On January 10, The Washington Post reported that Donald J. Trump passed a milestone that none of his predecessors is known to have attained: just short of the anniversary of his first year in office, he told his two thousandth lie.1 It had happened sometime the day before, when the president was meeting with legislators to discuss immigration and tossed out a few of his old standbys—about how quickly the border wall could be built, about “the worst of the worst” gaining entry to the United States through a visa lottery, and about his wall’s ability to curtail the drug trade.

The path from the first lie to the two thousandth (and now beyond), a veritable Via Dolorosa of civic corruption, has been impossible for even the most resolute citizen to avoid. Trump is in our faces, and our brains, constantly. Yet the barrage is so unceasing that we can’t remember what he did and said last week, or sometimes even yesterday. Do you remember, for example, that first major lie? It was a doozy: the one about how his inaugural crowds were larger than Barack Obama’s, larger than anyone’s, the largest ever, despite the ample photographic evidence that rendered the claim laughable.

That was Day One. On Day Two, he sent his press secretary, Sean Spicer, out to meet the White House press corps for the first time. In that ill-fitting suit jacket that appeared to have been tailored for someone with a neck a good three inches thicker than his, Spicer insisted that the photographs were misleading and the press was wrong. Not just wrong—lying. “There’s been a lot of talk in the media about the responsibility to hold Donald Trump accountable,” he said, sputtering his words in terse reports as if they were issuing from a machine gun.

And I’m here to tell you that it goes two ways. We’re gonna hold the press accountable as well. The American people deserve better, and as long as he serves as the messenger for this incredible movement, he will take his message directly to the American people, where his focus will always be.

Here we are, a year later. From my reading and television viewing, the general assessment of most pundits seems to be that it’s been worse than we could have imagined (except on the Fox News Channel, where everything in Trump world is coming up roses and the gravest threat to democracy is still someone named Clinton). But honestly, who couldn’t have imagined any of this? To anyone who had the right read on Trump’s personality—the vanity, the insecurity, the contempt for knowledge, the addiction to chaos—nothing that’s happened has been surprising in the least.

I think most close observers of Trump understood his personality perfectly well. If that’s right, what, then, could explain the surprise? Maybe just a reasonable disbelief that a president would, for example, remark crudely on a female television anchor’s facelift surgery, or actually encourage the Boy Scouts—the Boy Scouts!—to boo his predecessor (remember that one?). But I think there has been some deeper collective refusal on the part of the political class to acknowledge what has happened here, and of course to own up to their part in it. No one (on this point I include myself) believed Trump could win. No one took his candidacy seriously enough. This is especially true of the press, which, in hammering away on Hillary Clinton’s e-mails, assumed itself to be in training to refight the wars of the 1990s once the Clintons moved back into the White House.

When we are forced to confront the reality of a shocking outcome that we never thought would happen, we start rationalizing: It wasn’t our fault. There’s nothing we could have done. Maybe it won’t be so bad. Maybe it’s what we deserve. And maybe, in some strange way, it will all work out.

