“Just a perfect day/You made me forget myself/I thought I was someone else/Someone good.” These lines—sung indifferently over swelling, glam rock strings—are from “Perfect Day,” an achingly gorgeous and brutally honest song by Lou Reed, who died of liver disease four years ago at the age of seventy-one. Some people thought the song was about addiction—how a junkie escaping from reality also feeds on the escape of romance. But the song could also be about how pleasurable, yet impossible, it is to escape from your true self, and about how easy it is to deceive yourself when you’ve disappointed your own expectations.

The songs of Lou Reed are a manual of sorts for how to keep living after you have let yourself and everyone else down, or after the world has done that for you. Reed doesn’t judge anyone for shooting heroin or defying societal norms, or for making sweet, gentle love to someone right before they OD. His songs are not sentimental about death, and they never, ever try to make you like the person who is singing them. He was more lacking in guile than most in rock and roll and he was notoriously cantankerous. When he had a liver transplant a few months before his death, The Onion ran a satirical piece:

“It’s really hard to get along with Lou—one minute he’s your best friend and the next he’s outright abusive,” said the vital organ, describing its ongoing collaboration with the former Velvet Underground frontman as “strained at best.” “He just has this way of making you feel completely inadequate. I can tell he doesn’t respect me at all. In fact, I’m pretty sure he’s already thinking about replacing me.”

The joke worked because it was so true: anyone who got close to Lou—bandmates, lovers, archivists—invariably had such an experience after a while.

It is a recurring theme in Anthony DeCurtis’s new book, Lou Reed: A Life. Lou goes to Syracuse, falls under the spell of a completely ruined Delmore Schwartz, writes “Heroin,” gets busted for pot, makes enemies. He moves to New York City, falls under the spell of Andy Warhol, ditches him, collaborates with the classically trained John Cale—who adds viola and avant-garde credibility to Lou Reed’s limited musicianship—forms the Velvet Underground, the most influential small-time band in the history of rock and roll, balks at sharing credit, and ditches Cale. He meets the captivating German model and barely tonal chanteuse Nico, who sleeps with him despite insisting, “I cannot make love to Jews anymore.” (Nico upheld this policy with Leonard Cohen, who never forgave Lou for his tryst.) The relationship did not end well.

And so it goes: David Bowie produces Reed’s only mainstream hit, “Walk on the Wild Side,” which many Classic Rock radio listeners don’t realize is about drag queens, and is then iced out by him for decades. Reed makes one of rock’s great self-lacerating masterpieces, Berlin (before even going to the place), and then resents producer Bob Ezrin for having his name on it. On and on and on. After a while, every time a new person comes into his life, you’re not waiting for the other shoe to drop, you’re waiting for Chekhov’s gun—except that you never know when it is going to go off, or what form the sacrifice will take.

