In 2012, Sarah Ruden brought us, in a crackling translation, the second-century-AD Latin novel known as The Golden Ass of Apuleius. The Golden Ass is full of impudent incongruities. A topsy-turvy tale about a hapless young man turned into a donkey is combined with a love story (of Cupid and Psyche) as bright and delightful as the tapestries that would illustrate it throughout the late Middle Ages and the Renaissance. Utterly unexpectedly, the book ends with the vision of a goddess rising from the swell of a moonlit sea.1

Ruden now leads us to a yet more incongruous masterpiece. A little over two centuries after The Golden Ass, we discover a person who appears to be a highly Latinate North African such as Apuleius had been—a product, indeed, of a school established in Apuleius’s own hometown, Madauros (modern M’Daourouch, in Algeria, near the tense border with Tunisia)—only to learn that he was a middle-aged Christian bishop, with his back turned to us, speaking endlessly, urgently to his God.

We call this riveting dialogue with God the Confessions of Saint Augustine. It was probably written in 397 AD, a few years after Augustine had become a Christian bishop in Hippo (modern Annaba, in Algeria: one of the few good ports available west of Carthage, sheltered by a row of promontories that protrude into the Mediterranean like a fleet straining at anchor to take sail for Rome).

The Confessions is as much a jumble of contrasts as is Apuleius’s dirty, courtly, and ecstatic tale. We try to anchor it by calling it the first Christian autobiography—even, in more heady moods, the first autobiography ever. But to call it an autobiography is a misleading half-truth. In the first nine books of the Confessions, Augustine does indeed describe his life from his birth in 354 to his conversion in Milan in 386, and the death of his mother, Monnica, at Ostia, in late 387. Only these books, accounting for slightly more than half of the text, deal with Augustine’s past life. After that—for a further 206 pages in Ruden’s translation—the great work floats triumphantly out to sea, ever further away from modern expectations of an autobiography.

In books ten and eleven, we are treated to minute self-examination and to spells of philosophical heavy lifting on the nature of memory and time. In the last two books, Augustine plunges into the shadowy, magical forest of the Hebrew Scriptures to meditate on what Moses had really meant when he described the six days of Creation.

So what is the correct reaction when we open the Confessions? It should, perhaps, be one of acute embarrassment. For we have stumbled upon a human being at a primal moment—standing in prayer before God. Having intruded on Augustine at his prayers, we are expected to find ourselves pulled into them, as we listen to a flow of words spoken, as if on the edge of an abyss, to a God on the far side—to a being, to all appearances, vertiginously separate from ourselves.

The measure of the success of Ruden’s translation is that she has managed to give as rich and as diverse a profile to the God on the far side as she does to the irrepressible and magnetically articulate Latin author who cries across the abyss to Him. Most translations of the Confessions fail to do this. We are usually left with the feeling that one character in the story has not fully come alive. We meet an ever-so-human Augustine, with whom it is easy to identify even when we most deplore him. But we meet him perched in front of an immense Baroque canvas called “God”—suitably grand, of course, suitably florid, but flat as the wall.

How does Ruden remedy this lack of life in God? She takes God in hand. She renames Him. He is not a “Lord.” That is too grand a word. Its sharpness has been blunted by pious usage. Augustine’s God was a dominus—a master. And a Roman dominus was a master of slaves. Unlike “Lord,” the Latin word dominus implied, in Augustine’s time, no distant majesty, muffled in fur and velvet. It conjured up life in the raw—life lived face to face in a Roman household, lived to the sound of the crack of the whip and punctuated by bursts of rage.

In the house of Augustine’s parents, slaves were well thrashed for gossiping. Monnica herself confronted wives whose faces bore bruises from angry husbands, with the grim reminder that, after all, their marriage contracts had handed them over to these men as so many “slaves.” One should add that brilliant recent studies of the later Roman Empire by Kyle Harper and others have left us in no doubt that slavery was alive and well in Roman Africa and elsewhere, adding a bitter taste to the social life, to the sexual morality, and to the imaginations of Romans of the age of Augustine.2 In her introduction, Ruden writes: “This imagery…may be harsh and off-putting, but a translator must govern her distaste and try to make her author’s thought and experience as vivid and sympathetic as it plainly was to his contemporaries.” To do otherwise would be “condescending, manipulative, and anachronistic.”