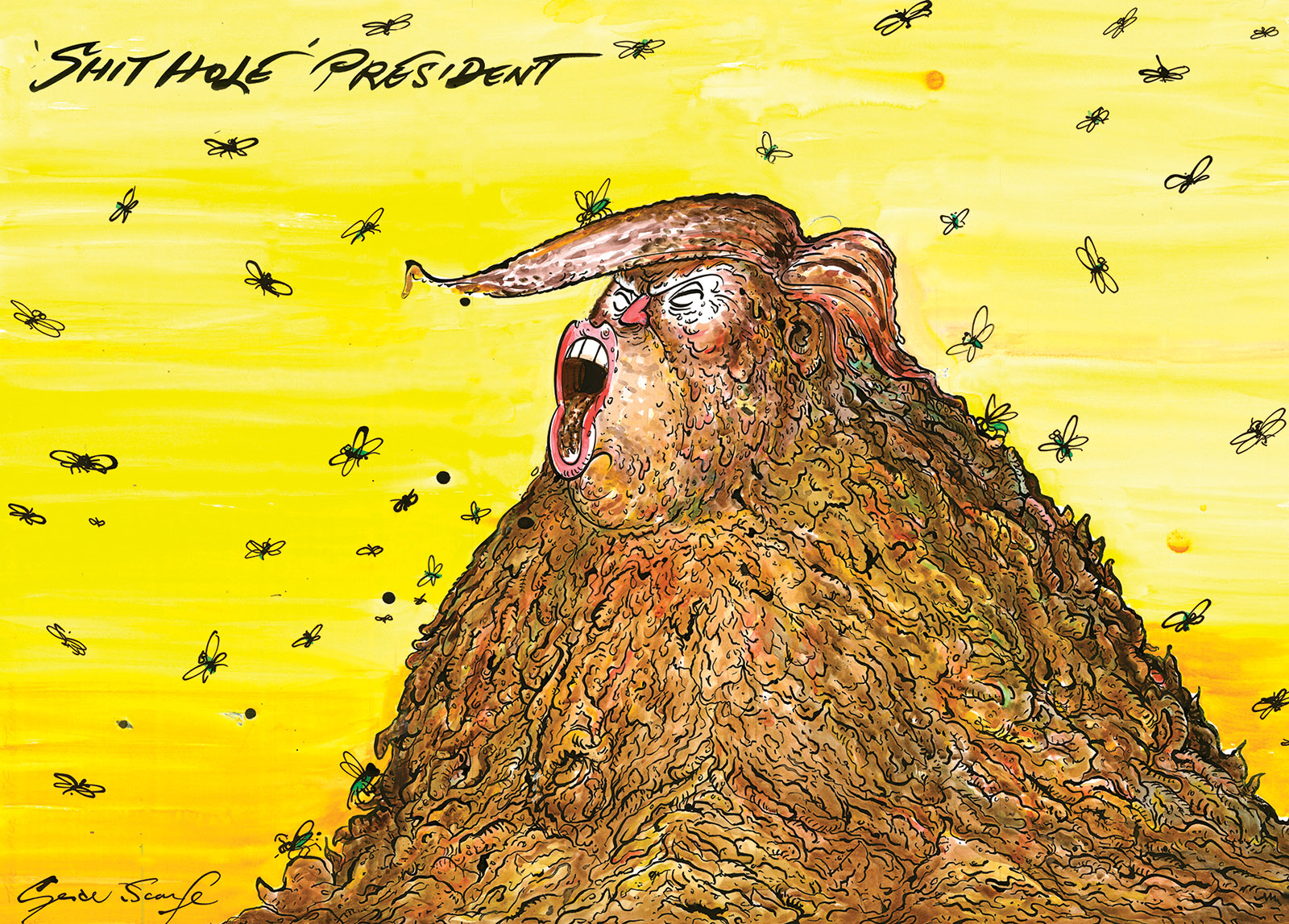

To be fair to the press, the reporting on the Trump administration has been thorough and often unflinching, willing to call a lie a lie (witness the Post’s list) and even resolved, as we saw recently, to print the word “shithole” in news stories and headlines and say it on air. But the rules of journalism generally prevent news outlets from rendering larger judgments. Journalism tries to get the little stuff right but often gets the big stuff wrong.

Enter Michael Wolff.

For a good two decades, Wolff has chronicled the doings of important people—in media, mostly, but also in Silicon Valley and show business and politics. His subject is power and how men (and some women) use it. We were colleagues for a few years at New York magazine. We talked politics sometimes, but he was always rather sphinxlike on the topic. I suppose if one sat him down and asked him his positions on abortion rights and same-sex marriage and global warming and so on, he’d come out a liberal. But positions per se don’t interest him much. What interests him is how men to whom history has given the stage command it or fail to.

Advertisement

Wolff interviewed Trump in the spring of 2016 for The Hollywood Reporter, his current home base. When the resulting piece—not fawning, but by no means written with the acid pen for which he is often known—appeared, he e-mailed Trump press aide Hope Hicks. Her oh-so-very Trumpland verdict: “Great cover!” (It featured a grainy shot of Trump’s head floating in air, with images of Hillary Clinton and Bernie Sanders in his mirrored sunglasses.) Wolff then approached Trump after the election, as he wrote in the Reporter following Fire and Fury’s release, with an offer:

I proposed to him that I come to the White House and report an inside story for later publication—journalistically, as a fly on the wall—which he seemed to misconstrue as a request for a job. No, I said. I’d like to just watch and write a book. “A book?” he responded, losing interest. “I hear a lot of people want to write books,” he added, clearly not understanding why anybody would. “Do you know Ed Klein?”—author of several virulently anti-Hillary books. “Great guy. I think he should write a book about me.” But sure, Trump seemed to say, knock yourself out.2

