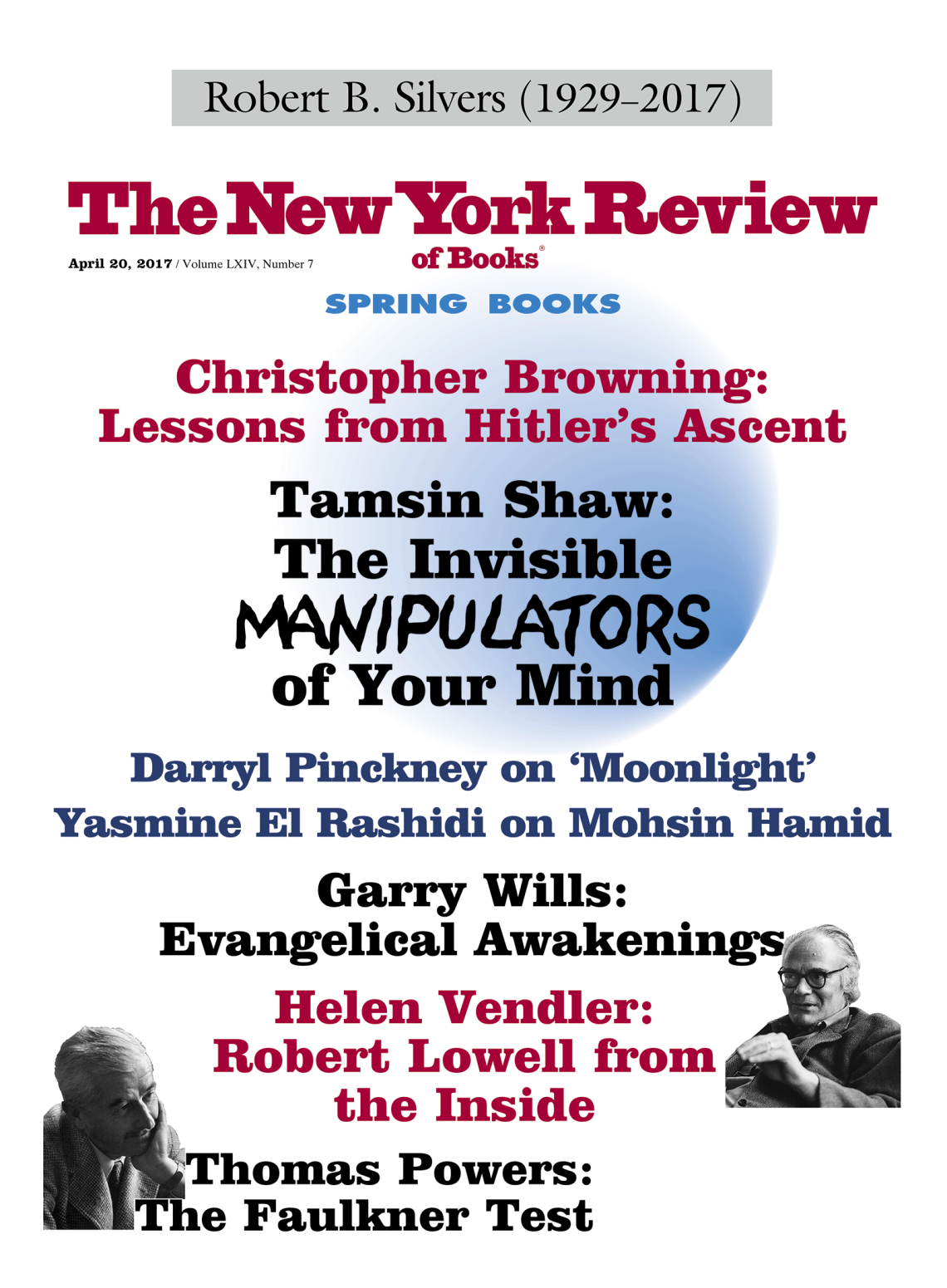

When the original German edition of Volker Ullrich’s new biography, Hitler: Ascent 1889–1939, was published in 2013, the current political situation in the United States was not remotely conceivable. The reception of a book often transcends the author’s intentions and the circumstances in which it was written, of course, but rarely so dramatically as in this case. In early 2017 it is impossible for an American to read the newly published English translation of this book outside the shadow cast by our new president.

