For a number of artists, writers, museum curators, and others concerned with the way we think about contemporary art, few exhibitions have been as anticipated as the current Francis Picabia retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art. In recent decades, not many historical figures have seemed as ripe not only for reevaluation but simply to have her or his work seen fully.

When the French artist died, in 1953, at seventy-four, and in the years that followed, Picabia was thought of (when he was thought of at all) as a figure of the past. He had been a leading light of Dada—that irreverent, short-lived, and happily uncoordinated movement that grew directly out of fury over the meaningless slaughter and destructiveness of World War I. Through writings (often nonsense writings), artworks (often created with parts put in place by chance), and the way one behaved in public (wild parties were the order of the day), Dada was about undermining, disrupting, or at least satirizing the traditions and proprieties, and the sheepish adherence to them, that presumably helped bring on the war in the first place.

Picabia’s chief contributions to the Dada spirit were drawings and paintings of machines, or elements in engines, which stood in part, in Dada’s upside-down thinking, as new ways of looking at people. But after the movement’s demise in the mid-1920s, Picabia continued to make art, and it was these later works that, beginning to be seen more widely during the 1970s, mostly in Europe, called out for attention. They included abstractions, but most were representational images and it wasn’t clear how they were all by the same artist. Some were of overlapping images, or multiple exposures, and seemed to presage by decades what, in the end of the 1970s and the beginning of the 1980s, Sigmar Polke and David Salle, among others, were doing.

