1.

Long focused on the impact of live theater, Stalin did not immediately grasp the full power of film. But the producer Boris Shumyatsky persisted, and goaded the Party to issue a directive to film all major events in the USSR, design handheld cameras to be put into wide production, and have regional officials treat newsreels the way they treated the press. Stalin began to review the newsreels at Kremlin cinema sessions. But it had really been his previewing of the 1934 film Chapayev that transformed him—a person accustomed to working with written texts—from someone who occasionally viewed films for diversion to their executive producer, overseeing everything from the backgrounds of scenes to the dialogue and score.

The dictator played a decisive part in supporting not just subjects of political import but also farce. In that regard, an enormous breakthrough was wrought by a young assistant to the virtuoso Sergei Eisenstein, after the latter’s scandalous failure to finish a film in Mexico. Shumyatsky had suggested that Eisenstein next make a Soviet comedy, but the director showed little interest. His assistant, Grigory Alexandrov, using every Hollywood trick he had learned in their travels to Los Angeles, then cowrote and directed Jolly Fellows, which became a smash hit.

Stalin’s inner circle had divided over the appropriateness of comedy. When Shumyatsky was set to premiere Jolly Fellows in the Kremlin, Kliment Voroshilov, who had seen it, stated, “It’s an interesting, jolly, thoroughly musical film featuring Utyosov and his jazz.” Lazar Kaganovich objected that the musician Leonid Utyosov had no voice; Andrei Zhdanov complained that Utyosov was a master only of criminal underworld songs. “You’ll see,” Voroshilov countered, “he’s a very gifted actor, an extraordinary humorist, and sings delightfully in the film.” He was right. “Brilliantly conceived,” Stalin said to Voroshilov after viewing one scene with a jazz orchestra rehearsal that devolves into a hilarious fight, and another with collective farm livestock run amok.

The film allows you to relax in an interesting, entertaining fashion. We experienced the exact feeling one has after a day off. It’s the first time I have experienced such a feeling from viewing our films, among which have been very good ones.

After watching another film, Stalin returned to discussion of Jolly Fellows, lauding the bold acting of the female lead, Lyubov Orlova, and male lead, Utyosov, as well as the excellent jazz. “He talked about the songs,” Shumyatsky wrote. “Turning to comrade Voroshilov, he pointed out that the march would go to the masses, and began to recall the melody and ask about the words.”

A new genre, the Soviet musical comedy, was born. Shumyatsky’s determination had paid off. He had witnessed a live performance of Utyosov’s band—whose musicians sang, danced, and acted—and had suggested they team up with the director Alexandrov. Utyosov, for his part, had insisted on music by Isaac Dunayevsky, a graduate of the Kharkov Conservatory who had made a name for himself at the Moscow Satire Theater and more recently the Leningrad Music Hall. Vasily Lebedev-Kumach, the son of a Moscow cobbler and himself a writer at the satirical periodical Crocodile, composed the lyrics.

When ideologues attacked the resulting work, Shumyatsky galvanized Stalin’s support. Jolly Fellows had gone into final editing, following the dictator’s suggestions, but its opening was delayed by Sergei Kirov’s assassination. It premiered publicly on December 25, at Moscow’s Shock Worker cinema, where Orlova, Utyosov, and Alexandrov were in the audience. A banquet followed at the Metropole. General release took place in January 1935, and soon an astonishing six thousand copies of the film were in circulation throughout the country.

The publicity campaign, unprecedented for the Soviet Union, borrowed American techniques, with postcards of scenes from the film and phonographic records of the songs. Shumyatsky even had sheet music of the score published with an attractive cover, and there were tie-in cookies from the baking trust and cigarettes from the tobacco trust. The film’s stars featured in radio appearances.

Many cultural figures collaborated with the Soviet party-state precisely for its wherewithal to deliver mass audiences. To be sure, whereas listeners in Britain or Germany could tune in to several stations, including some that originated from abroad, the Soviets invested in cable (wire) radio, which was inexpensive and durable, enabling mass production, and imposed far stricter state control over content, since the wires delivered just the two official stations. Only the privileged few had hard-to-procure wireless receivers with tuners. Wire radios were installed in outdoor public spaces, factories, meeting halls, clubs, and dormitories. The Soviet Union had 2.5 million radio reception points already by 1934. Radio Moscow and Radio Comintern were broadcasting approximately eighteen hours per day, creating an ambient Sovietness.

