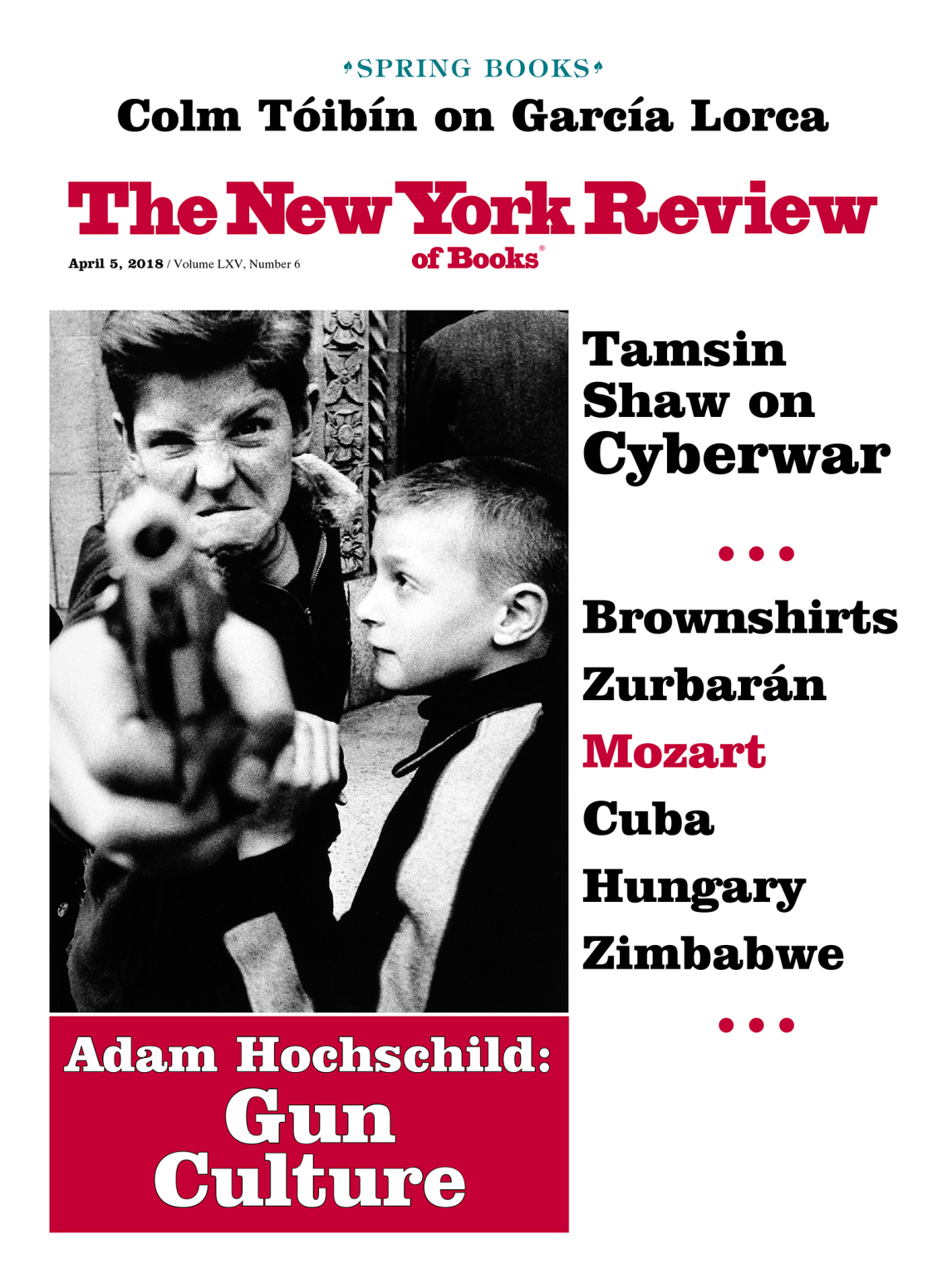

This is what the great photographer Brassaï, who spent a lifetime recording the merry-go-round of twentieth-century Paris, had to say about his work: “I hunt for what is permanent.” Peter Hujar, who photographed New York and died in the city in 1987, could have said the same thing. Hujar’s achievement, the subject of a compact, engrossing retrospective now at the Morgan Library and Museum, has a nerve-wracking power. Here is an artist who yearns for the certainty of forever while refusing to deny the indeterminacy of the present. Hujar explores a considerable range of subjects. The exhibition, entitled “Peter Hujar: Speed of Life,” includes portraits of friends, erotic nudes, nocturnal cityscapes, and studies of animals in the countryside. Hujar responds to different subjects in different ways. He’s there for the subject. The work never suggests a signature style. Avidity itself is his style. Henry Miller called Brassaï the eye of Paris. Peter Hujar is the eye of New York.

“Peter Hujar: Speed of Life” arrives in the city he called home at a time when interest in photography is at high tide. This medium, for much of the twentieth century a fascinating outlier in the visual arts, can now claim a prestige equal to if not greater than that of painting. Major museum exhibitions of work by Diane Arbus, Irving Penn, Stephen Shore, and the still-underappreciated Indian photographer Raghubir Singh are accepted as inevitabilities, as essential to our cultural life as a show of Michelangelo’s drawings. There’s cause for celebration in photography’s hard-won success. But there is also cause for concern, because we risk losing track of what is prickly, unruly, and essentially dissident about even the most artful of photographs. Photography, perhaps more than any other medium, sets in high relief the vexed relationship between art and life. Looking at a photograph, there is no easy way to determine whether we are held by the facts that the camera has revealed or by the particular way that the photographer has interpreted the facts.

When we find ourselves bewitched by Nadar’s portrait of Baudelaire, is it the photographer’s treatment of the writer or the writer himself that most fully engages us? And if it’s some combination of the two, as is surely the case, then how do we disentangle this confounding dynamic? Is it possible? Is it even desirable? Looking at Hujar’s portrait of a reclining Susan Sontag, who was a