To begin I would stipulate emphatically that Trump is not Hitler and the American Republic in the early twenty-first century is not Weimar. There are many stark differences between both the men and the historical conditions in which they ascended to power. Nonetheless there are sufficient areas of similarity in some regards to make the book chilling and insightful reading about not just the past but also the present.

Ullrich establishes that Hitler’s early life was not quite as impoverished or oppressive as he later portrayed it in Mein Kampf. Even after first his father and then his mother died, he lived on various orphan pensions and small inheritances. During periods when these resources were insufficient, Hitler did indeed lead an impoverished existence in men’s hostels, scraping out a bare subsistence by selling his paintings, and even briefly experiencing homelessness. More important was the fact that by the age of twenty-five—lacking education, career training, or job experience—he was still a man completely adrift, without any support network of family or friends, and without any future prospects. Nothing could be more different from Trump’s life of privilege, prestigious and expensive private schools, and hefty financial support from his father to enter the business world.

For Hitler, World War I was a decisive formative experience. He volunteered for the Bavarian army, endured fierce frontline combat in the fall of 1914, and then miraculously survived four years as a courier between regimental headquarters and the trenches. For Hitler the war meant structure, comradeship, and a sense of higher purpose in place of drift, loneliness, and hopelessness; and he embraced it totally. For many veterans who survived the war, it was a tragic and senseless experience never to be repeated. For Hitler the only tragedy was that Germany lost, and the war was to be refought as soon as it was strong enough to win. For Trump the Vietnam War was a minor inconvenience for which he received four deferments for education followed by a medical exemption because of bone spurs, and his self-proclaimed heroic equivalent was avoiding venereal disease despite a vigorous campaign of limitless promiscuity. In war as in childhood, Hitler and Trump could not have had more different experiences.

Ullrich takes a very commonsense approach to Hitler’s sex life, eschewing sensational allegations of highly closeted homosexuality, sexual perversion that caused him to project his self-loathing onto the Jews, asexuality commensurate with his incapacity for normal human relations, or abnormal genitalia that either psychologically or physically impeded normal sex. He surmises that Hitler (having refused to join his comrades on trips to brothels during the war) remained a virgin until at least the immediate aftermath of World War I, and remained intensely private about his relations with women thereafter.

The discreet and undemanding Eva Braun (twenty-two years his junior), consistently hidden from the public, proved to be the perfect match in facilitating Hitler’s desire to maintain the image that his total devotion to the cause transcended any mere physical needs or desires. Once again, the contrast with Trump—parading a sequence of three glamorous wives and boasting about the extent of his sexual conquests, his ability to engage in sexual assault with impunity because of his celebrity, as well as the size of his manhood—could not be starker.

In a March 1936 speech to workers at a Krupp factory in Essen, Hitler proclaimed: “I am probably the only statesman in the world who does not have a bank account. I have no stocks or shares in any company. I don’t draw any dividends.” Just as Hitler cultivated the image of transcending any physical need for the companionship of women, he also cultivated the pose of an ascetic man beyond materialistic needs. In reality he had a large Munich apartment and an expanded and refurbished mountain villa at Berchtesgaden in the Bavarian Alps, and he loved his Mercedes cars. His royalties from Mein Kampf and access to secret slush funds meant that he would never go wanting.

But these modest luxuries were not flaunted in the face of less-well-off Germans. Usefully for Hitler, the limitless greed and corruption of many of his followers, from the ostentatious Hermann Göring down to the local “little Hitlers” who utilized their newfound power to shamelessly enrich themselves, sharpened the contrast with his public asceticism. This appearance of simple living helped keep the image of the Führer untarnished, while the high living of party leaders and functionaries remained the focal point of popular resentment.

Advertisement

Once again in contrast, virtually no businessman flaunted his wealth and gold-plated name as blatantly as Donald Trump, and his entry into politics only increased the audience for this flaunting. Once elected he openly refused any of the traditional limits on conflict of interest through divestiture of his assets into a blind trust, and has filled his cabinet with fellow billionaires. The emoluments clause of the Constitution, hitherto untested due to commonly accepted axioms of American political culture, may remain so (given the Republican stranglehold on the House of Representatives through at least 2018 and very likely beyond), as Americans experience corruption, kleptocracy, and “bully capitalism” on an unprecedented scale.

