As a pitch, it would have sounded unpromising. A TV drama set entirely among the ultra-Orthodox Jews of Jerusalem, the men black-hatted, bearded with side curls, most of the women bewigged, their sleeves long and their skin covered up; the action centered on one family, specifically a widowed father and his unmarried son, sharing a cramped apartment, each sleeping on a narrow single bed; storylines touching on bereavement, the fading health of an elderly mother, power struggles within a religious elementary school, and the search for, if not necessarily love, then a person with whom it might be possible to share a life and make a home. No nudity, no profanity, no touching, and certainly no sex.

There cannot be many TV executives who would rush to greenlight that one. But in 2016 Marta Kauffman, co-creator of Friends, announced that she had bought the rights to Shtisel, a hit show on Israeli television’s YES network, and that she planned to adapt the series for Amazon Prime. Her version will be called Emmis, Yiddish for truth; it will be located in Brooklyn rather than the Geula neighborhood of Jerusalem; and its primary language will be English rather than Hebrew, though it’s possible the characters will lapse into subtitled Yiddish when the situation demands it, as they do in the original.

Shtisel, named for the family at the heart of the saga, will thus take its place alongside a series of successful Israeli TV exports. Showtime’s Homeland began life as Hatufim, while HBO’s In Treatment, following a therapist and his patients over successive fifty-minute sessions, was a translation of BeTipul. Meanwhile, Netflix viewers have lapped up Fauda, a thriller about an undercover intelligence squad and its Palestinian targets. So Shtisel comes with a good pedigree, or yichas as Rabbi Shulem Shtisel might put it.

And yet it stands apart from the others. While those programs dealt with the lives of contemporary, nonreligious Israelis—who would at least look recognizable to the average Netflix viewer—Shtisel inhabits a subculture whose mores would strike most Americans, or indeed most people who lead secular lives, as utterly alien. It takes as given that characters murmur a bracha, or blessing, before eating or drinking anything; that most hours of a man’s day are devoted to studying the often abstruse teachings of centuries-old texts; and that no one would so much as think of using a phone or riding a bus during the prohibited hours of the Sabbath. Crucially, men and women observe the strictest rules of propriety. If they are not married to each other, and they are in a room alone, the door will always remain open. If they are married, they sleep in separate twin beds.

Put like that, Shtisel might sound like The Handmaid’s Tale dubbed into Yiddish. But while religious rules set the boundaries for the lives on screen, they are not at the center of the action. These obligations are assumed by the characters and, before too long, the viewer assumes them too. As a result, the focus remains on the people of the story, their trials, their longings, their memories, their ambitions—most of which are modest, on the scale of a regular human life.

And yet the success of Shtisel points to a larger story—one about twenty-first-century Israel and its changing composition, about Zionism and the strange paradox of unintended consequences, and about the persistence of faith in the era of globalization and technological progress.

Still, those wider meanings are not what you see on screen, or what drew large numbers of Israelis to watch the show, or what will doubtless lure millions more to follow the English-language adaptation. Instead, what you see is the quiet struggle of human beings, a universal story exquisitely told.

Viewed one way, Shtisel is a reworking of that best known of all Yiddish tales, Sholem Aleichem’s Tevye and His Daughters, the inspiration for Fiddler on the Roof. But while Tevye struggled to marry off his girls, the recently widowed Shulem Shtisel toils to find a wife for his youngest, most difficult son, Akiva. The boy is, says one matchmaker, a “screw-up,” twenty-seven years old and still without a bride after several false starts. In his world, men are expected to become engaged after a single, arranged meeting—usually coffee and cake in a hotel lobby—the girl chosen for him by his parents, the couple-to-be barely into their twenties.