In an in-house interview with a Reporter staffer timed to the book’s release, Wolff confirmed that politics and ideology weren’t exactly foremost in his mind. He was asked whether he had been “just a neutral observer” in the White House:

Completely. I would have been perfectly happy to have written a contrarian book about how interesting and potentially hopeful and novel Trump-as-president was. I would have written a positive Trump book. And I thought it would be a fun thing to do—an audacious way to look at the world.3

And so Wolff got his access, as he wrote in his own Reporter piece, because Trump’s “non-disapproval became a kind of passport for me to hang around.” He benefited, no doubt, from the unprecedented disorganization of the Trump White House, where no one quite had the authority to tell him to leave. He made his appointments, but basically, he says, he just plopped himself down on a couch in the entrance foyer of the West Wing. I know the anteroom, and the couch. The Cabinet Room is to the left as you face the sofa (with the Oval Office off of it), the Roosevelt Room to the right, and many offices nearby. Everyone walks by. It’s a grand place to sit and watch.

In no time, he was horrified at what he saw. You surely know by now the book’s big scoops, which are stunning. The biggest one is dropped very late in the book, in a section about Trump’s sons, Don Jr. and Eric, who “existed in an enforced infantile relationship to their father, a role that embarrassed them, but one that they also professionally embraced.” Wolff is discussing the infamous meeting on June 9, 2016, at Trump Tower that Don Jr. had with Paul Manafort—who would soon be named Trump’s campaign chairman—Jared Kushner, and the Kremlin-connected Russian attorney Natalia Veselnitskaya.4 The New York Times broke the news of the meeting last July, and sources told the paper that Don Jr. was looking for dirt on Clinton.

Wolff writes that “not long after the meeting was revealed,” he was talking with Steve Bannon, then still the president’s chief political strategist, who said: “Even if you thought that this was not treasonous, or unpatriotic, or bad shit, and I happen to think it’s all of that, you should have called the FBI immediately.” It was this quote—far too frank, and given to “the enemy,” i.e., the nonconservative media—that got Bannon fired from Breitbart News, to which he had returned after he left the White House (and where, incidentally, he was earning $750,000 a year in 2013, which was at least $200,000 more than Jill Abramson, the editor of The New York Times at the time, was making). The quote has landed Bannon in the conservative movement doghouse, but we all know these things can change; it’s not hard to imagine the mercurial Trump deciding someday that Bannon is of use to him again.

That quote was hard news, but the most breathtaking scoops in Fire and Fury are about Trump himself. “What a fucking idiot,” Rupert Murdoch is reported to have muttered as he put down the phone after talking to Trump, then president-elect, about immigration. Trump’s complete incuriosity and resistance to learning anything is a constant theme. “Here’s the deal,” one of Trump’s close associates told Reince Priebus, when the former Republican Party chairman was named the president’s chief of staff. “In an hour meeting with him you’re going to hear fifty-four minutes of stories and they’re going to be the same stories over and over again. So you have to have one point to make and you have to pepper it in whenever you can.”

Advertisement

The White House and the GOP, of course, have tried to attack Wolff’s credibility. Trump himself, on January 13, called Wolff “mentally deranged” in a tweet (his first public remarks that day, after he finished the round of golf he was playing when Hawaii received a false missile attack alert). Even presumably sympathetic interlocutors like Stephen Colbert have pressed Wolff on why he doesn’t make public the recordings of these conversations he says he has. And some journalists have spotted small mistakes, like a Washington Post reporter placed at a meeting he apparently did not attend.

But by and large, Wolff’s reporting has held up. It makes perfect sense that Trump not only didn’t expect to win, he didn’t want to win. By the end he campaigned feverishly, because he’s a competitive man, and he surely hated the thought of losing, as he would have put it, to a girl. But he did not want to be the president:

He would come out of this campaign, Trump assured [Roger] Ailes, with a far more powerful brand and untold opportunities. “This is bigger than I ever dreamed of,” he told Ailes in a conversation a week before the election. “I don’t think about losing because it isn’t losing. We’ve totally won.” What’s more, he was already laying down his public response to losing the election: It was stolen!

On election night, when it became clear that he had won, Trump, Wolff writes, seemed paralyzed. Melania, his wife, was crying, and not tears of joy.

