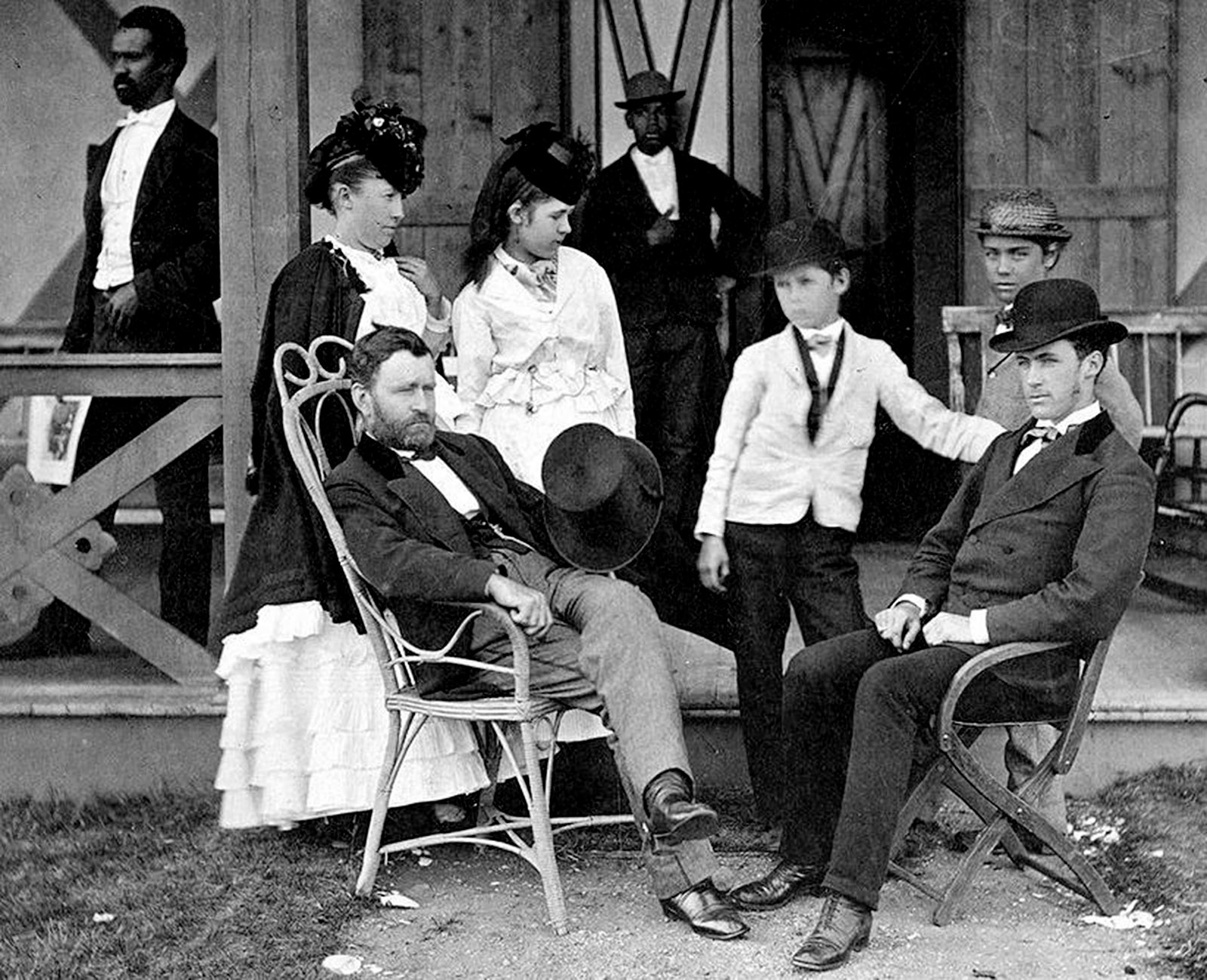

For a century and a half Ulysses S. Grant has been a baffling and inspiring presence in the American literary and historical imaginations. Born in 1822 and raised by a pious Methodist mother, as a young man he was quiet, given to depressions, and lacking much ambition. Only his love of horses seemed to animate him and give him a reason to excel in his education at West Point, which his scheming father desired for him more than he did. In his thirties, he was a complete failure, at times a drunkard, destined to die forgotten. He found his vocation and success on America’s killing fields; his meteoric trajectory in the Civil War makes him a remarkable case of a nobody who became almost everything.