Advertisement

To make God more of a person, by making Him a master, does not, at first sight, make Him very nice. But at least it frees Him up. It also brings Augustine to life. In relation to God, Augustine experiences all the ups and downs of a household slave in relation to his master. He jumps to the whip. He tries out the life of a runaway. He attempts to argue back. Altogether, “Augustine’s humorously self-deprecating, submissive, but boldly hopeful portrait of himself in relation to God echoes the rogue slaves of the Roman stage.” (Indeed, the thought of the bishop of Hippo as having once been the slippery slave of God—like Zero Mostel as the plump and bouncy Pseudolus in A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum—somehow lightens the impression of a seemingly inextricable roller coaster of sin and punishment that we usually derive from reading the first part of the Confessions.)

For God can change His mood. Like any other free person, He can show a different side. The Confessions is about the marvelous emergence of new sides of God as Augustine himself changes in his relation to God, over the years, from slave to repentant son to lover. Ruden may have to defend her retranslation of the name of God from “Lord” to “Master.” But her approach is a thoughtful one. It is governed by a determination to present Augustine’s relations with his God as endowed with the full emotional weight of a confrontation between two real persons. She takes no shortcuts. Small departures from conventional translations show her constant effort to capture an unexpected dimension of tenderness (very different from that of the slave owner) in God’s relation to Augustine and in Augustine’s to God.

To take small examples: Ruden does not have Augustine “embrace” Jesus as if He were a proposition. He takes Him in his arms. When Augustine looks back at his first mystical awakening, he cries: Sero te amavi: “Late have I loved you!” It is a famous cry. But it is a little grand. You and I would say: “I took too long to fall in love.” And this—the less dramatic but more human turn of phrase—is what Ruden opts for. Repeated small acts of attention to the humble, human roots of Augustine’s imagery of his relations to God enable Ruden to convey a living sense of the Being before Whom we find him transfixed in prayer: “Silent, long-suffering and with so much mercy in your heart.”

A reviewer may add some touches to this picture. After the rude shock of meeting God as a slave master, some attention might also have been given, in Ruden’s introduction, to Augustine’s images of the tenderness of God. I think particularly of the image of the doctor and the eye salve. In the ancient world, the doctor was not the icy professional that he or she has become in the modern imagination. Unlike the surgeon, with his dreaded bag of knives, the doctor entered the house as a figure of magical, tender care. In a world with nothing like modern anesthesia, the doctor stood for the one principle of gentle change made available to bodies all too often held rigid on the rack of pain. His skilled words brought comfort, if only to the mind. His skilled hands played across the body, untying, where possible, the knots of pain. His drugs always carried with them reassuring traces of occult energies culled from herbs, which worked slowly and silently to bring the pain-wracked body back to its natural state.

As for the eye salve: the bitter mixture known as collyrium was known to everyone. Eye diseases (glaucoma and conjunctivitis) were everywhere in the dusty landscapes of the Mediterranean. The dangers to the eye of infected water were exponentially increased in every Roman city by the splendor of their public baths. Even in the bracing atmosphere of Hadrian’s Wall, 12 percent of the Roman garrison of Vindolanda (near Housesteads Roman Fort in Northumberland) were out of action, with eye infections predominating.

Hence the supreme skill with which Augustine uses medical terminology in books six and seven of the Confessions to describe the last, almost subliminal stages of his conversion. Here the crack of the whip is silent. Nor does truth dawn suddenly for him in the garish, broken-light manner of conventional conversion narratives. Instead, we enter the gentle half-light of a Roman sickroom, as God, the supremely tender doctor, tiptoes in to place his hand, at last, on Augustine’s heart:

Advertisement

My swelling settled down under your unseen medicinal hand, and the…darkened eyesight of my mind, when the stinging salve of…sufferings was applied, was healing day by day.