“Boring agitation is counter- agitation,” one Soviet film critic argued. Surveys of radio listeners’ letters showed that they wanted fewer symphonies and more humor, information about the outside world, advice on child-rearing, medical issues, and other daily life concerns, and entertainment, such as folk music, Gypsy romances, jazz, operettas (not operas), and songs from the latest films. While Germany had Marlene Dietrich and America Greta Garbo, the Soviets had Orlova, promoted in the press, books, and fan postcards. (She and Alexandrov would begin a love affair and later marry.) The songs proved to be easily and widely memorized. From streets to shop floors, almost the entire USSR was singing “Such a Lot of Nice Girls” (or the tango version, “Heart,” released by Pyotr Leshchenko) and the march “A Happy Song Lightens Your Heart.” Even in profoundly anti-Soviet Poland Jolly Fellows would find popularity. The comic master Charlie Chaplin would praise the film as better propaganda for the Soviet cause than executions.

Advertisement

Stalin authorized an all-Union Creative Conference of Workers in Soviet Cinema (January 8–13, 1935), albeit without formation of a formal union such as the writers had. Eisenstein was awarded the task of delivering the keynote. “When I heard Eisenstein’s report, I was afraid that he knows so much, and his head is so clear that, it is obvious, he’ll never make another film,” the director Oleksandr Dovzhenko said in his follow-up speech. “If I knew as much as he does, I would literally die. (Laughter, applause.)” Pravda published a congratulatory note from Stalin to Shumyatsky: “Greetings and best wishes to the workers of Soviet cinema on the day of its glorious fifteenth anniversary.”

Soviet power expects from you new successes—new films that, like Chapayev, proclaim the greatness of the historic cause of the struggle for power of the workers and peasants of the Soviet Union, mobilize for the attainment of new tasks, and remind us of both the achievements and difficulties of socialist construction.

That same day, Stalin attended the ceremony at the Bolshoi where, for the first time, state awards were handed out to film workers. He had edited the proposed awards list: Orders of Lenin were given to the Leningrad Film Studio, Shumyatsky, Pavel Tager (who had helped introduce sound to Soviet films), and numerous directors. Eisenstein had been proposed for the lesser Order of the Red Banner, which Stalin crossed out, substituting something lesser still: “honored artist.” After this humiliation, Eisenstein had to offer the closing remarks. “No one here has had to listen to so many compliments about highbrow wisdom as I,” he stated. “The crux—and this you know—is that I have not been engaged in film production for several years, and I consider the [awards] decision a signal from the party and government that I must enter production.” The gathering concluded with a performance of the third act of Swan Lake.

Shumyatsky did not speak at the ceremony or at the conference, but Pravda published an excerpt from his forthcoming book, Cinema for the Millions. “The victorious class wants to laugh with joy,” he wrote. “That is its right, and Soviet cinema must provide its audiences with this joyful Soviet laughter.” He admitted, however, that “we have no common view on such fundamental and decisive problems of our art as the interrelationship between form and content, as plot, as the pace and rhythm of a film, the role of the script, the techniques of cinema.” In fact, all he and other film people had to go on was Stalin’s utterances or their own intuition about what might please him.

2.

Secret police, in their smartest dress uniforms, lined the walls of the cavernous main hall and all the entrances of the Grand Kremlin Palace for the 1939 New Year’s banquet. Soviet officials did not bring their wives unless the latter, too, held official positions, such as Vyacheslav Molotov’s wife Polina Zhemchuzhina (fishing industry commissar). But much of the beau monde was intermarried: the actor Ivan Moskvin attended with his wife, Alla Tarasova, a star of the same theater; the filmmaker Grigory Alexandrov with his wife, the singer-starlet Lyubov Orlova; the dancer Igor Moiseyev with his common-law wife, the Bolshoi prima ballerina Nina Podgoretskaya.

But Stalin himself could come off as the movie star: the mischievous grin, the lifted head, the pauses, nods, glances. During the toasts, when he called out Soviet triumphs and heroes, people clinked glasses, tapped knives and forks, and shouted his name. By the time the USSR State Jazz Band entered the anteroom of the Andreyev Hall, it was after 2:00 AM. A Chekist, as the police liked to be called, summoned them to the stage following the Alexandrov Red Army Ensemble—240 singers and dancers—and Igor Moiseyev’s State Folk Dance Ensemble.

“We walked into the dimly lit, deserted Andreyev Hall, which is used by the Supreme Soviet for its meetings,” recalled Juri Jelagin, a violinist. “The hall was lined with rows of armchairs like a theater auditorium, or perhaps more like a university auditorium, because each chair was equipped with a small writing desk and a radio headset.” They reached a door, behind which was a stage. “The bright lights blinded us. We were in the ornate, white [St. George’s] Hall of the Kremlin…. The large tables were crowded with people, and a regular feast was in progress.” In front of the stage, at a distance from the other tables, was the Presidium table, the seats facing the hall, backs to the performers.

