Language has many forms of quiet kindness, refusals of stark alternatives. “Never” can mean “not always,” and “impossible” may mean “not now.” Insomnia may mean a shortage of sleep rather than its entire absence, and when Gennady Barabtarlo writes that “Nabokov typically remembered having his dreams at dawn, right before awakening after a sleepless night,” or indeed calls his own book Insomniac Dreams, we are looking not so much at a paradox as a touch of logical leeway. There is no need to go “beyond logic,” as Nabokov says one of the characters does in his story “The Vane Sisters,” but we do often need to bend it a little, ask it to relax.

In October 1964, Nabokov began the experiment that Barabtarlo expertly unfolds for us:

Every morning, immediately upon awakening, he would write down what he could rescue of his dreams. During the following day or two he was on the lookout for anything that seemed to do with the recorded dream.

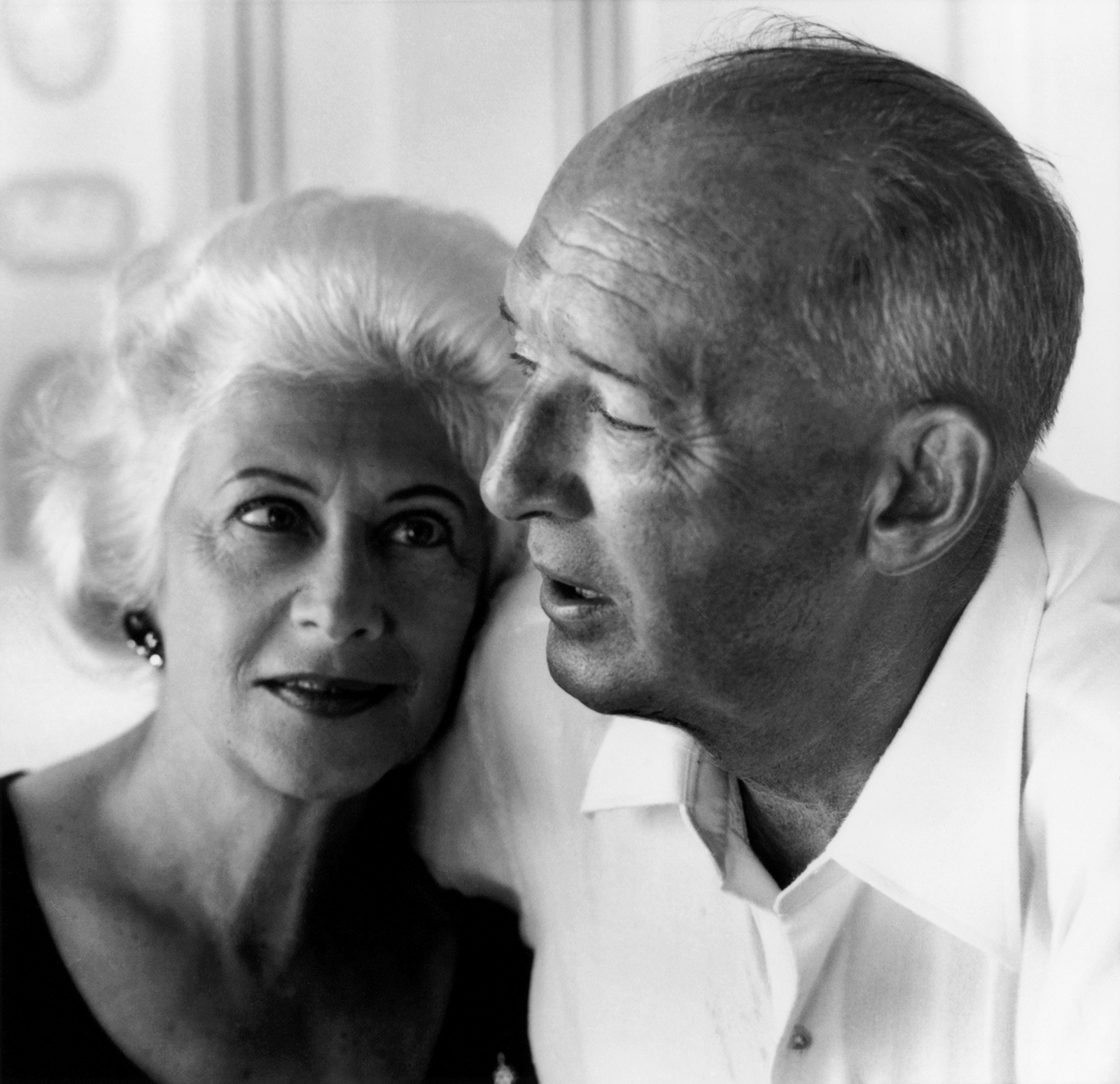

He continued the record, written in English on index cards now kept in the Berg Collection of the New York Public Library, until the beginning of January 1965. He and his wife, Véra, were living at the Palace Hotel in Montreux, Switzerland. Lolita and his teaching career at Wellesley and Cornell lay in the past. He had published Pale Fire in 1962 and completed his translation of and commentary on Eugene Onegin, which appeared in June 1964. The English version of his early novel The Defense came out in September of that year, and he was working on the Russian translation of Lolita. The novels still to come were Ada, or Ardor (1969), Transparent Things (1972), Look at the Harlequins (1974), and the fragmentary, posthumous The Original of Laura (2009).

The “experiments with time” of Barabtarlo’s subtitle have several points of reference. There is the book An Experiment with Time, by J.W. Dunne, first published in 1927, with several later editions, which prompted Nabokov’s attempt at a dream record. A card dated October 14, 1964, is headed “An Experiment” and the words “Re Dunne” are written in a corner. “The following checking of dream events,” Nabokov writes,

was undertaken to illustrate the principle of “reverse memory.” The waking event resembling or coinciding with the dream event does so not because the latter is a prophecy but because this would be the kind of dream that one might expect to have after the event.

“Not because the latter is a prophecy” is the voice of Nabokov’s caution, and pretty much contradicts Dunne’s claim. His idea is that we routinely dream of the future but deny our experience because we think this can’t happen. Precognitive dreams are as normal as memory or anxiety dreams. They are “ordinary, appropriate, expectable,” but they find themselves “occurring on the wrong nights.” Dunne’s aim is to prove there are no such things as wrong nights for dreams. We just need to understand the structure of time a little better.

