In a letter of June 1847 to Théophile Thoré, the art critic responsible for the rediscovery of Vermeer, the grandson of Jean-Honoré Fragonard wrote that whenever his grandfather’s work appeared at auction and his name was announced, “Those sympathetic to his art would hear ‘People, pay honour to Fragonard!’ [Gens, Honorez Fragonard!] And the truth of the matter is, that in saying his name out loud, we realized how much he deserved it.”

Fragonard (1732–1806) was a successful, wealthy, and avidly collected artist in his lifetime, who turned his back on the Académie Royale early in his career. By his sixtieth birthday, in 1792, he had retired from painting and drawing altogether to devote himself to the administration of the French Republic’s new museums. Soon forgotten, he was reviled after his death—and well into the middle of the nineteenth century—for his licentious imagery that was seen to incarnate the frivolity of the ancien régime. It was only in the 1860s that Fragonard’s art was spectacularly rehabilitated on both sides of the Channel.

The Louvre received its first (and finest) collection of Fragonards in 1870 with the donation of Doctor Louis La Caze (1798–1869), a pioneer in the treatment of tuberculosis and typhoid fever among the Parisian poor. Second only to that institution, the Wallace Collection in London came to own the greatest concentration of masterpieces by the artist, thanks to Richard Seymour-Conway, Fourth Marquess of Hertford (1800–1870), who acquired his Fragonards for much higher prices in the middle decades of the nineteenth century. Since then Fragonard has never been out of fashion. The American artist Jeff Koons owns a superb example of his erotic painting, and one of Fragonard’s last remaining portraits in private hands was sold at Bonhams auction house in London in December 2013 for over $28 million.

The most exuberant and dynamic artist of the European Enlightenment, Fragonard was an action painter long before the phrase was used. And as we learn from Fragonard: Drawing Triumphant—the excellent recent exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art—he was an action draftsman as well. Fragonard is the joyful chronicler of amorous suitors and happy families. He is the most tender and affecting of religious painters, capable also of searing insights into the power of passion and erotic love. With Jean-Jacques Rousseau, he is the supreme apologist of Nature as a life-affirming force in man’s happiness. Pierre Rosenberg has noted that Fragonard

surpassed all the other artists of his time in depicting not the countryside, but a nature that is both grandiose and inviting, exuberant and overwhelming, familiar and mysterious…. This achievement alone ensures him a place among the greatest masters.

New York is fortunate to have the artist’s masterpiece on permanent view at the Frick Collection. The Fragonard Room there displays The Progress of Love, a series of six large vertical paintings and four overdoors, portraying a pair of youthful lovers in ardent courtship, ecstatic consummation, and contented conjugality. The Frick’s four principal canvases were commissioned in 1771 by Louis XV’s twenty-eight-year-old mistress, the Comtesse du Barry, to decorate a room in her new pavilion at Louveciennes, built at great speed and expense by the architect Claude Nicolas Ledoux. For reasons that are still not entirely clear, du Barry rejected these paintings the following year and returned them to Fragonard without compensating him.

The four canvases remained in his studio in the Louvre for nearly two decades and accompanied him and his family to his hometown of Grasse in January 1790, where they were rehoused in the salon of Fragonard’s cousin and host, the notary Alexandre Maubert. Because Maubert’s salon was larger than du Barry’s, Fragonard needed to add two panels and four overdoors to complete his series. He worked on these additions throughout 1790—as well as decorating the staircase and entrance hall of Maubert’s villa—and these were the last paintings that he made.1

Between February and May 1988, the Metropolitan Museum of Art hosted the most complete retrospective of Fragonard’s art ever undertaken, coorganized with the Grand Palais in Paris, and assembling more than three hundred works—paintings, drawings, and etchings. The six-hundred-page catalog that accompanied that exhibition, written by Pierre Rosenberg with the assistance of Marie-Anne Dupuy-Vachey, is a fundamental scholarly resource and remains the essential publication on the artist.2

One of the great triumphs of that retrospective had been to bring together all seventeen of the exuberantly painted portraits of men and women in Spanish costume, collectively known as the Fantasy Portraits. This series was central to the dramatic reappraisal of Fragonard’s work that occurred four years ago, when an uncataloged and unattributed drawing of sketches after these portraits was recognized as by Fragonard himself, with annotations in his hand.3 Fragonard’s annotations revealed new, and far more obscure, identities for several of the sitters, including two of the most celebrated. The painting in the Louvre long thought to have been of the courtesan and dancer Marie-Madeleine Guimard is now identified as a portrait of the Comtesse Marie-Anne-Éléonore de Grave (1730–1807), from the Burgundian aristocracy, whose youngest son would become Louis XVI’s last minister of war in 1792.

