It was August 2004, and the Iraqi insurgency was raging in Anbar province. Major General James “Mad Dog” Mattis of the Marines, who is now the Trump administration’s defense secretary, called a meeting with a group of religious leaders outside Fallujah. His division was coming under daily fire from both local militants and foreign terrorists associated with al-Qaeda’s affiliate in Iraq, and he hoped to persuade the leaders that it was misguided of them to encourage local young men to pick up rifles and shoot at American forces rather than trying to throw out al-Qaeda, whose bombings and beheadings were transforming their province into a hellscape.

“How could you send your worshipers, some of them young boys, against us when their real enemy is al-Qaeda?” Mattis asked them, according to the military analyst Mark Perry in his new book, The Pentagon’s Wars: The Military’s Undeclared War Against America’s Presidents, a history of high-level Pentagon decision-making and of relations between uniformed and civilian executive branch officials over the past quarter-century. Perry goes on to repeat further details about this meeting drawn from Bing West’s The Strongest Tribe: War, Politics, and the Endgame in Iraq (2008). When the religious leaders continued sipping their tea, Mattis shouted: “They’re kids…. Untrained, undisciplined teenagers. They don’t stand a chance.” Later, Mattis told West that the tribes at the time “only saw us as the enemy”; what was needed was for al-Qaeda’s militants to make mistakes and “expose themselves for what they were.”

Al-Qaeda’s tactics did eventually repulse Anbar’s tribes enough for them to band together in the so-called Sunni Awakening and drive the foreign terrorists out. The reprieve was temporary; the remnant of al-Qaeda’s Iraq affiliate would regenerate across the border in Syria, rebrand itself as the Islamic State, and sweep back into Iraq in 2014. But for a few years, Anbar became a somewhat less dysfunctional and dangerous place, as Mattis had thought it could be.

More than a decade later, Mattis, now in a civilian position, is once again trying to navigate a tricky and dangerous situation. Widely regarded as one of the “grown-ups” in the idiosyncratic Trump administration, he is among the striking number of military men with whom Trump has chosen to surround himself. Trump appointed another retired four-star general, John Kelly, as his homeland security secretary, then elevated him to White House chief of staff. He made an active-duty three-star general, H.R. McMaster, his national security adviser. McMaster’s chief of staff is a retired three-star general, Keith Kellogg, and many of the lower-level policy specialists gradually succeeding Obama-era holdovers at the National Security Council also have military backgrounds. As a result, the upper reaches of the executive branch, which felt at times like a law firm under Obama, are coming to resemble a command post.

This spreading militarization of the executive branch makes it timely to think about the experiences that have shaped the past generation of top Pentagon brass. The most important of Trump’s military men—along with General Joseph Dunford, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, who was appointed to that position by Obama—share a remarkably narrow range of experience. Mattis, Kelly, and Dunford are all Marines, the smallest of the military services and the one that has the greatest reputation for cultural conservatism and for a warrior identity. They have also known one another and worked together for a long time: Kelly and Dunford even served in the unit that Mattis commanded in Anbar. While McMaster is an Army officer, he also came up fighting insurgents in the post–September 11 Muslim world.

Some of The Pentagon’s Wars’ most interesting passages focus on these men. Perry writes that observers might like to believe that their familiarity “with the terrible costs of war” would make them “unlikely to support the military interventions that had marred the terms of the four previous presidents.” But he is skeptical about this, pointing to various episodes in their backgrounds that suggest that “each of these four officers believed deeply in American military power—and in its ability to shape the international environment.” He adds:

Senior military commanders who knew and had served with Mattis, Kelly, Dunford, and McMaster now regularly reassured the press that the election of Trump would not lead to an upending of America’s traditional role as the enforcer of global stability. The war on terrorism would continue, the defense budget would be increased, the US military would be strengthened, and, as Donald Trump reassured the public, the United States “would start winning wars again.”

