Alexander Calder—Sandy to all who knew him—was deceptively easygoing: a bulky, lumbering, slow-spoken figure with big, capable hands and a sleepy smile. Poise, balance, and equilibrium were his priorities, and he could be ruthless in their pursuit. You get some idea of his disruptive potential from the strict rules laid down by Pierre Matisse before he agreed to mount a first show of Calder’s elegant, austere abstractions in his New York gallery: “There won’t be any wall cracking or floor nailing, or ceiling bursting and I have to be sure that my carpet is not going to be eated [sic] up by your wild menagerie.”

Sandy was the third Alexander Calder, son and grandson of émigré sculptors, stern Scottish forebears apparently descended from a tombstone-cutter in the granite city of Aberdeen. His Calder grandfather made the massive bronze statue of William Penn that presides high above Philadelphia on top of the dome of City Hall. His grandmother (who came from Glasgow) said that each of her six sons was the result of rape. One of them was Sandy’s father, Alexander Stirling Calder, who married a painter called Nanette Lederer, a secular Jew, which made their two children technically Jewish. Sandy and his elder sister posed for their portraits at home in stone and on canvas from infancy, “bewitched,” as Jed Perl quaintly puts it, “drawn into art’s magic circle from which neither of them ever strayed.”

Sandy started off as he meant to go on, energetic and experimental. At the age of seven he was catching horned toads and racing them, harnessed to matchbox chariots. A year or two later he made himself a suit of armor—shield, breastplate, sword, lance, and helmet—so he could ride out as Sir Tristram, one of King Arthur’s Knights of the Round Table. At nine he got his first set of tools and a workshop of his own in the cellar. A self-portrait in crayon from around about this time shows him at work with fretsaw, drill, hammer, and pliers. “I was never satisfied with them,” he said of his toys. “I always embellished and expanded their repertoire with additions made of steel wire, copper, and other materials.”

His movements were as clumsy as his fingers were skillful. He was the kind of boy who couldn’t catch a ball but had no problem drawing a perfect curve. A Dog and a Duck, cut with shears from a brass sheet when he was nine or ten, show an impressive degree of stylized sophistication. As a teenager he criss-crossed his bedroom with strings for opening the window, switching the lights on and off, pulling up or lowering the shades. On cleaning day, “a stormy scene always followed Sandy’s return from school,” said his sister: “a crucial bit of string had been removed from his doorknob, or wire from the chair. Mother sympathized, but felt obliged to maintain a minimum of domestic order.”

He was fifteen when his father got a job in San Francisco, overseeing the production of sculpture in bulk for an international exposition to celebrate the opening of the Panama Canal in 1915. Forty-four sculptors posted off miniature models of their work to be enlarged and manufactured in Stirling Calder’s workshop. He himself produced ninety casts of a mighty iron maiden, wearing a star on her head and balancing barefoot on a ball, to be set up as his trademark all over the exposition. Other prodigies symbolizing America’s view of its future included a giant telephone, a typewriter so big it weighed fourteen tons, and Stirling’s own Fountain of Energy, “an allegorical lollapalooza” in the shape of a colossal horseman surmounting the globe attended by Fame and Glory, one on each shoulder, represented as little fairy figures on tiptoe with wings spread as if about to take off.

Sandy, always more practical as well as more imaginative than his father, made a wire fork with a trigger ejector for exterminating slugs. What fascinated him more than almost anything else at the Panama-Pacific exposition was the pointing machine, used to scale up the forty-four small maquettes into monumental statues by means of parallel needles and two turntables rotating through sprockets and a bicycle chain. Two years later the young Calder enrolled in a college of technology to study engineering. Although he came later to feel that his training as an engineer had proved a dead end, it made him alert to invisible physical forces and adept at manipulating them in ways beyond the reach of most artists.

After graduation he drifted through a series of odd jobs and short-term assignments, finally enrolling at New York’s Art Students League, where he supported himself more or less by producing sketches for various journals, becoming a regular contributor to the National Police Gazette. Much of his time was spent drawing and painting the life of Manhattan: building sites, city traffic, excavations, prize fights, people on the sidewalk or in Central Park. Spools of wire crammed his pockets on these expeditions, along with pliers, hammer, and nails, all as essential to him as his tubes of paint. He stuck it out as an art student for just over a year before following the standard career path for any ambitious young American painter or writer and sailing for Paris in July 1926.