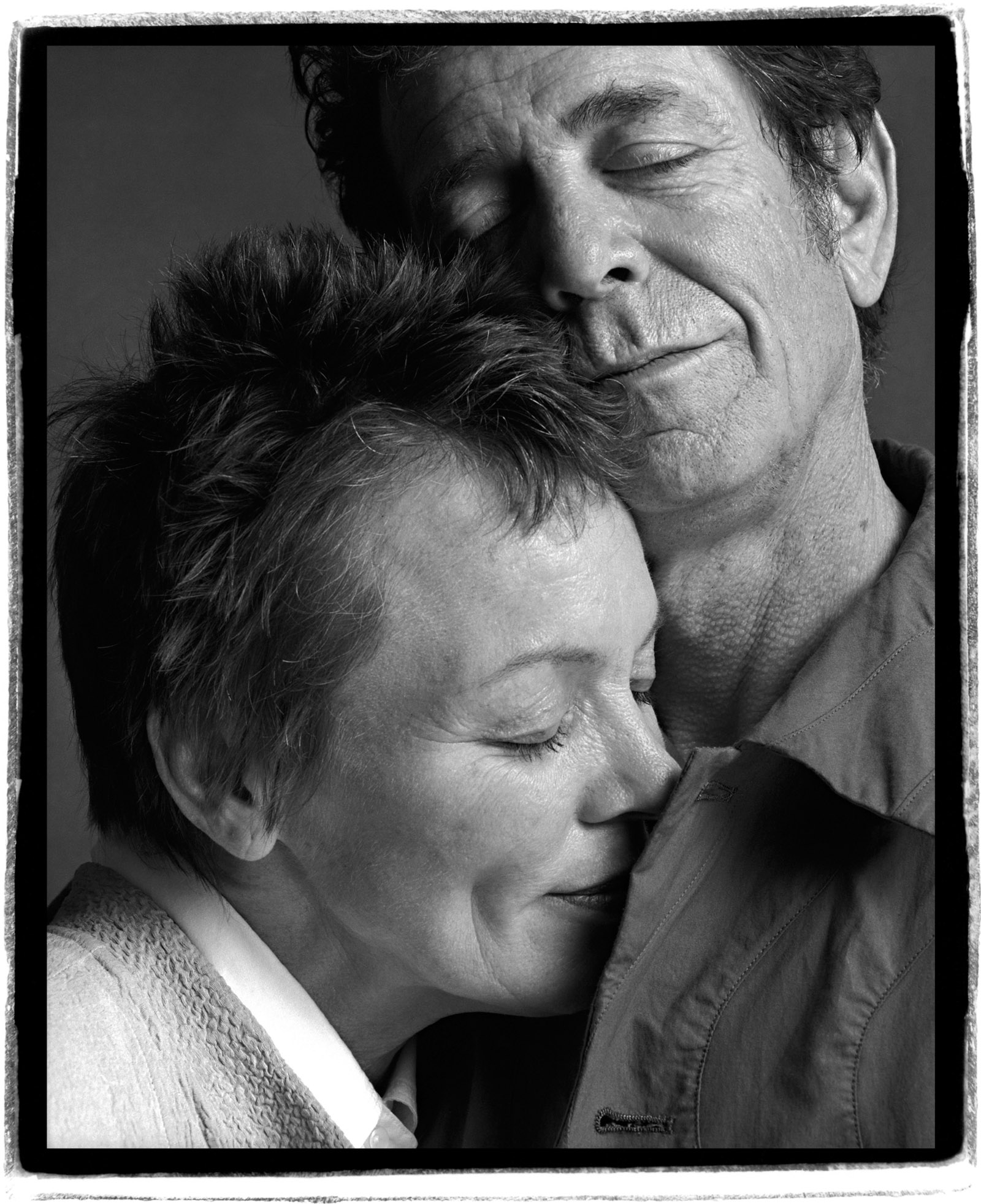

Bettye Kronstad’s account of her marriage to Reed is not for the squeamish. “Whatever joy Lou brought me, there was an equal amount of pain,” Kronstad recalled. “Lou Reed was the devil incarnate to many people.” Then came the transgender Rachel, who lived with him for three years, in a relationship described by a friend as a “marriage made in the emergency room.” After their breakup, Reed never spoke of her again. While his marriage to Sylvia Morales was falling apart, he extravagantly hit on Suzanne Vega in the presence of both Morales and Vega’s boyfriend. We are ready to have an intervention with the saintly and brilliant Laurie Anderson, Reed’s final better half, before we even meet her.

Throughout this whole business, some of it inspiring, much of it sordid, Lou Reed is consistent with nothing but his honesty and the purity of his work: he never pretends to be someone else, much less “someone good.” During her speech for Reed’s posthumous induction to the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame as a solo artist, Patti Smith, through tears, said, “You were good, Lou. You are good,” quoting the line from “Perfect Day.” And there is no question that Reed belonged there—indeed, his induction had been long overdue. But whether or not he deserves our praise as a friend, lover, and collaborator is another matter, and a central concern of DeCurtis’s book. “I do Lou Reed better than anybody,” Reed once said, about people who imitated his musical style. But how well did he do Lou Reed, the man?

Advertisement

DeCurtis is a veteran music critic for Rolling Stone as well as a prolific interviewer. Over the years he has published, in the magazine’s full transcript format, conversations with Paul McCartney, George Harrison, Keith Richards, Bruce Springsteen, Leonard Cohen, Bono, and countless other rock stars, and some of these interviews were collected in his anthology In Other Words (2005). DeCurtis had a natural rapport with Reed, too, and even quotes Reed as saying, with uncharacteristic graciousness, “People always say to me, ‘Why don’t you get along with critics?’ I tell them, ‘I get along fine with Anthony DeCurtis.’”

