1.

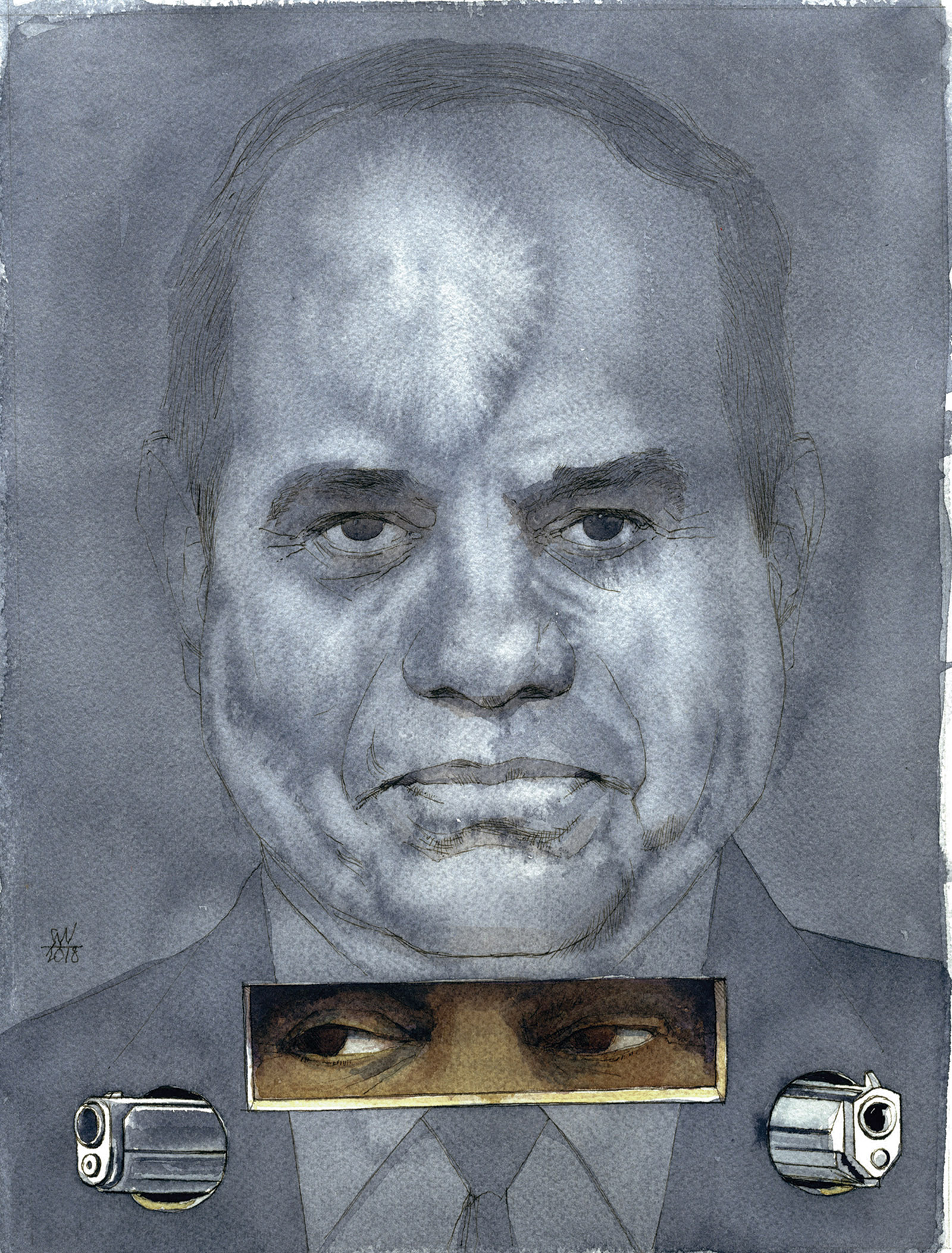

I admit that when I began these notes in the autumn of 2014, some six months after the election of Egyptian president Abdel Fattah el-Sisi the previous May, I wanted to build a case in support of el shaab (the people). By that I mean the unprecedented number of Egyptians who had taken to the streets the summer before, calling for the army to assist in the ouster of then president Mohamed Morsi. The grievances against the Islamist president were many, including violence perpetrated by his Freedom and Justice Party and the most overreaching power grab of any Egyptian president (he granted himself extrajudicial constitutional powers). Amid a rapidly declining economy and a general sense of disarray, popular dissent had escalated. Millions of Egyptians poured into the streets, underhandedly encouraged by long-standing forces of the “deep state”—the army and state security services.

