farmers for five hundred generations, and before that hunter-gatherers for perhaps fifty thousand or more, living with the natural world as part of it as we evolved, and the legacy cannot be done away with.

McCarthy suggests, as Wordsworth did, that there is an organic correspondence—a radical fittedness—between the human mind and nature itself. “Something dwells already in our minds; and I believe it is the bond, the bond of fifty thousand generations with the natural world, which can make aspects of nature affect us so powerfully.” Love of nature isn’t universal in our species, he admits, but the propensity to love nature is. On this propensity—which flickers in and out of our awareness—rests the whole of McCarthy’s ode to joy.

McCarthy acknowledges that The Moth Snowstorm isn’t really offering an argument. “I am not going to present any evidence for the bond,” he says. Instead, he offers a series of personal epiphanies, moments when he was engulfed by the wonder of nature and found himself uplifted with joy. Again and again writers have tried to do this and failed because they’ve been mainly interested in trying to capture—“express” is always the word—the intensity of their emotions.

But McCarthy has a relatively dry eye, and he trusts his premise. If there’s an evolutionary bond between humans and nature—if the natural world “is as much a part of us as our capacity for language”—then he can lead us into the woods or the wetlands, urge us to look outward, and hope that we’ll find something in our own experience that is proportional to his feelings. To his credit, he never lets his joy in nature overwhelm his descriptions of the natural phenomena that caused it—the snowdrops, the mad March hares, the butterflies clustering on a buddleia, which gave him his originating sense of wonder as a child. McCarthy’s particular skill is to show vividly how intertwined the worlds of the observer and the observed really are.

The trouble comes when McCarthy tries to marshal our joy in nature—our ancient inherited propensity to love it—as a defense of nature. Almost since it began, the environmental movement has tried to perform a kind of psychological jujitsu against human nature—to use our other inborn propensities as a way of tripping up our natural destructiveness. As McCarthy explains, there have been two major strategies for doing this over the past couple of decades. Both are economic. One is sustainable development—the idea that we can go about our usual business while changing its emphasis to include the protection of ecosystems.

More recent—and possibly more powerful—is the “ecosystems services model,” which is an attempt to cost out all the various services that nature provides, as if nature were a giant utility in charge of cleaning the water and freshening the air and sheltering coastlines from damaging storms but incapable of presenting us with a bill we can understand. The point of commodifying nature in this way is to give us a means of putting our actions—destroying mangroves, for instance—in perspective, showing us the hidden costs of what would otherwise look like rational economic behavior. The flaw here is that we can only value the ecosystems services that bear some resemblance to the things we’re used to assessing. Or as McCarthy puts it, “Worth is attributed only to services whose usefulness to us can be directly measured.” But what value, he asks, “do we give to butterflies which, when I was seven, captured my soul? What value do we give, for that matter, to birdsong?”

This is the goal of The Moth Snowstorm, to find “a third way, something different entirely: we should offer up what [nature] means to our spirits; the love of it. We should offer up its joy.” How would this work? What McCarthy proposes is proclaiming the value nature has in our individual lives. Although birdsong can’t be valued in economic terms, we can at least declare that “at this moment and at this place, it was worth everything to me.” We need, he argues, to “proclaim these worths through our own experiences in the coming century of destruction, and proclaim them loudly, as the reason why nature must not go down.” He is proposing a Tiananmen Square protest—the individual against the machine—but without the confrontation: a protest rising from every nature lover in the form of song and celebration.

The vision McCarthy offers is spiritually and emotionally uplifting. He is calling, really, for a heightened state of awareness and the kind of testimony that almost anyone can offer. His proposal is also in keeping with a long history of artistic and philosophical attempts to help us grasp the incomprehensible wonder of the world we live in. He quotes Emerson’s lovely line: “If the stars should appear one night in a thousand years, how would men believe and adore!” And Iris Murdoch’s: “People from a planet without flowers would think we must be mad with joy the whole time to have such things about us.”

But I find “defense through joy” insufficient. Like sustainable development and the commodification inherent in ecosystems services models, it values nature mostly for what it offers us. Ultimately, it’s not radical enough, either as a form of protest or as a philosophical statement. As a species, we repeatedly fail to acknowledge the equal and inherent right of all other species to exist, a right implicit in existence itself and in no way subordinate to our own. We ignore, as if instinctively, nature’s right to itself—its autonomy, if you like. No matter how we feel or act as individuals, what matters when it comes to saving nature is how we feel and act as a species. The news on that score is very grim.

There is one potential practical benefit in McCarthy’s notion of defense through joy. All that testimony—each of us offering our own moments of delight—might turn out to extend human memory of the natural world. It might help keep moments like the moth snowstorms, half a century ago, fresh in our minds, keep them from being so locked away that we doubt our own perceptions. For all our propensity to love nature, we seem to have no collective memory of nature’s fullness—not the fullness of our hunter-gatherer days, not the fullness of 1970, not even the fullness of last year. Nature is only what it is for us here and now. Perhaps if we speak out as McCarthy has done in The Moth Snowstorm—eloquently weaving together the pattern of our lives with the joy, and the crushing, of the natural world—it will be easier to remember how much we’ve lost and how much we have to protect. Perhaps that will make it easier to reclaim nature one day as it should be reclaimed: for nature’s sake.