If anyone thought that Donald Trump’s manifold inconsistencies might more or less randomly offer women some protection from the Mike Pence wing of the Republican Party—after all, Trump once said of himself, “I’m very pro-choice”—they were wrong. Trump, who was once in thrall to his resident misogynist Steve Bannon, remains dependent on Pence, his omnipresent minder, and women’s reproductive rights are in his sights.

Women have always been subject to male domination, sometimes almost completely. Even in as enlightened a country as the United States, men created the laws under which women lived well into the twentieth century, and they ensured that women had an inferior status. Shirley Chisholm, the African-American congresswoman who ran for president in 1972, famously said that of her two handicaps—being black and being a woman—“I have certainly met much more discrimination in terms of being a woman than being black, in the field of politics.”

Women couldn’t vote in the United States until 1920 (fifty years after African-American men), and until 1936 they could lose their citizenship if they married a foreigner and lived abroad. As for their children, citizenship was conferred by the father, not the mother. Until 1968, job ads could specify whether men or women would be hired, and that year women were paid on average 58 cents for every dollar earned by men. Remarkably, women could be denied credit without a man’s signature until 1974, and until 1978 they could be fired from their jobs if they became pregnant.

Not surprisingly, controlling sexuality and reproduction was central to keeping women in their place. For most of the country’s history, motherhood was considered women’s highest calling. They were expected to submit to their husbands sexually, and marital rape did not become a crime in all states until 1993. Abortion was illegal in most of the country for most of its history. Desperate women would take various folk remedies to end a pregnancy, try to end it themselves with some contrived implement, or find an illegal abortionist—all risky. There are no reliable figures for how many women died from illegal abortions but almost certainly there were many.

Until 1960, abstinence was expected for single women, and if that didn’t suit them, they were pretty much on their own. Getting fitted for a diaphragm was a ritual mainly for women engaged to be married. The only other forms of contraception were withdrawal, abstinence during the likely time of ovulation, and condoms; late menstrual periods could be terrifying. If a single woman did become pregnant, then what? Single motherhood was seldom contemplated, at least for a middle-class woman. Instead she might hope that her partner would marry her quickly, or she might try to get an illegal abortion. (The language of those days was appropriately evocative—“back-alley abortions” and “shotgun marriages.”) Often, she would be sent to a “home for unwed mothers,” where she would stay until her baby was born, maybe under cover of some story about going away for a few months to care for a sick relative in a distant town. After the baby was born, it would usually be given up for adoption. (Many of these places ran lucrative adoption businesses.)

Everything changed in 1960 when the first birth control pill, Enovid, came on the market. The impact can hardly be overstated. Despite the fact that a prescription was required, which could be embarrassing and even difficult for single women to get from paternalistic doctors, within a few years millions of women were “on the pill.” For the first time, they had access to a reliable means of contraception that they controlled, and so were free to plan their own lives to an extent not possible earlier. Later, implantable contraceptives, intrauterine devices, and the “morning after” pill, known as Plan B (now available without a prescription), added new ways to prevent pregnancy. Nevertheless, many pregnancies continued to be unplanned, and still are.