Advertisement

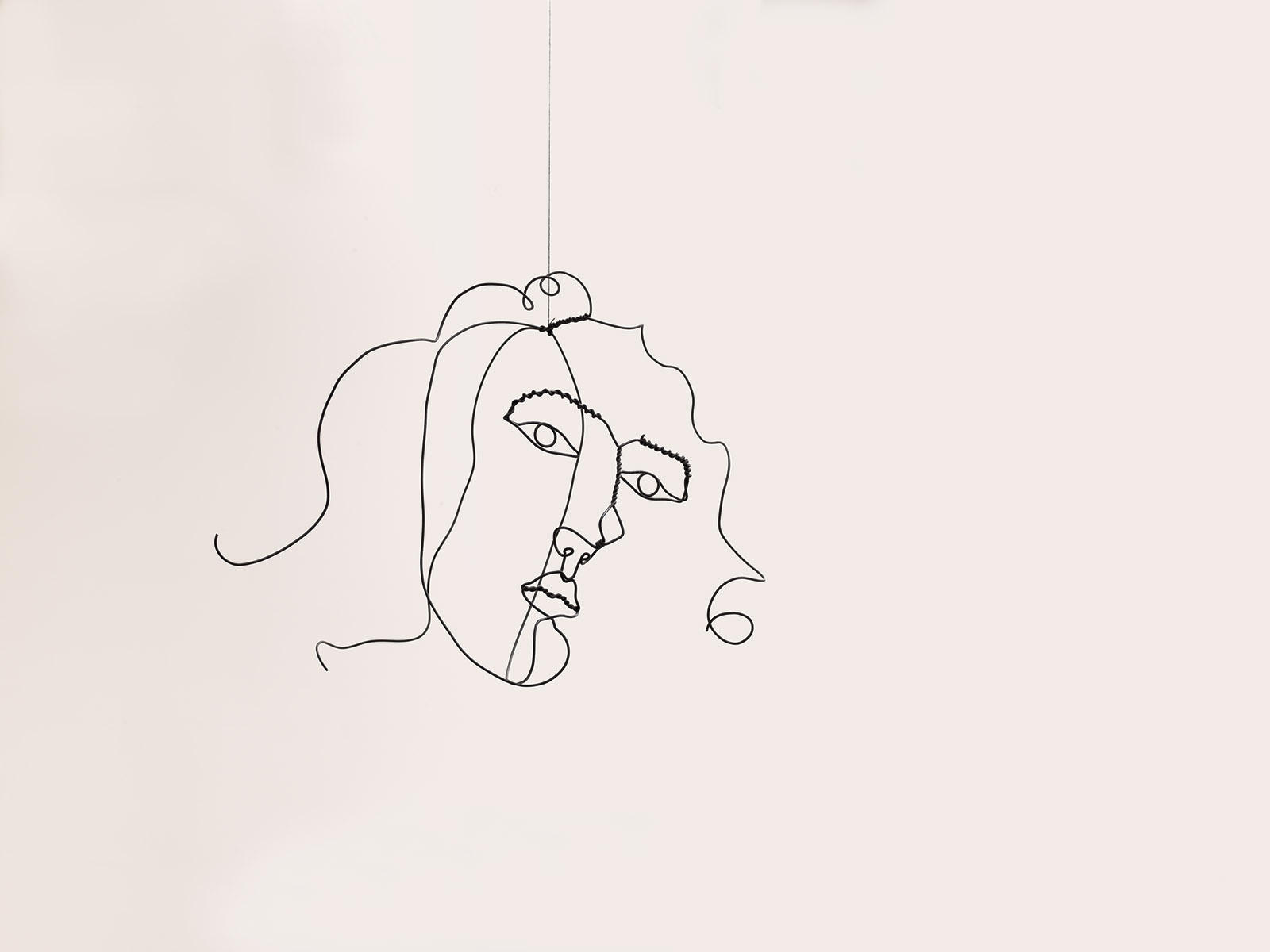

Sandy took with him a specially made suit of bright-yellow striped tweed designed to make him stand out on the streets of Montparnasse, though it must have been cruelly hot in the broiling temperatures of a Parisian summer. He tried one or two art schools without enthusiasm, but Paris—or the freedom it gave him, and the proximity of other artists of the same caliber—released something in him. From then on he turned back increasingly to his childhood medium of wire, bending, twisting, and shaping it to dash off lightning sketches with a cartoonist’s concision and power: humorous, observant, expressive wire figures suggesting, as Perl puts it, “rapidly executed line drawings leaping into the third dimension.” One of the few to survive from his first months in Paris is a masterly portrait of the dancer Josephine Baker, whose raucous grace and nerve Calder laconically translates into loops, lines, and coils: “Baker’s spiralling breasts and belly and curlicue private parts define a new kind of rococo comedy.”

Over the next three or four years he made a series of absurd, astute caricature heads of young movers and shakers on either side of the Atlantic: the comedian Jimmy Durante, the dealer and curator Carl Zigrosser, the painter Marion Greenwood, and the ubiquitous Kiki de Montparnasse. Parisians nicknamed Calder “the Wire Man,” although, as Kiki said, “there was nothing wiry about his build. The artist…resembles a lumberjack in his striped sweater, corduroys and heavy shoes.” A burly man in mustard-colored sweaters, orange socks, and eye-catching tweeds, riding a bicycle with wire horses and wooden cows crammed into the basket or slung from the handlebars, Calder at this point produced much the same effect in life as in his work: a one-off American cross between the French Surrealists and cranky English humorists like Edward Lear or William Heath Robinson.

What seems to have clarified his intentions and focused his mind was his Circus, a disconcerting work-in- progress that preoccupied him from his first days in France. He gave performances in his hotel room or in friends’ houses, squatting on the ground with a tiny circus ring marked out beside him. Small jerky dogs jumped through hoops. Pint-sized