Advertisement

Far more sensational, and reported in both Le Monde and Le Figaro, was the proposal that Fragonard’s Portrait of Diderot in the Louvre represented the minor and forgotten author and publisher Ange-Gabriel Meusnier de Querlon (1702–1780). The most scrupulous art historians had occasionally been troubled by the piercing blue eyes of Fragonard’s sitter, which did not match the chestnut eyes in Louis Michel Van Loo’s commissioned portrait of Diderot, shown at the Salon of 1767. But to demote from canonical status this swashbuckling effigy, with voluminous starched collar and golden chain—the cover of the Oxford World’s Classics Jacques the Fatalist—had hitherto been unthinkable.

Several inches shorter than Picasso—just under five feet tall—in his later years, Fragonard was described as “round of face, high-spirited, always active, always cheerful, with fine rosy cheeks, twinkling eyes, and disheveled gray hair.” Apparently, he was “extraordinarily plump” at the time of his death on August 22, 1806, when he and his wife were tenants of the restaurateur Véry in the Palais-Royal (in a building that now houses Le Grand Véfour).

Born in 1732 in Grasse, Fragonard was the only child of a glove maker and his wife who moved to Paris in the late 1730s and lost their fortune in an ill-advised speculation. After serving a brief apprenticeship as a notary’s clerk, Fragonard entered Chardin’s studio, before being accepted by François Boucher, whom he assisted on cartoons for Gobelins and Beauvais tapestries.

Although he had not formally enrolled as a student of the Académie Royale, under Boucher’s supervision Fragonard received the training of a history painter, and became adept in composing multifigured religious, mythological, and classical subjects, at the summit of the Academy’s hierarchy of the genres. A star pupil, Fragonard won the prestigious Prix de Rome on his first attempt in August 1752. Before leaving for Rome as a pensionnaire of the Crown, he entered the recently established École des Élèves Protégés, a finishing school for laureates under the directorship of Carle van Loo, where aspiring history painters, sculptors, and architects received four years of additional training in the practical, theoretical, and literary foundations of their craft.

Finally, in December 1756, the twenty-four-year-old Fragonard arrived at the French Academy in Rome, housed in the Palazzo Mancini on the Corso. Like his teacher Boucher before him, Fragonard seems initially to have been afflicted by an early strain of what became known as the Stendhal Syndrome. He later recalled that he was almost paralyzed by the art and antiquities that confronted him, scarcely able to hold his crayon, and unable to work. Thanks to the encouragement of Charles Joseph Natoire, director of the French Academy in Rome, and the support and patience of the authorities in Paris, Fragonard overcame this initial setback, settled happily into the exercises expected of pensionnaire history painters, and immersed himself in the city and the surrounding countryside.

Like his friend Hubert Robert, he benefited from the patronage of the generous and enlightened amateur (and amateur engraver), Jean Claude Richard, abbé de Saint-Non, conseiller clerc au Parlement de Paris (1727–1791). In the summer of 1760, Saint-Non invited Fragonard to join him at the Villa d’Este in Tivoli, where the artist’s red chalk drawings translated his experience of nature more vividly and more directly than had heretofore been approved of by artistic theory or academic practice. Saint-Non also accompanied Fragonard on his return home to Paris. Between April and September 1761 the two men visited practically every town of interest in Northern Italy, with Fragonard making over four hundred black chalk copies of the old master paintings that they saw.4

Back in Paris, Fragonard spent almost three years preparing his admission piece (morceau d’agrément), required to gain associate membership in the Académie Royale and which also permitted the junior members to exhibit at the Salon. He chose an obscure tale from the seventh book of Pausanias’s Description of Greece: the episode when Coresus, a Calydonian priest in Dionsyus’s service ordered to sacrifice the maiden Callirhoë (with whom he is in love), instead plunges the dagger into his own breast. An enormous canvas, ten feet high, thirteen feet long, Coresus and Callirhoë was not a commissioned work, yet it is clear that Fragonard was painting it for the Crown, even though he had no assurances that it would be acquired by the Maison du Roi.