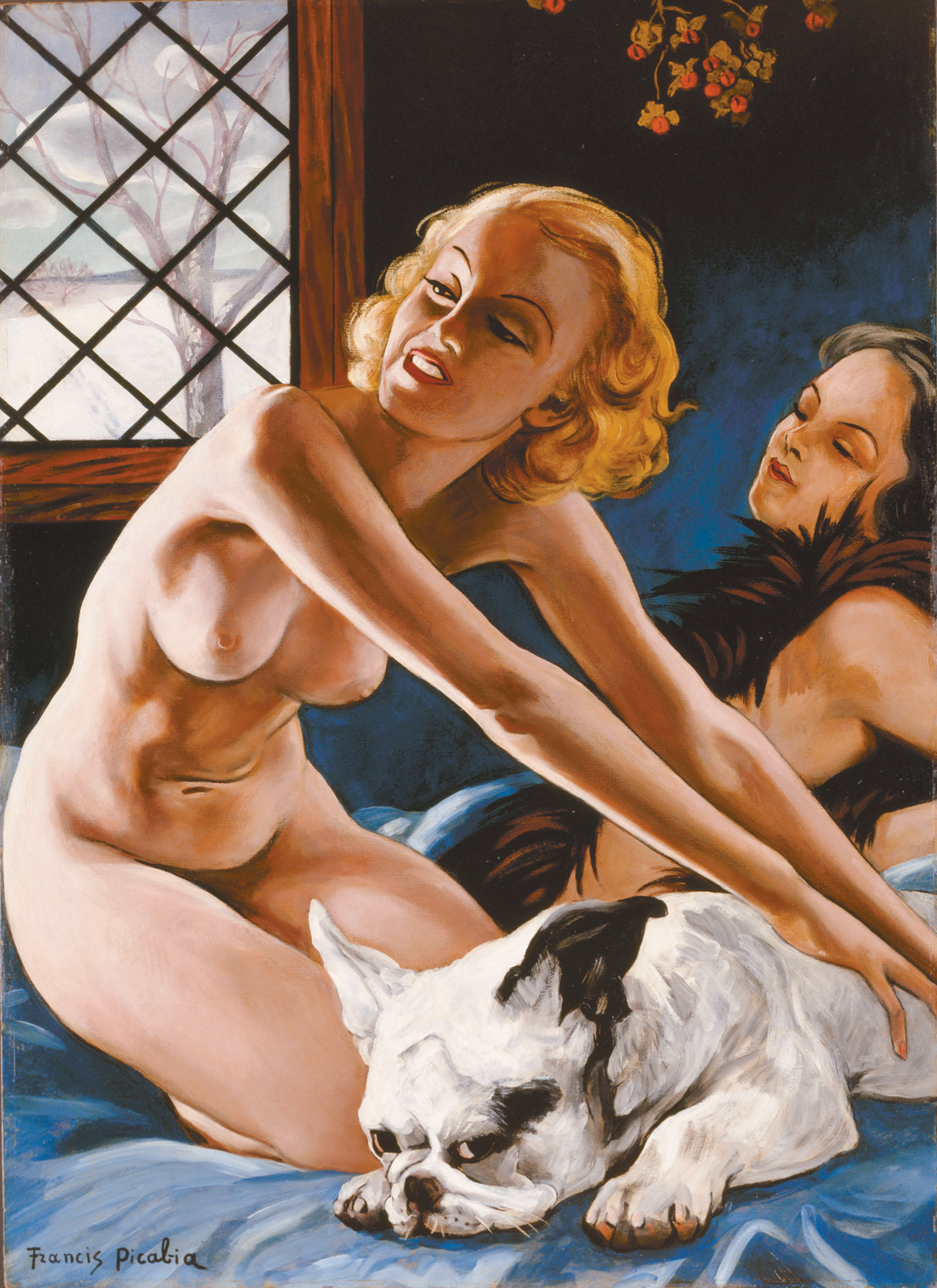

Others were like painted versions of covers of trashy romance paperbacks or stills from B-movie melodramas. They started appearing at a propitious moment. In the later 1970s, the hold that Minimalism and Conceptual Art had long maintained on contemporary art was beginning to seem untenable. The theoretical positions taken against painting as an art form and against human representational imagery, which pervaded the art magazines and art-school teaching of the era, were being questioned, and the later Picabia, it appeared, had barreled through the orthodoxies of the modern movement in ways that seemed like a gift to a future generation.

Much of the impetus for looking at Picabia’s forgotten pictures came, in fact, from artists. As Peter Fischli puts it in an interview about Picabia in the Modern’s catalog—Fischli and his then partner, the late David Weiss, had helped organize a sizable Picabia show, in 2002, at the Musée d’Art moderne de la Ville de Paris—Picabia was a “pre-postmodern.” David Salle is also interviewed in the Modern’s catalog, and he has gone further into the subject in “Picabia, C’est Moi,” an essay that appears in How to See, his new collection of art writing.1

In it, he catches the exact reason that Picabia’s later art was finding an appreciative new audience. “I had never before seen painting,” Salle writes, “as untethered to notions of taste or intention; there was no way of knowing how to take it, or whether even to take it seriously at all. The work was so undefended—it was exhilarating.”

With the Modern’s large show, the first in this country to bring together in a thorough manner nearly every aspect of Picabia’s work—and to celebrate in its catalog these aspects—the artist is no longer precisely an undefended figure. He is, though, a complex one. The exhibition, which was earlier shown at the Kunsthaus Zürich—and reviewed with a different emphasis than my own by Alfred Brendel in this magazine2—gives us, in effect, two hazily known artists. There is the later Picabia who made the groups of idiosyncratic pictures that have intrigued and mystified viewers in recent years. And there is the earlier Picabia—whose work has not been seen in depth in New York since 1970—who began as an Impressionist, moved on to a Cubism of sorts, and hit his stride in the late 1910s as a Dada artist and a busy contributor to the movement’s events. They included a ballet he fashioned with Erik Satie and, showing regularly in the current exhibition, a short movie (having to do with a runaway hearse) put together with the young René Clair.