friend and wrote a brief introduction to the only book he published during his life, we may feel similarly perplexed. Is it Sontag who interests us? Or Hujar’s view of Sontag? Writing about Hujar, Sontag argued that photography is fundamentally romantic, because it makes “the familiar appear strange, the marvelous appear commonplace.” But we didn’t need photography to tell us that the familiar can appear strange or the marvelous appear commonplace. What photographs do and don’t do and can and can’t do is much murkier than many choose to imagine. At one time or another everybody who cares about photographs has wondered at the extraordinary appeal of certain amateur snapshots, which hold us precisely because they’re artless—not in spite of but on account of the apparent absence of an auteur.

More than any other major exhibition seen in New York in recent years, the Hujar retrospective reclaims for us the qualities of promise, possibility, uncertainty, and doubt that are such essential elements in the photographic experience. Although there have been significant shows of Hujar’s work in recent years—at the Fraenkel Gallery in San Francisco and the Matthew Marks and Paul Kasmin galleries in New York—there remains much to learn about the shape and contours of his achievement. Museumgoers who look closely at photographs will be captivated by the warmth and refinement of Hujar’s prints, which he made himself, in what was by all reports a rather primitive darkroom. Their delicacy and variety reflect his concentrated, impassioned artistry. When you explore Hujar’s portraits, nudes, cityscapes, and animal studies, you discover an imagination that moves in different directions. The unity of his art depends not on a particular way of approaching the world but on the character of his curiosity.

Hujar died of AIDS-related pneumonia in 1987 at the age of fifty-three. He was a figure to be reckoned with in the East Village avant-garde and had a number of exhibitions during his lifetime, both in the United States and Europe. His friends believed he could have had more success than he did, if only what was charismatic and seductive about his personality hadn’t been equaled by what was prickly and diffident. His dashing looks, razor-sharp mind, and unfettered promiscuity have been recalled by a variety of friends, most of whom also recall the penurious lifestyle that some saw as a choice and that everybody believed he embraced with an almost aristocratic aplomb.