In the months following Morsi’s removal by the military in July 2013, described nationally as “the second revolution” and internationally as “a military coup,” I kept a notebook of the varying descriptions of Egyptians in the international press. They were criticized for their call to topple a freely and fairly elected leader. The question of morals and ideals recurred. Mention was even made of abandoning “morality” for short-term political gains.

Although I understood that my circumstances were particular, as well as privileged—from the neighborhood I lived in to the school I went to—I was not so naive as to think that military rule would not infringe on my life. There were many precedents in our history: crackdowns on activists, newspaper editors, writers, and “debauchery,” which is legally defined here as anything that falls outside marital bounds. The last of these has been a witch-hunt. I convinced myself that lives like mine were peripheral to a nascent political discourse. Setting out to defend the actions and choices of the beleaguered working class seemed virtuous. I realized only later that these different sets of interests—of personal and political freedoms, and basic standards of living—were all inseparable.

2.

In search of my story, I got in my car and drove east in mid-May 2015 from Cairo to Suez. Nine months earlier, Sisi had announced the revival of a decades-old “mega-project” to expand the 150-year-old Suez Canal. He pledged that the project would be finished in exactly twelve months, and that every Egyptian would see “immediate returns.” I was skeptical about the promised date of completion and drove through the desert to see for myself. Celebratory billboards lined the route leading out of the city, as if the project was already complete. At the site of construction, I was told that the army had been working round the clock.

The new canal was in fact inaugurated on August 6, 2015, twelve months to the day from when the project was first announced, and thousands of Egyptians took to the streets in celebration. Downtown Cairo was awash in flags and fireworks, music, flashing strobe-light shows, and animal-themed blow-up dolls as tall as townhouses whose only visible relationship to the canal might have been symbolic, in their exaggerated size. It brought back memories of the day in February 2011 when President Hosni Mubarak stepped down.

Acting as a government mouthpiece, the local press described the New Suez Canal as “Egypt’s gift to the world” and “the great Egyptian dream.” The foreign press generally referred to the “$8 billion Suez Canal expansion that the world may not need.” A former ship captain explained to me: “Eight percent of global sea trade currently passes through the Suez Canal. By multiplying capacity, you’re multiplying the number of ships that will save the extra ten days and 9,000 kilometers that it takes to sail around the Cape of Good Hope.” If a 35-kilometer portion of the 164-kilometer artificial waterway that connects the Mediterranean to the Red Sea were expanded to make a two-way channel, the eleven-hour wait time of ships passing through would be reduced to three. Seventy-four more ships could pass through the canal each day. Annual canal revenue would double by 2023.

The financing of the project under Sisi was shrewd—a tax-free public bond with certificates in denominations as low as ten Egyptian pounds (marketed to students), and a 12 percent interest rate with the option of quarterly payouts. The necessary $8 billion was raised in a week. People everywhere spoke of having put their savings into Suez Canal bonds. Lives felt quantifiably changed—I heard references to “free money.”

In that same inaugural summer, France sold Egypt twenty-four Rafale fighter jets, some of which flew over the city on a Friday in July, rattling windows and roaring into the lull of a blistering afternoon during Ramadan. Someone on Twitter called the air show “juvenile,” and a stream of snide remarks in English followed, but as the planes flew overhead, I watched people who were waiting for the bus downtown burst into applause. It was the same reaction I had seen months earlier when shiny new black, armed police jeeps began to circulate in the streets of the city, sirens sounding, back windows open, masked men with guns peering out. It was, when I thought of it, directly linked to the illusion of safety. After the turmoil of recent years, it was about a tangible measure of change.

Advertisement

What strikes me most vividly about that time is the discrepancy between what I was experiencing on the streets and the narratives I was reading on social media and in the international press. This, I realized, was the critical distance between emotion and intellect, between the democratic ideals of what a place should be and the symbolic changes that have no significant impact on the quality of everyday life but cause a palpable emotional effect in people.

3.

Later that year, in the fall of 2015, while I was having breakfast with my father and his friends at the local sporting club, debating the worsening condition of human rights, a young waiter who was friendly with my father excused himself for interjecting and said, “Sorry to contradict you, but human rights begin with the conditions under which we live. The revolution made life harder for us—us being the poor—so of course when they arrest these activists, I say it’s for the better, we can’t afford another revolution. We can hardly afford to eat each day.” I asked the waiter about his salary (200 pounds a month, then about $25), and whether he had been to Tahrir and supported the protests in 2011. “Of course,” he replied, “like everyone, I wanted a better quality of life.”