Barabtarlo also argues persuasively for two other meanings of the experiment. One involves a new/old relation to whatever is “chronic” and has to do with Nabokov’s biography. He “conducted a lifelong nightly experiment with Time, under a condition where the term ‘chronic’ reclaims its original meaning.” The other identifies Nabokov’s longer fiction as “an extended, specialized experiment with Time.” Barabtarlo implies that all good novels are something of the kind, but thinks “novel” is a poor label for a genre that specializes in

a most difficult, deliberate verbal production of the effects of time passing, jumping, bucking, crawling, elapsing, warping, forking, reversing that we experience but can never quite get accustomed to in the course of life. A better term… would be something like chronopoeia, a time-craft in writing, compositional time-management, the taming of time.

This suggestion fits Ada very well, with its discourse on “the texture of time,” which is also the title of a work by Van Veen, the novel’s hero. Nabokov was working on this material as he compiled his dream records, and Van himself, in the novel, gives a sharp, irreverent lecture on the nature of dreams. Time is “tangible” for Van in his Bergsonian moments, and if he insists that “the glittering ‘now’” is “the only reality of Time’s texture,” it is because “now” is so full of “then.” “The Past…is…a generous chaos out of which the genius of total recall…can pick anything he pleases.” “Time is but memory in the making.”

The 1964–1965 dream notes are at the heart of Insomniac Dreams, and are surrounded by helpful and intriguing background material. An introduction informs us about Dunne’s experiments and the “parallel and contrastive” work of Pavel Florensky, a Russian priest and philosopher, and sets up the story of Nabokov’s relation to dreams. The notes themselves are followed by records of dreams found in Nabokov’s diaries and letters written before and after the planned experiment, and by a generous sample of dreams that appear in Nabokov’s fiction. The book closes with an engaging and mischievous essay on “artistic time” in Nabokov.

Advertisement

The mischief occurs mainly in a section called “Clarity of Vision,” an English version of “clairvoyance.” The term “does not imply foreseeing the future,” Barabtarlo says, “rather, it stands for seeing the future as if it were present.” Nabokov did this constantly. He devised the emoji long before its time: “I often think there should exist a special typographical sign for a smile—some sort of concave mark, a supine round bracket.” He didn’t invent Instagram but “instantogram” (from Ada) comes close. More seriously, Nabokov had a mountainside fall in 1975 that he had already described in a 1974 novel:

Imagine me, an old gentleman, a distinguished author, gliding rapidly on my back, in the wake of my outstretched dead feet first through that gap in the granite, then over a pinewood, then along misty water meadows, and then simply between marges of mist, on and on, imagine that sight!