Advertisement

Most of what has been written about Hujar since his death is more in the way of memoir and biography than critical evaluation. He was very close to David Wojnarowicz—as a lover, friend, and collaborator—and he figures prominently in Cynthia Carr’s first-rate biography, Fire in the Belly: The Life and Times of David Wojnarowicz. The beautiful catalog published by the Fraenkel Gallery to accompany its 2014 exhibition, “Peter Hujar: Love and Lust,” includes a memoir by the critic Vince Aletti and an interview with Fran Lebowitz, both close friends. The catalog of the Morgan retrospective offers recollections by Steve Turtell, who was a friend, and Philip Gefter, who met him, as well as an introductory essay by Joel Smith, who organized the show.

Hujar’s childhood wasn’t easy. It may have left him believing that life was of necessity an improvisation and that he would always need to figure out everything for himself. His father was gone by the time he was born. His mother, a waitress working in Manhattan, sent him to live with his grandparents in rural New Jersey, where he grew up speaking Ukrainian. Returning to live with his mother during his school years, he had the great good luck to be taken up by a high school English teacher, Daisy Aldan, who was a poet and something of a figure in the New York world of poets and painters.

Hujar studied photography with Lisette Model, a master of the candid portrait with a small but hallowed place in the history of the medium, and participated in a workshop run by Richard Avedon and the artist and art director Marvin Israel. He did some commercial work for Harper’s Bazaar and other magazines. By the 1970s he was moving in the same circles as Sontag and the artists Ray Johnson and Paul Thek, who was a lover for a time. His crowd overlapped a bit with Andy Warhol’s; he and Thek were photographed by Warhol and included in some screenings of Thirteen Most Beautiful Boys. In 1973 Hujar moved to a loft at 189 Second Avenue that would be his home for the rest of his life. His last show, the year before his death, was at Gracie Mansion, a red-hot center of the East Village art scene.

The glamour that can be so much a part of the photographic enterprise, especially when the subjects are the celebrities and demi-celebrities in a big urban center, didn’t really interest Hujar. He probably regarded glamour as a sort of sensationalism. He had no use for that. What may at first appear the bravado of so much of Hujar’s work—the friends reclining in bed wearing little or nothing at all; the faces photographed front and center; the unabashed representations of male desire—is complicated by what I can only describe as his reticence. I find it significant that although his friends regarded him as a very good-looking guy, Fran Lebowitz was convinced that he didn’t believe that he was. Like any photographer, Hujar was a connoisseur of façades, but at the same time he was wary of them. He wanted to know what was behind, beneath, within. In a jaunty self-portrait he wears jeans and a short-sleeve shirt and photographs himself jumping, his left leg kicked up, his right hand crossing his brow in a salute. He seems to be comically mocking his own dashing forthrightness. He’s reporting for duty but he’s also kidding around. He’s holding something back.

When Hujar photographs men looking straight into the camera, I’m left with the feeling that it’s the subject of the portrait rather than the portraitist who is in command. He doesn’t push in hard, the way Avedon so often does. In his portrait of William Burroughs, Hujar seems to be allowing the novelist to set the terms. Burroughs appears relaxed, resolute, and perhaps somewhat guarded. Hujar permits people their protective layers; he wants them to be who they are. (With Burroughs he may not have had a choice.) When he photographs his dark-eyed friend Vince Aletti, we find Aletti confronting the camera with an authority that suggests the poetic swagger of painted portraits by Ingres and Bronzino. Like some of the portraitists of other periods, Hujar doesn’t mind an averted gaze. When he photographs the poet and dance critic Edwin Denby, it’s with Denby’s eyes cast down and apparently closed. A study of Peggy Lee, with her manicured right hand close to her ear and her carefully made-up eyes looking away from the camera, conveys a sense of privacy rare in celebrity photography; but of course this is a portrait of an artist, not a celebrity portrait.