Advertisement

When the jazz musicians appeared on the stage, Stalin and his entourage turned and applauded. “Stalin was wearing a khaki tunic without any ribbons or decorations. He smiled at us and nodded encouragement. In front of him stood a half-empty glass of brandy.” The jazzmen, with their female vocalist, Nina Donskaya, performed “Jewish Rhapsody,” by Svyatoslav Knushevitsky, perhaps Moscow’s top cellist. (He was married to Natalya Spiller, the Bolshoi soprano much admired by Stalin.) For whatever reason, according to Jelagin, Stalin paid no attention to Donskaya. “He turned away and began to eat.”

The mass murderer was able to differentiate, within his conventional tastes, a sublime performance from a merely good one. He loved opera, and selections were invariably included from the prerevolutionary repertoire (Rimsky-Korsakov, Glinka, Mussorgsky, Borodin, Tchaikovsky) and the better-known Western classics (Carmen, Faust, and Aida). But his greatest passion was for Russian, Ukrainian, and Georgian folk songs. After the jazz band had concluded its six approved numbers—among them Tchaikovsky’s “Sentimental Waltz” and Stalin’s sentimental favorite, “Suliko”—the Presidium table, according to Jelagin, “applauded long and vigorously.”

Only now, after exiting and storing their instruments, were the musicians invited to dine—in a separate hall for performers, one floor below, at tables loaded with “caviar, hams, salads, fish, fresh vegetables [in winter], decanters of vodka, red and white wine, and fine Armenian brandy. There were about four hundred of us, but the tables could seat at least a thousand.” Here, the Chekist servers wore their police uniforms. The musicians were addressed by the latest chairman of the committee on artistic affairs, Alexei Nazarov, who toasted Stalin as well as some of the most famous performers, such as the singer Ivan Kozlovsky.

Kozlovsky, the virtuoso soloist at the Bolshoi, would receive the Order of Lenin in 1939. (The next year, Stalin would make him a USSR People’s Artist.) He possessed a transparent, even voice, with a beautiful and gentle timbre in the upper register; it was not particularly powerful yet filled the largest spaces. He hailed from a Ukrainian village and had a brother who had emigrated at the end of the civil war and wound up in the United States, which alone would have been enough to doom the tenor. Zealous Chekists went to Kozlovsky’s native village to dig up dirt, but when Poskryobyshev handed Stalin thick files of compromising material, the despot was said to have observed, “Fine, we’ll imprison comrade Kozlovsky—and who’ll sing, you?”

Whether the story is apocryphal or not, the despot was said to keep track of the schedule for the Bolshoi and to terminate meetings in the Little Corner to catch an aria sung by Kozlovsky, Maxim Mikhailov (a bass) or Mark Reizen (also a bass), the lyrical tenor Sergei Lemeshev, the lyrical sopranos Spiller and Yelena Kruglikova, or the mezzo-soprano Vera Davydova. At the New Year’s gala, Kozlovsky, who acquired the reputation of being an unbearable person, sang “La donna è mobile,” from Rigoletto, at Stalin’s request.

Two days later, Stalin informed USSR Procurator General Andrei Vyshinsky that he wanted a public trial of those arrested in the NKVD. “The enemies of the people who penetrated the organs of the NKVD,” the commission on the secret police internally reported to Stalin—as if the secret police rampage had somehow occurred without his directives—

consciously distorted the punitive policy of Soviet power, conducting a mass of baseless arrests of people guilty of nothing, and at the same time protecting the activities of enemies of the people…. They urged that prisoners offer testimony about their supposed espionage activity for foreign intelligence, explaining that such invented testimony was necessary for the party and the government in order to discredit foreign states.

The despot circulated the report to the inner circle: they needed to know how to interpret the terror, as the result of the infiltration of “spies in literally every [NKVD] department.” But for whatever reason, a public trial of the NKVD never took place. “I am very busy with work,” Stalin wrote on January 6, 1939, to Alexander Afinogenov, a reprieved writer, who had sent in a copy of his latest play to read. “I beg forgiveness.”