people shot from catapults onto horses’ backs. There were clowns, and a bearded lady, and trapeze artists who leapt and swung in elaborate aerial duets. Audiences watching the Cirque Calder found it impossible to classify or explain. Clearly it was neither a toy nor a puppet show, and certainly not a conjuring trick, although everyone who saw it agreed its impact was magical.

Word spread around Paris. Jean Cocteau dropped in on a performance (Calder disliked him on sight), and Isamu Noguchi worked the record player. When Calder visited England a few years later, the London avant-garde art world, headed by Ben Nicholson and Barbara Hepworth, sat on the floor in the Mall Studios with mugs of beer in their hands to watch him manipulate “his marvelous little creatures made of wire, wood and rag. They seemed incredibly alive as they pranced, pirouetted and clowned, more real than the real tinsel thing. It was enchanting.”

The Circus, probably the best known of all Calder’s works, evolved over many years alongside his characteristically loopy, lolloping animals—Goldfish Bowl, Copulating Pigs—and figures like the Trick Cyclist, and the Shot-Putter (“all the sculpture’s considerable impact centered on the reach of the arm, the tiny waist and the shot-putter’s strong legs”). These wire pieces were mostly around a foot high, but some—Hercules and Lion, for instance, and the famous Brass Family—were up to five times as big. The lanky figure of Spring is almost eight feet tall. Elements of risk and danger, and the improvisation involved in performance art, evidently suited Calder. On a brief return to America he was invited in January 1930 to exhibit with Harvard’s Contemporary Art Society by Lincoln Kirstein, then an enterprising undergraduate who was taken aback when his guest turned up at the railroad station with his standard baggage of wire and pliers, plus a good many wood blocks, but no paintings or sculpture. Back at the dorm,

Advertisement

Sandy took off his shoes and socks and changed into pajama bottoms. Using a big toe as anchor, he bent, turned, and twisted his seventeen promised pieces, each affixed to its wooden base. There was a quivering Hostess with her shaky lorgnette; a cow with four spring udders and a coil on the floor representing “cow pie.”