Advertisement

Hujar’s circumspection suggests some of the qualities of an old soul, albeit an old modern soul. I would argue that many of his photographs are closer in spirit to the dramatically lyric work that Bill Brandt had already done in England than to what Avedon and Arbus were doing in New York. The more romantic and contemplative elements in Hujar’s personality help account for the lingering power of some of his boldest studies of sex, sexual identity, and sexual liberation. The frankness of his erotic images would be unimaginable without the new freedom that he and his friends were embracing in the 1960s and 1970s.

But Hujar doesn’t leave it at that. He’s attuned to the complexities and confusions that come with a sexual revolution. He sees the revolution’s comic side. When he photographs a great friend, the drag artist Ethyl Eichelberger, he revels in the silliness and strangeness of what his buddy is up to. He doesn’t smooth out the rough edges. “Drag,” Joel Smith points out in the Morgan catalog, “was a gay folk art.” Hujar responds to the shenanigans of his friends in a carnivalesque spirit. His portrait of John Flowers is indelible crazy fun. Flowers is seated on the toilet, his legs spread wide, his skirt hiked way up, with toy horns attached to his forehead and a big grin on his thickly lipsticked mouth. In a photograph taken one Halloween, Randy Gilberti sports a pair of darkly hairy legs encased in shiny stockings plus a pair of high heels decorated with dark feathery poofs.

Hujar is anything but the dispassionate documentarian. When he photographs a man’s foot planted firmly on the ground the result is an emblem of virility. He lets us know that he likes what he sees. The photograph he made in 1976 of the naked young dancer Bruce de Ste. Croix seated on a simple wooden chair, staring down at his erect penis, created a sensation when it was exhibited in the back room at a show called “The Male Nude” at the Marcuse Pfeifer Gallery in 1978. The photograph, although entirely matter-of-fact, isn’t clinical. There’s something almost philosophical about the sight of the young man contemplating his own manhood. Hujar’s studies of youths with erections, or masturbating, or experiencing an orgasm are acts of romantic sympathy and identification. Like all truly romantic acts, they risk absurdity.