The attacks on Wolff haven’t stuck partly because it all rings so true. But I think there is also another reason. Some critics have tried to accuse Wolff of not playing by the standard rules of journalism, by which they mean to insinuate that he’s taken off-the-record material and put it on the record. But no one has produced evidence of this. And in fact, outside of eight or ten salacious quotes, nothing in Fire and Fury seems out of the ordinary. Indeed, for quite long stretches, it reads like any conventional work in the genre. Trump himself disappears for pages at a time. The running theme is the feud between Bannon and “Jarvanka,” Wolff’s portmanteau for Jared Kushner and Ivanka Trump, which is no more inherently interesting than the feuds inside any other White House. At times one can feel Wolff himself getting a little bored.

However, there is one sense in which he doesn’t play by the usual rules. Wolff doesn’t do “fairness.” He comes to his conclusions, and he lets you know them. He doesn’t tell the other side. No New York Times or Washington Post reporter could have written this book. They follow rules that demand more “balance,” rules under which they might have been more likely to get all the small things absolutely right but would have diluted the larger truth. And so, free from that stricture of straight news reporting, Fire and Fury has performed a great public service: it has forced mainstream Washington to confront and discuss the core issue of this presidency, which is the president’s fitness for office.

While Wolff doesn’t emphasize policy positions, they are of keen interest to David Frum, the conservative commentator who writes for The Atlantic and graces cable-news television screens frequently, often these days in need of a shave. For many years, Frum has been an astute observer of the conservative movement. It is a measure of how conservatism has changed—and possibly of how Frum has changed, but I think more the former—that he used to write books and articles criticizing the Republican Party from the right. His 1994 book, Dead Right, argued that Republicans had drifted from their ideological roots of minimal government, fiscal responsibility, and personal probity. From today’s vantage point, of course, the concept of drift circa 1994 seems quaint.

Today Frum—also a onetime colleague of mine, at The Daily Beast—is part of a group of (former?) neoconservatives who have emerged as some of Trump and Trumpism’s most forceful critics. It seems likely, in the first instance, that their objections to Trump had to do with his Lindberghian foreign-policy views, which offend everything they have stood for. Back in late 2015, neoconservative criticisms of Trump tended to be focused on his isolationism. But in fairness, their attacks on him have expanded far afield from foreign policy, to his rhetoric and behavior and destruction of norms and all the things liberals care about.

Weekly Standard editor Bill Kristol was a neoconservative writer, organizer, and theorist for a quarter-century, at the barricades on controversies from health care reform to the Iraq War (he was also the most important promoter of Sarah Palin, who embodied Trumpism before Trump became Trump). Now he regularly issues withering tweets about Trump and is a fixture on the liberal-leaning MSNBC. The foreign policy writer Max Boot was a vocal and at times strident champion of the Bush Doctrine. These days he’s a ferocious and shrewd critic of the president. Washington Post blogger-columnist Jennifer Rubin was, among prominent conservative pundits, probably Mitt Romney’s most aggressive defender in 2012 and aside from that was known for her hard-line foreign policy views, particularly on matters relating to Israel. Now, her columns often read as if they could have been written by the late Molly Ivins. (Two recent Rubin headlines: “Trump Retreats on Iran, and He Will Need to Do So Again”; “The Enablers of the Racist President Are Back at It.”)

Observing the extent to which the Trump era has forced these and other conservative writers into a thoroughgoing reassessment of their movement, their party, and themselves—and wondering who among them will do a complete ideological volte-face—has become a parlor game in Washington journalism and intellectual circles. Rubin seems farthest along that road. But Boot turned quite a few heads at year’s end with a column in Foreign Policy headlined “2017 Was the Year I Learned About My White Privilege,” in which he wrote:

It has become impossible for me to deny the reality of discrimination, harassment, even violence that people of color and women continue to experience in modern-day America from a power structure that remains for the most part in the hands of straight, white males. People like me, in other words.

It’s hard to imagine these folks becoming liberals, but it’s also pretty difficult to picture someone staying a conservative after experiencing an epiphany like that.

Frum insists that he is still a conservative and writes in Trumpocracy that he wants “a conservatism that can not only win elections but also govern responsibly, a conservatism that is culturally modern, economically inclusive, and environmentally responsible.” His is a far more polemical book than Wolff’s, and Frum is a skilled polemicist, capable of producing lines that carry rhetorical precision and force but stop short of screaming for attention:

Trump has contaminated thousands of careers and millions of minds. He has ripped the conscience out of half of the political spectrum and left a moral void where American conservatism used to be.