He comes down to us like a figure out of the tangled mythology of Horatio Alger: Grant in his muddy boots, silently contemplating how to kill and capture more Confederates, smoking and chewing eighteen to twenty cigars per day, and writing dozens of clear dispatches to his commanders. Herman Melville envisioned this Grant in his poem “The Armies of the Wilderness”:

A quiet Man, and plain in garb—

Briefly he looks his fill,

Then drops his gray eye on the ground,

Like a loaded mortar he is still:

Meekness and grimness meet in him—

The silent General.

In the end he ruthlessly crushed the experiment of the Confederacy and became a national hero. He has variously been considered a military icon who won a total victory; a presidential model for overcoming his own considerable flaws and a tragic weakness for scoundrels to achieve fame and glory; a literary phenomenon who crafted the most famous deathbed writing in American letters; and a celebrity who was a paragon of humility and modesty. For decades biographers, from the midcentury historian Lloyd Lewis to contemporary scholars like Ronald C. White, have invoked Grant to explore how passivity and dynamism can exist in the same personality. Ron Chernow, the author of prize-winning biographies of George Washington, John D. Rockefeller, and Alexander Hamilton, has written an expansive new life of Grant. It is a work of striking anecdotes, skillful pacing, and poignant judgments. Chernow’s primary subject—and that of numerous previous Grant biographies—is the nature of Grant’s character. We see him survive an odyssey during which many enemies tried to destroy him, including formidable demons within himself.

Grant never mentioned his drinking problem in his Memoirs, but Chernow makes it a leitmotif of his book. After a distinguished if bracing experience in the Mexican War, a conflict he thought “unjust,” Grant served in a series of frontier postings, first in the Midwest, and then in lonely, sometimes meaningless duty on the West Coast. He usually took to drinking when he had idle time, lived without his wife and children, or fell into one of his depressions and went on a bender. Stationed at Fort Humboldt on the coast of California in 1853, he received a promotion to captain, but he could no longer bear the loneliness and resigned from the army. Grant would always either deny or lie about his alcoholism, although, as Chernow shows, he conquered it in the presidency and beyond. We hear of many banquets at which the guest of honor turned his glass over as wine was poured.

In 1854, with borrowed funds, the “guileless” Grant made it to New York, where he was cheated out of his money on the streets and managed to be jailed for drunkenness. By the time the hapless soldier borrowed more money from his West Point friends James Longstreet and Simon Buckner—later to become Confederate foes—and made it to Ohio, he was broke, a failure, and at odds with his domineering father. In the next five years Grant, with his wife, Julia, and his growing family of four children, tried farming and real estate in her native Missouri. He failed miserably at those as well and then sold firewood on the streets of St. Louis in an old faded army coat, prompting Chernow to call him “a bleak defeated little man with a mysterious aura of solitude.”

Here Chernow falls into one of the traps of Grant biography: presenting his years as a down-and-out as a kind of inevitable prelude to his later greatness. Grant’s “momentary disgrace,” he writes, “can be seen in retrospect as his salvation, preserving him for the starring role in the Civil War.” Walking around with a “stoop” in 1859, he hardly looked fit for anything so lofty. Historians should resist the teleology of destiny, no matter how good the story.

On Grant’s ideologically divided families, Chernow shines. Julia Dent, whom the young officer met through a West Point roommate, came from a slaveholding family; her father, “Colonel” Frederick Dent, presided over a plantation, White Haven, southwest of St. Louis. In 1850 the Dents owned thirty slaves. Julia would change her views drastically during the war, partly through loyalty to her husband. She became a Unionist, but her family remained staunch Confederates. Grant’s father and mother were abolitionists. He grew up in Ohio, rigorously opposed to slavery at least “in theory,” as Chernow points out. But in the tumultuous 1850s, because of his marriage, Grant was obliged to live in the midst of slavery and was nearly disowned by his own family for it. His parents refused to attend his wedding.