There is already a growing disparity between Trump’s rhetoric as a candidate and his foreign policy decisions. For all his campaign talk about being eager to “bomb the hell out of” the Islamic State, he ran for president as something of an isolationist—an opponent of military missions that did not put “America first”—and at times even portrayed himself as more dovish than Hillary Clinton. For instance, he criticized George W. Bush’s invasion of Iraq (ignoring the inconvenient truth that at the time, he had told Howard Stern that he supported it), for which Clinton had famously voted, and he denounced her advocacy of Obama’s ill-fated 2011 intervention in Libya. In a major foreign policy speech in April 2016, Trump said: “Unlike other candidates for the presidency, war and aggression will not be my first instinct. You cannot have a foreign policy without diplomacy. A superpower understands that caution and restraint are really truly signs of strength.”

Advertisement

In a series of moves starting just days after he took office, Trump has approved Mattis’s requests to give the military more freedom to attack Islamist militants at its own discretion, removing Obama-era constraints on drone strikes and commando raids in places like Yemen and Somalia. In April, after the Syrian government used chemical weapons against civilians, Trump ordered a punitive missile strike on an Assad regime air base without offering any public explanation of his rationale for how it complied with the constraints imposed by the international laws of war.

In August, Trump answered the military’s request for more troops in Afghanistan by authorizing a new surge of thousands of additional American forces there, winding back up a sixteen-year-old war that Obama had tried to wind down. In explaining his decision in televised remarks, Trump denied that the United States was resuming a nation-building mission in Afghanistan, saying instead that the forces were there only to kill terrorists. But he conceded that he had been talked into changing his position on troop levels out of fears that terrorists would flow into the vacuum left behind if American forces departed. “My original instinct was to pull out—and, historically, I like following my instincts,” he said. “But all my life I’ve heard that decisions are much different when you sit behind the desk in the Oval Office.”

In October, after the deaths of four American army soldiers in an ambush in Niger focused attention on a build-up of hundreds of American forces there, a deployment that began under Obama and expanded under Trump, Mattis testified that the administration had sent the troops to be trainers and advisers who would help that nation resist incursions by Islamic State fighters: “Why did President Obama send troops there? Why did President Trump send troops there? It’s because we sensed that as the physical caliphate is collapsing, the enemy is trying to move somewhere.” Mattis added, “We’re trying to build up the internal defenses of another country so they can do this job on their own.”

Perry explains that The Pentagon’s Wars “is not a recounting of America’s recent wars, but a narrative account of the politics of war—the story of civil-military relations from Operation Desert Storm to the rise of the Islamic State.” For those hoping that a skeptical, assertive military mindset is exactly what is needed to restrain the potential excesses of the Trump administration, Perry’s portrayal of many of the most important Pentagon leaders of the past generation may be disturbing. He deplores the “professional, and inbred, military establishment” of the post–cold war era, writing that all too often three- and four-star officers have been weak, ego-driven, and self-promoting, while rarely independent and outspoken enough to stand up to presidents who advance bad ideas.

The bad ideas Perry has in mind are protracted nation-building missions. He is critical of many of the United States’ military interventions abroad in places like Somalia, Haiti, Kosovo, Iraq, Afghanistan, and Libya, believing that they squandered the US’s position of strength at the end of the cold war. He acknowledges that civilian control of the military is a hallmark of our democracy. But he suggests that—confronted by a series of “political leaders whose vision of a world made safe by American arms, with nations rebuilt according to our ideals” was doomed to fail—senior military officers have too often fallen into line instead of offering unvarnished advice: they should have more aggressively “insisted that our civilian leaders question their assumptions or rethink their options.”