If Hitler and Trump are utterly different in their childhoods and wartime experiences on the one hand and attitudes toward women and wealth on the other, the historical circumstances in which they made their political ascents exhibit partial similarities. Within the space of a single generation, German society suffered a series of extraordinary crises: four years of total war that culminated in an unexpected defeat; political revolution that replaced a semiparliamentary/semiautocratic monarchy with a democratic republic; hyperinflation that destroyed middle-class savings and mocked bourgeois values of thrift and deferred gratification while rewarding wild speculation; and finally the Great Depression, in which the unemployment rate at its worst exceeded a staggering 30 percent.

For many Germans these disasters were unnecessarily aggravated by three widespread but false perceptions: that the war had been lost because of a “stab in the back” on the home front rather than the poor decisions and reckless gambles of the military leadership; that the Versailles Treaty was a huge, undeserved, and unprecedented injustice; and that not just Communists but moderate Social Democrats, feckless liberals, and Jews—having delivered Germany to defeat and the “chains” of Versailles—threatened Germany with “Jewish Bolshevism.” According to Ullrich, it was this toxic brew that Hitler imbibed in postwar Munich, much more than his experiences in pre-war Vienna (his portrayal in Mein Kampf notwithstanding), that turned him from a complete nonentity into a rabidly anti-Semitic ideologue and radical politician.

The experience of Americans in recent years has not been one of sequential, nationwide disasters but of uneven suffering. After two protracted wars in Iraq and Afghanistan and a barely avoided total economic meltdown in 2008–2009, many Americans have enjoyed a return to comfort, security, and even prosperity, while wealth has continued to concentrate at the top. But for the sector of the population that provides the vast bulk of the recruits to our professional army, the endlessly repeated tours of duty, the inconclusive outcomes of the wars they fought, and the escalating chaos in and threat of terror from the Middle East are disheartening and demoralizing. For industrial workers and miners whose jobs have been lost to automation, globalization, and growing environmental consciousness, the post-2008 economic stagnation has meant an inescapable descent into underemployment, drastically lowered living standards, and little prospect of recovering their lost status and income.

For the first time, the life expectancy of middle-aged white Americans without a college education has significantly shortened, above all because of “diseases of despair,” especially alcoholism, drug addiction, and suicide. For social conservatives whose predominately white and Christian milieu and deference to male dominance were both taken for granted and perceived as inherent in shaping American identity, the demographic rise and political activism of nonwhite minorities, the emergence of women’s rights, and the transformation of societal attitudes toward homosexuality, especially among the younger generation, have been surprising and to many dismaying. The division of society into what the ill-fated John Edwards once called the “two Americas” has intensified. One optimistically sees America as functional and progressing, while the other pessimistically sees America as dysfunctional and declining.