Advertisement

Chernow sometimes glides over major historical and political developments. But he does demonstrate that the secession crisis “clarified” Grant’s politics and transformed him into an “outright militant” intent on preserving the Union and ending slavery. Not so the Dents; Grant’s domestic world became a scene of “sectional warfare.” Before the war, he not only “dithered” away his talent, says Chernow, he was also trapped between—and almost smothered by—two very different fathers. His own father vicariously lived out ambitions through his son, interfering with him, chastising him, and ultimately basking in the glory he achieved. His father-in-law looked down on the failed army officer who could never be good enough for his precious daughter, then fully supported Confederate independence and slavery during the war that made his son-in-law the most famous man in America. Both fathers, who could not have represented more opposite political positions, ended up living in the White House in their old age, playing the pathetic foils for each other and providing comic relief for the biographer.

In both reality and in Chernow’s book, the two fathers are villains who stand in the way of the hero’s rise. So are two other central figures, General Henry Halleck during the Civil War and Senator Charles Sumner during Grant’s presidency. Halleck, as the administrative general-in-chief, thwarted the young, unconventional westerner in 1861–1862 until Grant’s victories got the attention of Lincoln and the senior officer’s control diminished with some ignominy. During Reconstruction, the imperious Sumner, leader of the Radical Republicans in the Senate, hated Grant, according to Chernow, and blocked him on virtually all questions of foreign or domestic policy, seemingly out of one-dimensional hostility. Chernow shows that the hatred became mutual, although he never quite explains what was at stake, for example, in the prolonged struggle over the possible annexation of Santo Domingo.

Military history is not Chernow’s strength, although he does take account of Grant the strategist, especially the general’s “preternatural tranquility” in the worst of combat. Grant possessed a remarkable talent for military logistics, for anticipating his enemy’s moves or flaws, and especially for taking the offensive. In that calm, while thousands of men killed one another and bullets swarmed about Grant’s body, Chernow believes we find the “riddle of [his] personality.” He could even write to his wife, with nonchalant bravado, that he would never “disgrace” her or “leave a defeated field.” He had been in so many battles already, he wrote Julia from Tennessee in 1862, “that it begins to feel like home to me.” That seems hard to believe, but in his peculiar way Grant probably meant it.

As the scholar Joan Waugh observed, Grant’s “reputation is often determined by whether or not the historian in question believes that the Civil War was a ‘good war.’”1 Since at least the 1950s Grant biographies have followed roughly that pattern. From the 1890s to the 1930s, when the Lost Cause tradition predominated and Robert E. Lee developed into a national cult figure, Grant’s fame waned, and serious historians gave him less attention. The modern Grant revival began with Lloyd Lewis, whose celebratory Captain Sam Grant (1950) took the story to the brink of war in 1861. Lewis died just as his book appeared. Later in the 1950s, Bruce Catton, the country’s most prolific narrative historian of the Civil War, took up the Grant story in three books published over more than a decade.2 Both Lewis and Catton had lived as adults through World War II; no concerns about the justness of war kept them from giving Grant an ennobling biography.

The next stage in the Grant revival came in the 1980s and early 1990s, with the work of William S. McFeely and Brooks D. Simpson. McFeely’s Pulitzer Prize–winning 1981 biography was a post-Vietnam, post-Watergate treatment of Grant. He became in McFeely’s masterful prose the fascinating, dark author of the savagery of the Civil War, not merely its sublime strategist. In 1995, Andrew Delbanco drew on McFeely to claim Grant as founder of the doctrine of massive force, or “annihilation,” used in the world wars of the twentieth century. To Delbanco, Grant was a cultural precursor of the “dead-eyed murderers” in modern American literature, such as the killers in Truman Capote’s In Cold Blood, and the “modern monster” to whom Lee surrendered at Appomattox. In 2006, Harry S. Stout did not forgive or explain away Grant’s responsibility for the carnage of 1864 in Virginia, raising the issue of “just war” doctrine at a time when most historians were avoiding it. Grant, he insisted, sought to shorten the war by the relentless slaughter of his foe.3

