I came to the Met to see Thérèse—Thérèse Blanchard, Balthus’s model and muse. The museum owns two of the eleven paintings Balthus made of the girl between 1936 and 1939, when she turned fourteen, including Thérèse Dreaming, the object of recent #MeToo-related controversy and an online petition, signed by thousands, requesting that the painting either be removed from view or displayed differently. The Met has so far declined to do so.

To my surprise, it is the smaller of the two canvases, titled simply Thérèse, that I find the more immediately arresting. The girl is pushed to the extreme foreground of the composition and cropped rather dramatically at the legs and feet, as though Balthus was zooming in on her with a lens. The effect is jarring and claustrophobic and serves to amplify Thérèse’s striking presence. The picture, though less conspicuously erotic than Thérèse Dreaming, is charged by a tension between its subject’s childishly remote gaze—a mix of dreamy inwardness and pouty disaffection—and her red-jacketed, seductively reclining figure. It is not the pose of a mere child. The tension, if anything, is augmented by Balthus’s awkward depiction of the legs, which defy anatomical logic.

A few galleries away is Thérèse Dreaming. Here she has been placed in a dark cave-like interior and offset by a still life with a crumpled cloth that seems lifted out of a Cézanne painting. As with the other picture, there is a certain jaggedness in Balthus’s articulation of the anatomical form, especially his modeling of the girl’s face. Thérèse’s nose is painted in a way that gives her a strangely harsh quality (harsher than I remember from reproductions), which appears at odds with the refined coolness of the painting. That coolness contains and masks the suggestive core of the picture: the exposure of the dreaming girl’s underwear (apparently unacknowledged by her, visible to us).

I’m reminded of a conversation I had with a friend, a successful painter of highly realistic portraits and figures. He complained of the awkwardness of Balthus’s people: they aren’t real or alive. They look like mannequins. I understood what my friend was saying but tried my best to defend Balthus on the grounds that he was not striving for total naturalism or verisimilitude. His figures weren’t meant to be imitations of real life; they were mysterious emanations from a powerfully subjective vision. Any awkwardness in the paintings, then, was in some part deliberate. Still, I find myself wondering: Had Balthus been a more accurate painter, at least according to my friend’s lights, would he have been a lesser artist?

Mia Merrill, the author of the petition addressing Thérèse Dreaming, writes that “given the current climate around sexual assault and allegations that become more public each day, in showcasing this work for the masses without providing any type of clarification, The Met is, perhaps unintentionally, supporting voyeurism and the objectification of children.” The implication is that the achievement of Thérèse Dreaming has been purchased at the expense of its young female model; that Balthus has, in effect, objectified and exploited her for his own perverse purposes; and that the Met, by continuing to display the painting, is complicit in those perversions. Balthus’s work has thus been assimilated into our contemporary reckoning with patriarchal abuse and privilege: the coercive sexual and ideological power men wield over women in ways both implicit and explicit.

There are various questions that can be asked fairly of the petition and its author. Who exactly are the undifferentiated “masses” to whom it somewhat condescendingly refers, who are so in need of protection from Balthus? Did Balthus’s work only “objectify” his young female models, as passive recipients of the artist’s (and viewer’s) voyeuristic intrigue? Or was he not attempting to present something of the young woman’s own subjective erotic experience, however troubling and taboo—especially in our own time—this may be?

What exactly does Merrill mean when she describes Balthus’s work as “overtly pedophilic”? Is it that Thérèse Dreaming itself constitutes an act of pedophilia or that the painting encourages a pedophilic response in the viewer: “romanticizes the sexualization of a child,” in the words of the petition? Does the potential titillation or, alternatively, disturbance of certain viewers necessarily reflect anything of Balthus’s own intentions? Should it matter, for example, that the sexuality and nudity of Balthus’s girls rarely appear “overt” in any ordinary descriptive meaning of the term—and even less so when compared to representations of adolescent girls by Gauguin, Schiele, and others? (The one obvious exception is Balthus’s seldom exhibited The Guitar Lesson, from 1934, which shows a woman violently grabbing the hair and thigh of her half-naked student.)

Advertisement

Merrill’s petition concludes by recommending that if Thérèse Dreaming is not removed, it should at least be placed in “context,” by accompanying it with the following sort of message: “Some viewers find this piece offensive or disturbing, given Balthus’ artistic infatuation with young girls.” What to make of this claim about Balthus’s “infatuation” with girls, which seems to cast doubt upon the art through an insinuating reference to the artist’s perversion? Can an artistic preoccupation with a subject matter be reduced to a troubling personal one?