There had always been humor in pieces like the portrait of Carl Zigrosser with his comical piecrust hairline, button chin, and “wide fruit-slice-shaped smile,” or the head of Edgar Varèse made from what looks like a single length of wire outlining with minimalist economy the composer’s receding hairline, grizzled eyebrows, and baggy pouches under his eyes. These wire portraits seem to have functioned as a kind of transitional activity before, during, and after his shift to pure abstraction, precipitated by the shock of Calder’s first visit to Piet Mondrian’s studio in Montparnasse in October 1930. He was galvanized by Mondrian’s strange, bare, white-painted interior—full of empty space, bright light, and straight lines—and by his even stranger paintings, composed on a white ground from square and rectangular blocks of pure color outlined or contained within thick black lines. When Calder, apparently thinking in terms of works he hadn’t yet invented, suggested making the rectangles oscillate, Mondrian replied sternly that there was no need: “my painting is already very fast.”

Calder felt as if he’d been hit, “like the baby being slapped to make his lungs start working.” For a long time he had, in Perl’s words, been “backing his way into modernism.” The Circus, initially intended perhaps to deflate or sidestep the derisive incomprehension that greeted so much contemporary art at the time, played a crucial part in this realignment. What Perl calls its “mobile calligraphy” was at the core of the exhibition Calder held in Paris a year after he met Mondrian, at which he showed pieces stripped of all extraneous detail, designed to explore the tensions controlling lines and shapes suspended in space. Fernand Léger wrote in the catalog: “Looking at these new works—transparent, objective, exact—I think of Satie, Mondrian, Marcel Duchamp, Brancusi, Arp—these unchallenged masters of unexpressed and silent beauty. Calder is of the same line. He is 100 percent American.”

The show’s first visitor, even before the doors officially opened, was Picasso. For his next exhibition a year later, Calder fitted motors, gears, and belt drives to his pieces to make them move (a mechanical experiment almost immediately abandoned in favor of natural motion powered by currents of air). When he asked Duchamp what to call them, the answer was “mobiles.” Abstraction remained virtually unheard-of in Paris, but the show was an immediate sensation. Already these works have a purity and simplicity that mark them as unmistakeably Calderian. His mobiles, and later his stabiles, correspond to some kind of basic need easier to grasp than to articulate. When he first showed them in New York, a baffled reporter queried the point of a piece called Two Spheres. “This has no utility and no meaning,” Calder said, giving the best and most succinct definition of abstract art that I’ve ever heard. “It is simply beautiful. It has a great emotional effect if you understand it. Of course if it meant anything it would be easier to understand, but it would not be worthwhile.”

In 1933, impelled by an increasingly sinister atmosphere as political, social, and economic unrest spread across Europe, Calder left Paris to settle permanently in the US. He was married by this time to a girl he met on one of many transatlantic crossings, Louisa James, a great-niece of the novelist Henry James, who would surely have approved of the match. Along with many others in Montparnasse, the Calders had come to feel “that modernism could be reimagined in Manhattan. What nobody could as yet imagine was how many…creative spirits…would be forced in the next few years…to re-invent themselves in New York.”

The couple found a semi-derelict farmhouse in Roxbury, Connecticut, and set about restoring it. Calder’s horizons expanded as if America lifted an internal block or restriction. Perl sees his response as the impact on an essentially urban imagination of the great spaces and high wide skies of New England. The summer after the move Calder commandeered an old icehouse for his studio and made Steel Fish, a gigantic composition of curving shapes, straight lines, and angles suspended from a single slender upright. Set on a hilltop, outlined against the sky, as responsive to the slightest breeze as to tearing winds, Steel Fish embodies the energetic change of perspective that American artists brought to the European tradition. Calder had eliminated almost everything from his work except the boldness and openness already implicit in Josephine Baker. The potency of this new piece comes less from its scale—Steel Fish is just under ten feet tall and broader than it is high—than from the exhilarating precision of its strict linear geometry. “There’s something rawboned, loose-limbed, frank, and unrestrained about Steel Fish,” writes Perl, pinning down the quality that makes it quintessentially American.

The Roxbury house filled up with friends and fellow artists. Two daughters were born in the next few years. The more ascetic Calder’s work became, the more flamboyant his feats as a handyman. He brought the same exuberance to everything he made, from his soap dish, toilet roll holder, and the machine for tickling his wife in the next room to a wild profusion of kitchen gadgets, grids, grills, spatulas, strainers, slicers, and skimmers. He manned the boiler and drove the car. The style of the hospitable household is nicely conveyed by Saul Steinberg’s drawing of Calder and his younger daughter Mary seated in the family’s ancient open-topped touring limo with some sort of ship’s rigging mounted above it and countless objects dangling below: horns, lamps, hooters, sprinklers, knobs, cogs, contraptions of every sort with wire festooned all over them.