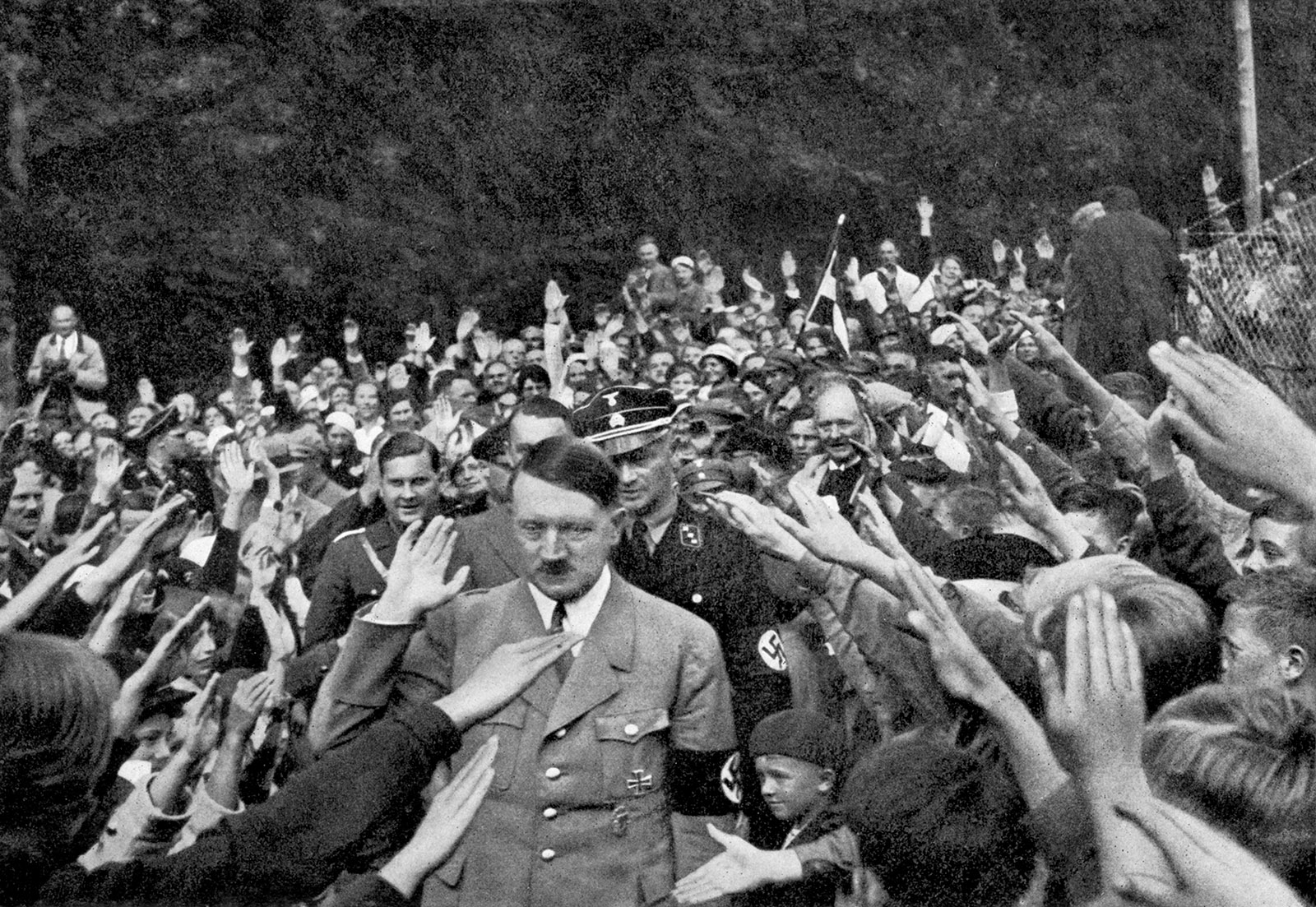

However unequal in severity the situations in the two countries were, large numbers of Germans and Americans perceived multiple crises of political gridlock, economic failure, humiliation abroad, and cultural-moral decay at home. Both Hitler and Trump proclaimed their countries to be “losers,” offered themselves as the sole solution to these crises, and pledged a return to the glories of an imagined golden past. Hitler promised a great “renewal” in Germany, Trump to “make America great again.” Both men defied old norms and invented unprecedented ways of waging their political campaigns. Both men developed a charismatic relationship with their “base” that centered on large rallies. Both emphasized their “outsider” status and railed against the establishment, privileged elites, and corrupt special interests. Both voiced grievances against enemies (Hitler’s “November criminals” and “Jewish Bolsheviks,” Trump’s “Mexican rapists,” “radical Islamic terror,” and the “dishonest” press). And both men benefited from being seriously underestimated by experts and rivals.

Advertisement

However, while both men created coalitions of discontent, their constituencies were quite different. The first groups to be taken over by Nazi majorities were student organizations on university campuses. In their electoral breakthrough in 1930, the Nazis won the vast majority of first-time voters, especially the youth vote. Above all, the Nazis vacuumed up the voters of other middle-class parties, and women of different social backgrounds voted in roughly the same proportions for the Nazis as men.