Akiva tries to take that conventional path, several times. But while his father, a lifelong teacher at a cheder, and his brothers are satisfied with the life tradition prescribes for them—in which study is the only possible vocation—“Kiva” is a dreamer, never without a small exercise book in which he sketches ducks in a pond or the occasional flower. By the second season, this artistic passion of Akiva’s will have blossomed, or escalated, into an existential crisis for both him and his father. (There is a nod here to the 1972 novel My Name is Asher Lev, Chaim Potok’s portrait of the artist as a young Hasid.)

Advertisement

Meanwhile, Shulem has troubles of his own. In need of a wife, he too avails himself of the services of a matchmaker. But no woman can match the apparition of his late wife, who visits him at intervals, offering a word of tenderness or advice. Her absence, and his yearning for her, form the emotional bedrock of the story, even though she too was a stranger when they stood under the chuppah, the wedding canopy, together. Both the son and the husband she left behind are floundering.

It’s clear that, in keeping with ultra-Orthodox custom, Shulem has many children and too many grandchildren to count. But narrative compactness demands that we see only a few. Akiva’s sister Giti spends the first season coping with the shaming truth that her husband, Lipa, has fled to Argentina, apparently discarding religious piety along the way. Giti remains strictly devout, as does her zealous daughter Ruchama. Meanwhile, her brother Zvi Arie studies hard but is frustrated in his ambition to head the yeshiva and, by the second season, is revealed as a man who had good reason to believe he would amount to more. Finally, there is Shulem’s aged mother, a resident of an old-age home where the default language is Yiddish. She is a human link with the European Jewish past and the vanished world it represents.

With the exception of Lipa’s short-lived sojourn in Latin America, which is never fully discussed—Giti would rather not know the details, so the audience never hears them—Shtisel declines to provide the stock storyline associated with religious characters in a drama: the crisis of faith. Even when Akiva gets a serious break as an artist, one which threatens to collide with his religious practice, he does not consider a life ungoverned by Torah. It is simply not an option. The Sopranos do crime, the Underwoods do politics, the Shtisels do God: that’s just how it is. It’s not up for negotiation.

It means that we see these lives from the inside. The gaze is not that of the secular outsider, looking upon exotic creatures whose return to normal, twenty-first-century life is surely only a matter of time. On the contrary, perhaps thanks to the guiding hand of co-creator Yehonatan Indursky, who was raised as a Haredi Jew, Shtisel seems to be telling the stories these characters would tell about themselves. There is no explaining (a scruple the Amazon version might struggle to observe), no serving up of comforting clichés for non-Haredi consumption.

Take Shulem Shtisel himself. A standard treatment would cast such a man—sixty-something, steeped in Torah and with the beard of a biblical prophet—as the sage patriarch, dispensing the wisdom of the ages. Shtisel does no such thing, daring to show Shulem’s naiveté, even his immaturity, allowing him to make a fool of himself with a younger woman, repeatedly issuing edicts to his children that are bound to be broken, and making all the wrong choices. He stops being the venerable ancient rabbi of Jewish kitsch and becomes a flawed—and therefore real—man.

But it is surely the romance that is most appealing. Thanks to the multiple restrictions, the firmly enforced rules and etiquette, the prohibition on even the mildest physical contact and, above all, the centrality and expectation of marriage, Shtisel plays out like a tale told by a Haredi Jane Austen, with sheitls, or wigs, for bonnets and peyot, or side curls, for cravats. There are the meddling parents, the yearning teenage girls, the elusive, uncertain bachelors, even a furtive love between cousins.

US audiences are used to such fare when it comes dressed as period drama, usually via Masterpiece Theatre, which has aired multiple Austen adaptations in recent years. Nevertheless, it might be jarring to see it played out in contemporary New York. Emmis will be a novelty: No Sex in the City.

That Shtisel exists at all is itself remarkable. Television is the terrain of secular Israel, which has long stood apart from the ultra-Orthodox Jews who make up just ten percent of the country’s population (but a third of Jerusalem’s). The relationship between the two has been one of mutual incomprehension, if not outright hostility. In Knesset elections in 2013, the second largest party was Yesh Atid (There is a Future), headed by the quintessentially secular figure of TV host Yair Lapid. That success was fuelled by Lapid’s pledge to end the exemption the Haredim enjoy from the military draft, a persistent source of secular resentment. (In September Israel’s supreme court ruled the exemption unconstitutional, sparking a potential political crisis.)