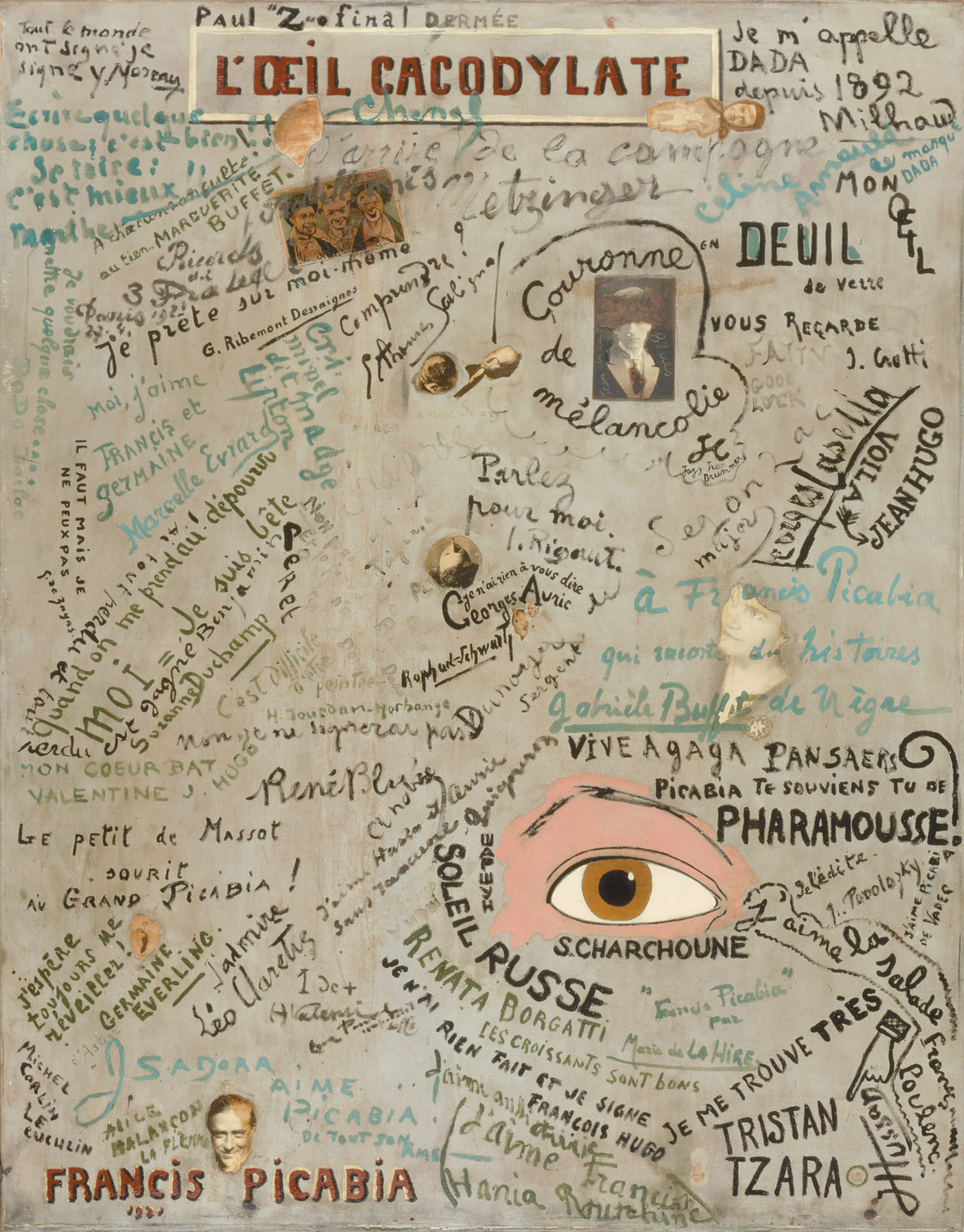

There are strong, or pleasing, works on view from a number of these (and still other) phases, and one of them, L’Œil cacodylate (The Cacodylic Eye), from 1921, is a singular picture that freshly encapsulates an era in European life. It is a kind of collage, and has little overt relation to the pictures of Picabia’s that we are most interested in seeing now, but for this viewer it is a marvelous find. Picabia’s works from the early 1940s, moreover, which are very much among those pictures that have been gaining currency, create a grim and off-kilter mood that is hard to describe or dispel. It blends the erotic, the conventionally romantic, and the political.

Advertisement

Yet Picabia doesn’t come across as a neglected giant. The exhibition presents too many emotionally thin, quickly digestible works. That may be partly what he wanted; and as Anne Umland, one of the show’s curators, writes in her introduction to the catalog, it is Picabia’s “irrepressible, unruly, nonconformist genius”—his “desire to be consistently inconsistent”—that counts. It offers “a powerful alternative model.” This is understandable, but it doesn’t make the paintings or drawings more satisfying. Although Umland doesn’t quite come to this conclusion, one can believe that Picabia largely always operated as a Dada artist and that for him artworks by nature needed to be some combination of taunts and wake-up calls.