The two groups among whom the Nazis were relatively unsuccessful were Germany’s religious-block voters (in this case Catholics voting for their own Center Party) and blue-collar industrial workers (who more often shifted their votes from the declining moderate Social Democrats to the more radical Communists rather than to the Nazis). Still, the Nazis drew votes much more broadly across German society than any of their rival class- and sectarian-based parties and could boast with some justification to be the only true “people’s party” in the country.

In the end the Nazis built a strong base and won a decisive plurality in Germany’s multiparty system. The party reached 37 percent in the July 1932 elections and declined to 33 percent in November in the last two free elections, before it peaked at 44 percent in the manipulated election of March 1933.

Unlike Hitler, who won voters away from other parties to the Nazis, Trump did not build up his own party organization but captured the Republican Party through the primaries and caucuses. Despite this “hostile takeover” and Trump’s personal flaws, traditional Republicans (including women, whose defection had been wrongly predicted) solidly supported him in the general election, as did evangelicals. In contrast, the Democrats failed both to maintain Obama’s level of voter mobilization among African-Americans and youth and to hold onto blue-collar white male voters in the Great Lakes industrial states (especially in Wisconsin, Michigan, and Pennsylvania) who had voted for Obama in the two previous presidential elections, but had already deserted the Democratic Party in the previous three state elections. Trump’s 46 percent of the vote in a basically two-party race barely exceeded Hitler’s maximum of 44 percent in a multiparty race, but it was strategically distributed and thus sufficient for an electoral college victory despite Hillary Clinton’s receiving nearly three million more votes nationwide.

While Trump attained the presidency through a constitutionally legitimate electoral college victory, Hitler was unable to obtain the chancellorship through electoral triumph and a parliamentary majority. Rather he came to power through a deal brokered by Germany’s nationalist and authoritarian conservative elites and President Paul von Hindenburg. Having mobilized the large popular base that the old elites could not, Hitler was indispensable to their plans to replace the increasingly defunct Weimar democracy with authoritarian rule.

As Ullrich admirably demonstrates, it was not the inexorable rise of the Nazis but rather the first signs of their decline in the November 1932 elections (exhausted, bankrupt, and demoralized from constant campaigning without ultimate victory) that led conservative elites to accept Hitler’s demand for the chancellorship, before his stubborn holdout could ruin his own party and leave the conservatives to face the left without popular support. Many of Hitler’s and the conservatives’ goals overlapped: ending Weimar’s parliamentary democracy; rearming; throwing off the Versailles Treaty and restoring the borders of 1914; crushing the “Marxists” (i.e., Social Democrats and labor unions as well as Communists); and de-emancipating Germany’s Jews. The fundamental assumption of these conservative elites was, of course, that they would control Hitler and use him to realize their agenda, not vice versa.

Trump the populist and the traditional Republicans have likewise made a deal to work together, in part to realize those goals they share: tax “reform” with special emphasis on cuts for the well-off; deregulating business and banking; curtailing environmental protections while denying man-made climate change; appointing a Scalia-like justice to the Supreme Court; repealing Obamacare; increasing military spending; increasing the deportation of undocumented immigrants and “sealing the border”; shifting resources from public to charter schools; expanding the rights of individuals or businesses to discriminate against unprotected groups in the name of religious freedom; ending the right to abortion; and on the state level intensifying voter suppression.

It is highly unlikely, however, that Mitch McConnell, Paul Ryan, and other Republican legislators share Trump’s enthusiasm for a trillion-dollar infrastructure package; his pledge not to cut Social Security and Medicare; the replacement of broad, regional free trade agreements with narrow, bilateral trade treaties; and some economic conjuring trick to reopen closed coal mines, steel mills, and factories. Presumably some of these Trump promises will be set aside (as already appears to be happening to his promise of a health plan that covers more people with better care at less cost, though not sufficiently to the satisfaction of hard-core conservatives), and further conflict looms ahead.