Calder started showing his work at this point at Pierre Matisse’s increasingly prestigious gallery in New York. It was a prickly relationship, evenly matched on both sides: “two wily egotists engaged in a genial battle,” writes Perl. “Calder was the bull in the china shop. But it was Matisse’s shop.” However infuriating Calder’s rumbustiousness, his terrible puns, and his irrepressible earthiness, his work had a magnetic force Matisse could not withstand. He set aside his misgivings, as purists commonly did on both sides of the Atlantic. Virgil Thomson described much the same process when Calder designed strange moving scenery for a production of Erik Satie’s symphonic drama Socrate, based on the dialogues of Plato. The decor seduced audiences in spite of themselves, “so majestic was the slowness of the moving, so simple were the forms, so plain their meaning.”

If the French saw Calder as entirely American, his compatriots found him indefinably French, and he was one of very few artists who have managed to capitalize on a dual allegiance instead of being marginalized by it in both countries. Although his grasp of the language always remained rudimentary, by the time he left France Calder had become, according to Perl, the only American to be accepted on equal terms by artists of his radically innovative generation in Paris.

Calder: The Conquest of Time is an immensely erudite work, meticulously thorough, painstakingly researched, and lavishly illustrated. Its grasp of detail and breadth of knowledge, especially of the American art scene, would be hard to match, but even the most conscientious catalogue raisonné does not make a biography. When it comes to the emotional, imaginative, and psychological complexities that are the biographer’s province, Perl seems altogether more cursory, too often dismissing them out of hand with a rhetorical question: “What were the origins of Calder’s originality?” “Was Calder a mama’s boy?” “Was Calder actually in love with anyone before he met…the woman who would become his wife, in 1929?” “Was Sandy Calder open-minded?” “Who can doubt that this snippet of poetic fun was also a cry for help?”

Perl’s response to the incessant questions he asks himself is always a variant on the same theme: “There is no way to know.” But the purpose of biography is precisely to address this kind of concern. Perl is too scrupulous a historian and too good a writer with too sharp an eye to be perpetually dodging issues central to his subject’s life. He makes little or no attempt to characterize Louisa Calder, who, once married, becomes a cipher solely intent on furthering her husband’s intentions, endorsing his beliefs, and bolstering his career. For all his brilliance and scrupulosity, Perl has curious lapses into superficiality, his evasiveness at important points matched by exaggerated attention to peripheral or nonexistent influences like the Uruguayan toys of Joaquin Torres-García or the stage designs of Cleon Throckmorton.

A judicious and exhaustive survey of his subject’s access to modernism includes an account of Léonide Massine’s ballet Mercure, which Calder could not have seen, to music composed with characteristic humor by Satie, whom he never met, and sets by Picasso that suggest “a link of which Calder was entirely unaware.” Or as Perl writes rather patronizingly at the end of a lengthy essay on the historical and philosophical origins of Circus: “Is all this too much of a burden to place on the Cirque Calder? Weren’t Calder’s intentions much lighter? Didn’t he simply aim to amuse?”

This book is 687 pages long and takes Calder to 1940, when he was just over halfway through his life. Alfred Barr had already shown his work at the recently founded Museum of Modern Art in New York and commissioned an enormous mobile to hang over the entrance, which led to a Calder retrospective at MoMA in 1943 (it should make a spectacular start to Perl’s second volume). Nearly forty years later I spent a summer in Aix-en-Provence in a house borrowed from the son of Calder’s old friend the painter André Masson. I have many memories of that time in Aix—blazing blue sky, orange rocks, sweet ripe red mulberries from the great shady tree on the terrace—but the best was indoors in the salon: a Calder stabile that we carried out to set on the table when we sat talking after dinner with friends in the evenings. The stabile was, as Léger said, transparent, objective, and exact. Above all I remember its subtle equipoise, the intense pleasure it gave us, and the calming power of its presence on those long, hot Provençal nights under the mulberry tree.

This Issue

November 9, 2017

Black Lives Matter

What Are We Doing Here?

Small-Town Noir