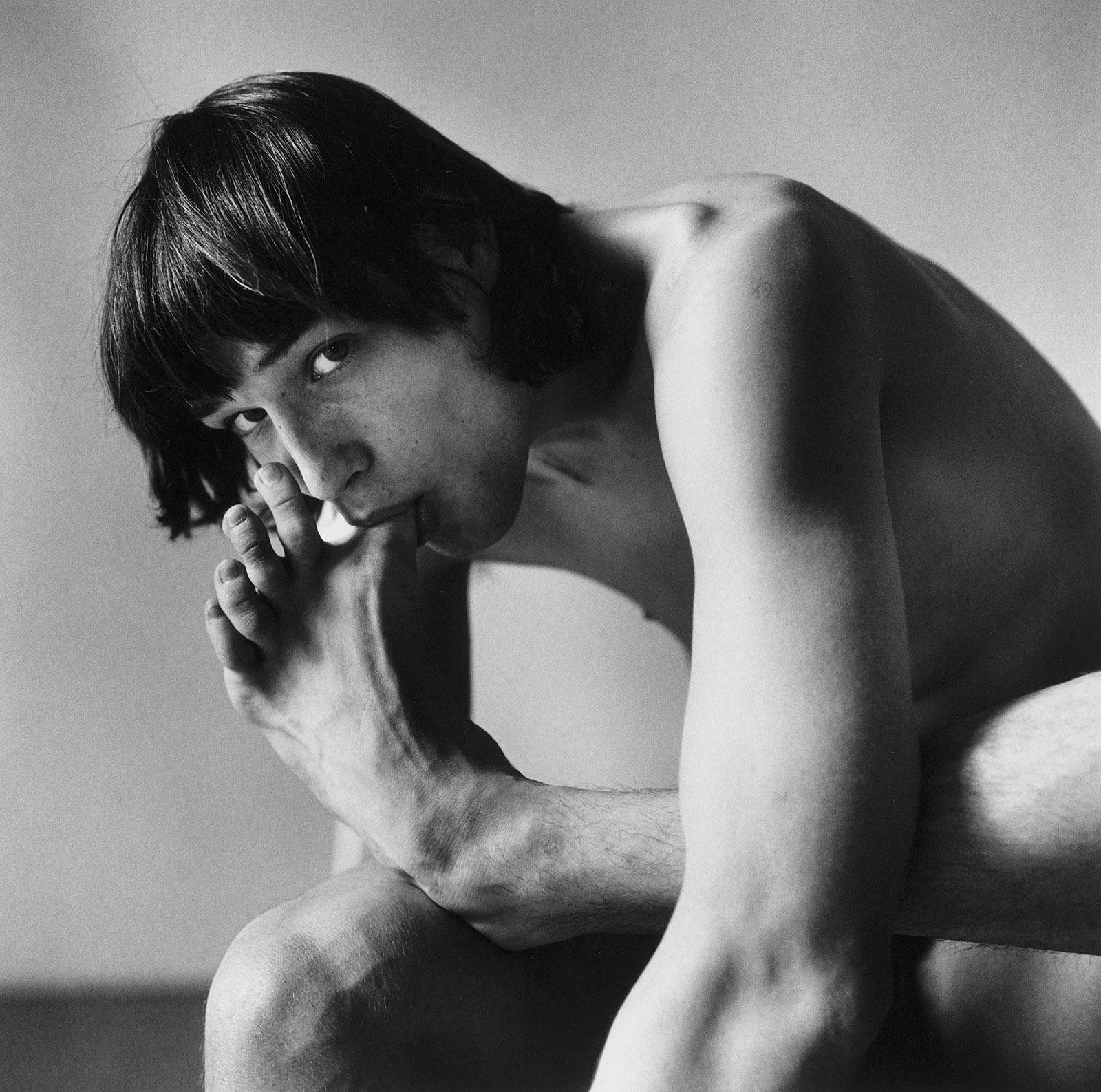

Sometimes, Hujar invites absurdity. In Daniel Schook Sucking Toe, the handsome naked youth with the dark eyes and mop of dark hair stares straight out at us. He’s just daring us to think something—anything!—about the fact that he has the big toe of his left foot firmly planted in his mouth. This may be the sweetest and craziest of all Hujar’s studies of erotic experience. It’s sexy and funny, and you don’t exactly know where the one ends and the other begins.

Hujar’s achievement is full of surprises. His photographs of the night city, with the camera tilted up to catch the dramatically angled skyscrapers and the stepped silhouettes of older apartment buildings, catch the rhapsodic experience of the walker in the city. Hujar discovers a modern chiaroscuro in the bleached white rectangles of lit windows, the inky blacks of mortar and steel behemoths, and the gray murk of the night sky. The abandoned Hudson piers where he and his cohort went to look for sex are part of the story, too, seen not only at night but in the clear light of day. A photograph of a reclining man, focusing on his boots, cutoffs, and hairy legs, has a festive erotic punch.