This sounds more like a tale of unduly supine generals than of a Pentagon that has been engaged in an undeclared war against America’s presidents. Indeed, The Pentagon’s Wars contains only a few episodes that live up to its provocative subtitle. In Perry’s account, the most striking instance in the last twenty-eight years of a senior military officer telling a president “no” came when General Colin Powell, then the chairman of the Joint Chiefs, rebelled against President Clinton’s attempt in 1993 to let gays and lesbians serve openly in the military. Powell’s revolt, resulting in the “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” compromise, was a “triumph” of sorts, Perry writes, because henceforth, “for the first time in history, the head of the military had a veto: Clinton believed he couldn’t successfully promote a military policy decision without his concurrence.” Yet Powell’s victory for the institutional clout of the military may have been pyrrhic: in Perry’s telling, the nation’s top civilian officials since then have “purposely named military officers they believed they could control” to influential positions, rewarding those who salute and agree and stifling those willing to express dissent.

Advertisement

Whatever one makes of Perry’s arguments, the analytical portions are his book’s most interesting and valuable component. But its factual portions have certain limitations. First, The Pentagon’s Wars contains very little new information. As the endnotes make clear, the essential details of most of the meetings and events it recounts are taken from previously published books and articles by journalists like Michael Gordon, Thomas Ricks, David Halberstam, and Bob Woodward, and from memoirs by retired generals and other former national security leaders. Although Perry conducted many interviews, a typical passage of his book will lay out a well-established episode based on material already put forward by others and then append a new minor detail or observation about it.

Second, the contributions of his Greek chorus of mostly anonymous sources are often jarringly gossipy. We are told, for instance, that Army General Norman Schwarzkopf, the leader of the first Gulf War, under pressure just before the start of the air campaign, was “almost whimpering” and “acting like a baby.” General Wesley Clark, who led the Clinton-era interventions in the Balkans as the head of European Command, was a “tireless self-promoter…who’d gotten ahead by rubbing shoulders with the right people, endlessly polishing his own credentials—and by his singular focus on himself.” Air Force General Richard Myers, the chairman of the Joint Chiefs during the Bush administration’s invasions of Afghanistan and Iraq, “never disagreed with his boss,” to the point that he was supposedly called “limp Dick” behind his back. While Perry writes that Mattis was a “fearless fighter and plain talker” as a battlefield commander, he also quotes an unnamed former subordinate Marine who describes Mattis as a back-slapper who displayed a need to “parade his masculinity” among lower-ranking troops by swapping stories about women they knew.

Whatever the value of this kind of snark, it’s not clear how much credence to give it. I took a closer look at one of the few bits of original reporting about one of the generals who went on to work for Trump and came away unconvinced that it was true. Perry recounts an acrimonious phone call between Mattis and Tom Donilon, then Obama’s national security adviser, in December 2012. At the time, Mattis was in charge of the US Central Command, which oversees military operations in the Middle East, and he was developing a reputation for favoring a more aggressive approach to curbing Iranian misbehavior than some of Obama’s civilian advisers. According to the book, Mattis unilaterally moved a carrier group closer to Iran, and Donilon, when he noticed, told Mattis to pull it back. But Donilon told me that neither the phone call nor the carrier group incident ever happened. I then talked to half a dozen former White House and Pentagon officials who were in a position to know about it, and none remembered the incident either.*

Finally, Perry made some puzzling choices about what to omit. The book largely ignores the unusual policy issues that arose after September 11 and led to recurring battles between civilian and uniformed officials in both the Bush and the Obama administrations. There is no discussion of Guantánamo or trying terrorists before military commissions, for example, and only a fleeting reference to torture amid a brief mention of the Abu Ghraib scandal.

The absence of these crucial issues in a history of recent civilian–military relations is glaring, and is all the more unfortunate because their inclusion would have helped to illuminate significant moves by Trump’s generals. For example, one of Mattis’s early accomplishments as Trump’s secretary of defense was to persuade the president to abandon his campaign promise to sanction the use of torture for interrogating suspected terrorists. Another example is Kelly’s decision, on his first day as Trump’s chief of staff, to send a draft executive order on detainee policy, which had been nearly ready for Trump’s signature, back to lower-level staffers across the various security agencies for reworking so that its final language might better lay the groundwork for putting Guantánamo, which Kelly had overseen during the Obama years as leader of the US Southern Command, to a wider use.

