In response to:

Did Emotions Cause the Terror? from the June 22, 2017 issue

To the Editors:

Colin Jones, in his review of Timothy Tackett’s The Coming of the Terror in the French Revolution [NYR, June 22], ignores the role of the popular movement on the left that opposed the dictatorship of Maximilien Robespierre and the Terror. Neither Tackett nor Jones is unusual in this.

In particular, the role of the most important opposition group, La Société des Citoyennes Républicaines Révolutionnaires (The Society of Revolutionary Republican Women), is completely ignored. There are two serious histories of this movement in French: Daniel Guérin’s La Lutte des classes sous la première République: Bourgeois et “bras nus” and Le Club des Citoyennes Républicaines Révolutionnaires by Marie Cerrati. A recent book in English by Hal Draper, Women and Class, includes a discussion of this movement. Albert Soboul’s The French Revolution 1787–1799, also in English, briefly notes that the club, and all other women’s clubs, were abolished by Robespierre on October 30, 1793.

The history of the popular movement in the French Revolution is one that has been largely ignored.

E. Haberkern

Berkeley, California

To the Editors:

Colin Jones’s review of Timothy Tackett’s The Coming of the Terror in the French Revolution presents us with some curious propositions. Undoubtedly, human emotions fueled the passage of the French people from the legitimate assertion of the public interest versus the royal prerogatives in 1789 to the wholesale scapegoating of the royalist class as well as fellow revolutionists caught up the frenzy of terror in 1793. But how do we understand the structure of these emotions and their origin in the public consciousness?

That question takes us from intellectual history to the realm of behavioral and social science. And prompts another question: Must revolutionary movements take such destructive—and ultimately self-destructive—measures as part of their evolution?

It doesn’t have to go in that direction—as our recent study of group behavior demonstrates (Group Dynamics and the New Heroism: The Ethical Alternative to the Stanford Prison Experiment).

The norms of group behavior are set from the top and communicated both explicitly and implicitly, verbally and nonverbally. In this social context, the emotional content of a group is carried by specific leadership roles that emerge from the group as part of its organizational structure and process of formation. One of the most salient features of this paradigm is the scapegoat leadership role that can either summon a spirit of collective acceptance and inclusion or lead to suspicion, paranoia, and murder. How the scapegoating behavior is managed by the task leaders is the determining factor.

Historians and social psychologists as distinct disciplines have not enjoyed much cross-fertilization. But there may be room for fruitful collaboration when investigating the structure of revolutionary leadership.

Bill Roller and Philip Zimbardo

Berkeley, California

Colin Jones replies:

Timothy Tackett’s The Coming of the Terror in the French Revolution seeks to go beyond factional maneuverings in 1793 to focus on how apparently perfectly respectable members of the middling classes were drawn toward acceptance of actions from which they would ordinarily have shrunk in horror. He wants to understand that acceptance from the inside, moreover, as a felt phenomenon, and thus draws on the diaries and letters of ordinary men and women (who inevitably therefore are predominantly from the literate classes).

This emphasis on the emotional life of what historians used to call the Revolutionary bourgeoisie is pertinent and welcome in that it rejects most earlier discussions of emotions in the Revolution, which luridly highlighted the allegedly irrational, hysterical, and bloodthirsty motivations of the lower classes, particularly women in fact. Far from “completely ignoring” the Society for Revolutionary Republican Women, moreover, Tackett cites it on multiple occasions, highlighting the ways that it inspired and pioneered a set of feminist demands that remain brightly relevant in our own day. He is surely correct, however, not to view the society as “the most important oppositional group” at the time. It comprised less than two hundred members, had very limited influence within Paris, and developed a fluctuating political agenda over its short life of a few months before it was crushed in late 1793—to disappointingly low levels of popular protest.

Like Dr. Zimbardo and Mr. Roller, I too somewhat regret that Tackett’s history of the emotions in the Revolution fails to signal what the field might gain from interdisciplinary links to social psychology. In my review, I noted that he did not utilize the work of William Reddy, whose study of eighteenth-century France (notably The Navigation of Feeling, 2001) draws heavily on social science methodologies. Tackett’s own approach adapts the medieval historian Barbara Rosenwein’s idea of “emotional communities,” a concept that might offer bridges into the kind of leadership studies cited by Roller and Zimbardo.