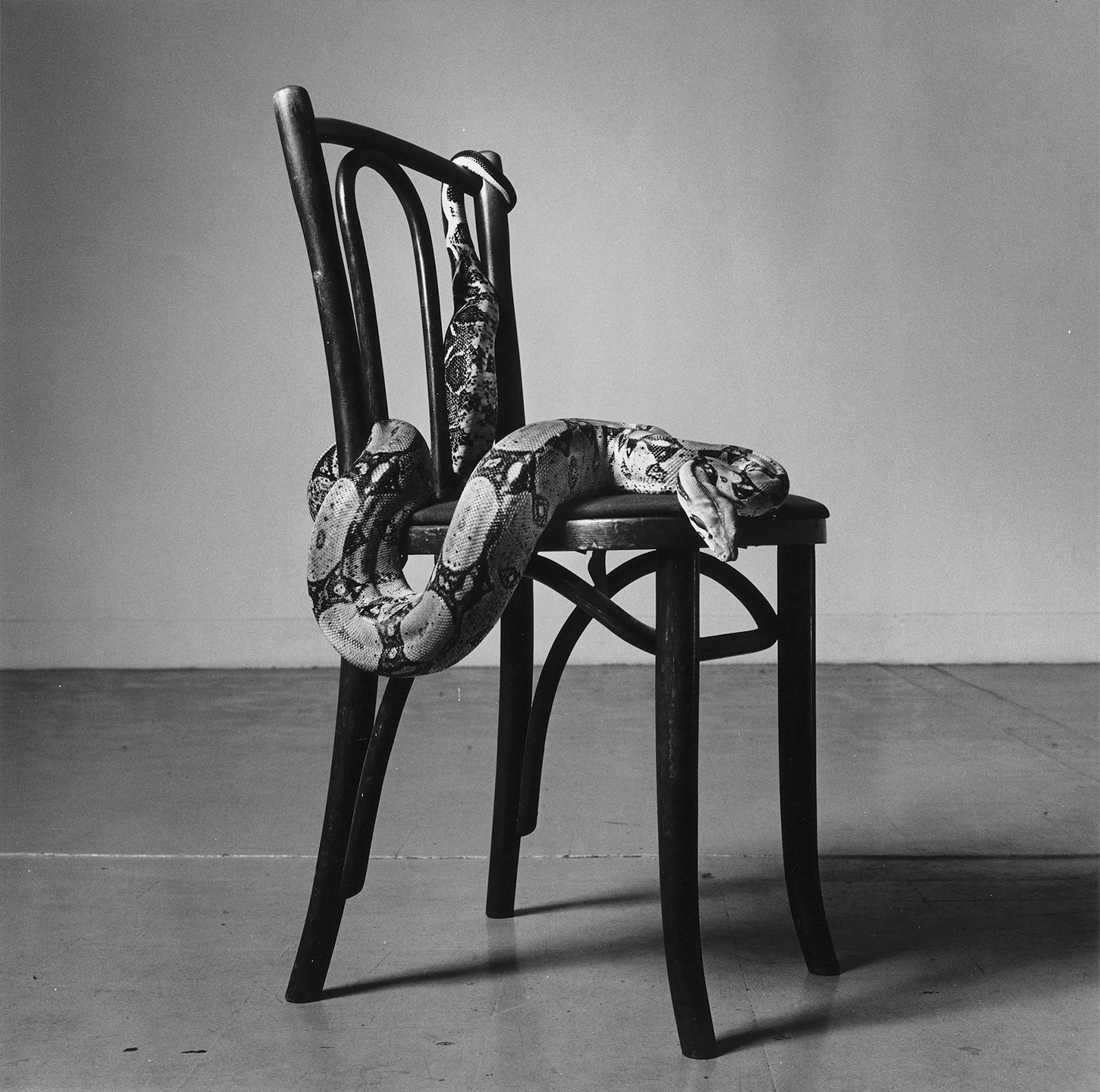

Daylight also suffuses the studies of dogs, snakes, and other animals, often farm animals, done by this artist whom so many for good reason regarded as a consummate urbanist. Of course the pastoral, which Hujar embraced on visits to friends outside the city, is itself an aspect of the metropolitan imagination. The gentle attentiveness that he brings to his four-legged friends isn’t entirely different from the empathy with which he approaches the men and women who came to his loft to pose. There’s a beautiful dignity about Hujar’s studies of animals. His one goose, two cows, and three sheep exude an elegance that has everything to do with their absence of self-consciousness. Or so we imagine. Hujar leaves us with the teasing possibility that his animals know a lot more than we think they do. I am reminded of the paintings that Franz Marc made of horses in the years before World War I.