That little moment of sweetness would probably not have lasted much longer than a chilled-out Q&A at the 92nd Street Y, or the nearly twenty minutes of the Velvet Underground’s loud and nasty masterpiece “Sister Ray.” Reed was slightly dyslexic and had a short attention span when it came to many things, including most of the people he ever cared about.

DeCurtis admits that the biography is “not something he would ever have wanted, and while he was alive I would not have written it.” Now, four years after Reed’s death, he has given us a thorough and vivid portrait of an artist who, he shows us, was even darker than we knew. Testimony from expert witnesses—musicians, exes, friends—is balanced with thoughtful descriptions of albums that demonstrate a shrewd understanding of the music business. DeCurtis has archival interviews, anecdotes—he gave Reed’s New York album four stars in Rolling Stone and Reed told him, unsurprisingly, that he should have given it five—and accounts from intimates who, without the threat of a living Lou Reed, tell stories that are less than sweet. A young artist and fan named Duncan Hannah received this pickup line from his hero: “Well, look, why don’t you come back to my hotel with me?…And you can shit in my mouth.” When that didn’t work, Reed offered, “I’ll put a plate over my face, then you can shit on the plate. How’d you like that?”

Lou Reed liked to say that his childhood was so terrible that he blocked out everything up to around age thirty-one. His memory of PS 192 was free of nostalgia. “I couldn’t have been unhappier than in the eight years I spent growing up in Brooklyn,” he recalled. There was no radio and no escape. “The playground was concrete and they had lunch monitors…. People were pissing in the streets. A kid had to go to the john, you raised your hand, got out of line, and pissed through the wire. It was like being in a concentration camp, I suppose.”

The only thing worse was adolescence in Freeport, Long Island, and the only thing worse than that was submitting to electroshock treatments for the crime of exploring his sexual fluidity as a teenager. He never forgave his parents, and he made them pay in song after song, including “Kill Your Sons”:

All your two-bit psychiatrists are giving you electro shock

They say, they let you live at home, with mom and dad

Instead of mental hospital

But every time you tried to read a book

You couldn’t get to page 17

’Cause you forgot, where you were

So you couldn’t even read

Don’t you know, they’re gonna kill your sons

He made his listeners relive the experience in Metal Machine Music (1975), an entire album devoted to the aural simulation of electroshock with guitar feedback and noise—no hooks, no melodies, no lyrics, no free jazz–level chops. The liner notes ended with this kicker: “My week beats your year.”

At Syracuse, Reed hosted a free jazz radio show and edited a literary journal called Lonely Woman, named for the Ornette Coleman song. He played in R&B cover bands at frat parties and studied with Delmore Schwartz, the first of a few crucial father figures, who was nearing the end of his tortured life and believed that Nelson Rockefeller was tapping his phone. (Other substitute patriarchs for Reed included Warhol and the songwriter Doc Pomus.)

Schwartz, Reed would recall, was the first great person he knew. While Schwartz hated rock and roll, Reed would take what he loved of the poet’s work—along with the work of Raymond Chandler, William Burroughs, Allen Ginsberg, Hubert Selby Jr., and others—and combine it with three chords and his view of the truth. Bob Dylan’s version of combining literature and rock and roll was already changing the world. Reed, who admired Dylan and hated the Beatles, threw in androgyny, more explicit hard drug references, and a Brooklyn accent. Reed had literary ambitions, but wanted to realize them with an amplifier.

Advertisement

Reed then founded and dominated the band that would cement his legacy—the Velvet Underground. One of the few people cool enough to be familiar with their work while they existed was the young Václav Havel. (They had an awkward interview, two decades later, when Havel had to beg Reed to perform a gig for free in the Czech Republic.)