If journalism is the first draft of history, Trumpocracy reveals Frum’s intent that he be one of the first out of the gate offering a second draft. He acknowledges in his introduction that there is a risk of events overtaking his arguments and proving some of them wrong; however, he adds, “if it’s potentially embarrassing to speak too soon, it can also be dangerous to wait too long.”

Frum’s warning is expressed in his subtitle—that Trump’s rule is a very real threat to the republic. At other times in his text he calls Trump a threat to democracy. Those are two different things—“republic” refers to a body of laws, “democracy” to majority rule—and while it’s true that Trump is a threat to both, it would have been helpful to readers unsure about that distinction if Frum had explained both threats in more detail and laid out why they’re different. Nevertheless, his broader warning about what the alert citizen should be on the lookout for is on point:

The thing to fear from the Trump presidency is not the bold overthrow of the Constitution, but the stealthy paralysis of governance; not the open defiance of law, but an accumulating subversion of norms; not the deployment of state power to intimidate dissidents, but the incitement of private violence to radicalize supporters.

The book is organized into chapters with dramatic titles: “Enablers,” “Appeasers,” “Plunder,” “Betrayals.” “Enablers” discusses WikiLeaks and various fake-news purveyors and includes a sobering anecdote about “the single most circulated fake story of the election”—the news (false) that Pope Francis had endorsed Trump, which popped up first on a website made to look like that of a local TV news station and then on a website called Ending the Fed (both fake). The story was seen by more than one million people. “Appeasers” is about how establishment Republicans went from saying “Never!” to their current state of servility.

“Plunder,” my favorite chapter, provides a rich catalog of Trump family pelf that may be useful one day to Democratic impeachment committee staff. As with presidential lies, these episodes have been so numerous and so shocking—yet simultaneously rendered so pedestrian by their repetition and the casual attitude with which every Trump family member advances them—that we can’t begin to remember them all.

If you squint hard, back through time’s mists, you may recall the phone call Trump placed to Argentine president Mauricio Macri six days after his victory. Why this relatively obscure head of state, alone among the leaders of South America? We don’t know. But we do know that at the time, a Trump-licensed building in Buenos Aires was stalled. Miraculously, the next day, someone cut through the red tape, and the project was moving forward. Trump also put his daughter Ivanka on this call. She has known Macri since she was young, but she is also still involved in her father’s business. We learned of all this only through the Argentine media.

Frum’s criticisms are not limited to Trump. He devotes several pages to an attack on recent Republican efforts to suppress the votes of Democratic-leaning constituencies, advancing the argument, which many conservatives are still loath to make, that Trump, far from being an aberration of modern Republicanism, is in fact its logical endpoint:

It was not out of the ether that Donald Trump confected his postelection claim that he lost the popular vote only because “millions” voted illegally. Such claims have been circulating in the Republican world for some time, based in some cases on purported statistical evidence. Beyond the evidence, however, was fear: fear that the time would soon come, and maybe already had come, when democracy would be turned against those who regarded themselves as its rightful winners and proper custodians.

Conservatives, he writes later, will never abandon conservatism. If the day comes when they conclude that their side can’t win elections democratically, “they will reject democracy.” Trumpocracy warns that the day of reckoning is upon us—that the liberal democracy that is our heritage “imposes limits and requires compromises,” and that Trumpism is its mortal enemy. As the lies mount, questions that once seemed overwrought can no longer be put to the side. We probably have three years of this—at least—to go.

—January 25, 2018

This Issue

February 22, 2018

God’s Own Music

The Heart of Conrad

Doing the New York Hustle

-

1

Glenn Kessler and Meg Kelly, “President Trump Has Made More Than 2,000 False or Misleading Claims over 355 Days,” The Washington Post, January 10, 2018. ↩

-

2

Michael Wolff, “‘You Can’t Make This S— Up’: My Year Inside Trump’s Insane White House,” The Hollywood Reporter, January 4, 2018. ↩

-

3

Seth Abramovitch, “Michael Wolff Reflects on a Wild Week and Trump’s Anger: ‘I Have No Side Here’ (Q&A),” The Hollywood Reporter, January 6, 2018. ↩

-

4

See also Amy Knight’s “The Magnitsky Affair” in this issue. ↩