If both Hitler and Trump made deals with conservative political partners on the basis of partially overlapping goals and those partners’ wishful thinking, it is simply not possible for Trump to consolidate absolute power and dispense with his allies with either the speed or totality that Hitler did. One of the most chilling sections of Ullrich’s biography deals with the construction of the Nazi dictatorship. Through emergency decrees of President Hindenburg (not subject to judicial review), freedom of the press, speech, and assembly were suspended within the first week. Due process of law and the autonomy of state governments were gone within the first month, as the government was empowered to intern people indefinitely in concentration camps without charges, trial, or sentence, and to replace non-Nazi state governments with Nazi commissioners. By the sixth week, the Communist Party had been outlawed and the entire constitution had been set aside in favor of Hitler (rather than Hindenburg) ruling through decree.

In the third month equality before the law was abrogated with the first anti-Jewish decrees and the purging of the civil service, and in the fourth month the labor unions and the Social Democratic Party were abolished. The remaining political parties disbanded themselves in month five. In June 1934 Hitler carried out the “Blood Purge.” Among its victims were former chancellor Kurt von Schleicher and his wife as well as hundreds of others on Hitler’s enemies list. Former vice chancellor Franz von Papen, who had brokered the deal that brought Hitler to power, was dispatched as ambassador to Austria. It was as if Hillary and Bill Clinton were gunned down in their doorway, and Mike Pence sent off as ambassador to Canada.

Partly because Trump does not have an independent party and paramilitary militia totally committed to him personally and partly because American democracy is in no way as atrophied as was the Weimar Republic, such a whirlwind creation of dictatorship is not a possibility in 2017. Courts continue to exercise judicial review and uphold due process, governors in states like California and Washington are not being deposed and replaced, the exercise of free speech, press, and assembly under the Bill of Rights is still intact, and opposition parties are not being outlawed. Equally important, large numbers of people are frequently and visibly exercising their rights of assembly and speech, and the news media have not sought to ingratiate themselves with the new regime, thereby earning the administration’s reprimand that they are both the real “opposition” and the “enemy of the people.” Whatever the authoritarian tendencies of Trump and some of those around him, they have encountered limits that Hitler did not.

Two factors that Ullrich consistently emphasizes are Hitler’s ideological core on the one hand and the fact that he made no attempt to hide it on the other. On the contrary, knowledge of it was available to anyone who cared enough to look. If Hitler’s first postwar biographer, Alan Bullock, treated him as a tyrant seeking power for its own sake, Ullrich embraces the research of the late 1960s, especially by Eberhard Jäckel,* who laid out how, over the course of the 1920s, Hitler’s worldview crystallized around race as the driving force of history. He believed the Jews constituted the greatest threat to Germany’s racial purity and fighting spirit, and thus to its capacity to wage the eternal struggle for “living space” needed to sustain and expand Germany’s population and vanquish its rivals.

Ullrich also accepts later research that demonstrates that this worldview did not constitute a premeditated program or blueprint, but provided the parameters and guidelines for how Nazi racial, foreign, and military policy evolved and radicalized over the twelve years of the Third Reich. Ascent ends in March 1939, with the occupation of Prague as Hitler’s last bloodless victory. But it is clear to Ullrich that no one should have been surprised that Hitler’s ideologically driven career was destined to culminate in war and genocide.

With Trump, of course, we have neither historical perspective nor discernible ideological core. The overwhelming impression is that his ego and need for adulation, as well as his inability to discern simple reality and tell the truth when his ego is threatened, are his driving forces, not ideology. Among his appointees, however, is the Breitbart faction of Steve Bannon and Stephen Miller, who embrace a vision of what Bannon euphemistically calls “economic nationalism.” It combines white supremacy; the Leninist “deconstruction” of the New Deal/cold war administrative state; Islamophobia (especially in seeing a titanic and irreconcilable clash of civilizations between Islam and the West); the dismantling of the current international order (UN, EU, NATO, NAFTA, etc.) in favor of a return to unfettered and self-assertive, ethnically homogeneous nation-states; affinity with Putin’s Russia and other ultra-nationalist and increasingly authoritarian movements in Europe; and apocalyptic historical thinking about the end of the current era (a roughly eighty-year cycle that began in the 1930s) and the emergence of a new one in the very near future.

Trump shares these views sufficiently to have made Bannon the chief strategist of his administration, and his easy resort to racist rhetoric—the birther myth, Mexicans as rapists and criminals, the Muslim ban, Lindbergh’s “America First” slogan—makes clear that he is perfectly comfortable stoking racism. But it is not clear if any of this ideological package would have priority over his central agenda of self-aggrandizement. The future direction of the Trump administration depends in no small part on the extent to which the Bannon-Miller faction prevails over the collection of traditionalists, military officers, and billionaires whom Trump has also appointed to important positions.