Isn’t part of what distinguishes artists the way they transcend their personal preoccupations by making aesthetic order out of the inner disorder that is, to one degree or another, our common human lot? And if so, shouldn’t artists be judged less on the merit of their preoccupations than on how effectively they shape, realize, and make them available to others for contemplation? Finally, can one really “contextualize” art without, in some sense, prescribing the proper attitude to be taken toward it? That is, without foreclosing the possibilities and the unruliness of art itself?

I recently discussed Thérèse Dreaming with an older woman, an architect and former museum conservator. She told me that one thing she disliked about the painting was the brown spot on the girl’s underwear, which guided the viewer’s attention in a way that felt manipulative. I wasn’t sure if she was bothered by the brownness of the spot—with its possible menstrual or scatological connotations—or just the spot’s function as a focal point that drew one in, that narrowed one’s attention (like the punctum of a photograph, in Roland Barthes’s phrase—the point of interest, “that accident which pricks me”). Whatever the case, I was highly skeptical—in fact, in complete denial. I had looked carefully at the painting and had never noticed a brown spot. The whole thing struck me as absurd. The spot, I told myself, must be a projection of her imagination onto the painting.

Feeling unsettled, however, about my own dismissiveness, I returned again to the Met and to Thérèse Dreaming. This time, I saw it, a sort of brown triangular shadow across the bottom of the girl’s panties and the slip of her skirt. I had been wrong after all about the absence of the spot. Still, it remained for me a rather incidental detail. I experienced no “prick”; it did not draw me in; it barely registered at all. Certainly I did not feel that I had been manipulated by Balthus.

The heterogeneity of our reactions to and perceptions of art should, in principle, be a caution against the absolutism of our reactions and perceptions—an incitement, that is, to interpretive humility. There are many ways to look at a painting like Thérèse Dreaming. One can be struck, for example, by the painting’s intrinsic formal properties: its rendering and compositional patterning of line, shape, and color. One can respond instead to the work’s various extra-aesthetic possibilities—the psychological and spiritual meanings it may encode. One can be elated, outraged, or simply unmoved. One can be offended, as Mia Merrill was.

But should any particular reaction be imposed between a prospective viewer and the work itself through a “contextualizing” message? Merrill’s petition sounds so assured about the ultimate meaning and troublesome nature of Balthus’s paintings. However justifiable its larger concerns may be, the petition betrays a strange incuriosity about art, an unwillingness on the part of its author to distance herself from her own convictions. There is something limiting about its politicized and prescriptive attitude toward aesthetic experience. It reflects perhaps a more general cultural exhaustion, as though a certain capacity for wonder—a sense of the inadequacy of one’s own understanding before a given work of art—has given way to contemporary knowingness: a sense that the only or the deepest understanding one needs to have about something is that it is “problematic.”