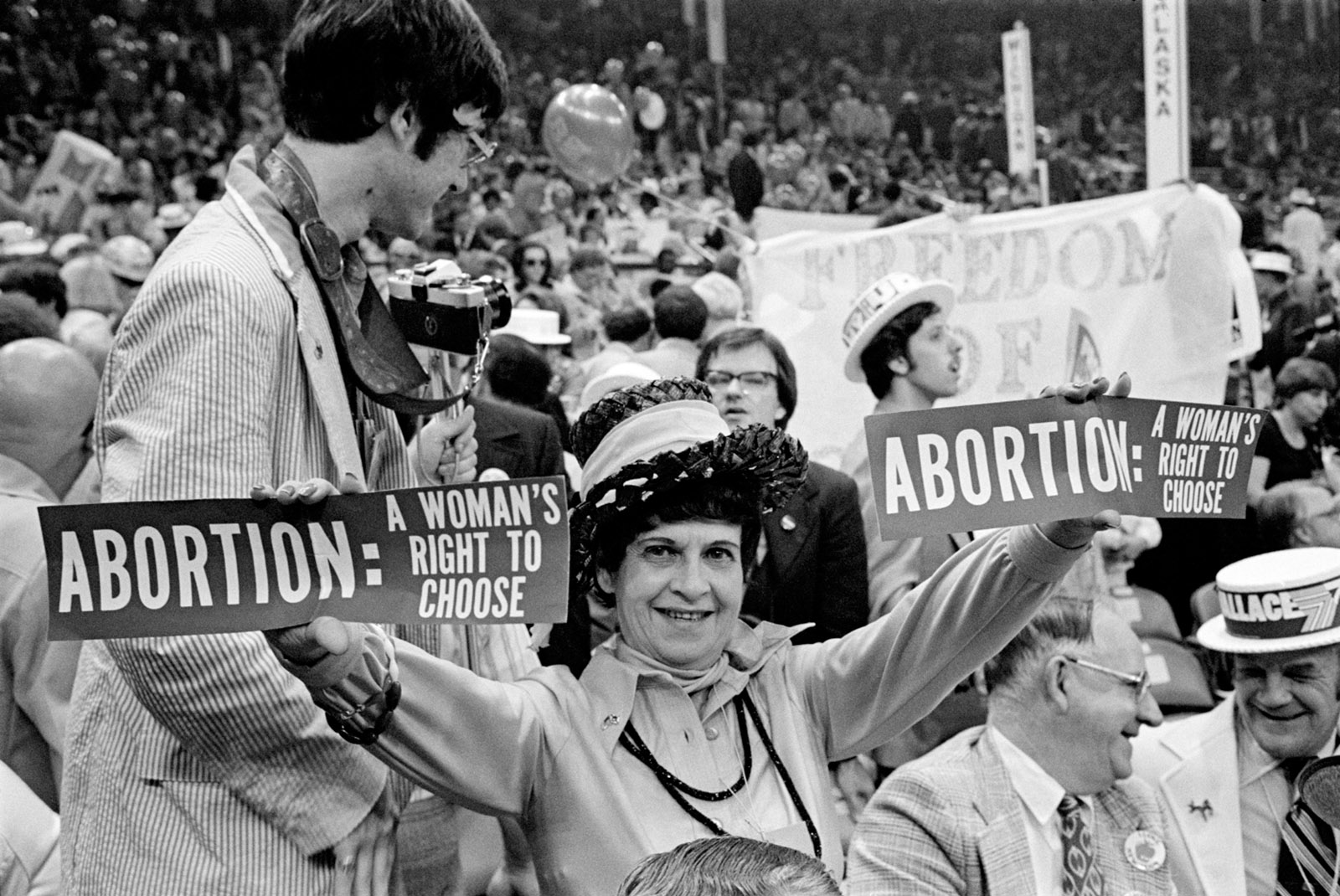

In 1973 the Supreme Court, in the case of Roe v. Wade, took the next step. It found by a 7–2 majority that women had a constitutional right to end a pregnancy. The right was close to absolute in the first trimester, could be regulated by the states in the second trimester only to protect the woman’s health, and in the third trimester could be further regulated or even banned to protect “potential life,” unless the woman’s health or life were at stake. Legal abortions rapidly became common. According to the Guttmacher Institute (a research institution that gathers data on reproductive health in the US), about 3 percent of women in the United States had legal abortions in 1980 (one of the peak years), and it was later estimated that roughly a third of American women would obtain an abortion at some time in their lives.

Advertisement

Almost immediately, Roe v. Wade became a moral and political—and sometimes a literal—battlefield, and it remains so. Two excellent books, Women Against Abortion: Inside the Largest Moral Reform Movement of the Twentieth Century, by Karissa Haugeberg, and About Abortion: Terminating Pregnancy in Twenty-First-Century America, by Carol Sanger, tell the story. Both authors support abortion rights, but they also present the opposition to abortion fairly and, in the case of Haugeberg, sometimes sympathetically.