By then it was December, four months after the opening of the new canal, and, aside from those who had bought bonds and received the first payout, most people I heard began describing it as el-tira’a (a sewer). When I asked one woman, Sabah, a cook who juggles jobs in six homes each week, why her opinion of the canal had changed, she said: “They promised revenues and immediate returns, and now everyone says revenues are down. Where are the immediate returns? The project has failed.”

The success of Sisi and his government had quickly come to be measured by the concrete effects their symbolic gestures had on daily life. The canal, four months later, was a failure against the measure of “immediate returns,” but the president, as yet, was not. For those like Sabah, her income and residential address had entitled her to government assistance. Sisi reimplemented this program, along with others adapted from the Nasser days, but now with a much higher monthly allowance for each eligible family, and no longer limited to cooking oil and sugar. Sabah’s new monthly allowance for her family of five stood at four kilograms of meat, 100 rolls of bread, a bag of oranges, three kilos of tomatoes, two packets of sugar, two bottles of oil, a sack of rice, and access to a range of government-subsidized goods (garbage bags, soap, canned products, fresh vegetables, frozen chicken).

This, she said, if one were to be “fair” and “despite the failure of the canal,” had to be acknowledged as one of the “great successes” of Sisi’s year in office. At a government-subsidized co-op, people told me that by today’s standards these supplies were “as good as free.” They also reminded me about the increases in state salaries, the exemption from public school fees that year, the implementation of the Dignity welfare cash program for the elderly and disabled, and the 15 percent increases in state pensions; one woman tapped on my notebook insistently and asked me to write that down.

Yet later in the winter, there was a sense of disappointment—a gap between the expectations of what a president could accomplish immediately and what had actually materialized. Experienced through the glaring lens of the past six years, however, Sisi was still seen as “the savior.” “His intentions are good,” people would say, “his heart is with the country.” Sisi was no Nasser, but his nationalist credentials as a former army general lent him credibility. He also spoke the language of the street—his public speeches were matter-of-fact and colloquial.

4.

I spent the remainder of the winter and the spring of 2016 away, in New York on a fellowship, following the news in detail from afar. I conducted interviews by Viber and by proxy, taking notes as I tried to keep up with events at home. Discontent surged in February over the shifting official accounts of what had happened to Giulio Regeni, an Italian graduate student who disappeared and was then found dead on a highway in Cairo, his body bearing marks of severe torture. Everyone I spoke to expressed outrage and disbelief. Diplomatic relations between Italy and Egypt were threatened, and rumors were circulating that Regeni had been killed by the police to undermine military intelligence and the army. A former parliamentarian told me at the time that the murder might have been a mistake—torture gone too far—but that “there are deep tensions between the two factions of intelligence in the country, and it puts the country at some peril.”

Advertisement

Regeni’s murder extended beyond the bounds of what we had come to expect from even the most brutal of interrogations, and friends talked about it for months afterward. Then in April, the president declared that two Red Sea islands, Tiran and Sanafir, long perceived as Egypt’s, fell within the territorial waters of Saudi Arabia and would be transferred to the kingdom. Public attention shifted to this new declaration, which brought revolutionary and pro-government Egyptians together in opposition to it. The handover hit a deep nationalistic nerve—it was seen as a “selling out” that undermined Egypt’s sovereignty—and Egypt’s courts halted it, overruling Sisi, who eventually overruled them. There were murmurs of another revolution and scattered small-scale protests. Over 150 protesters were arrested and jailed. But revolutionary sentiment then ebbed sharply in May, when an EgyptAir flight from Paris crashed into the Mediterranean, killing all sixty-six people on board and stirring pity among Egyptians for their country and its government.

When I returned home to Cairo in June, there was a general sense of calm, and as I tended to paperwork at the government’s central administrative building over the summer, I asked the several dozen clerks who handled my papers about the general state of things. When I asked about inflation and the cost of living, they would shake their heads, but thank God we can still put food on our tables. What about the shortages of certain food supplies? Thank God the army is stepping in and providing them. And the battle over the dam being built by Ethiopia that will threaten Egypt’s water supply? It would be a catastrophe, but thank God Sisi is a statesman.

I might have asked: What about the shutting down of publishing houses and cultural spaces? What about the activists in jail? What about the prison sentences handed out en masse? What about the TV programs banned and anchors taken permanently off the air? What about the $45 billion being spent on “The New Capital,” another mega-project, which will relocate the capital from Cairo to a “smart hub” being built in the desert? This last one was met with muffled grumbles, but the answers to the others were invariably: “The government’s job is to keep us fed, and at least the country is safe again.” The violent tumult of the jihadi stronghold in Sinai was far enough from the everyday life of the city that it hardly figured into this feeling of safety; it did, however, justify for people the extreme crackdown on Islamists. (TV anchors regularly lamented attacks on conscripts in the Sinai and spoke of “Egypt’s war on terror.”)