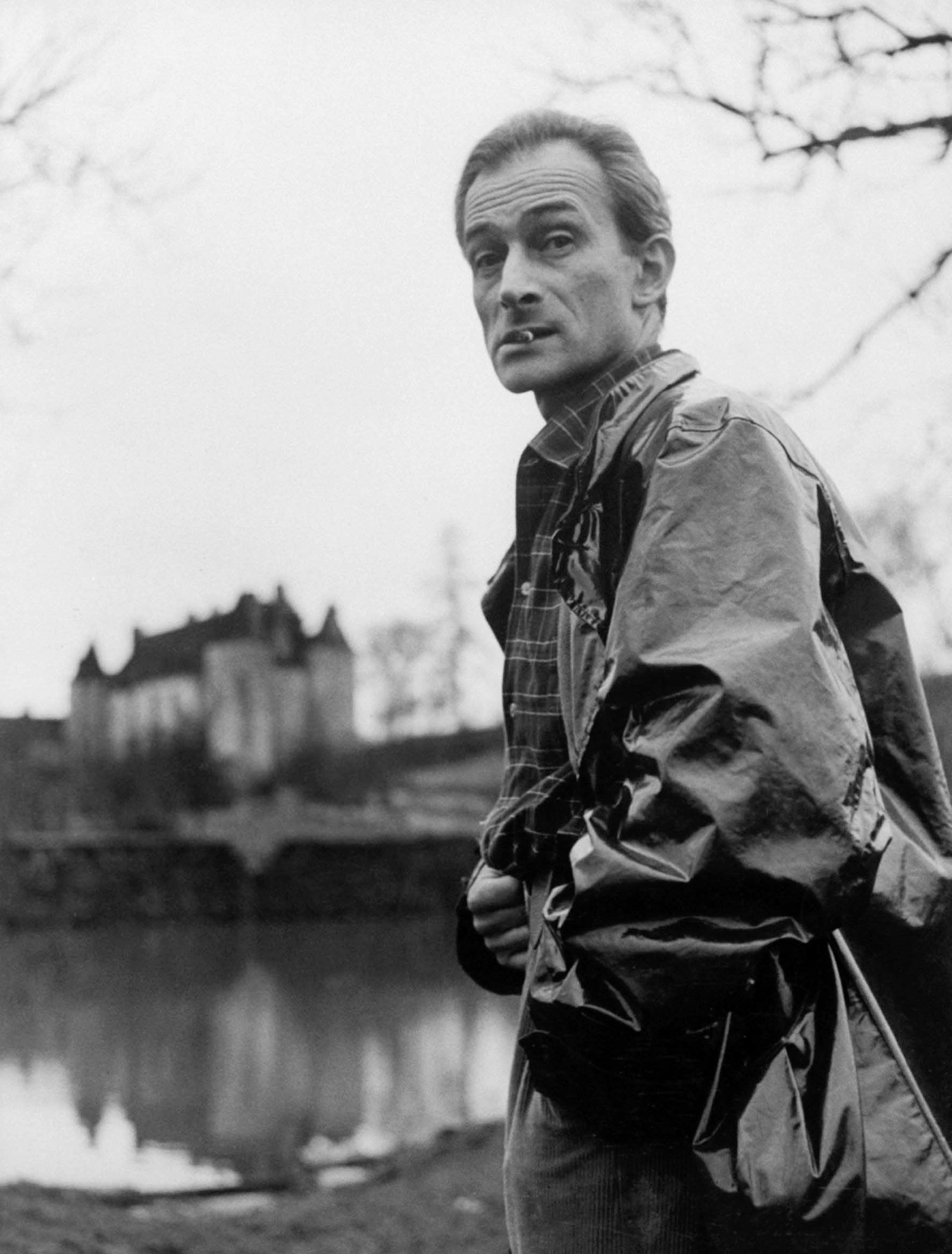

The petition’s charges against Balthus are not exactly novel. In his own day, he was accused of being a pornographer and a pedophile for painting as he did. Still, there is an added irony in the fact that Balthus’s paintings are now being examined from the perspective of our contemporary cultural politics, for throughout his life Balthus insisted on the autonomy of the aesthetic—on its disconnection from the factual and contingent entanglements of history and politics. A late son of the fin de siècle, mentored by Rilke, Balthus became a sort of high priest in the religion of art—a devoted aesthete for whom art served as a supreme fiction that could penetrate deeper realities beneath the surface of things.

Advertisement

As has been well documented, Balthus went so far as to fashion fiction out of his own life, inventing aristocratic origins for himself and denying his Jewish roots. The grandson of an Orthodox cantor on his mother’s side, he proclaimed himself variously the descendant of Lord Byron and of Polish royalty. Such aestheticism is easy enough to mock, but Balthus took it with utmost seriousness. And it seems to provide a starting point from which to view some of his painterly preoccupations.

I’d like, in this connection, to add my own interpretation—or really series of speculative associations—about the meaning of Balthus’s Thérèse paintings. If there is some link between Balthus’s devotion to art and his devotion to adolescence, it may possibly lie in this: adolescence represents a transitional stage between the worlds of childhood and adulthood. The adolescent inhabits both worlds without fully belonging to either one.

The girls in Balthus’s paintings are frozen on the canvas in perpetual states of becoming, with one foot in the timeless unconditioned world of childhood and one foot in the time-ravaged conditioned world of adulthood. They seem to possess a dawning self-awareness, a glancing acknowledgment of their own sexuality that can never quite blossom into full sexual knowledge. Thérèse’s gaze suggests such a duality—lost somewhere between childish naiveté and adult self-consciousness. And I suspect that for an aesthete like Balthus, something about adolescence seemed emblematic of the this-worldly/otherworldly duality of his art, as well as of the condition of his engagement with material reality: abstracted, mysterious, partly averted, still tethered to the dream world of childhood.

Balthus’s painting The Golden Days (1944–1946), for example, shows a girl gazing into a mirror with her legs partly spread. Behind her, with his back to us, squats a man fixing a fire. The painting brings to mind a statement from John Berger’s Ways of Seeing that touches on the passive objectification of women in Western art:

Men dream of women. Women dream of themselves being dreamt of. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at…. Sometimes the glance [women] meet is their own, reflected back from a real mirror.