Advertisement

Acclaimed by both fellow Academicians and art critics, this ambitious history painting was indeed purchased by the royal administration to be woven as a tapestry by the Gobelins. Fragonard was offered a studio in the Louvre, and commissioned to produce a companion picture also to be woven as tapestry. Three and a half years of preparation had paid off. The young artist had secured for himself a place in the stable of emerging neo-Baroque history painters who could be called upon to provide decorations for the palace of Versailles and other royal residences.

Fragonard’s career as an official Crown artist now seemed assured. Indeed, for his reception piece (morceau de réception), commissioned in July 1766, he was assigned one of the empty ceiling compartments in the Galerie d’Apollon in the Louvre, left unfinished at the time of Charles Lebrun’s death in 1690. A canvas much larger than Coresus and Callirhoë, Fragonard’s ceiling was to represent an Allegory of Spring. Despite numerous official reminders, he did not produce the pendant to Coresus and Callirhoë nor did he ever begin work on his ceiling for the Louvre. However, he never relinquished his lodgings in the Louvre and kept the apartment in the Cour Carrée, given to him in 1765, until 1788. In 1792, thanks to Jacques-Louis David’s support, he and his family moved into even more commodious quarters in a different part of the palace: a suite of eight rooms on three floors, with its own wine cellar.

In the late 1760s, decorative commissions began to pour in as well from private clients such as the Marquis d’Argenson, the courtesan and dancer Guimard, and the maîtresse en titre du Barry, each represented by their architects. Like the royal administration, such patrons might be less concerned with the timely acquittal of payment. The novelist and chronicler Louis-Sébastien Mercier recalled that Fragonard was so poor at this time that he had to pawn his clothes and was reduced to painting portraits “à un Louis.”

Recently married and with a daughter, Rosalie, born in December 1769, the artist turned increasingly for his livelihood to the burgeoning Parisian market for contemporary art. He responded both to the now fairly well-established demand for relatively small paintings by living artists—known as cabinet pictures—as well as to the new fashion for collecting independent, autonomous drawings by them: drawings in mats and mounts, framed and glazed, that were also traded on the secondary market.

Fragonard thus bypassed the Academy, chose not to participate in the Salon after 1767, and was criticized for his “avidity.” Louis Petit de Bachaumont, author of the widely read Mémoires secrets, claimed in 1769 that “love of money” had “derailed Fragonard from the fine career upon which he had embarked,” and that the artist was “now content to excel in boudoirs and dressing rooms.” At the auction of his master Boucher’s collection in February 1771, Fragonard purchased more than five hundred items in sixteen lots, at a cost of just under 1,600 livres.

The year 1772, however, was something of an annus horribilis for Fragonard. His paintings for du Barry at Louveciennes were taken down and returned to him; the ceiling he had painted in 1767 for the Marquise d’Argenson’s dining room was replaced; a commission to decorate Guimard’s salon foundered on Fragonard’s financial demands. (He had estimated the work at 6,000 livres, but later determined that he would need 20,000 livres and four years to complete the project.) To resolve this crisis, perhaps, another long-standing patron, the immensely wealthy financier Pierre Onésyme Bergeret de Grandcourt (1715–1785), invited Fragonard and his wife to join him and his entourage on a year-long visit to Italy, where Fragonard would serve as traveling companion and cicerone. Patron and painter had recently traveled together through Flanders and into Germany in the summer of 1773, and the group embarked on their Grand Tour in early October.5

Fragonard’s second visit to Italy, as a mature artist, was a year devoted entirely to drawing. Working in all graphic media, he created a series of extraordinarily accomplished portraits, landscapes, and genre scenes, as well as superb copies of old masters (far fewer in number than those made on his first visit a decade earlier, but more monumental). In particular his wash drawings—in which ink was diluted with water—achieved a fluency and humanity that testify to his absolute command of this exacting medium. Unlike painting in oil on canvas, inks diluted in water and applied by the brush cannot be corrected or reworked on the sheet.