Ruden also might have explained even more fully the carefully constructed sense of vertigo induced by the direct encounter of two totally incommensurable beings—a storm-tossed human and an eternal God. She presents this supreme incongruity almost as an occasion for merriment. In describing Augustine’s intellectual fireworks, she stresses the element of free-floating, almost childlike intellectual play beneath the eyes of God. Here was a Being so different from us that even the most serious intellectual endeavor on our part was vaguely ludicrous.

But Augustine also uses this sense of vertigo in a different way. He has a deadly gift for miniaturizing sin. There are no large sins in the Confessions. Those that he examines most closely are tiny sins. He spends a large part of book two (nine entire pages) examining his motives for robbing a pear tree. Modern readers chafe. “Rum thing,” wrote Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes to Harold Laski in 1921, “to see a man making a mountain out of robbing a pear tree in his teens.”

But Holmes was wrong to be impatient. Only by winnowing every motive that played into that obscure act of small-town vandalism was Augustine able to isolate the very smallest, the most toxic concentrate of all—the chilling possibility that he had acted gratuitously, simply to show that he (like God, and then like Adam) could do whatever he wished. The publishers were right to put on the jacket of this book, which contains a succession of sins, each reduced to chillingly minute proportions, the image of a half-eaten pear.

The publishers would have found it much harder to illustrate the middle-aged Augustine’s notion of sex. By the time the bishop approached his sexual temptations as he wrote book ten of the Confessions in 397, they had thinned out for him so as to seem next to transparent. He had abandoned sex for a decade. Sexual scenes appeared only in his dreams. But they were there. They still spoke of forces in him that were all the more enduring for being next to imperceptible.

He speaks of these urges as a viscum—as a form of birdlime. We should note the terrible precision of this word. Birdlime is not only sticky. It is transparent. This barely visible substance would be placed at the end of a rod that would then be inserted among the boughs of a tree in such a way that the unsuspecting bird would hop without noticing from the living branch on to the adhesive surface. (In the fresco in a fourth-century bathhouse at Sidi Ghrib, nineteen miles southwest of Carthage, the owner of the villa is shown setting out for a bird hunt followed by a slave carrying a bundle of these deadly rods.) This barely perceptible, cloying glue—and not the hot pleasures of the bed, as we might expect—was what preoccupied the bishop. It might still brush against the wings of his soul, slowing, if only a little, his ascent to God.

Altogether, in reading book ten of the Confessions, we find Augustine looking at his sins as if through the diminishing end of a telescope. They are disturbing precisely because they are so very small but so very tenacious. Confronted by sensuality and violence, ancient moralists and Christian preachers had tended to deploy an “aversion therapy” based upon rhetorical exaggeration. They pulled out all the stops to denounce the shimmer of ornament, the drunken roar of the circus, the rippling bodies of dancers and wrestlers, the sight of beautiful women, and the languid seduction of perfumes. With Augustine, all this falls silent. The effect of the baleful glare of material beauty becomes no more than noting in himself a touch of sadness when he was deprived for too long of the African sun: “The queen of colors herself, this ordinary light, saturates everything we see…and sweet-talks me with the myriad ways she falls on things.”

Even the noisiest, the most colossal place of all, and the place of greatest cruelty—the Roman amphitheater—seems to shrink drastically. Augustine knew only too well what a gladiatorial show was like. He described his friend Alypius in Rome “guzzl[ing]…cruelty” as he watched the gladiatorial games. But had the cruel urge to watch gone away? No. No longer does Augustine follow the venationes, the matador-like combats of skilled huntsmen armed with pikes and nets against lithe and savage beasts that had replaced gladiatorial shows all over Africa:

[But] what about the frequent times when I’m sitting at home, and a lizard catching flies, or a spider entwining in her net the flies falling into it, engrosses me? Just because these are tiny animals doesn’t mean that the same predation isn’t going on within me, does it?

For Augustine, this is no idle lapse of attention. It is a realization of continued urges that is as disturbing as the thin voice of a ghost in a lonely room: “You see, I am still here.”

But despite the eerie hiss of sin, Augustine also remembers that he had tasted a little of the sweetness of God:

And sometimes you allow me to enter into an emotion deep inside that’s most unusual, to the point of a mysterious sweetness, and if this is made whole in me, it will be something this life can’t ever be.