What is interesting, however, is the way Balthus’s ever-ambiguous painting seems to both anticipate and complicate Berger’s perspective. Is the mirror-absorbed girl in The Golden Days aware of the squatting man? Is she spreading her legs for his or her own pleasure, or in languid unconcern? Is the man merely a figment of her fantasy life? Perhaps the girl’s partial exposure of herself is meant to symbolize the artist’s partial self-exposure. Perhaps the displaced eroticism of the artist’s creative act is symbolized by the displaced eroticism of adolescence—displaced not onto a canvas but back into the adolescent’s not yet realized self. If Balthus’s girls are muse figures, are they also proxy acts of self-portraiture? I don’t know.

An artist told me that his daughter, when she was a child, kindled to Balthus’s paintings because they reminded her of fairy tales. I too have had this impression. But fairy tales in what specific sense? Not, I gather, in the sense of their innocence, for Balthus’s paintings are anything but innocent. Rather, perhaps, in the supernatural or mythological form of the fairy tale, with its landscape of recurring archetypes: the hero, the princess, the good father or mother, the tyrant or witch. As a young artist, Balthus created a series of print illustrations of Wuthering Heights, clearly drawn to the book’s primal, fairy tale–like atmosphere (one such illustration formed the basis of a 1937 painting, The Blanchard Children, that shows Thérèse and her brother, Hubert, dreamily absorbed in their exclusive worlds). And Balthus’s own work seems similarly charged with a mythological force and resonance.

This is also a way of suggesting that Balthus is something he’s not always credited with being: a religious painter—but of a most peculiar kind. There is very little explicitly or doctrinally religious in his work. Instead, Balthus created a mythology for himself, out of his own obsessions. His work unfolds a private universe of signs and symbols—dreaming and reading children, mirrors and windows, chairs and tables, apples and pears—that gain in density and suppleness as they accumulate across paintings and, finally, achieve a kind of cryptic internal dialogue. Take, to cite just one instance, the eerie gnome-like creature of The Room (1952–1954), opening a window curtain to illuminate a recumbent nude, reimagined thirty years later as the artist in The Painter and His Model (1980–1981), standing before a sunlit window, facing away from a table of fruit and a reading girl.

The central object of Balthus’s symbolism, however, is the adolescent girl, along with the cat who so often accompanies her. Indeed, the cat is a mirror of the girl (and perhaps, by extension, of Balthus): both isolated in their dreamy interiority and possessed of the round eyes and cheeks of children; both frozen in an immediate and endless present, outside of time and place, without past or future. Of course, Balthus was far from the first to conceive of the quasi-religious import of girls and cats (cats have been worshiped at least since the Egyptians). But in his work, these symbols are highly particularized and stylized—conjured afresh.

Thérèse Dreaming can accordingly be seen as a type of religious painting. People have criticized the cat lapping up milk in the right foreground of the composition. They find its presence excessive—a redundant and vulgar layering of sexual symbolism. The cat is excessive, but I think for different reasons. To me, it suggests the anarchic intrusion of a fantasy object into a more narrowly descriptive reality—the interpolation, that is, of the artist’s private archetype into the pictorial space. It is as though, as one shifts from the smaller Thérèse portrait to Thérèse Dreaming—from the compositional tautness of the former to the expansiveness of the latter—one finds Balthus plunging deeper into himself, giving himself over more fully to his obsessions and the emanations of his artistic unconscious.

The mythological component of Balthus’s paintings made his work congenial to the Surrealists, who tried to recruit him to their causes. But Balthus disclaimed the association. He had no strategy and no definitive style. Compare, for example, the edgy realism of the Met’s Thérèse paintings with the more burnished formalism of the paintings Balthus made of Laurence Bataille a decade later (such as The Week of Four Thursdays). Or, for that matter, with Nude in Front of a Mantel, painted in 1955 (and now in the Metropolitan’s Lehman Collection): a Morandi-like study in the geometry of the figure that has the flaky texture of a fresco.

And Balthus’s vision was as singular as it was restless, again unlike that of the Surrealists, who tended to make their symbolism transparent and universal by programmatically inverting dream life over conscious life, the irrational over the rational. Balthus, by contrast, trafficked less in transparencies or universals than in private ambiguities. His paintings seem “capable of being in uncertainties, Mysteries, doubts,” in Keats’s famous words. They settle only on the unsettling, enigmatic space between reality and dream.

How, then, is one to defend Balthus’s work, assuming it can be “defended” at all? Not, I think, by denying the erotic quality of the paintings, as Balthus himself was sometimes prone to do, insisting that he was interested exclusively in matters of structural form while implying that any attribution of eroticism to his work was evidence only of the dirty minds of viewers. Is there another way of understanding the sexuality of Thérèse Dreaming (and other Balthus paintings of girls): not as a thing to be wished away or dismissed—either as the infatuation of the perverse artist or as the projection of the prurient viewer—but instead as an undeniable part of the work’s power?