Advertisement

For their part, the Haredim have stood aloof from the state in which they live from the day of its founding in 1948. Many define themselves as either non- or anti-Zionist, for reasons of strict theology. They hold to the notion that the establishment of a Jewish state represents a blasphemous usurpation of divine authority: the Jews should have waited for the coming of the Messiah, and the resultant ingathering of the exiles to the land of Israel, rather than doing God’s work for him. This is the doctrinal basis that underpins Haredi refusal to serve in the military. Regardless of the theology, what many secular Israelis see is a community only too happy to stand under the national umbrella while declining to help hold it aloft.

This history is nodded to in Shtisel, but no more. In one episode Shulem is unsure whether to allow his young pupils to watch the flypast of Israeli Air Force jets that marks Independence Day. Surely the young boys should ignore such godlessness? In another, his brother Nuchem dismisses a slogan of official Israel. “Who wants to build a nation?” he asks. “Reshaim Arurim, damned evildoers.”

Perhaps, then, it’s no surprise that when the crew of Shtisel arrived in the ultra-Orthodox Jerusalem neighborhood of Mea She’arim for the first day of filming, they were chased out by a group of locals, outraged at the sight of a woman applying makeup to a male actor. After that, filming had to be done covertly, by a small, all-male crew dressed in ultra-Orthodox garb and using a hidden camera. According to The Forward, exterior scenes in the street were filmed from inside buildings, with each actor taking direction via an earpiece.

The casual viewer would have no idea. Indeed, it is a tribute to the quality of the acting that it is astonishing to discover that not one of the cast is, in fact, ultra-Orthodox. (There is a small Haredi film industry and there are Haredi actors, but they rarely appear in work produced by outsiders.) Dovel’e Glickman is so convincing as the hapless patriarch—from his Yiddish pronunciation to his gait—that few would guess that he was for twenty years the star of one of Israel’s favorite satirical TV shows. Kiva, the son, is played by the presenter of Israeli TV’s The Voice, a secular pinup rendered anew in peyot and tzitzit (the fringes on a prayer shawl).

The result is that Shtisel has had the unexpected effect of providing a small patch of common ground for two tribes that have long shared the same space but barely touched. It’s allowed chilonim, the nonreligious majority, to acquaint themselves with the lives of a community some might never encounter any other way. A smattering of Shtisel’s Yiddishisms have entered street-level, secular Hebrew—apparently “Reshaim Arurim” is a particular favorite of the Tel Aviv hipster set—while the show is said to enjoy an underground following in a Haredi world that, officially, eschews TV altogether. Downloads and DVDs reportedly change hands among ultra-Orthodox devotees. One unlikely proof that the show has penetrated previously impregnable Haredi culture is the emergence of the Shtisel theme tune as a favored melody at ultra-Orthodox weddings.

Perhaps one should not read too much into a single TV show, but it’s tempting to see Shtisel as achieving the kind of convergence, if not integration, that has tended to elude Israeli society itself. Shulem’s brother Nuchem, a schemer and businessman as worldly as Shulem is innocent, is played by Sasson Gabai, who was born in Baghdad. True, Gabai does not obviously look the part, but to see a Mizrachi, or Middle Eastern, actor play an Ashkenazi Jew, conducting long scenes in Yiddish, is to see what was once a sharp dividing line in Israel become blurred.

Perhaps even more striking is the name of the script editor for the second season. It is Sayed Kashua, the Palestinian novelist, screenwriter, and weekly columnist for Haaretz. When it comes to Palestinian citizens of Israel, Kashua is more the exception than the rule—he recently left Israel for Champaign, Illinois, where he teaches advanced Hebrew as well as TV comedy writing in the University of Illinois’s Jewish studies department—but still, the fact of it is remarkable: a dramatic exploration of ultra-Orthodox Jewish life, guided by a Palestinian Arab.