The prosy part of our mind will suggest at once that a person who goes butterfly-hunting in Switzerland is quite likely to think about the fall he hasn’t yet had, but the uncanny effect remains, and that is what Barabtarlo wants to signal. The act of clairvoyance, in his sense, “is one of those things that are at once awkward to display and a shame to discard. It is a staggering chance meeting an improbable alternative to chance.” Or it is life behaving like a Nabokov novel.

“I confess I do not believe in time” is one of the grander pronouncements in Nabokov’s autobiography Speak, Memory. The Russian version, which Barabtarlo quotes immediately after the English, is as he says “smoother, softer-lit and sadder”: “I confess I do not believe in transient time—a light, gliding Persian time!” “Persian” looks toward the carpet in the next sentence (“I like to fold my magic carpet, after use, in such a way as to superimpose one part of the pattern upon another.”) We may also think of the one-way time of the Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam, where “The Moving Finger writes and having writ,/Moves on”—and will never stop or unwrite anything. Persian time is the opposite of “retrieved time” and “an untrammeled extension of time,” which Nabokov also invokes.

Still, it is one thing to regret the passage of time and another not to believe in it. We can say that for Nabokov “believe in” means something like “endorse” or “accept without protest,” and he won’t do that. Yet of course the literal meaning of the concept doesn’t go away. It’s there to raise the stakes and hint at what Nabokov does believe in: memory, and the continuing presence in the remembered world of every person and place that others would call lost.

Dreams offer a form of debased memory:

Whenever in my dreams I see the dead, they always appear silent, bothered, strangely depressed, quite unlike their dear, bright selves…. They sit apart, frowning at the floor, as if death were a dark taint, a shameful family secret. It is certainly not then—not in dreams—but when one is wide awake, at moments of robust joy and achievement, on the highest terrace of consciousness, that mortality has a chance to peer beyond its own limits.

The high terrace is spectacular, but of course the dreams also have their portion of truth. The dear dead are unlike themselves because they are dead, which is precisely the hindrance the dreamer wishes to ignore.

Nabokov’s brilliant attack not only on dreams but on sleep itself invites a similar double reading:

Sleep is the most moronic fraternity in the world, with the heaviest dues and the crudest rituals. It is a mental torture I find debasing…. I simply cannot get used to the nightly betrayal of reason, humanity, genius. No matter how great my weariness, the wrench of parting with consciousness is unspeakably repulsive to me.

Nabokov is against sleep on principle, and the principle is a good old Enlightenment tenet: the sleep of reason breeds monsters. But in practice he does, like everyone else, need to sleep, and as a lifelong insomniac he longs for what he disapproves of.

His chief objection to dreams is that they are messy and poorly composed, reflect “a dismal weakening of the intellectual faculties of the dreamer,” as Van Veen says in Ada:

At his best the dreamer wears semi-opaque blinkers; at his worst he’s an imbecile…. Owing to their very nature, to that mental mediocrity and bumble, dreams cannot yield any semblance of morality or symbol or allegory or Greek myth, unless, naturally, the dreamer is a Greek or a mythicist.

This is why Freud, who appears in the novel as Dr. Froid of Signy-Mondieu-Mondieu, can only be a quack. It is perhaps worth noting that there are moments in Freud’s work where he seems to be on Nabokov’s side rather than his own. If the point of the dream is both to flag and hide a preoccupation, what could be better than an incompetent allegory? And Freud’s conception of dreamwork, if taken seriously, surely makes all easy or mechanical interpretation impossible:

Advertisement

Just as connections lead from each element of the dream to several dream thoughts, so as a rule a single dream thought is represented by more than one element.

On the night of November 4–5, 1964, Nabokov dreams of a hill that moves off like a ship. Freud would say that the hill comes from at least two sources, and that each of those sources is represented more than once in the dream. Perhaps it is a mutation of the taxi that disappears before Nabokov can pay the driver, and it can’t be an accident that the dreamer is seeing his mother off on a train that turns into the hill-ship, and that the dream ends with his being unable to make out her figure among the crowd of passengers. (She died in 1939.)

It would be absurd to claim to know the meaning of this dream, or even, I would say, to believe it has a single meaning. But we certainly have a good sense of the dream’s mood and worries, and it forms a moving complement to Nabokov’s bid to arrest time at a moment of memory: “Everything is as it should be, nothing will ever change, nobody will ever die.”

Nabokov’s dreams of his father present a similar atmosphere. He doesn’t disappear but he is not himself. He is “gloomy and uncomfortable,” “lonely, melancholy, awkward”—“as though,” Barabtarlo says, “his present mysterious after-death condition made the change of attitude inevitable.” The dream, again, knows a sadness that the waking mind resolutely denies, but the sadness appears figuratively, as a change in the loved person, not as an affect of the dreamer.