Advertisement

Simpson challenged the idea of Grant as a failed, inept president in his fine book Let Us Have Peace: Ulysses S. Grant and the Politics of War and Reconstruction, 1861–1868 (1991) and wrote a superb second treatment of the general’s full military career, Ulysses S. Grant: Triumph Over Adversity, 1822–1865 (2000). He rejected the Vietnam-era, antiwar sensibility in Grant biography and anticipated the recent surge in thick volumes on the former captain’s strange political career. Simpson resurrected the two terms of Grant’s presidency from the dustbin of history, showing that one can never understand Reconstruction if one only considers Grant corrupt or irrelevant.

In 2016, the distinguished Lincoln scholar Ronald C. White came out with a biography, American Ulysses, that brought new attention to his subject’s religion, especially his mother’s Methodism; to Grant’s wife, who played a crucial part in his life; to the general’s fascination with Mexico; and to his reading and writing. White is interested less in questions of whether the Civil War was just than in the details of Grant’s emotional and intellectual bearings, which he argues gave him the verve to support equal rights for African-Americans.4

Chernow’s life of Grant inevitably repeats the work of some of these predecessors, but it has its own insights. The greatest challenge of Grant biography is also its richest opportunity: to explain what Chernow calls the “split personality” of a man of such passive, numbing failure who somehow acquired the “breathtaking audacity” to become the mastermind of the Union’s victory. Chernow writes this story as a kind of homespun national epic. He attends carefully to the ironies of sectionalism, race, and slavery that defined the era and permeated Grant’s life. Chernow is one of Grant’s affectionate biographers: it is hard not to love a soldier on the right side of a just war who drinks too much, smells perpetually of cigars, rarely wears uniforms of his rank, is expressionless and tough, and who, as Lincoln put it about his military leadership, “makes things git!” Chernow gives us a troubled, humble warrior, a man lost and yet found through amazing feats if not grace.

Yet the biographer can still get caught in Grant’s own contradictions. Chernow says that both Grant and Lee were “reluctant warriors who seemed happiest with their families.” On the next page we learn, however, of Lee’s “keen relish for war,” and Chernow notes that Grant chose to destroy Lee’s army in 1864 by costly, aggressive infantry assaults, some of them, like Cold Harbor and the Crater at Petersburg, disastrous. Grant was at times sickened by the carnage he personally caused, but as he ordered General Philip Sheridan to make total war on the Shenandoah Valley he wrote, “Eat out Virginia clear and clean as far as they [Confederates] go, so that crows flying over it for the balance of this season will have to carry their provender with them.” Chernow denies the old charge against Grant as a “butcher,” although clearly the general led a ghastly bloodbath. Most still conclude that his ends justified his means—a debate that may never end.

Chernow handles with care the issue of Grant’s infamous “Jewish order.” Merchants and war profiteers, only some of them Jewish, swarmed around Grant’s army during the Vicksburg campaign, and a few were invited by Grant’s money-grubbing father. On December 17, 1862, in a rage against the merchants as well as against his father, Grant issued the “most egregious decision” of his career. He expelled “Jewish” traders from his military department, an act he later deeply regretted and publicly atoned for on several occasions. He later developed close ties to Jews, speaking in synagogues and appealing successfully for their votes. Chernow leaves no doubt of the sin or of the sincerity of Grant’s mea culpa.