For visual artists, the Dada spirit meant in good measure stripping the foremost traditional art form, which was painting, of its importance. Painting, it may even have been felt, mirrored the thinking of the generals and politicians who led the world to a pointless war. Painting was an art form bound up in its own specialness, its own house rules, which had no room for messy real life. Marcel Duchamp took the tenor of the time to its logical conclusions in first giving up painting and then rarely making art of any kind. It wasn’t coincidental that some of the foremost artworks associated with Dada were collages (by Kurt Schwitters, Max Ernst, and Hannah Höch, among others), not paintings, and that the materials used for collages were often ripped papers and stubs bound for the wastepaper basket or old engravings cut out of books.

Picabia remained a painter, but surely some of the gambits he took with oils on canvas, and some of the unconvincingness that attends many of them, derive from his wanting to undermine the art of painting and the art world that protected it. He may have been thinking about confounding his art audience from his earliest days. It can be sensed in his Impressionist landscapes, the first pictures we encounter at the show. They were done before Dada existed. Yet, created around 1905 to 1909, or some thirty years after Impressionism was a new and vibrant movement, they have about them a jab aimed at the art world’s belief that art styles lead progressively from one to the next. Picabia might have been saying with his (rather vapid) landscapes, “Can’t art go backward?”

He was an ironist and a contrarian by temperament. In an era when writers and artists saw received opinions and all proprieties as so much sham, his contribution was the thought that diversions were what mattered. Independently wealthy, chubby, possessed of a wad of lustrous, dark hair (he was Spanish and of aristocratic descent on his father’s side), Picabia was known for his appreciation of showgirls, racing cars, and life with the party set. After he moved to the Riviera, in the mid-1920s, his appreciations also included gambling and yachting. (In snapshots of the era, he often has a tan.) When he wasn’t acting as a playboy, though—he supplemented his income in the 1930s by being an organizer of fetes and soirees—much of his energy went into producing and designing pamphlets and little magazines. He was often dashing off poems and aphorisms, and he wrote a novel but was unable to get it published.

The Modern has chosen one of his epigrams, “Our heads are round so our thoughts can change direction,” for the subtitle of its exhibition, and uses others, including “Every conviction is an illness,” to advertise it. Picabia’s words show him to have been as much an agent of disillusionment as he was a cultivator of frivolity. Sometimes, though, his words are no more than ordinary quips, and there being no selection of his writings in the catalog one assumes that in general they are slight. How assured and magnetic he could be as a person comes out in an Alfred Stieglitz photograph of him from 1915, in which he wears a bowtie and leans toward us, a slight smile on his face. (It is not reproduced in the catalog.) Picabia was often in New York between 1913 and 1917, and here Stieglitz, a good friend, caught a figure of considerable sensuous handsomeness. He looks like what might be called a Mediterranean banker prince.

Advertisement

Picabia’s textbook reputation has long been based on his machine pictures. They are images of rotaries and pistons, cameras, spark plugs, and so forth, taken from science magazines and ads and then sometimes altered. Very often they include the name of the person they evoke or words of ambiguous import. The majority are works on paper and present these precisely detailed items in lean, outline form.

A few of them, I think, are all a viewer will want to see. They feel like a tricky, abstruse version of Cubism. When Picabia made them as paintings, however, using larger sizes, brushing in color, and adding more little words to the images, he created works, as in the Modern’s own M’Amenez-y (Bring Me There), of 1919–1920, that are like official announcements that have been charmingly toyed with by a smart street artist.

The best aspect of the pictures may be Picabia’s subtly awkward hand lettering, which is like a door that lets us get into the impersonal machine world he presents. He used it with varying degrees of wobbliness in many pictures, maybe in none so effectively as Portrait of Cézanne, possibly his most reproduced piece. Now known only in a photograph, this 1920 work features a toy monkey that has been affixed to a board. Above it we read “Portrait de Cézanne,” and on the monkey’s other sides we find “Portrait de Rembrandt,” “Portrait de Renoir,” and “Natures Mortes,” all lettered in a hand that suggests a child trying to be very neat. (If Dada had a mascot it would probably be this monkey.)