In one of these dreams, recorded much earlier than the 1964 experiments, the father is playing a piano—“but he did not play in life,” Nabokov tells the future reader of the card—while the son recognizes the name Rodolphe on the score. This reminds him of the difficulty he has “recently had of ascertaining the age of characters in ‘Mme Bovary,’” and he reminds his father of a “jarring” line in Turgenev where a person of forty-five is called “a little old man.” The father is puzzled, and the son says he himself is “now almost fifty-two.” The father remains puzzled and the son wakes up. In 1922, when he was killed in Berlin, the father was almost fifty-two.

Barabtarlo says that “the coincidence is indeed astounding,” and we can agree that dreams are not always so obliging. But surely the question of age is overdetermined here. As with the mountainside fall Nabokov is likely to have thought quite a lot in his waking life about the occasion, in this instance his approach to the age at which his father died. And the awkward father at the piano has to be, among other things, a portrait of an age-conscious son looking for whatever might be represented by “slow laborious soft unsteady music.”

In the early days of his experiments Nabokov quite diligently tries to find the kind of delayed provocation that Dunne is interested in. He sees an “educational film” on television and notes “the absolutely clear feeling I had of this film being the source of my dream…. This is my first incontestable success in the Dunne experiment.” It was a success because the film seen on Tuesday seems to have provided the soil samples that appeared in a dream noted the previous Saturday. Barabtarlo complicates the story nicely by reminding us that the dream, set in a small museum, “distinctly and closely followed two scenes” from one of Nabokov’s short stories, written in 1939.

But of course it was part of Dunne’s idea that a dream could go both ways. He thought it was possible “that dreams—dreams in general, all dreams, everybody’s dreams—were composed of images of past experience and images of future experience blended together in approximately equal proportions.” Nabokov is more conservative here, commenting that the dream would have found its source in the television program “had the latter followed the former.” Not a fold in time then but an uncanny imitation of one.

Gradually Nabokov leaves Dunne behind, and the recorded dreams concentrate more and more on the past. At the end of one note he says that he “had been rereading…the Russian version of Speak, Memory,” and the dream itself, in its raw, unmanaged regret (and perhaps continuing anger), undoes much of the poise of that remarkable book. Nabokov calls it “a really stunning recollection of early childhood,” saying that he “was again immersed in these dreadful tantrums, those storms of tears with which my mother had to cope when I was 4–5 years old and we were abroad.” In the dream the sobbing boy runs down a white corridor and tries to break into his mother’s room. She does not let him in. When she finally opens the door, his brother has heard the sobbing and joins in. The note ends: “This double performance spoilt the matter and M. instead of consoling me broke into tears herself.”

“I was thinking the other day,” Nabokov writes on one card, “about the odd fact that in my ‘professional’ dreams I so very seldom compose anything. But to-night, at the end of a dream, I was granted a very nice sample.” He is dictating to Véra a passage for an extended version of his novel The Gift, written in the 1930s and published in English in 1963. He speaks a phrase slowly in Russian—he actually writes “in Russia,” which Barabtarlo calls a slip—and thinks he has introduced “a secret strain” into “the theme of nostalgia,” indicating that “before actually anybody had left forever those avenues and fields, a sense of never-returning was already inscribed into them.” The words Nabokov lends to the novel’s narrator Fyodor are, in Barabtarlo’s translation, “No matter what I was thinking of, every thought cast forth my great future like a shadow, extending inward.” As he speaks in the dream Nabokov stresses the idea of “inward” (literally “inside of me”), and wonders whether he should say “great” or “magnificent.” He also thinks, still in the dream, that the phrase “will please and surprise Vé. because I am generally not good at evolving orally anything out of the ordinary unless I have written it down.”

The dream engages in double talk, as dreams so often do. Fyodor is projecting his future successes, which Nabokov, in the dream, reads as understanding loss before it happens. The second effect is very close to the one Dunne was so interested in—think of the premature finality of “left forever” and “never-returning”—but in the end relies on a thesis that is the exact opposite of Dunne’s: not that the future is already in some sense present, but that in memory the past cannot shake off the shadow of the future that has descended on it.

Those abandoned avenues and fields belong precisely to the kind of time Nabokov said he didn’t believe in, and the sense of never-returning was indeed inscribed into them—but inscribed later, when they were abandoned for good, an act of writing masquerading as destiny. Sorrow is more interesting than magic, and the very success of the gesture rests on its unreality. As with the dream of the father, the subject is what the sleep of reason may show when it takes a break from creating monsters.