In the 1970s, awareness of the rich and complex history of photography was expanding at breakneck speed. Hujar was very much part of the excitement. This is when Sontag—who had dedicated her first essay collection, Against Interpretation, to Hujar’s lover Paul Thek—was composing the essays for The New York Review that would become one of her most enduring achievements, On Photography (1977). A pioneering generation of photographic dealers was emerging, which included Hujar’s gallerist Marcuse Pfeifer. The Museum of Modern Art, the first museum to have a department dedicated to photography, redoubled its involvement with the medium under the charismatic directorship of John Szarkowski, while at the Metropolitan Museum of Art a younger curator, Weston Naef, mounted seminal shows including “The Painterly Photograph” and “Era of Exploration.” A posse of deep-pocketed collectors, led by Sam Wagstaff, who was Robert Mapplethorpe’s lover and patron and whom I assume Hujar knew to some degree, were exploring the highways and byways of the medium.

As modern orthodoxies were fading, the pluralism of photography held a particular fascination. Artists, critics, curators, and collectors embraced the heterogeneity of a medium that encompassed everything from the established masterworks of Alfred Stieglitz, Eugène Atget, Paul Strand, and Edward Weston to the anonymous daguerreotypes, tintypes, and snapshots that could be bought in antique shops for next to nothing. Vince Aletti remembers that during the times he spent with Hujar, “whether we were leafing through Bazaar, navigating an opening at the Modern, or pawing over snapshots in a flea market, he had a sharp and knowing eye.”