Bergeret kept a meticulous diary of his travels, in which Fragonard—“mon camarade de voyage”—is mentioned only occasionally. It is clear from his Journal that Bergeret considered Fragonard’s drawings to belong to him.6 This was in line with seigniorial precedent whereby the production of an artist sponsored by a patron became de facto the property of the patron. Having prevailed upon the Elector of Saxony to open his picture gallery in Dresden for them in August 1774, Bergeret noted that Fragonard and his wife were hard at work by eight in the morning. He returned to the galleries in his carriage later in the day to “harvest their drawings” and transport them back to his lodgings.

It will come as no surprise that this trip ended poorly for Fragonard and his wife, when they realized that Bergeret intended to keep possession of the drawings. Following the debacle with du Barry, the unhappy conclusion of this Grand Tour meant that Fragonard’s livelihood would have been compromised for two years in a row. The artist took his patron to court, sued for the return of the drawings (or payment of 30,000 livres for them), and seems to have prevailed, since it is likely that most of the drawings were indeed restored to him.7 The judicial records for this case have never been recovered, but the episode confirms Fragonard’s independence and his status as a “professional artist”—to use a somewhat anachronistic term. “Of all our artists,” noted Mercier, “Fragonard is the one who lives most for his art and for himself, without ambition. He does not waste his time paying court, receiving visitors, or dining out en ville.”

Fragonard’s modern sensibility is also evident in his drawing, the subject of the exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and its handsome catalog. Remarkably, this survey of seventy-seven drawings and twenty-three etchings, covering every decade of the artist’s career, and with fine examples of nearly every genre and in every medium, was composed entirely of works from New York, with forty-seven drawings borrowed from private collections in the city. Installed chronologically, the exhibition and catalog strove to refine our understanding of Fragonard’s complex stylistic development and to identify more accurately the subjects of his drawings. The curators’ exacting connoisseurship in assigning a date (or range of dates) to each work, and the discrimination with which they deconstruct what is represented on each sheet, aspire to “a narrowing of uncertainty.” Such efforts are essential in any appraisal—or reappraisal—of Fragonard’s art. As Perrin Stein notes, “Undated, works are untethered from their social context, and meaning ebbs away.” Fragonard’s capacity to work in different modes at the same time presented an additional challenge.

Yet from the restricted pool of drawings and prints at their disposal, the organizers of this exhibition showed very fine—and in some cases, surpassing—examples of every category of Fragonard’s graphic production (with the exception of his religious drawing). The first gallery displayed early academic red chalk studies, black chalk copies after the old masters, Italianate landscapes, Dutch-inspired pastorals in chalk and wash, and a wall of imposing history subjects from classical mythology and Renaissance literature. The second room showed Fragonard’s work between 1770 and 1775, with a very strong selection of red chalk and wash drawings from the second trip to Italy. The final gallery was devoted to Fragonard’s allegories, genre subjects, and landscapes of the late 1770s and 1780s, and his illustrations of Ariosto’s Orlando Furioso (which he may have read in the original) and La Fontaine’s Contes (which he surely knew by heart).8

It is immediately apparent from this exhibition that Fragonard avoided one of drawing’s primary traditional functions: there are scarcely any preparatory studies for his paintings, and even fewer preliminary sketches for them. While we can be sure that Fragonard drew constantly in sketchbooks that he kept in the pocket of his coat, only one such book survives intact in the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam.9 Yet this sort of sketching had a vital function, as Eunice Williams notes in the Met’s catalog: “If Fragonard’s composing seems effortless, it is because he had observed nature closely and made casual black chalk sketches in notebooks now dispersed.”

The authors stress—at times a little too much so—that for Fragonard drawing was not subordinate to painting, nor was it a subsidiary component of his creative process. His working method is described (without irony) as “nonlinear” and “nonhierarchical.” Indeed it is the case that Fragonard made drawings in preparation for other more ambitious drawings, and three pairings in the exhibition documented this way of working: the sketch in wash with touches of gouache for the more expansive wash and watercolor of Landscape with Stormy Sky; the red chalk study and finished drawing of A Gathering at Wood’s Edge; and the animated sketch and equally animated final drawing of The Bread Oven at the Château de Nègrepelisse. As the catalog makes clear, some of Fragonard’s spirited and autonomous compositional drawings might record paintings after their completion or embody ideas for paintings yet to be executed. There are even instances of fully worked compositions in pen, ink, and wash tackling a subject with greater amplitude and ambition than would be invested in its painted version.