Because of overreliance on Grant’s Memoirs, some errors of fact or problems of judgment mar this gracefully written book. An unschooled reader will get lost in Chernow’s descriptions of long and logistically complex campaigns, notably Vicksburg and Chattanooga in 1863. It seems odd to claim that Grant “doesn’t receive the credit that properly belongs to him” for Sherman’s conquest of Atlanta. Grant did have “genuine compassion” for defeated Confederates, but Chernow’s claim that they “had been restored as…countrymen” at Appomattox is not quite right. The famous meeting with Lee had been a military surrender, not a peace treaty. Chernow miscasts Lincoln’s Second Inaugural as a “forgiving” message, stressing only the final paragraph and ignoring the profound retribution expressed in the first three. Chernow also declares Congress’s override of President Andrew Johnson’s veto of the Civil Rights Act of 1866 “unprecedented.” In fact, President John Tyler had been overridden once and Franklin Pierce five times.

In style Chernow will leave some readers puzzled. He relies excessively on giving detailed portraits of figures in Grant’s life at the expense of explaining their significance. And students of the Radical Republicans, who conceived Reconstruction legislation and constitutional protections for freed slaves, may wonder at the claim that “it was Grant who helped to weave the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments into the basic fabric of American life.”

Chernow eagerly joins the defense of Grant’s troubled presidency. The former general, who after the war was “a helpless casualty of his own fame,” may have been a reluctant, inept politician, but he was hardly without ambition. After the war Grant enjoyed a new, modern kind of fame, played out in the press and before enormous crowds. Everyone wanted a glimpse of the stern captor of Vicksburg and the benevolent conqueror of Lee with the cigar stub in his mouth. Wealthy people gave him houses in Georgetown, in Galena, Illinois, in Philadelphia, in New Jersey, and eventually in New York City. Everyone close to him, including his wife, plied his fame for personal gain.

Grant loved his reputation as the source of the “spirit of Appomattox”—the notion that he welcomed Confederate soldiers, Lee especially, back into the fold as “countrymen.” He earnestly believed that peace could follow all-out war and that charity and compassion could be born of blood and sacrifice. Among the many elements of Grant’s notorious naiveté was this misunderstanding of Southern bitterness and hatred. Chernow calls it the “paradox” of the old soldier’s postwar life: finding the impossible balance between a general’s mercy to ex-Confederates and a politician’s advocacy of black civil and political rights.

Chernow is correct that in his heart, and usually in policy, Grant “never faltered” in his support of the freedmen. He vigorously fought—and for a generation wiped out—the Ku Klux Klan. Grant tried to defend black suffrage, which was so crucial to his own election in 1868 and his reelection in 1872, but was weakened by notorious Supreme Court decisions that Chernow does not effectively explain. In the end he was defeated by the unrelenting violence in Southern politics during Reconstruction, and by the overwhelming challenge of the depression of 1873. The sheer weight of Northern weariness and Congress’s refusal to intervene in the South, such as in outbreaks of violence in Louisiana and South Carolina in 1876, led to Grant’s own acquiescence and inaction.

“Grant mania” brought a showering of gifts and, once he was in office, a litany of scandals to which his name is forever tied. Chernow tells most of these stories of sordid corruption well: the successful effort of Jay Gould and others to corner the market on gold and drive up its price; the Crédit Mobilier railroad fraud network; the extensive Whiskey Ring, in which many government employees and congressmen, as well as a few of Grant’s relatives, pocketed millions in excise taxes; and numerous cases in which shamelessly corrupt Indian agents bilked the tribes on their newly formed reservations. These were just the most famous low points in Grant’s two terms. Chernow believes that his hero was merely a “life-long naïf” whose personal morality ought to go unchallenged. His Grant was an incorruptible man overseeing an age of fee-based spoils and endless bribery.

But is it enough to conclude that Grant just never got over his boundless susceptibility to con artists and Ponzi schemers like Ferdinand Ward, who eventually took the former president, his good name, and every penny he had for a disastrous ride off a cliff? Is Grant merely the victim, not to be blamed for the corruption of his son, a brother, and an assortment of cabinet officials and close aides? A certain charm emerges from this story when it is kept safely in the past. The 1870s, argues the historian Richard White in The Republic for Which It Stands, his new book on Reconstruction, was a time when “random corruption” became a “centralized operation,” when the “profit motive” became inextricably hitched to “public service.”5 Grant by no means created such a world, but he sat haplessly at its reeking center.