It is an undeniable irony that the least commercial of legendary rock and roll bands had its first sponsor, pseudo-manager, and pseudo-producer in Andy Warhol, the original King of Pop. Warhol understood fame better than anybody, yet his aura, his imprimatur, and his vision—not to mention his electric banana print on the cover of their first album, The Velvet Underground and Nico (1967), with his name displayed more prominently than theirs—could not get this band beyond venues as underground as their name. Among their gigs was a stint at the Dom on St. Marks Place that included dancers and whip artists. Warhol would screen his own nonnarrative films over the band while they played. A friend of Reed’s said the scene was “like a Fellini movie—but squared.” After they dropped Warhol, the band played only third-rate gigs. (1969: The Velvet Underground Live was recorded in a Dallas club, where just a few weirdos showed up.)

The people who did take notice—and the sales figures for The Velvet Underground and Nico were, according to DeCurtis, slightly less anemic than legend would have it—were hearing songs about worlds of darkness and confusion that previously had no soundtrack. These were songs about searching for your mainline, about hating your body and all it requires in this world, about tasting the whip of love not given lightly, about being a callow boy run ragged by a femme fatale (sung by Nico, herself a legendary femme fatale). They featured lots of desperation, a little fun, and enough noise to make the engineer of White Light/White Heat (1968) leave the studio in protest.

It was when the band was about to stop playing that word got around about their shows at Max’s Kansas City on Park Avenue South, where they had an extended residence throughout the summer of 1970. While they did not fill the house every night, they were generating buzz. “Reed was comfortable at Max’s, mingling easily with the crowd of musicians, writers, publicists, record company execs, and artists, all of them fans of the band,” writes DeCurtis. They were finally finding an audience while they were recording their final album, Loaded (1970), whose songs “Rock and Roll” and “Sweet Jane” actually received some radio play.

But Reed started losing interest in the sessions, using up his voice on the shows and allowing Doug Yule, Cale’s less threatening replacement, to sing some of the classics (“New Age,” “Oh! Sweet Nuthin’,” “Who Loves the Sun”) in his quavering, sweet, irony-free voice. Loaded ultimately received a rave review in Rolling Stone, but while it was being finished in the studio, Reed left the band, and they ended up butchering the mix—including cutting the bridge to “Sweet Jane”—perhaps as revenge. The rest of the band attempted, but ultimately failed, to steal credit for the songs that Reed wrote on his own.

If he had stayed for one more album, the Velvet Underground could have broken through to the mainstream, but the fact that they didn’t is better for the legend. The band anticipated various cultural moments, including punk, new wave, college rock, alternative rock, and grunge. When their albums were reissued in the 1980s, they were treated as a kind of holy grail, something that their contemporaries weren’t ready for yet, inspiring hope of a musical future for many underground bands to come. And it wasn’t just the feedback rush of “White Light/White Heat” that sealed their legacy, but the dark and brooding ballads “Pale Blue Eyes,” “Jesus,” “I’m Set Free,” and so on, where you could hear Reed actually crooning with great tenderness.

One of the original Velvet Underground fans was David Bowie, who recorded a cover of “I’m Waiting for the Man,” and, fresh from The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust and the Spiders From Mars (1972), approached RCA with a proposal to produce Reed’s second solo album. The resulting album was Transformer, released in 1972, less than a year after Reed’s eponymous debut (which went nowhere). The timing was perfect. A few years earlier, “Walk on the Wild Side” would not have been a hit, and a few years later, it would not have seemed quite so wild. Reed’s flirtations with transgender identity and androgyny were just edgy enough for the young rebels and just vague enough to be legal. Transformer lived up to its title, both in its play on gender and in its effect on Reed’s career.

The melodicism of Transformer, in contrast to its bleak subject matter, would continue in Berlin (1973). After that, Reed would occasionally be musical in the lower reaches of his range when the song called for it. Sometimes the effect was hypnotic, as in much of his devastating album about cancer and bereavement, Magic and Loss (1992). But often, he couldn’t be bothered. He would shout, or bark, or talk or grunt. He was a lyrics person first. He loved the sound of Dion, but knew he couldn’t aspire to that. Still he could be something. When he wanted to, he sounded so sweet that it was hard to believe it was him.