Fragonard’s manner of drawing was idiosyncratic in the extreme. As Eunice Williams first noted almost forty years ago, his preferred method was to block out the vaguest of compositional outlines in faint black chalk or graphite underdrawing that appears as nothing more than a skein of scribbles, often illegible to the naked eye. This speedily sketched black chalk armature—used even for some of his red chalk drawings—seems to have been essential in inspiring both his mind and his hand. Details would then be worked out in softer black or red chalks, and with washes of different tones applied with the brush in several applications. Even in wash drawings that replicate a composition, stroke for stroke, Fragonard initiates the process with such black chalk underdrawing that allows him to reinvent his motifs de novo.

Fragonard also made more than one version of some of his autonomous drawings, no doubt in response to market demands, but without ever simply copying the original. A suite of five examples in different media of The Little Park, some of the most atmospheric sheets in the exhibition, documented this iterative process. The touch, or “aura,” of the original is present in each of these works, distinguished by subtle gradations in luminosity and lushness. Leafy trees and overgrown bushes weigh heavily in one composition; light bursts brightly through the bower in another; falling branches and ruined tree trunks communicate a sense of neglect and decrepitude in a third.

In whatever medium he chose, and in whatever genre he worked, Fragonard imparted to his drawings, as to his paintings, a sense of motion, energy, and sprezzatura only made possible by his sustained engagement with the art of the past and his keen and constant observation of the world around him. The spontaneity of his draftsmanship is highly mediated; brio and effortlessness are willful, managed effects. Fragonard seems to have taken to heart the good advice conveyed to him by Natoire during his student years in Rome: “A painter must not forget color and effect, even when drawing.”