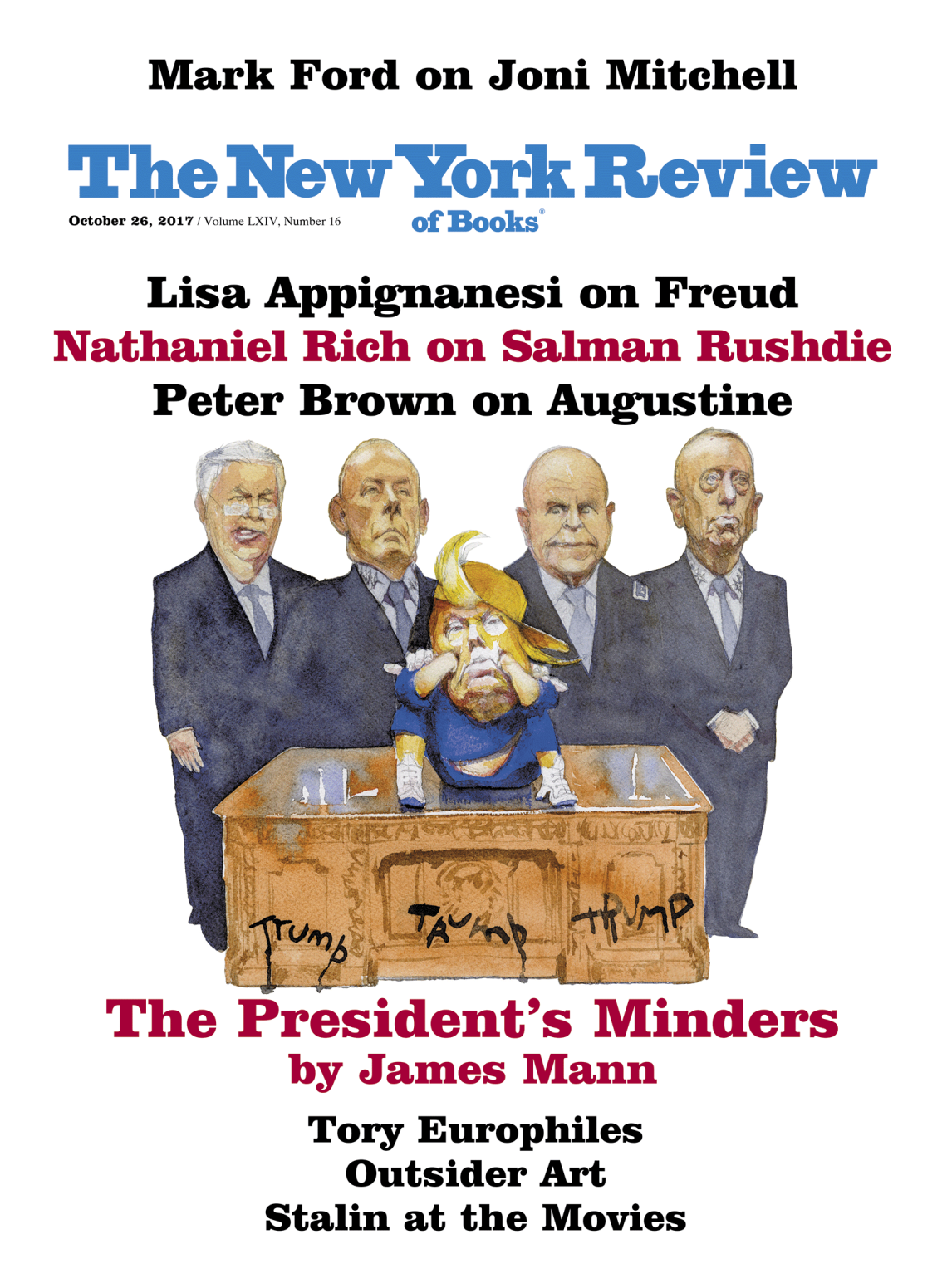

This Issue

October 26, 2017

Rushdie’s New York Bubble

The Adults in the Room

Dialogue With God