Some of the most vociferous and effective opponents of abortion have been women, and Haugeberg focuses on them. Through their eyes we see what moved them, and through their activities, the increasing violence of the movement. Sanger’s book is broader and more philosophical. She is interested in the whole panoply of issues around abortion—its history and the laws regulating it, who has abortions and why, how state legislatures and the courts are eroding its availability, the rights (if any) of pregnant minors and of fathers, and, perhaps most interesting, why a perfectly legal procedure is still in the shadows. Her observations are nearly always insightful and often nicely trenchant. She writes, for example, that a prohibition against abortion that makes exceptions for rape or incest “produces a rather sharp inequality among fetuses.”

According to Haugeberg, the initial public opposition to abortion, which began even before Roe v. Wade, came from priests and bishops in the Catholic Church, as well as Catholic women, often nuns, whose opposition frequently grew out of their general reverence for life (many had been involved in antiwar activities in the 1960s). It was only later that the term “pro-life” became more a political label than a statement of purpose, since it tended no longer to encompass the loss of life from wars or executions.

In addition, antiabortion organizations were formed, such as the National Right to Life Committee (NRLC), which had millions of members and chapters in every state by the late 1970s. Like the Catholic Church, their focus was on protecting the embryo (defined as less than eight weeks’ gestation) or fetus—both usually referred to as the “unborn child”—through legal and legislative strategies.

But beginning in the late 1970s, there was an ideological shift. Instead of emphasizing only the protection of the fetus, the focus changed to include the protection of pregnant women. In essence, they were seen as potential victims of heartless abortionists, as much at risk as their fetuses. A new psychological illness, called the postabortion syndrome, was invented, marked by lifelong guilt and remorse after an abortion. (According to Sanger, the most commonly reported feeling after an abortion is actually relief.) Justice Anthony Kennedy’s majority decision, when the Supreme Court upheld a law against certain late-term abortions in 2007, echoed that notion:

While we find no reliable data to measure the phenomenon, it seems unexceptionable to conclude that some women come to regret their choice to abort…. Severe depression and loss of self-esteem can follow.

He offered no evidence, nor did he address the possibility of severe depression or loss of self-esteem from having to continue an unwanted pregnancy.

This shift gave new importance to facilities that had emerged in the 1960s called crisis pregnancy centers (CPCs). According to Haugeberg, these “were a uniquely woman-dominated sector of the antiabortion movement.” Often located near abortion clinics, they were designed to look like them. But instead of providing abortions, CPCs offered free pregnancy tests, then tried to dissuade pregnant women from obtaining abortions. They rapidly became the major form of activism, writes Haugeberg, and by 2009, there were 3,200 of these facilities, with a combined staff of 40,000, and they saw about one million pregnant women each year. After 1995, CPCs became partially federally funded.

By the 1980s, the antiabortion movement had undergone another major shift. It became dominated not by Catholics but, over time, by evangelical Protestants, and its methods increasingly included direct confrontations at abortion clinics to block access. The movement also became increasingly associated with the right wing of the Republican Party, which as far back as the Eisenhower administration had set out to win over religious and social conservatives. The 1980 Republican platform called for a constitutional amendment to protect the life of the unborn, and the new president, Ronald Reagan, who, like Trump, had once favored abortion, now, like Trump, opposed it.

In 1986 an evangelical Protestant minister, Randall Terry, started an organization called Operation Rescue, which advocated stopping abortions by nearly any means possible, including firebombing clinics and harassing and threatening clinic doctors and staff and their families. There were more than 60,000 arrests at Operation Rescue actions, according to Haugeberg, and the organization went bankrupt within a few years because of the mounting number of lawsuits. But the turn toward violence continued. There were “Wanted” leaflets posted for Dr. David Gunn, for example, describing him as a “circuit riding abortionist,” and giving his address, car make, and license number, other personal details, and the address of his clinic—where he “kills children.” Gunn was murdered in 1993 by an antiabortion activist named Michael Griffin. One of Griffin’s apologists said, “Defending Michael Griffin’s action came naturally to me. Babies were not murdered on the day David Gunn was shot and a serial killer would never kill again.”