It might have been the fun of doing the lettering in his Cézanne portrait that led Picabia the following year to L’Œil cacodylate, a picture that is in good part about handwriting. The story is that the artist had an eye infection and his doctor told him to stay home and use cacodylic eyedrops. Perhaps to amuse himself, he put up a five-foot-high canvas on his easel and had his friends come by and sign it. The picture was complete, he wrote (perhaps with a Dada disdain of the art of painting), when there was no room left for more signatures. When he said in the same article that he found the work “very beautiful,” and added, “it is perhaps that all of my friends are artists just a bit,” he might also have been speaking in the language of Dada, which set out to dislodge the notions of the unique masterpiece made by the uniquely skilled master.

L’Œil is on one level simply an informal testament to the vibrancy of Paris at the time (and to the range of Picabia’s friendships). Marcel Duchamp and Jean Cocteau are listed in the catalog as being among the forty-odd signatories, though I have not yet found Duchamp’s signature or Man Ray’s, who apparently added “directeur du mauvais movies.” But “Ricords di 3 Fratellini,” the Italian circus performers, can be made out, and the American silent movie comedian Fatty Arbuckle adds after his name “GOOD LUCK.” Isadora Duncan, who contributed “ISADORA AiME PiCABiA! DE TOUT SON ÂME,” is unmissable, as are three composers, all wits: “Je m’appelle DADA depuis 1892,” writes Darius Milhaud. Georges Auric is not playing along: “je n’ai rien a vous dire,” he says, while Francis Poulenc, who perhaps signed the picture at a later time when it was in a public place, helpfully notes “J’aime la salade.”

Picabia went on to show L’Œil at the Salon d’Automne in 1921, where it must have been seen as a display of Dada impudence. Picabia, after all, did not make it. He was more like the work’s maître d’. The word cacodylic, in addition, comes from the Greek for “foul-smelling,” and the very idea of a foul-smelling eye—Picabia has painted a large eye toward the bottom, which anchors the many signatures—has a Dada ring to it. Yet Picabia was right to call it “beautiful.” It is a work of formal strength and delicacy.

With its swaying eddies of letters and words, and the curving linear flourishes that various signers could not resist adding, L’Œil forms a kind of latticework web. (It forms a preview, too, of the remarkable paintings with words written here and there in script that Joan Miró would make a few years later.) Its color is nuanced. Against its smudgy gray background, the signatures are in black and pale green, and Picabia has put his title at the top of the canvas and his name at the bottom (along with a photo of himself) in dark red capital letters. The snapshots and clippings that have been pasted on sparingly add flecks of white and tan, and the big, foul-smelling eye is surrounded by a swath of pink.

L’Œil was perhaps inadvertently a marker for Picabia. It turned out to be a farewell of sorts to the Dada group, which he formally left in 1921. Within a few years he was living in the South of France and had embarked on the first of his many different kinds of representational paintings. He would be involved with them for the next twenty years, or through World War II.

When the war was over he returned to Paris and, now approaching his late sixties, became a painter of abstractions, many having to do with the placement of dots or circles. Some of these paintings, which bring the Modern’s retrospective to its conclusion, are sweet enough. In the slightly tentative way that they have been painted, Picabia’s dots and circles are like a continuation of the way, in earlier days, he adorned his pictures with lettering.

It is the representational pictures, though, that hold our attention—even when they are dismayingly odd, or plain terrible. Dating from roughly 1924 to 1944, they comprise a show within the show. And yes, as one had suspected from seeing this or that Picabia in a gallery or magazine over the past years, the artist had no lasting loyalty to any style or approach. From one group of pictures to the next we could be looking at a different painter.

Picabia’s earliest group, referred to as “Monsters,” has a lively and original formal presence. In these costume-partyish scenes of embracing and kissing couples and single figures, arms, hands, torsos, faces, and eyes all seem to be made out of confetti and thin, cardboard-stiff, ill-fitting, pasted-on parts. The odd achievement of the pictures is that nothing in them seems anchored. One feels that if the paintings were jiggled the eyes, the eyelashes, and everything else we see would fall easily to the bottom.