Here I borrow from Lionel Trilling, who in 1958 published an essay on Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita titled “The Last Lover.” The essay sought to defend the book from, on the one hand, its outraged critics, who attacked it as pornography, and, on the other hand, certain of its apologists (among whom Nabokov, another master aesthete, could himself be counted), who downplayed its erotically shocking nature. Trilling’s point was that Lolita was shocking but “not for the reason that books are commonly thought to be shocking.” Rather, for Trilling, Lolita was a modern representation of “passion-love”—an eclipsed mode of writing familiar from Shakespeare to Anna Karenina, in which love figures as tragic, obsessive, and deeply subversive of social convention.

Part of Trilling’s argument was rooted in a claim about the tendency of modern secular societies—in which marriage and other conventions become far less binding and romantic worship is increasingly looked upon as a form of neurosis—to flatten out and invalidate the scandalizing power of Eros. And so, according to Trilling, Nabokov took recourse in the most taboo of subjects in order to reconstitute passion-love in all its violent and tragic tenderness and subversiveness.

Nabokov’s anguished account of erotic rapture in Lolita stands, of course, at quite a remove from Balthus’s veiled renderings of dormant sexuality in paintings like Thérèse Dreaming. (Though how close Nabokov comes to the spirit of Balthus’s girls when he has Humbert Humbert describe the “fey grace, the elusive, shifty, soul-shattering, insidious charm” of his nymphets.) Yet Trilling’s broader notion of reconstituting an old and endangered mode of feeling through the representation of charged subject matter does seem germane to the consideration of Balthus’s paintings and even, perhaps, of his aims.

Guy Davenport, for example, in A Balthus Notebook (1989), his wonderfully epigrammatic ode to the painter, writes that “Balthus is everywhere concerned with returning to subjects of perennial interest that have lost their immediacy and along with it their meaning.”* Most basic among Balthus’s recovered subjects, it seems fair to say, was the human subject itself—and its potential in art to reveal us back to ourselves, educate our sensibility, confront our pieties, even shock us.

It is worth noting how unlikely this achievement was. Balthus’s career (he died in 2001) coincided both with the emergence of the modernist call for pure abstraction—against the representational foundation of traditional oil painting—and the postmodern insistence on the primacy of the political and conceptual. (The artist I know whose daughter enjoyed Balthus’s fairy tale visions is fond of observing how long it’s been since he regularly encountered human beings on the walls of galleries.) Balthus, a fervent admirer of Piero della Francesca and Gustave Courbet—like him, idiosyncratic, renegade explorers of the human figure—did his best to ignore such developments in the arts. And Balthus’s allegiance to the figure was matched by his allegiance to a timeless aestheticized past. There are no televisions or telephones in his work—just as there are no direct references to the historical and political upheavals he lived through. Still, Balthus could not have been entirely immune to the conditions and challenges of his time. The art-historical developments that militated against his success were augmented by the accelerating trends of mass media commercialization and distraction, not to mention the other demystifications of secular society evoked by Trilling.

How then, in short, could a contemporary painter like Balthus reconstitute the immediacy and the meaningfulness of the human subject in art? Or simply make the human figure a still-worthy object of deep aesthetic interest? And how to do so without succumbing to an impersonal, merely virtuosic realism or a disconnected, secondhand neoclassicism—that is, without falling back on and slavishly repeating the same old styles and themes of traditional oil painting? Such questions, consciously posed or not, weigh on any artist wishing to work within a representational tradition yet also wishing to create something individual and authentic. The power of Balthus’s paintings of girls and the transfixing, enraging, scandalizing hold they have had on viewers up until our present moment would appear to indicate his success, against all odds, at answering these questions for himself. They show us childhood anew, as though glimpsed in a darkly glassed mirror. And they reveal the dreamy eroticism of adolescence in all its enigmatic and arresting contradictoriness: spiritual yet sensual, innocent yet desiring, transitional yet timeless.

This Issue

June 28, 2018

It Can Happen Here

Danse Macabre

Brave Spaces

-

*

With respect to the criticism surrounding Balthus’s work, Davenport comments that “a culture’s sense of the erotic is a dialect, often exclusively parochial, as native to it as its sense of humor and its cooking…. The nearer an artist works to the erotic politics of his own culture, the more he gets its concerned attention.” Davenport himself was criticized for his literary imaginings of male adolescent eroticism. ↩