Advertisement

One problem was the lax attitude toward law enforcement at abortion clinics. Firebombing and arson were treated as isolated incidents, and the perpetrators were lightly punished, sometimes again and again. One repeat offender was Shelley Shannon, who was eventually sentenced to eleven years in prison for the attempted first-degree murder of Dr. George Tiller, an abortion provider, but in the five years before that, according to Haugeberg, she had been “arrested nearly fifty times and charged with a crime thirty-five times, usually trespassing. When she was found guilty, she was typically sentenced to perform community service or serve up to thirty days in jail and to pay nominal fines.”

The murder of Dr. Gunn prompted Congress to pass the Freedom of Access to Clinic Entrances (FACE) Act in 1994. President Clinton, the first president to support abortion rights unambivalently, directed his cabinet to investigate and prosecute activists who interfered with the provision of abortion services. His attorney general, Janet Reno, authorized the FBI to investigate whether Shannon had assistance when she firebombed clinics, and directed federal marshals to protect endangered clinics after two more abortion providers were murdered in 1994.

Haugeberg devotes most of a chapter in her book to Shannon—a sobering account of how an unexceptional young woman became an increasingly violent fanatic. Her motivation, as she said repeatedly, was to save the lives of “unborn children.” In her trial for attempted murder, she explained it this way:

I believe there are occasions when a person becomes so evil and perhaps to stop the crimes they’re causing or to stop them from murdering all kinds of other people, such as in the case of Hitler…it may take something like their death to stop what they’re doing.

But there was also a grisly aspect to her. Haugeberg writes:

Shannon and her comrades encouraged pro-lifers to exact physical pain and suffering on abortion providers “by removing their hands, or at least their thumbs below the second digit.”

Shannon, still in prison and a heroine to the extreme wing of the pro-life movement, was intensely devoted to her network of fellow zealots, which seems to have been dominated by men.

When it became more difficult to confront doctors at their clinics because of better protection, antiabortion extremists found them at their homes and churches. After Shannon’s attempt on his life, George Tiller was later murdered in his church by a friend of Shannon’s. Another doctor, Barnett Slepian, wrote about the intimidation he experienced:

The members of the local non-violent pro-life community may continue to picket my home wearing large “Slepian Kills Children” buttons, which they did on July 25. They may also display the six-foot banner…. They may continue to scream that I am a murderer and a killer when I enter the clinics at which they “peacefully” exercise their First Amendment Right of freedom of speech…. But please don’t feign surprise, dismay and certainly not innocence when a more volatile and less restrained member of the group decides to react to their inflammatory rhetoric by shooting an abortion provider. They all share the blame.

Four years later, Slepian was murdered at his home. The total count between 1978 and 2015, writes Haugeberg, was eleven murders (nine of them physicians), twenty-six attempted murders, 185 arsons, forty-two bombings, and 1,534 vandalizations of clinics.

The attention of antiabortion advocates also turned to legislative efforts to restrict the right to abortion, with the hope of regulating it out of existence. Many states, particularly Republican strongholds, began to pass legislation that put onerous and often humiliating conditions on women seeking abortions and on the doctors providing them. In the 1992 case of Planned Parenthood v. Casey, the Supreme Court considered a challenge to the Pennsylvania Abortion Control Act, which set a twenty-four-hour waiting period for women seeking abortions, and required doctors to provide them with information designed to dissuade them from their decision. Although the Court affirmed a constitutional right to abortion, which could not face an “undue burden,” it eroded that right substantially. As Sanger writes:

The Court announced that Roe had undervalued the state’s interest in potential unborn life, an interest which Casey now fixed at the moment of conception. States were now within their rights to persuade pregnant women against abortion from the start.

The trimester system of Roe v. Wade, in which fetal interests came into play only in the third trimester, was gone.