And yet as self-absorbed as Reed often seemed to be, he couldn’t have created everything he did without being a superb listener. So many of his subjects, after all, were real people. There was Candy Darling, née James Slatterly, of the Warhol Factory, a transgender actress who yearned to be Marilyn Monroe. She was one of the figures who told everyone in 1972 to “take a walk on the wild side.” And then there was Caroline, in “Caroline Says,” who tells her lover, “as she gets off the floor/You can beat me all you want to/But I don’t love you anymore.” (That one could have been transcribed at home.) He is the voice of his beloved Delmore Schwartz in “My House,” and, reunited with John Cale, he told Andy Warhol’s life story in the song cycle Songs for Drella (1990). Reed did not need to be a nice guy. Without pretense, he reached from deep within himself and gave us these astonishing creations. He wrote Magic and Loss, he said, because he was losing two friends to cancer and no one had made an album about that.

Even though DeCurtis and other rock critics interviewed Reed throughout his career, the book is not heavy on Reed’s own accounts of his personal life, and if it feels a bit skeletal in this regard, there is a reason. Laurie Anderson, who wrote eloquently about her late husband for Rolling Stone, and spoke movingly at the posthumous Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction, would not be interviewed for this book. In her breathtaking speech about Lou, she gives us a portrait of a man who was wonderful and fascinating:

Lou was a wirehead. He loved gear, he loved good sound. He was a photographer and an inventor. He was a warrior, a tai chi and eagle claw practitioner. He was a great dancer, he could take watches apart and put them back together, he was kind, he was hilarious, he was never ever cynical.

Lou was my best friend and he was also the person I admire most in the world. In the twenty-one years we were together there were a few times when I was mad and there were a few times when I was frustrated but I was never, ever bored.

Where was the Lou who was “never ever cynical”? He was certainly in Anderson’s memories, but where else? Perhaps Anderson will write a memoir, and it could be as lyrical and elegiac as Patti Smith’s Just Kids.

What we do have are the accounts from Reed’s albums, as intimate in their affections as they are in their hostilities—from the playful adoration of Set the Twilight Reeling (1996), to the ruthless documentation of his own cruelty on Ecstasy (2000). These two albums give you a sense of how he treated the love of his life. Here, in “Mad,” is an example:

Mad, you just make me mad

I hate your silent breathing in the night

Sad, you make me sad

When I juxtapose your features, I get sad

I know I shouldn’t had someone else in our bed

But I was so tired, I was so tired

Who would think you’d find a bobby pin?

It just makes me mad, makes me mad

It just makes me, makes me

Mad

And he’s just getting started. Why, most people might wonder, was he the one to be mad? But Anderson played violin on the album, and she got something about this man no one else could. Here, after all that, is her account:

Lou taught me a lot about love and I found out what it is to love and to be completely loved in return. This will be a part of me for the rest of my life. It’s also something that changes you forever to have the love of your life die in your arms and when Lou died in mine I watched as he did tai chi forms with his hands. And I watched the look of joy and surprise that came over his face as he died and I became less afraid. One more thing he taught me.

This is beyond being someone good and someone evil. This is about what Reed called “the power of the heart.” It was about that very subject that Reed refused disclosure. In 2006, when DeCurtis was moderating a chummy public chat with Reed, an audience member asked an innocuous question about one of the sweetest songs in his catalog, “Set the Twilight Reeling,” an unabashed ode to Anderson. It was not an invasive question, but Reed responded as if it were:

I have to tell you seriously I don’t like analyzing what I write, and I don’t like talking about growing up. I don’t like talking about personal things—ever, of any type, because I put it all in the songs, and then I feel uncomfortable talking about it.

It is the job of the biographer to do precisely the thing Reed said he never ever wanted to do—to answer the questions Reed never wanted to answer. What was he thinking? What did he mean by that? Why did he live his life that way? He wrote songs to avoid answering these questions.

Lou Reed gave us Jackie in his corset, Jane in her vest, Candy hating her body and its worldly requirements, and Severin tasting the whip of shiny, shiny leather. Reed did some things that were inexcusable, maybe unforgivable, though that’s not up to us to decide. He filled our emptiness with these characters, and by doing Lou Reed better than anybody. And if we listen closely, we can walk down the street in leather and sunglasses, convincing ourselves that no one can touch us.

This Issue

November 23, 2017

The Pity of It All

Poems from the Abyss

Virgil Revisited