And what is more, he remembered that he had once tasted this sweetness in company. The astonishing (and little-noticed) fact about the much-debated vision of Ostia, which occurred on the eve of Monnica’s death in 387 and offered a view of “what the eternal life to come would be like,” was that Augustine had experienced it along with his mother: “We conversed together alone, very gently,” and the vision had come to them both.

At the end of time, a vast company of humans and of angels would share forever the same vision that Monnica and Augustine had shared, if only for a fleeting moment. And they would do it all together. That is the whole point of the last, triumphant book of the Confessions: for, up above the heavens, “they always see Your face…and they lose themselves in love for it.”

Meanwhile, there was a church to run. A body of hitherto unknown letters written by Augustine in his old age, discovered and published by the Austrian scholar Johannes Divjak in 1981, has been much discussed and used by scholars, but has yet to receive its due weight in our general image of Augustine. Pundits ourselves and the students of pundits, we like to think of our heroes and heroines in an elevated light. We expect the author of a Great Book such as the Confessions to remain in his study—lucubrating darkly, for good or ill, on weighty topics such as sex, subjectivity, and the self.

It should come as a salutary surprise to learn, from Letter 10 of the Divjak collection, that in 428 AD—thirty years after the writing of the Confessions, that is, and maybe only two years before his death—Augustine, now seventy-four, was deeply engaged in an attempt to block the slave trade out of the port of Hippo. Sent inland by slave traders, gangs of slavers had scoured the isolated hamlets in the mountains behind Hippo, shipping cargoes of terrified peasants across the sea. They may have sold them to landowners in Italy and Gaul who were anxious to restock their estates after the disruption caused by the barbarian invasions earlier in the century.

Augustine reported the affair to his old friend Alypius, who was in Rome once again—no longer to watch the games, but to search the libraries of the city for copies of imperial laws that might be used to put an end to this “evil of Africa.” The church of Hippo had already ransomed 130 of these captives. Well lawyered-up, the slave traders had responded by suing Augustine for theft of their property. Ever conscientious and on his guard to make a watertight case, Augustine noted for Alypius the testimony of those rescued by the church:

Once when I was with some of those who had been freed from their wretched captivity by our church, I asked a young girl how she had come to be sold to the slave dealer. She said she had been taken from her parents’ home…she said that it was done in the presence of her parents and brothers. One of her brothers…was present [while Augustine spoke to the girl] and, because she was little [and may well have known no Latin: the hinterland of Hippo was still Punic-speaking],…he revealed to us how it had been done. He said that thugs like these break in at night. The more they are able to disguise themselves, the less likely the victims are to resist: since they think they are a barbarian band. But if there were not traders such as these [back on the docks of Hippo] things like this would not happen.

For Augustine, service to the church had come to include such humanitarian work, among so many other things. But it also continued to mean the attempt to find, somewhere in this world—in common prayer, in the collective singing of the Psalms, in the high drama of saints’ feasts, and in the gathering for the Eucharist—some place for the shared sweetness of God. A few years before his intervention in the slave trade at Hippo, Augustine concluded one of his sermons on the Gospel of John:

I sense your feelings of yearning, of eagerness, being lifted up with me to what is above…. But now I will put away the copy of the Gospel. You are all going to depart as well, each to your own home. It has been good, sharing the Light together, good rejoicing in it, good exulting in it together; but when we depart from each other, let us not depart from Him.

It is good to be reminded of such a man by a translation of his masterwork that does justice both to him and to his God.