At the end of his life, after an extraordinary two-year world tour with Julia, during which the couple was feted like no other Americans before Woodrow Wilson or perhaps the Kennedys, Grant utterly failed—he lost all his money in the downfall of the Wall Street brokerage firm Grant & Ward—and then triumphed one last time. All Grant biographers praise the accomplishment of the dying man’s Memoirs. Completely broke, Grant started writing to try to recoup his fortune and leave an estate to his family. He was first commissioned by Century Magazine to produce essays on important battles in the war, which came out rather lame. But Grant’s prospects as well as his prose found new life when Mark Twain took over the marketing and contract for The Personal Memoirs of Ulysses S. Grant.

The resulting masterpiece of military autobiography is extraordinarily moving. A new edition, the most thoroughly annotated ever produced, provides the general reader and scholar alike with detailed access to the general’s early life and military career. The editor, John F. Marszalek, and his colleagues at the Grant Papers at Mississippi State University have brought together a wealth of helpful information for all future readers and researchers on Grant, his two wars, and his era. The notes are a scholarly achievement, and they could have helped Chernow craft part of his military narrative. Grant probed deeply into his memory and his documents while enduring unbearable pain from throat cancer, which rendered him near the end unable to speak or eat. He settled a few scores, put a few myths to rest, described campaigns and battles with his distinctive clarity, defended himself, hid many elements of his life, and told his favorite stories with an abiding humility. The Memoirs contain some pathos, but the author does not open his heart about the carnage he inflicted in order to save the Union. The quiet, inscrutable one, who so often kept his own counsel in war and peace, had a great deal to say in the end. Almost desperately, even charmingly, he wished to “avoid doing injustice to anyone.” Grant’s was a victor’s story, but as Chernow rightly says, his tales are remarkably fair-minded, while characterized by “breathtaking evasions.”

The problem for a Grant biographer is this: how to keep a critical eye on the old soldier who so earnestly desired to be remembered as a healer and reconciler of post–Civil War memory at the very time the toxic and violently racist world of the late nineteenth century began to defeat him. Former Confederates served as honorary pallbearers at Grant’s extraordinary New York funeral in 1885. Such supporters of reconciliation between the North and South soon lost out to the virulent Lost Cause ideology that would forge the Jim Crow system and celebrate the South’s—and the nation’s—overthrow of Reconstruction. What we get from Chernow’s book, in the end, is the Grant that the general himself tried to impose on us.

Few admired Grant’s Memoirs more than Edmund Wilson. Grant’s writing enthralled him; he found the prose “perfect in concision and clearness.” But Wilson also saw a larger meaning in the book. “If the purified fervor and force that still come through the Personal Memoirs,” he wrote, “may still exhilarate the reader and fill the Northerner with moral pride, it is only because the book makes it possible for him to forget a good deal of the Civil War.” How much do we still forget as we remember?

This Issue

May 24, 2018

Crooked Trump?

Freudian Noir

Big Brother Goes Digital

-

1

Joan Waugh, U.S. Grant: American Hero, American Myth (University of North Carolina Press, 2009), p. 7. ↩

-

2

Bruce Catton, U.S. Grant and the American Military Tradition (Little Brown, 1954); Bruce Catton, Grant Moves South (Little Brown, 1960), and Bruce Catton, Grant Takes Command (Little Brown, 1969). ↩

-

3

William S. McFeely, Grant: A Biography (Norton, 1981), p. 68; Andrew Delbanco, The Death of Satan: How Americans Have Lost the Sense of Evil (Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1995), pp. 139–140; Harry S. Stout, Upon the Altar of the Nation: A Moral History of the Civil War (Viking, 2006), pp. 332, 343. ↩

-

4

Also see major recent biographies by Jean Edward Smith, Grant (Simon and Schuster, 2001); H.W. Brands, The Man Who Saved the Union: Ulysses Grant in War and Peace (Doubleday, 2012); and Charles W. Calhoun, The Presidency of Ulysses S. Grant (University Press of Kansas, 2017). ↩

-

5

Oxford University Press, 2017. ↩