Ullrich also shows that the phenomenal rise in Hitler’s popularity—his ability to win over the majority of the majority who did not vote for him—crucially resulted from the dual achievement of a string of bloodless foreign policy victories on the one hand and economic recovery (especially the return to full employment) on the other. Full employment was accomplished above all by rearmament through huge deficit spending and enormous trade deficits that resulted from bilateral trade deals. They created an economic house of cards in which the frenetic pace of preparing for a major war planned for 1942–1943 required the gamble of seizing Austrian and Czech resources while avoiding war in 1938–1939. The infrastructure program of building autobahns had a very minor, mostly cosmetic, part in economic recovery.

Trump too has staked his political future on economic promises of 4 percent growth; the reopening of coal mines, steel mills, and factories in regions of economic blight; and the replacement or renegotiation of free trade agreements (that were based on the assumption of mutual benefit) with bilateral trade deals in which America wins and the other side loses. In this regard the goal of his bilateral trade agreements is exactly the opposite of Hitler’s, i.e., he seeks trade surpluses, while Hitler paid for crash rearmament in part through trade deficits that would allegedly be paid off later or preferably canceled through conquest. Trump is tied to a political party that traditionally has favored free trade and abhors deficit spending for any purposes other than providing tax cuts for the wealthy, increasing the military budget, and justifying cuts to the welfare safety net.

It is unclear how Trump’s populist promises on health care, Social Security and Medicare, infrastructure rebuilding, and recovery of blighted industries can be accomplished, particularly in an environment of potential trade war, higher cost of living due to import taxes and diminished competition, possible decline in now relatively prosperous, cutting-edge export industries, and agrobusiness that needs both export markets and cheap immigrant labor. Tax cuts, deregulation, and reckless disregard for the environment are the Republican panaceas for the economy. Will they provide even a temporary boost (before the balloon bursts and the bill comes due as it did for George W. Bush in 2007–2008) sufficient to help Trump escape the economic and political cul de sac into which he has maneuvered himself? Here too the future direction of the Trump administration is unclear.

Hitler and National Socialism should not be seen as the normal historical template for authoritarian rule, risky foreign policy, and persecution of minorities, for they constitute an extreme case of totalitarian dictatorship, limitless aggression, and genocide. They should not be lightly invoked or trivialized through facile comparison. Nonetheless, even if there are many significant differences between Hitler and Trump and their respective historical circumstances, what conclusions can the reader of Volker Ullrich’s new biography reach that offer insight into our current situation?

First, there is a high price to pay for consistently underestimating a charismatic political outsider just because one finds by one’s own standards and assumptions (in my case those of a liberal academic) his character flawed, his ideas repulsive, and his appeal incomprehensible. And that is important not only for the period of his improbable rise to power but even more so once he has attained it. Second, putting economically desperate people back to work by any means will purchase a leader considerable forgiveness for whatever other shortcomings emerge and at least passive support for any other goals he pursues. As James Carville advised the 1992 Clinton campaign, “It’s the economy, stupid.” Third, the assumption that conservative, traditionalist allies—however indispensable initially—will hold such upstart leaders in check is dangerously wishful thinking. If conservatives cannot gain power on their own without the partnership and popular support of such upstarts, their subsequent capacity to control these upstarts is dubious at best.

Fourth, the best line of defense of a democracy must be at the first point of attack. Weimar parliamentary government had been supplanted by presidentially appointed chancellors ruling through the emergency decree powers of an antidemocratic president since 1930. In 1933 Hitler simply used this post-democratic stopgap system to install a totalitarian dictatorship with incredible speed and without serious opposition. If we can still effectively protect American democracy from dictatorship, then certainly one lesson from the study of the demise of Weimar and the ascent of Hitler is how important it is to do it early.

-

*

Eberhard Jäckel, Hitler’s Weltanschauung: A Blueprint for Power (Wesleyan University Press, 1972), originally published in German in 1969. ↩