Since then, and particularly since Republicans have gained control of most state governments, states have rushed to pass new laws that treat pregnant women like errant children. According to Haugeberg, “Between the 2010 midterm elections and 2015, states adopted 231 new restrictions on abortion.”

Consider Alabama’s Women’s Right to Know Act. It requires a twenty-four-hour waiting period prior to an abortion. Before the procedure, the physician must first perform an ultrasound examination of the fetus, and must ask the woman if she would like to see the image. After the procedure, she must complete a form acknowledging either that she looked at the image of her fetus or that she was “offered the opportunity and rejected it.” Ten states have enacted similar legislation. Some include a requirement that the physician describe the fetus in detail to the woman.

Texas went even further. It added two more requirements to its already daunting restrictions. The first required all abortion providers to have admitting privileges at a local hospital, and the second required all abortion clinics to be licensed as “ambulatory surgical centers,” essentially mini-hospitals. These requirements would put many abortion clinics out of business, as the legislators well knew—and intended. The case eventually reached the Supreme Court, which held in Whole Women’s Health v. Hellerstedt (2016) that these additional requirements put an “undue burden” on the exercise of a constitutional right—one of the few pieces of good news in recent years for defenders of abortion rights.

Still, about half the abortion clinics in Texas have had to close, as have many in other states. According to the Guttmacher Institute, 95 percent of abortions are performed in freestanding clinics, not in hospitals or doctors’ offices, so widespread closures have an enormous impact. Sanger is strong in her denunciation of the state restrictions. She points out that life-changing decisions are made every day without the requirement for waiting periods, and that to require them here implies that pregnant women are impulsive and don’t know their own minds. She also opposes the requirement for ultrasound examinations—“should women be made to offer up the content of their bodies in the form of an image for inspection before the law permits them to end a pregnancy?”—and for doctors to impart state-specified information to their patients.

Most telling, Sanger highlights the failure of those who favor the restrictions, ostensibly because of the harms abortion causes, to consider the harms of not being able to obtain one. For many women, an unwanted pregnancy can be disastrous—emotionally, financially, or even physically (the mortality rate from childbirth is about ten times that of an abortion), and there are now concerns about a resurgence of self-induced abortions in regions where abortion clinics have closed. Moreover, there has been almost no consideration of the possible harms to children whose mothers didn’t want them.

The latest figures from the Guttmacher Institute are for 2014. They show a rapid drop in abortions to the lowest level since Roe v. Wade, about half the frequency from the peak in 1980. The decline probably reflects better methods of contraception, but it is likely that it also reflects the growing difficulties in obtaining abortions.

The reasons most women gave the researchers for choosing an abortion were concern for someone else, inability to afford raising a child, and the belief that having a baby would interfere with work, school, or the ability to care for dependents. The great majority had incomes of less than 200 percent of the federal poverty level, and nearly 60 percent already had given birth to at least one child. About half were single. In 1977, Congress barred Medicaid from using federal funds to pay for abortion services, but fifteen states permit state funds to be used. Still, most women in 2014 paid for the procedure out-of-pocket.

As for the ages of women who had abortions, 61 percent were in their twenties, 8 percent were eighteen or nineteen, 3 percent were fifteen to seventeen, and 0.2 percent were younger than fifteen. Depending on the state, girls under age eighteen must either notify or get consent from their parents for an abortion, or, alternatively, petition a judge to get permission. The judge’s task in these hearings is to determine if the minor is sufficiently mature and well informed to make her own decision. If so, she may get an abortion without her parents’ consent or knowledge. But if not, then what? Presumably, as Sanger writes, this immature and uninformed girl “marches on to motherhood,” depending on the judge.

