In response to:

Freud’s Clay Feet from the October 26, 2017 issue

To the Editors:

In writing for Robert Silvers over a fifty-three-year span, from 1964 until shortly before his death last spring, I was awestruck by his critical focus on every submitted paragraph. Bob never required agreement with his views, but he demanded close analysis, independent thought, and attentiveness to possible objections. The Review will be hard pressed to match his brilliant and tireless editing. It ought to be easier, though, to emulate his vetting of potential reviewers for gross conflicts of interest.

As a model of what can go wrong, one need look no further than Lisa Appignanesi’s trashing of my Freud: The Making of an Illusion [NYR, October 26], a book that painstakingly traces Freud’s path from conventional science to arbitrary claims and the founding of a cult. That Appignanesi would greet such a study with a snide polemic was foreseeable not only from her prior role with the Freud Museum, the very headquarters of the psychoanalytic legend, but also from her publicly expressed scorn for my earlier critiques of Freudian dogma. Indeed, Appignanesi and her late husband, John Forrester—the author of Dispatches from the Freud Wars (1997), in which I figured as the principal enemy—campaigned against me in this very magazine, rounding up signatories to a dismissive letter.

Refutation of Appignanesi’s most recent charges can be found in my book, which bears only a glancing resemblance to her account of it. Here I will confine myself to just one point of fact. According to my reviewer, I falsely stated that “Freud had almost no patients in his early years”—an error that she purportedly corrects by citing his records. My assertion, however, was quite different and more damning: that in the later 1890s, when he was already calling himself a psychoanalyst, Freud had trouble convincing, successfully treating, or even retaining the clients who did cross his threshold.

In The Interpretation of Dreams Freud confessed that his patients in that period had greeted his demands for repressed infantile memories with “disbelief and laughter” (Unglauben und Gelächter). Many of them, regarding him as a crank and a bully, had simply walked out on him. Consider a sampling of his reports to Wilhelm Fliess, sent between ten and thirteen years after he first began dealing with cases of “hysteria”:

•May 4, 1896: “My consulting room is empty…. [I] cannot begin any new treatments, and…none of the old ones are completed.”

•December 17, 1896: “So far not a single case is finished.”

•January 3, 1897: “Perhaps by [Easter] I shall have carried one case to completion.”

•March 29, 1897: “I am still having the same difficulties and have not finished a single case.”

•June 9, 1899: “The ‘silence of the forest’ is the clamor of a metropolis compared to the silence in my consulting room.”

This was the Freud who was already telling readers, as he would do again and again for decades thereafter, that psychoanalytic theory had been validated by dazzling and unparalleled therapeutic success. The claim was false at the time, and it would remain false until Freud coyly intimated in 1933 that he had “never been a therapeutic enthusiast.” Here, in short, was a colossal medical fraud—one that Lisa Appignanesi is even today attempting to cover up.

Frederick Crews

Berkeley, California

Lisa Appignanesi replies:

Might I suggest that it is just a little peevish if not outright churlish of Frederick Crews to respond to my rather measured review of his vitriolic biography of Freud as a “trashing” and complain—given that he has had the run of the Review for decades—of one review taking a line on Freud different from his?

The Freud Museum London, of which I was chair between 2008 and 2014, is a museum that came into being in 1984, long after the Freud legend in which Crews is so engrossed. It is not the “headquarters” of anything. It was Freud’s last home. It has a fine archive and a program of exhibitions by artists including Louise Bourgeois and Mark Wallinger. It also organizes talks by writers, artists, academics, intellectuals, and analysts—those many cultural figures Crews would prefer never to have been interested in Freud, but who are in a multiplicity of ways.

It strikes me as odd that Frederick Crews would consider a rare dissenting letter published in the Review about one of his articles and signed by three people—John Forrester, Dr. Allen Frances, and myself—a campaign against him. Having run quite a few campaigns for English PEN while I was its president, I know the difference between a campaign and a letter. Nor was Crews “the principal enemy” in John Forrester’s many-faceted book Dispatches from the Freud Wars, though given Crews’s part in the battle against Freud that unfurled in the US in the 1990s, it would have been an aberration of history if he did not figure in the title essay.

As for the rest, only someone deaf to irony and humor would so often misunderstand Freud’s self-deprecating wit.

Freud once urged the poet H.D. never to defend him in any circumstance from “abusive comments made about me and my work…. Antagonism, once taking hold cannot be rooted out from above the surface, and it thrives, in a way, on heated argument and digs in deeper.”

I rest my case.

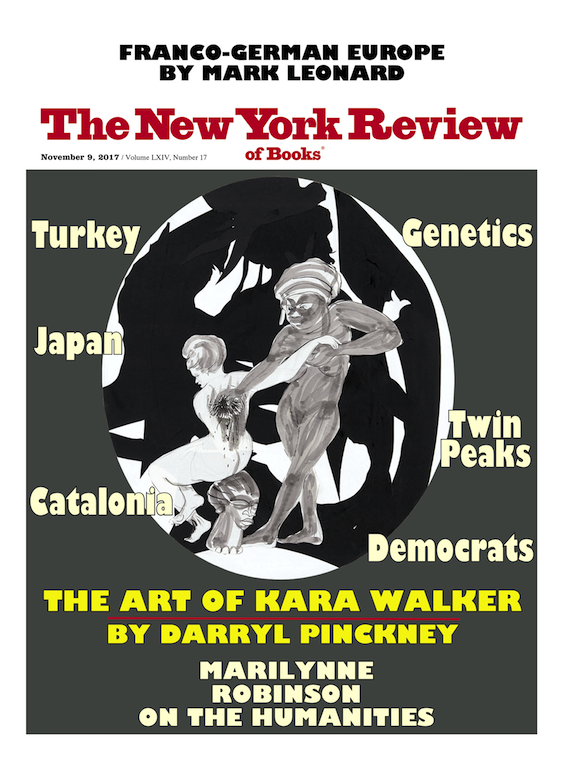

This Issue

November 9, 2017

Black Lives Matter

What Are We Doing Here?

Small-Town Noir