In making sense of those moves, it helps to know that during the Bush administration, many (though not all) uniformed military leaders pushed back hard against civilian officials’ desire to bypass the Geneva Conventions when it came to abusive interrogations of wartime detainees. And it helps to know that during the Obama administration, foot-dragging Defense Department officials sometimes put up passive resistance to the White House’s policy of trying to empty Guantánamo. Including those civilian–military fights over policy during the war on terror would have better supported the book’s subtitle—and made it even more timely for the Trump era.

But there is ample material in The Pentagon’s Wars to raise an important question about the Trump administration: Are Trump’s generals cut from the same mold as their recent Pentagon colleagues, whom Perry sees as having been yes-men? There is some evidence to believe they are not. Even if the purported carrier group incident is dubious, it is widely agreed that Mattis’s hawkish views on Iran created tensions with the Obama administration. When he ran Southern Command, Kelly was also known for candidly saying what he believed even when it put him at odds with the White House, as when he blamed a major 2013 hunger strike at Guantánamo on Obama’s de facto abandonment of his effort to close the prison in his administration’s middle years. And McMaster, as Perry reminds us, wrote a book that became influential in military circles called Dereliction of Duty: Lyndon Johnson, Robert McNamara, the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the Lies That Led to Vietnam (1997). In it, he condemned the Joint Chiefs for failing to forcefully question (or resign in protest against) Johnson’s disastrous escalation of the Vietnam War.

Against that backdrop, one of the striking patterns during the first year of the Trump administration has been the repeated spectacle of these current and former military men contradicting or brushing off the commander-in-chief. Some of this has come in culture-war episodes, such as the debate over transgender troops. After Trump abruptly declared on Twitter that transgender people would no longer be permitted to serve in the American military “in any capacity,” Dunford said that transgender troops could remain unless and until some more formal directive arrived from the White House. When the Trump White House finally produced such a document, Mattis launched a lengthy study during which transgender troops would be permitted to keep serving. And Dunford later testified that his advice was that currently serving transgender troops should be permitted to stay in the military after all, raising the possibility that the president’s edict may fade away.

Another example came after the racially tinged violence surrounding the marches in Charlottesville sparked by the city’s plan to remove a statue of Robert E. Lee. After Trump prompted widespread outrage by equating the white supremacist protesters with anti-racist counterprotesters, Mattis gave a speech to troops that took a starkly different tone, urging the military to “just hold the line until our country gets back to understanding and respecting each other.”

Kelly complicates this pattern. In some ways he has looked like a restraining force, using his power as chief of staff to impose order on the chaotic White House by regimenting the flow of information to Trump and supporting the ouster of several of the most unconventional staffers of his administration, such as Anthony Scaramucci, the foulmouthed and short-lived White House communications director, and Stephen Bannon, the head of Breitbart News whom Trump had made his chief strategist. Those moves echoed a similar overhaul and purge at the National Security Council launched by McMaster last spring and summer, after he took over as Trump’s national security adviser.

But Kelly has also done things that looked more accommodating to his boss—and not just carrying out, as homeland security secretary, Trump’s first, poorly designed travel ban, which caused chaos before courts blocked it. In October, after a Democratic congresswoman criticized Trump over his apparent botching of a consolation call to the widow of one of the soldiers killed in Niger, Kelly came to the White House podium to invoke the combat death of his own son, while attacking the lawmaker as an “empty barrel” whom he had once witnessed crassly bragging, at the dedication ceremony for an FBI building in Miami named after two slain agents, about how she had used her access to President Obama to secure funding for the project. When video of the ceremony surfaced showing that Kelly’s accusation was false, he refused to apologize. His performance drew a rebuke from retired Admiral Mike Mullen, who served as chairman of the Joint Chiefs from 2007 to 2011, and who agreed with an interviewer in November that Kelly now appeared to be “all-in” on supporting Trump as a policy matter:

Certainly what happened very sadly a few weeks ago, when he was in a position to both defend the president in terms of what happened with the gold star family and then he ends up—and John ends up politicizing the death of his own son in the wars. It is indicative of the fact that he clearly is very supportive of the president no matter what. And that, that was really a sad moment for me.