Lavrentiy Beria, the chief of the NKVD, issued a secret directive calling for NKVD branches to cease recruiting informants for surveillance of Party and factory bosses, and to destroy, in their presence, the files compiled against them. Provincial Party bosses were even invited to scrutinize the dossiers of all NKVD personnel in their domains. But Stalin had some second thoughts. “The Central Committee has learned,” he wrote in a telegram to all locales on January 10, 1939, “that the secretaries of provinces and territories, checking on the work of the local NKVD, have charged them with using physical means of interrogation against those arrested as if it were a crime.” He informed them that the “physical methods” had been approved by “the Central Committee” and agreed to by “the Communist parties of all the republics” (whose leaders had almost all been shot as foreign agents and wreckers). “It is known that all bourgeois intelligence services apply physical coercion with regard to representatives of the socialist proletariat, and in the ugliest forms,” he stressed. “One might ask why the socialist intelligence service must be more humane with regard to inveterate agents of the bourgeoisie.”

This Issue

October 26, 2017

Rushdie’s New York Bubble

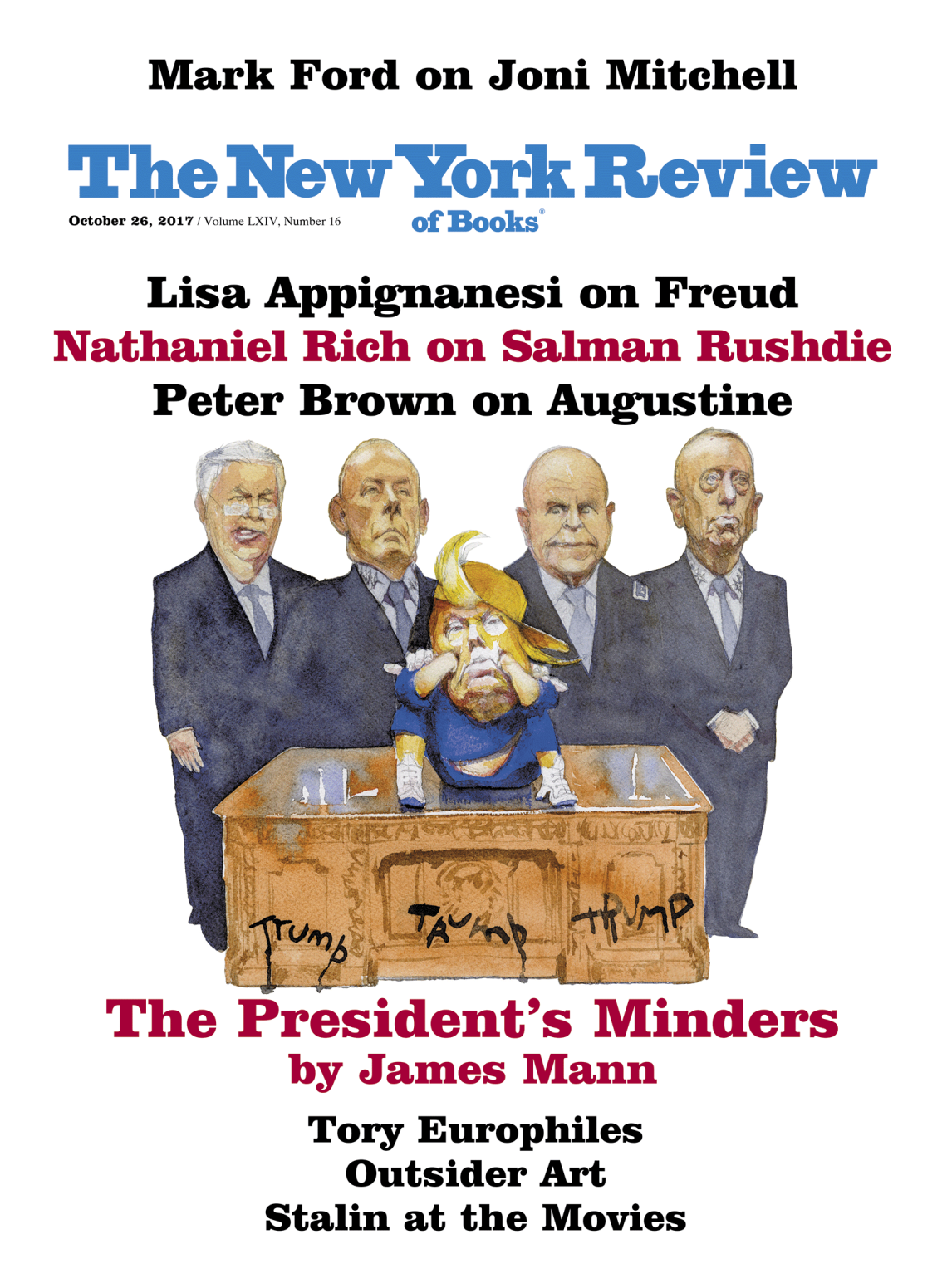

The Adults in the Room

Dialogue With God