More and more, on the streets of Cairo, in government offices, and in informal settlements on the outskirts of the city, I heard references to Syria: “We could have ended up like them.” Disappointment seemed to be bracketed by this comparison. Islamist supporters with whom I had long-standing relations were harder to engage; those I did get through to generally shook their heads, shrugged, and said there was “nothing to say.”

Egyptians were commonly criticized as “apathetic” or “inert,” but they might more accurately have been described as “passive.” Government employees, people tending to their lives, those who spoke and those who did not—all were making a calculated choice. Passivity has been their particular mode of survival.

This same passive disposition had come to mark many of the rest of us too—activists, intellectuals, and people on the left. I kept tabs on the shrinking number of people who showed up to protest, and then on the decreasing number of protests. Only a handful of people still voiced their dissent, including Laila Soueif, the matriarch of a family of longtime activists, whose son Alaa Abdel Fattah is serving a five-year prison sentence on trumped-up charges; or the team behind the online paper Mada Masr, led by the journalist and editor Lina Attalah, who continued to publish despite scrutiny and censorship (the paper’s website was eventually blocked, along with 127 others). The risks of human rights work had become almost prohibitive, with arrests, disappearances, and travel bans all commonplace. I counted the number of activists, academics, and artists who had left the country, and friends who were emigrating. Regeni’s name often came up in conversations—his murder lingered in our minds.

More and more of my friends and acquaintances were expressing discomfort, even fear, over the punitive and increasingly severe measures taken by the state. A friend’s activist neighbor was dragged from his home in the night and disappeared for four days on allegations of being an “Islamist sympathizer” (he was not); a writer was imprisoned, on grounds of “offending public morals,” for sexually explicit scenes in a novel; gay men were being hunted by undercover police on the hookup app Grindr; a poet was jailed on charges of “blasphemy” and “contempt of religion” for calling the slaughter of sheep during a Muslim feast “the most horrible massacre committed by humans”; two women were threatened with jail for allegedly “kissing” in a car (they were not). It was around this time that I started to become conscious of what I kept on my phone and downloaded a virtual private network to divert my Web presence from Cairo to Italy.

I also observed, in myself and my friends, how inured we had become to the events of our own recent history, which were landmarked by the sites where they had occurred: this was where the Copts got trampled by army tanks; on this street corner I saw a pile of dead bodies; here supporters of Morsi opened fire on young activists; there two hundred people were killed at the hands of the police; and this was where the prosecutor general was assassinated by a car bomb. It was only as I made these mental notes that I realized how I, too, had slipped into some variation of the so-called inertia. A friend one evening described our often-dulled responses to news and events that once enraged us as a type of PTSD.

5.

If there was a logic to the emotional and practical calculus that kept dissent at bay during the first two years of Sisi’s presidency, it was widely thought that the events of November 2016 might undermine his rule. As a result of severely dwindling currency reserves, the government was forced to implement a series of long-overdue austerity measures to secure a $12 billion loan from the IMF. The risks of implementing the loan program were described by the agency’s staff as “significant.” Morsi had considered these same measures but backed out after a public outcry. Sisi had little choice but to take the risk. First gas and fuel subsidies were suddenly lifted (causing price hikes of 50 percent), then the Egyptian pound was floated, plunging the currency from seven to twenty pounds against the dollar. Overnight, the price of milk, tomatoes, pasta, cigarettes, soap, water, sugar, oil, chicken, chocolate, bread, juice, toilet paper, matches, bananas, plumbing services, and household goods leapt.

I heard people complain that their businesses lost half their value; a cargo expediter said everyone was affected by the crisis except the one percent. A friend with a medium-sized business importing knickknacks from China said he was thrust into sudden debt. Many months later, when summer approached, I asked him what he now thought of the austerity measures, which had already driven up foreign direct investment. He replied: “Don’t talk to me about politics. The only thing I can talk about is making enough of a living to put my kids through school and pay for the bills, which I barely can. They want to make it impossible for us to be political.”

I thought about this when I went to a popular nightspot downtown guarded by hefty bouncers. Once inside (for $3), I watched a younger generation of friends, who have drifted in and out of depression the past few years, order rounds of beers on the dance floor. I attended house parties where those same friends shared stories about other parties of Sixties-style drug-fueled “debauchery.” I asked these friends, who had all come of age during the revolution, whether they weren’t scared. “It’s the only way to survive,” a friend who is a DJ told me. “Either you indulge fully and get lost in this hedonistic lifestyle, or you die.”