According to series co-creator Indursky, it’s a good fit. “You’d be surprised how much Haredim and Arabs have in common.” There’s something in that: Israeli demographers often link the two groups together, usually under the heading of “economically inactive.” Unemployment is an issue for both communities, especially among those Haredi men who either lack the secular education required for the workplace or else see it as their religious duty to study in the yeshiva rather than earn a living. Both communities, Haredi and Arab, exist on the edges of the dominant culture, which is secular and Jewish.

In one way, then, both the team behind Shtisel and the range of its audience suggest a vision of Israel far less balkanized than the picture conveyed on screen. For what the viewer sees is a community all but sealed off from the society that surrounds it. When secular characters appear—such as Kaufman, the gallery owner who takes Akiva under his wing—they look alien, even odd. The viewer begins to see the world through Haredi eyes. (As for Israel’s Arab minority, and the Palestinians of the occupied territories, they are barely mentioned. They might as well not exist. Which is probably an accurate, if disheartening, reflection of Haredi life.)

But if this simple act of humanizing Haredi Jews for a secular Jewish audience is a milestone for Israel, given the sullen misapprehension that has long existed between the two groups, then it represents an even greater shift for Zionism. For the founding ideology of Jewish nationhood was, implicitly and sometimes explicitly, hostile to the strictest strands of Judaism.

It wasn’t just the doctrinal dispute over the legitimacy of auto-emancipation, of Jews liberating themselves without divine assistance. There was something deeper too. The first Zionists believed they were restoring the Jews to their rightful place as a nation rather than merely a religious faith. To them, ultra-Orthodox Jews represented an earlier stage of evolution, one which it was the Jewish destiny to leave behind.

What’s more, in the Zionist imagination the Haredi stood as a kind of uber–diaspora Jew. He was the galut, the exile, in human form. He was pale, introverted and buried in books, while Zionism was committed to a form of Muskeljudentum, a muscular Judaism that would raise a new Jew: tanned, strong, working the land and gazing toward the horizon. The Zionist pioneers were confident that the orthodoxy of the shtetl, its rituals and superstitions, would fade away once the Jews became what they deemed a normal people, healthy and rooted in a land of their own. Muttering, murmuring Yiddish would die out, replaced by a renascent, earthy Hebrew.

So the ironies are many in an Israeli television show that depicts Haredi life with dignity and injects Yiddish into the national bloodstream. Shtisel was not what the bulk of Israel’s founding generation had in mind. And yet it can also be read as a consequence, albeit an unintended one, of Zionism. For it is just the kind of flowering, the fruit of a vibrant Jewish culture, that a Zionist like, say, the essayist Ahad Ha’am (1856–1927) believed could only spring from the creation of a new society. Even if most of the country’s founders would have imagined Israel without Shtisel, it’s hard to imagine Shtisel without Israel.

And yet none of this is what gives the show its strength. Shtisel is drama, not anthropology. Its power comes from its keen, forgiving eye for human foibles and weaknesses: parents projecting their own pain onto their children, daughters who cannot forgive their fathers, husbands seeking the love of their wives. There is humor. “May you swallow an umbrella that opens inside you,” says Nuchem, deploying a hoary Yiddish curse. “Come on,” says a would-be bride to Shulem, waiting for his proposal. “We’ve met five times already. What are we, modern Orthodox?” There is pathos. “Let me die like a rebbetzin,” pleads a previously mean-spirited widow of a rabbi in the old age home, as she chooses to end her own life rather than decay through illness. And there is insight into human beings, struggling to make their way in a universe that can seem harsh and full of sorrow—even to those who believe it was created by God Almighty.