This Issue

October 26, 2017

Rushdie’s New York Bubble

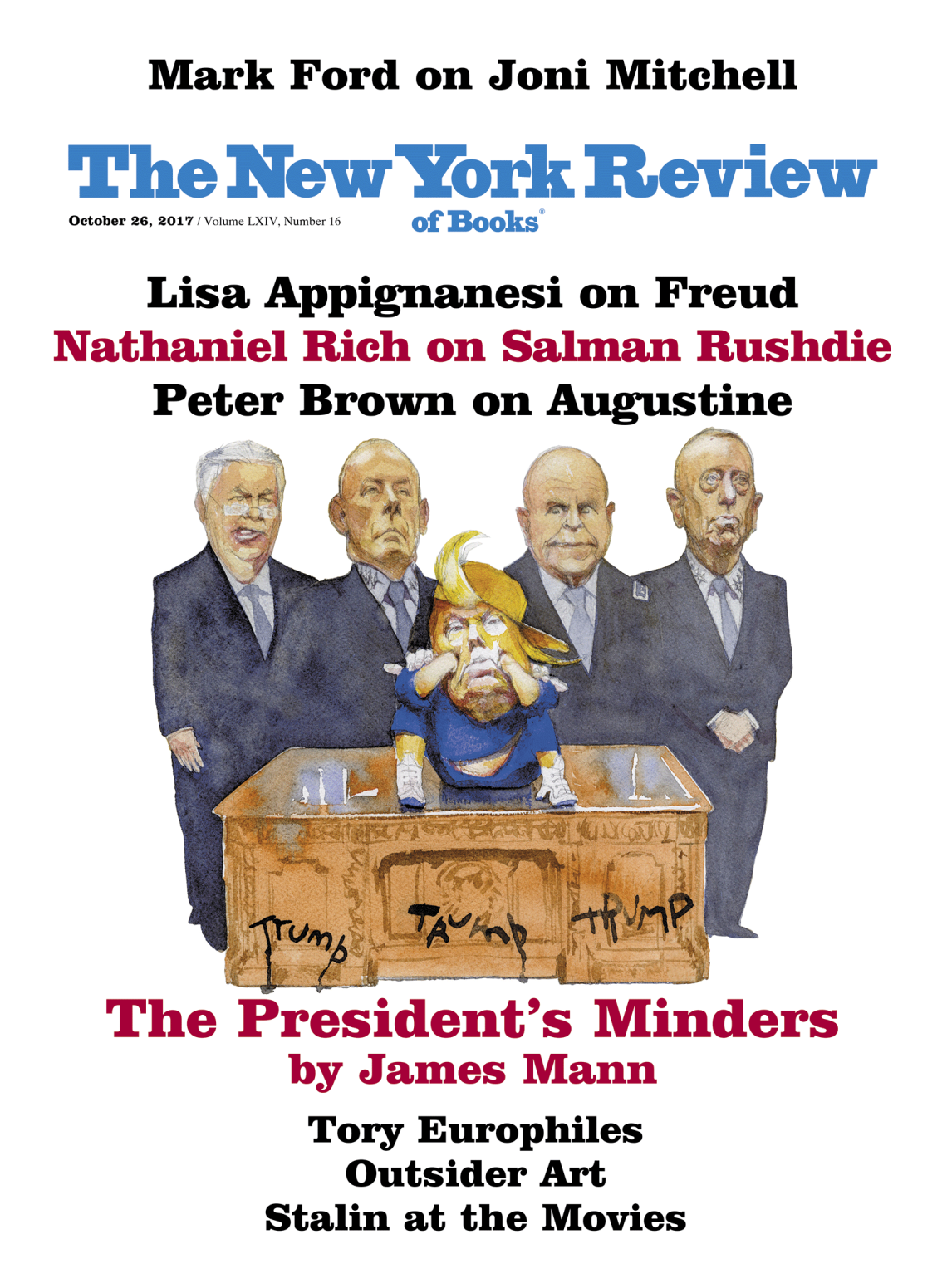

The Adults in the Room

-

1

The Golden Ass, translated by Sarah Ruden (Yale University Press, 2012), reviewed in these pages by G.W. Bowersock, December 20, 2012. ↩

-

2

Kyle Harper, Slavery in the Late Roman World, AD 275–425 (Cambridge University Press, 2011) and From Shame to Sin: The Christian Transformation of Sexual Morality in Late Antiquity (Harvard University Press, 2013); see my review of the latter in these pages, December 19, 2013, and Brent D. Shaw, “The Family in Late Antiquity: The Experience of Augustine,” Past & Present, Vol. 115, No. 1 (May 1987). ↩