Still, for all the turbulence of these culture-war moments, and for all the slow-burn escalation of counterterrorism deployments, the military men’s most important contribution may be in restraining full-scale war. This past summer, for example, in response to North Korea’s provocative testing of more powerful nuclear weapons and longer-range missiles, Trump declared that “talking is not the answer.” But Mattis contradicted him just a few minutes later, telling reporters: “We’re never out of diplomatic solutions.” Similarly, when Trump told reporters he might use the American military to intervene in Venezuela amid deepening unrest there, McMaster swiftly reassured the world that “no military options are anticipated in the near future.”

Mattis has also repeatedly reaffirmed America’s unconditional support of NATO after Trump called it into question, and said publicly that it was in America’s interest to stay in the Iran nuclear deal, even as Trump threatened to abrogate it. In November, Air Force General John Hyten, the commander of the US Strategic Command, which controls the United States’ nuclear weapons, told an audience at a security forum that if Trump gave him an “illegal” nuclear attack order, he would reject it and try to steer the commander-in-chief toward lawful options.

In short, Trump’s generals—some still in uniform, some now civilians—are clearly trying to mitigate turmoil and curb potential dangers. That may be at once reassuring and disturbing. In the United States, the armed forces are supposed to be apolitical. While the nation should be grateful in these troubled times that the military as an institution has remained loyal to constitutional values, Ned Price, a former CIA officer who served on the National Security Council under Obama, wrote in an essay in Lawfare that the military’s very act of contradicting or distancing itself from the president, even subtly, “goes against the grain of our democratic system and should engender at least fleeting discomfort among even the most virulent administration critics.” Thus, even if it is a good thing for now that the line between “civil and military affairs in American society” is getting a bit blurred, in the long run, Price warned, “that line must again become inviolable when our political class returns to its senses.” Or as Mullen, in a speech in October at the US Naval Institute, put it:

How did we get here to a point where we are depending on retired generals for the stability of our system? And what happens if that bulwark breaks, first of all? I have been in too many countries globally where the generals, if you will, gave great comfort to their citizens. That is not the United States of America.

The more immediate question, however, may be whether Trump’s generals will last through the Trump presidency. McMaster is a regular target of far-right media outlets that see him as a threat to Trump’s nationalist agenda and have urged the president to fire him. And in late August, Trump, who hates being managed, lashed out at Kelly, who later reportedly told other White House staffers that he had never been spoken to like that in his thirty-five years of public service and that he would not abide such treatment in the future. While Mattis so far has escaped Trump’s penchant for abusing his subordinates, it seems safe to predict that he too will eventually get on the mercurial president’s wrong side. In the meantime, it looks increasingly as though Mattis’s long-ago meeting outside Fallujah, asking over tea that the religious leaders of Anbar province see reason, foreshadowed his final mission: trying, on a far larger scale, to keep things from spinning out of control at home.