As prices increased further, I wondered how anyone would be able to survive. My mother complained about the cost of basic goods and monthly expenses, and friends snapped as their electricity bills rose to many times what they used to be. By August, I heard people everywhere talking about the price of school supplies. School bags seemed to be the measure of the state of things. What cost 90 pounds a year before cost 350 pounds now. Inflation was at its highest (33 percent) since 1986 (when it was 35.1 percent), and second-highest since 1958. When, over the months that followed, I asked my grocer or the man who delivered the bread or the garbage collectors how they were managing to keep afloat, the invariable answer was “baraka”—blessings from God.

I asked Sabah again, last October, what she thought of the situation. The voucher the government offered her for food supplies used to cover her family’s needs, but now covered a fraction of them. Free money and “as good as free” goods seemed as far gone as revolution. So had Sisi failed her? “They say he is building a $10 million palace in the desert for himself when the rest of us can hardly eat, but what is the alternative? To be fair, he inherited a mess. At least he is a nationalist, one of us.”

6.

When Sisi took office in May 2014, little was demanded of him by those who took to the streets except to rid the country of the prospect of a revived Islamic caliphate. The eradication of rising Islamist views was widely supported, even by the president’s fiercest critics. Last summer, Mohamed Anwar Al-Sadat, founder of the Reform and Development Party, the former chair of the parliament’s Human Rights Committee, and the nephew of former president Anwar Al-Sadat, told me: “We would have descended into chaos had the Brotherhood stayed in power. The country would not have survived the remainder of Morsi’s term.”

There was a handful of people who knew what military rule would bring, who anticipated the crackdowns, the closing-in of the state. Some had forecast the outbursts of violence to come. But perhaps nobody quite anticipated that the deep state would be resurrected with such ferocity, and so unabashedly. As I went about my days last summer, I saw plainclothes state security informants on every other street corner and in almost every café. Twice in the course of a week they circulated through the streets of my neighborhood, taking inventories of everyone living or working there or visiting the area, and copying IDs. At a gallery downtown that I frequently visit, there was a resident informer seated across the street every day. When I asked a range of political figures about the surveillance, the answer I got was “paranoia”—to this day, no one fully understands the political and emotional causes that led to the revolution on January 25, 2011.

Last summer, in his sprawling office near the presidential palace, Al-Sadat told me that he had urged Sisi to consider a more pluralistic approach to governance. “You can’t annihilate an entire group. History has already tried and failed with that.” And Sisi’s response? “None. And I fear that if they continue this way, you will start to hear of school buses and cinemas being bombed. We’re on that path.” A suicide bomber who blew up a Coptic church in Alexandria last April had allegedly been held in an Egyptian jail for the preceding two years. In late November, 305 people were killed in an Islamist shoot-out in a mosque in Sinai. And yet tourism in Cairo has been increasing—I saw busloads of foreigners at the Egyptian Museum last summer; a year before, there had been none. People I speak to criticize Sisi for keeping the interior minister in office despite terrorist attacks. At the same time they express pity for the army—radicalism seems at once to undermine and to strengthen Sisi’s hold on power. The country feels more and more mired in such contradictions.

Al-Sadat, who was kicked out of parliament for criticizing the government’s human rights record, had considered a presidential run this March but now says he won’t compete for fear of retribution against his supporters in opposing Sisi. Ahmed Shafik—who lost closely to Morsi—has also backed out, his lawyer citing intimidation by the state. The young leftist lawyer and activist Khaled Ali, who took less than 2 percent of the vote in 2012, was expected to run again, but he withdrew, saying that “conditions do not allow for a fair contest.” Also running was the army’s former chief of staff, Sami Anan, before he was detained for questioning on grounds of breaching military law. The rest of the political opposition is fragmented, worn down by a lack of organization and the turmoil of the past few years (many leading political figures are living abroad, in exile).

There are many questions at this point. The most immediate is less about who will win than about who will run and what they might inspire. Can we find meaning in being engaged again, lining up for hours as we did when we went out to vote—in most cases for the first time in our lives—after Mubarak was ousted in 2011?

“I admit,” a brass worker in Cairo’s old city told me one evening in November, “I’m not happy with how things have unfolded. This was never a revolution to begin with. It was all scripted from the start, by military intelligence, so what is one to do now except put your head down and try to make a living?”

—January 25, 2018

This Issue

February 22, 2018

God’s Own Music

The Heart of Conrad

Doing the New York Hustle