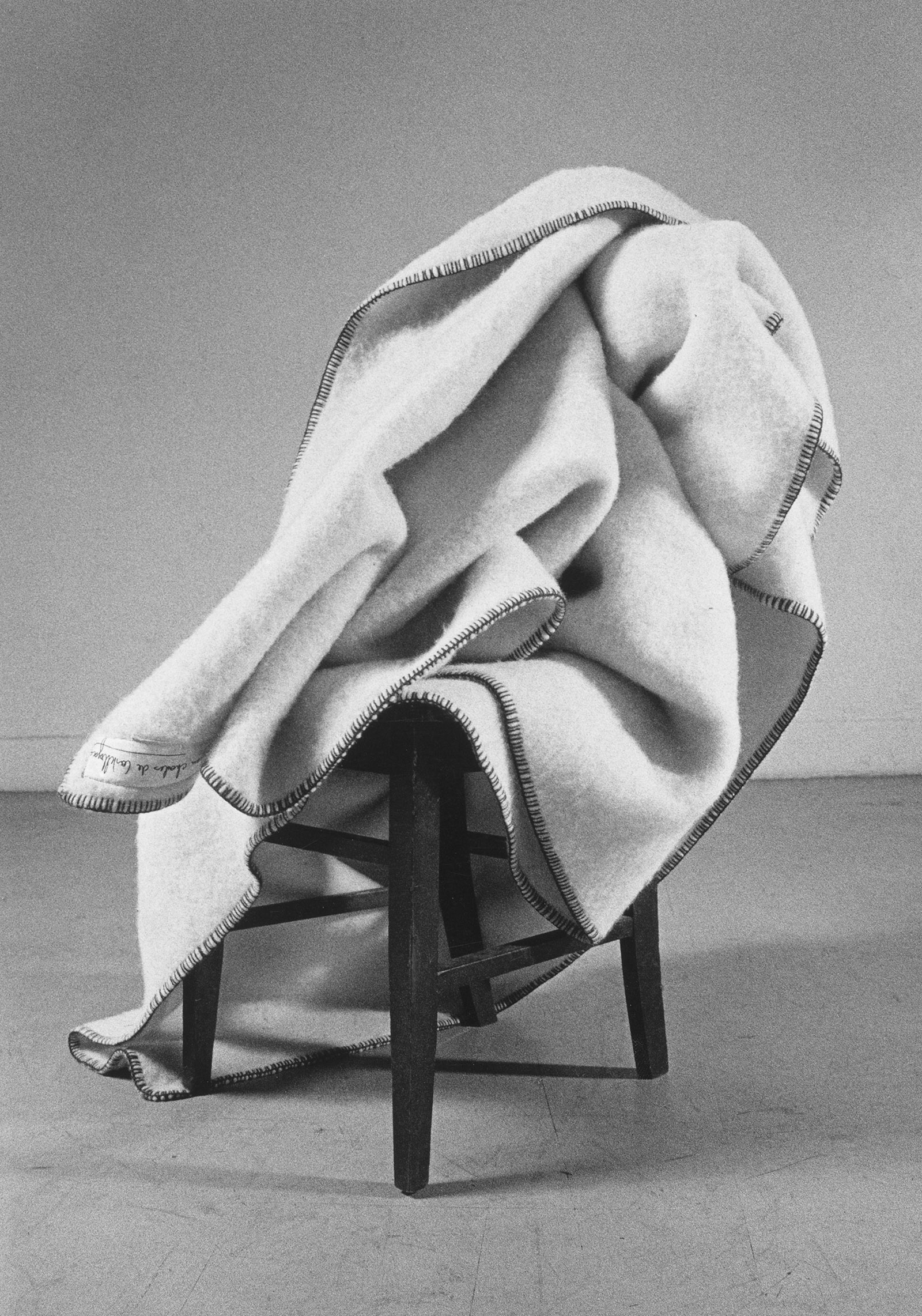

Photographic history became a sort of playground for Hujar. He photographed a young man by the name of José Rafael Arango recapitulating the pose of a woman kicking up her heels in a 1926 photograph by André Kertész, Satiric Dancer, which was already regarded as a classic. That Hujar’s fascination with that history sometimes surfaced in jokes isn’t really surprising. The jokes made the history more approachable. His friend Gary Schneider recalls that when Hujar photographed him in the nude, with his body twisted into a fantastical contortionist shape, what they were aiming for was a parody of one of Weston’s elegant studies of a humble pepper. Weston had a way of bringing out the same sculptural values in a still life and a figure study. Perhaps Hujar was looking for his own way of carrying on the tradition.

Hujar understood as clearly as any photographer of his generation that the more self-consciously artistic a photographer becomes, the more deracinated his work will become. When he kidded around about the old masters of the medium he may have been acting on the same impulse as his drag artist friends; he was sending up the pieties of photographic history in an effort to get to some deeper, truer place. Gefter cites Hujar saying dismissively about Mapplethorpe’s work, “Well, it looks like art.” I’m fascinated by this remark. What Hujar is suggesting is that Mapplethorpe’s cool, crisp compositions, with their suave arabesques and neatly carpentered angles, are little more than glib impersonations of the norms and forms of the high art tradition.

Hujar and Mapplethorpe regarded one another warily. There are certainly some parallels that can be drawn between their sexually charged homoerotic subjects. But Hujar dismissed Mapplethorpe’s work as fundamentally slick and commercial. I do not think he was wrong. For Mapplethorpe, style is a mask. Hujar operates on an altogether different level. Where Mapplethorpe is armored, Hujar disarms. Hujar refuses to be the impresario of his own appetites. He uses art—what some might call artfulness—to dig deeper into reality. That’s what makes his photographs feel so alive.

Hujar captures the give-and-take of the New York he knew, with all its eroticism, humor, conviviality, craziness, melancholy, and romance. Early one morning in 1976 he was wandering around downtown and stopped to photograph the San Gennaro Street Fair at an hour when nobody was there. The sun is already rising. The street lights are still on. Light glances off the cobblestones. A truck recedes in the distance. New York City is shaking off its dreams, preparing for the day ahead. The photograph is darkly optimistic. So was Peter Hujar.

This Issue

April 5, 2018

Bang for the Buck

Beware the Big Five

As If!