This Issue

February 8, 2018

To Be, or Not to Be

Female Trouble

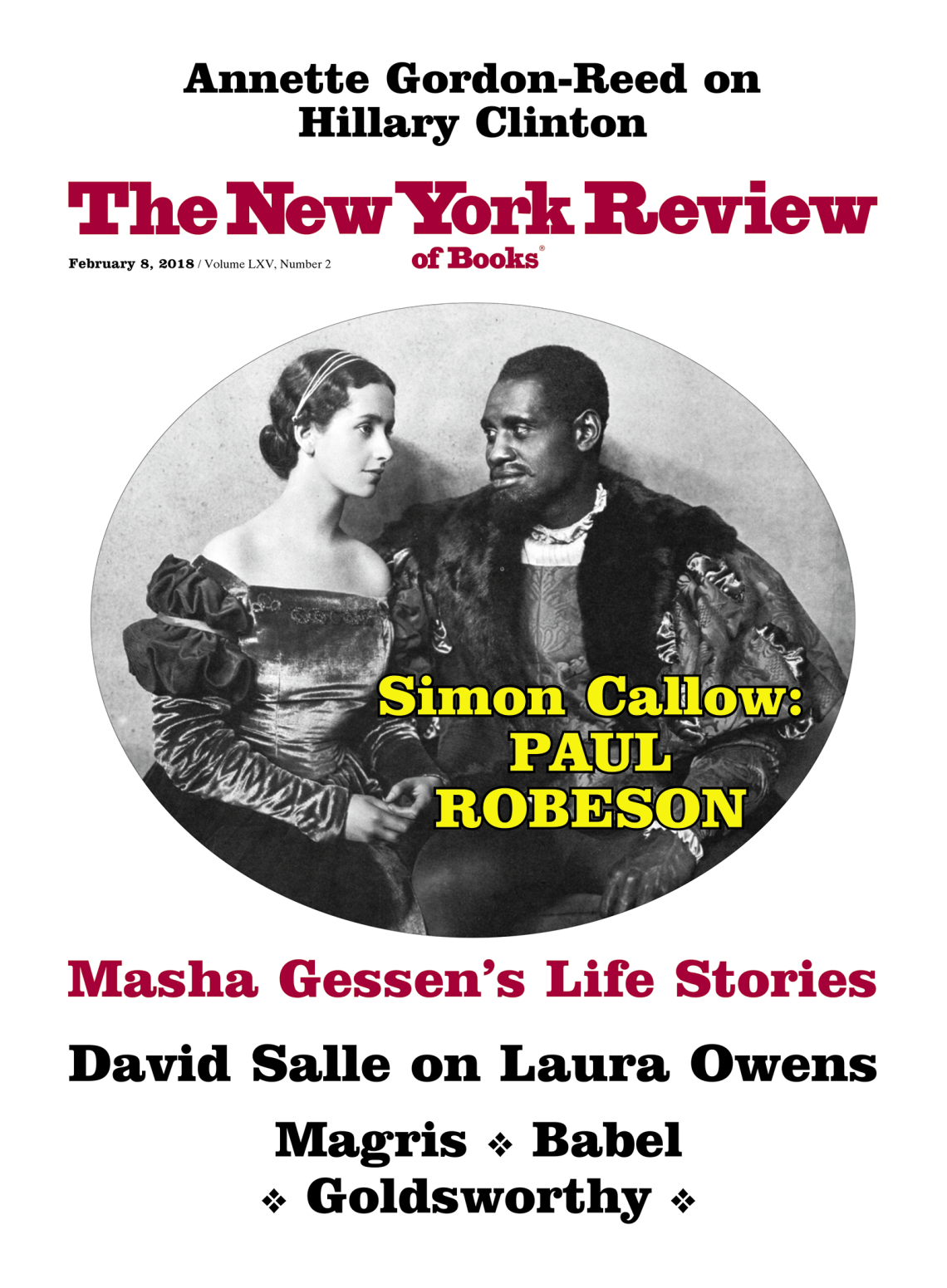

The Emperor Robeson

-

*

Others who told me they thought this story was false included Jeremy Bash, the chief of staff to former secretary of defense Leon Panetta; James Miller, the former undersecretary of defense for policy; and John Allen, a now-retired Marine general who was formerly Mattis’s deputy commander at Centcom. I received no answer when I reached out to Mattis through the Pentagon press office. ↩