Later in the 1920s Picabia went on to make more ambitious pictures with disembodied figures. This time his figures—and animals and trees and leaves—all appear to be floating through one another. Known as “Transparencies,” these are the paintings that some viewers may think of when the subject is Picabia’s buried later work or how he was a precursor to, say, Sigmar Polke.

Based on the examples in the exhibition, however, the Transparencies, which, in their imagery, take us into an ethereal, biblical-classical netherworld, cannot be compared to the work of Polke or David Salle. They are not in the same league. They are dingy, brownish paintings, dead from inception because they are based principally on the single black line with which Picabia puts in his figures and faces, and his style as a draftsman—this is the case with his drawn figures in general—is glib and impersonal. It is borrowed Botticelli.

Picabia’s most bizarre phase arrived during the middle years of the 1930s, when he seemed to try out something different with each new canvas. None of the examples from this time that are in the show is exactly winning, but a viewer stands amazed at Picabia’s willingness to go out on one dubious limb after another. He could jump from a fairly straight representational approach—there is a portrait of Gertrude Stein in this vein—to versions of the Transparencies, except done with brighter, circuslike colors. A portrait from this time of a clown presents a kind of makeshift expressionism. With his green face and red nose and lips, he is like an upsetting character in an illustration in a children’s book.

There are paintings of male and female couples that might be called mock-ups for stained glass or possibly for perfume ads. One canvas with a fuzzy, pebbly paint surface gives us an allegory about the Spanish civil war involving skeletons and a smiling senorita, while in a portrait with a varnished, yellow tone of a pretty woman, her face is liberally spotted with what looks like a bad skin condition. Unless you are a dermatologist, you may recoil involuntarily from this one.

But then during World War II, Picabia, living in Vichy France, finally put together an approach of some substance. Often working from photos in magazines, including soft-core pornographic publications, he found a way (not that he was necessarily searching for it) to present the look of contemporary life. In the best known of these thickly painted images, we might see two nude smiling women in a bedroom, accompanied by a bulldog who eyes us as prospective johns, or a woman in heels and a black lace undergarment, in a barely lit room, who climbs onto a large, possibly lacquered piece of sculpture.

Including images of proper young lovers on a spring day and paintings that have little to do with sex or romance, these pictures from the early 1940s will be for many viewers the most unsettling part of the exhibition. Our knowing that Picabia painted them in Vichy France—a compromised political state sitting uneasily in an otherwise occupied country—is information we cannot quite put to one side (though the same facts seem to have no bearing on the work Henri Matisse did in the same place and time). Picabia himself was arrested for a few days in 1944 for possibly collaborating with the Nazis (nothing came of it). Even if one had little outside awareness of the era, there is something of a bad dream about the way Picabia has translated into paint the synthetic facial expressions and the glossy, waxy look of magazine photos.

That life in wartime France had to have been sinister when it wasn’t excruciating is borne out by two pictures: Hanged Pierrot, dated 1940–1941, in which Picabia seems to relish showing the debased and pathetic state of the clown, who hangs from a tree as a woman looks away, and The Adoration of the Calf, of 1941–1942, in which the animal’s head sits at the top of a person’s draped body. Beneath the creature, whose face is malignant, slit-eyed, and piggish, outstretched arms reach up in gestures of blind loyalty. This is a terrifying image of demagoguery.

Dada was about freedom, whether personal, social, or artistic, and the liberty Picabia took in reworking titillating and politically charged magazine illustrations can still be felt. But the note of his Vichy-era pictures is one of imprisonment. They give us—powerfully yet indirectly—a sense of life in a jarring, even frightening time. Picabia’s capturing this is not why people have felt in recent years that his art needed to be seen anew. Yet as one takes in a full display of his work, these pictures, with their strangely gleaming paint surfaces, and their sense of people whose feelings have been sealed off by a kind of psychological shellac, have a welcome solidity. One leaves the show wondering, in an admittedly un-Dada spirit, what place they might take in an overview of distinctive representational painting styles.

-

1

Norton, 2016. ↩

-

2

“The Growing Charm of Dada,” October 27, 2016. ↩