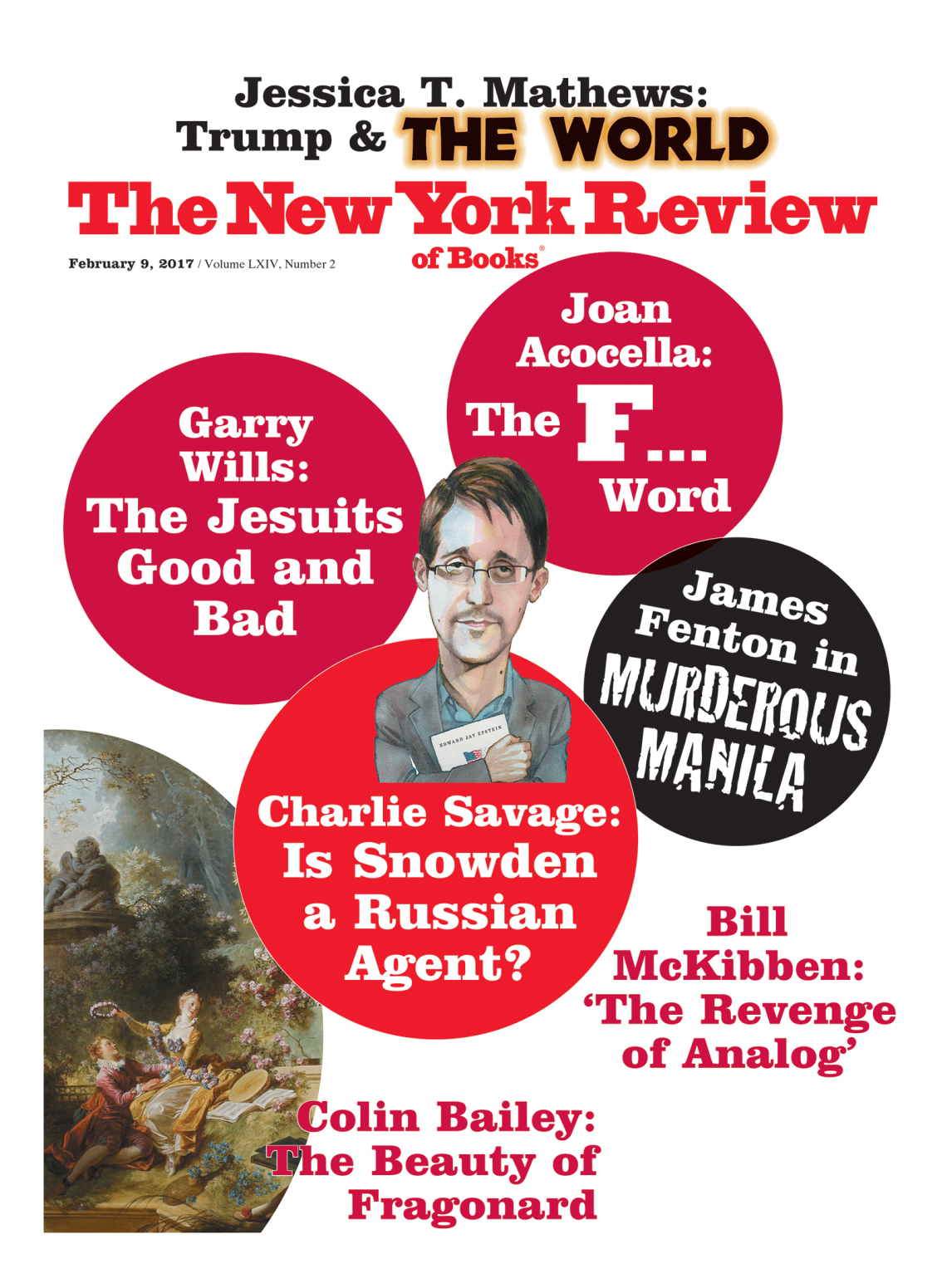

This Issue

February 9, 2017

Was Snowden a Russian Agent?

The F Word

Trump & the World

-

1

See Colin B. Bailey, Fragonard’s Progress of Love at the Frick Collection (Giles, 2011). ↩

-

2

Pierre Rosenberg, Fragonard (Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1988). The exhibition was shown at the Galeries nationales du Grand Palais in Paris between September 1987 and January 1988. Marie-Anne Dupuy-Vachey is currently preparing the catalogue raisonné of Fragonard’s drawings. ↩

-

3

The anonymous drawing appeared for sale in Paris’s Hôtel Drouot on June 1, 2012, and was first published by Dupuy-Vachey, “Fragonard and the Fantasy Figure: Painting the Imagination,” The Tribune de l’art, July 20, 2012. For the proposed new identities of the sitters, see Carole Blumenfeld, Une Facétie de Fragonard: Les révélations d’un dessin retrouvé (Montreuil: Gourcuff Gradenigo, 2013). ↩

-

4

Three hundred sixty of these drawings are reproduced and cataloged in Pierre Rosenberg and Barbara Brejon de Lavergnée, Saint-Non, Fragonard; Panopticon Italiano: Un diario di viaggio ritrovato, 1759–1761 (Rome: dell’Elefante, 2000). ↩

-

5

The exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art includes a spirited drawing that is now dated to late August 1773 and shows Bergeret and his traveling companions in their well-appointed cabin, en route to Düsseldorf, suffering from seasickness during a rough Rhine crossing. ↩

-

6

Bergeret’s diary was published by Albert Tornézy, Bergeret et Fragonard: Journal inédit d’un voyage en Italie, 1773–1774 (Paris: May et Motteroz, 1895). Bergeret’s impassioned (and damning) reappraisal of Fragonard and his wife—“des gens faux”—likely made after Fragonard brought suit against him, can be seen in his marginal revisions to the first page of his Journal, reproduced in Rosenberg, Fragonard, p. 370. ↩

-

7

It should be noted that the meticulous pen-and-ink inscriptions on several of Fragonard’s Italian drawings done in 1773 are in Fragonard’s hand. Bergeret’s writing is wayward and undisciplined. See the examples of his looping handwriting illustrated in Sophie Raux, “Le voyage de Fragonard et Bergeret en Flandre et Hollande durant l’été 1773,” Revue de l’Art, No. 156 (2007), pp. 11–28. This has nothing in common with the finely penned inscriptions on sheets such as Portrait of a Neapolitan Woman from the Thaw Collection at the Morgan Library and Museum; see Stein, Fragonard: Drawing Triumphant, pp. 188–189. The attribution of these inscriptions to Fragonard was first made by Eunice Williams, Drawings by Fragonard in North American Collections (National Gallery of Art, 1978), p. 94. ↩

-

8

Fragonard’s literary illustrations give the lie to Rosenberg’s surely half-serious assertion that the artist was illiterate; see Rosenberg, Fragonard, p. 15. ↩

-

9

The remnant of a second sketch book is at the Fogg Art Museum and contains thirty sheets with forty-five sketches, see Williams, Drawings by Fragonard in North American Collections, pp. 56–58. ↩