An important new development is the growing use of medical abortions performed using two drugs, mifepristone (Mifeprex) and misoprostal, given two days apart, that induce a miscarriage. Although mifepristone was approved by the FDA in 2000 for early abortions, the agency attached a number of restrictions to its dispensation, ostensibly for safety reasons. For example, it can be dispensed only by a specially certified prescriber in clinics, medical offices, or hospitals. Nevertheless, about 30 percent of abortions are no longer surgical, but medical—that is, performed using these drugs. Medical abortions will almost certainly become more important as surgical procedures continue to decline. Moreover, a recent article in The New England Journal of Medicine by experts in the field—the Mifeprex REMS Study Group—argues convincingly that the restrictions on the dispensation of the drugs are unnecessary and should be lifted.1

Sanger is at her best and most original in discussing the secrecy surrounding abortions, which she sees as the biggest obstacle to public acceptance. Her argument is that even though abortion is legal, women who have an abortion tend to behave as though it weren’t. They keep it a secret even from their friends in a way that goes beyond privacy, and suggests fear of recrimination. The fact that clinics are isolated from the medical facilities that provide most other health care adds to the furtiveness, as does the fact that courts use pseudonyms (as in Roe2) in abortion cases, which Sanger, quoting one court decision, notes is permitted only when there is “some social stigma or the threat of physical harm to the plaintiffs….”

She believes women should talk openly about having had an abortion, in the same way that other once-closeted subjects, such as depression, being gay, getting divorced, miscarriage and stillbirth, even breast cancer, were normalized through both private and public disclosure. “The absence of private discussion distorts the nature of public debate, which in turn distorts the political discourse that informs legislative processes,” Sanger writes, and further, “secrecy hides potential solidarity or resolution.”

A Pew poll in October 2016 showed that 59 percent of Americans think abortion should be legal in all or most cases, while 37 percent think it should be illegal in all or most cases. (This is one of a number of contentious issues about which the public is very far removed from its Republican-dominated government.) It seems to me that much of the argumentation about abortion hinges on the use of loaded words, in particular the word “life.” If life is defined as beginning at conception, then it is often assumed that abortion should therefore be illegal. But that doesn’t necessarily follow. Most abortions occur before eight weeks of pregnancy, before the embryo is even mature enough to be called a fetus, and although it is technically alive, it is a very primitive form of life. Whether the argument for its preservation outweighs the concerns of the pregnant woman may be a reasonable question, but the moral argument would go better without the notion that the answer follows from the word.

The Trump administration has made it clear that it, along with the Republican Congress, will do everything possible to bring an end to abortion. Consider the omens: one of Trump’s first executive orders was to stop funding for overseas medical facilities that even mention abortion as an option. His attorney general, Jeff Sessions, referred to Roe v. Wade as “one of the worst, colossally erroneous Supreme Court decisions of all time.” The new Congress is poised to eliminate federal funding for Planned Parenthood, the largest provider of reproductive health care services in the United States—which includes cancer screening and contraception as well as abortions. As governor of Indiana, Vice President Pence signed one of the most restrictive of the state abortion laws. “I long for the day,” he has said, “that Roe v. Wade is sent to the ash heap of history.” If Neil Gorsuch, Trump’s addition to the Supreme Court, is in agreement, which is likely, Roe v. Wade could be overturned or further eroded if a relevant case comes before the Court.

In the past half-century, women have made giant strides toward equality, and there is no question that a major reason is the availability of reliable contraception and safe and legal abortions. Women now earn more undergraduate and graduate degrees than men and are closing the income gap (from 58 cents to a man’s dollar in 1968 to 78 cents in 2013). But they have not reached parity, and there is still a glass ceiling. Moreover, further progress is not inevitable, and change does not move in only one direction. We can go backward as well as forward—something Iranian women experienced in 1979, and Afghan women in the 1990s. It will take awareness of the fragility of progress, as well as political action, to stop the Trump administration from turning back the clock.

This Issue

June 22, 2017

Louis Kahn’s Mystic Monumentality

The Male Impersonator

-

1

“Sixteen Years of Overregulation: Time to Unburden Mifeprex,” The New England Journal of Medicine, February 23, 2017. ↩

-

2

The plaintiff in Roe v. Wade was Norma McCorvey, who, after becoming a born-again Christian and later a Catholic, turned against the abortion rights she had won in 1973. She died on February 18, 2017. ↩