This Issue

February 8, 2018

To Be, or Not to Be

Female Trouble

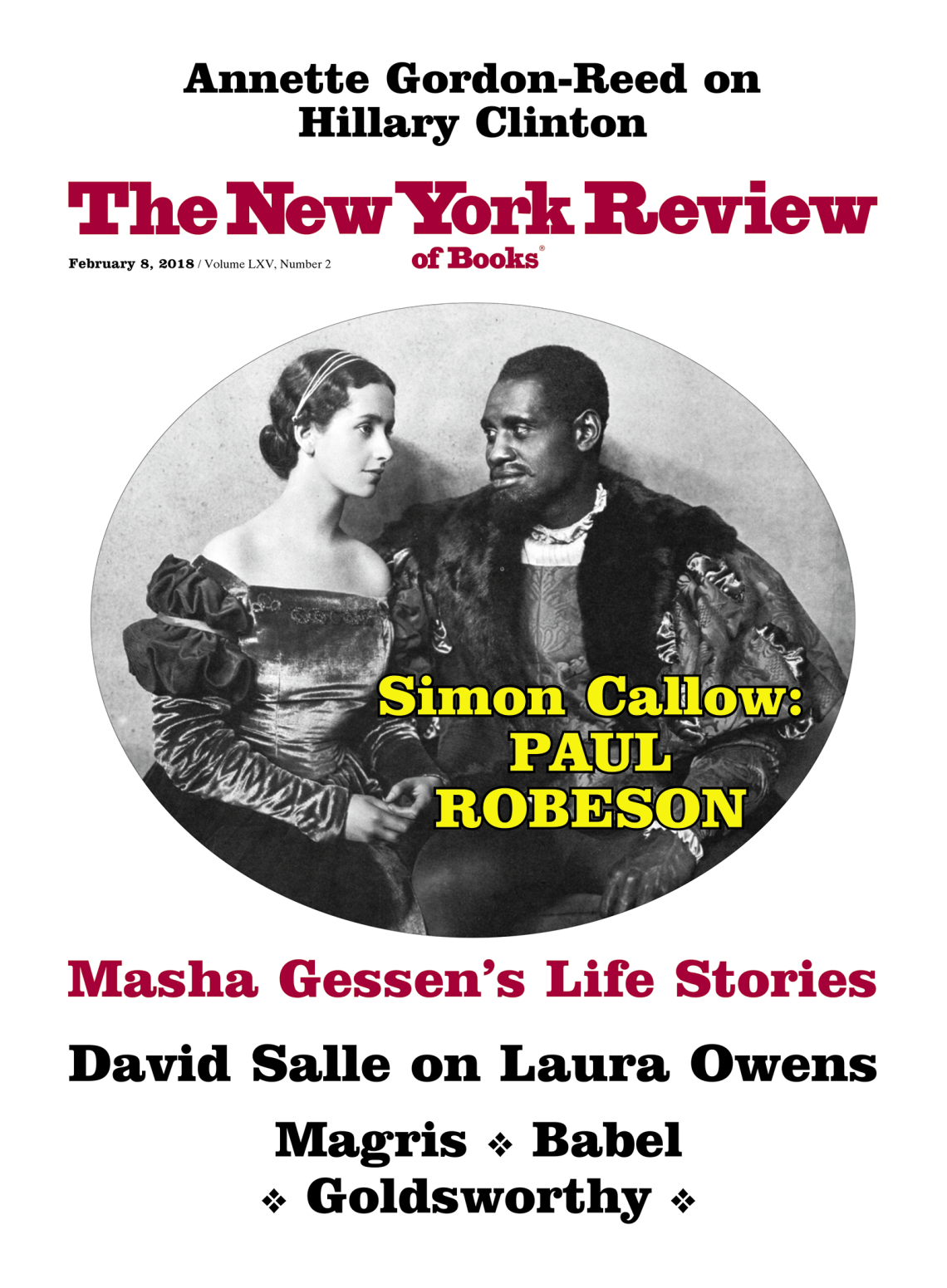

The Emperor Robeson