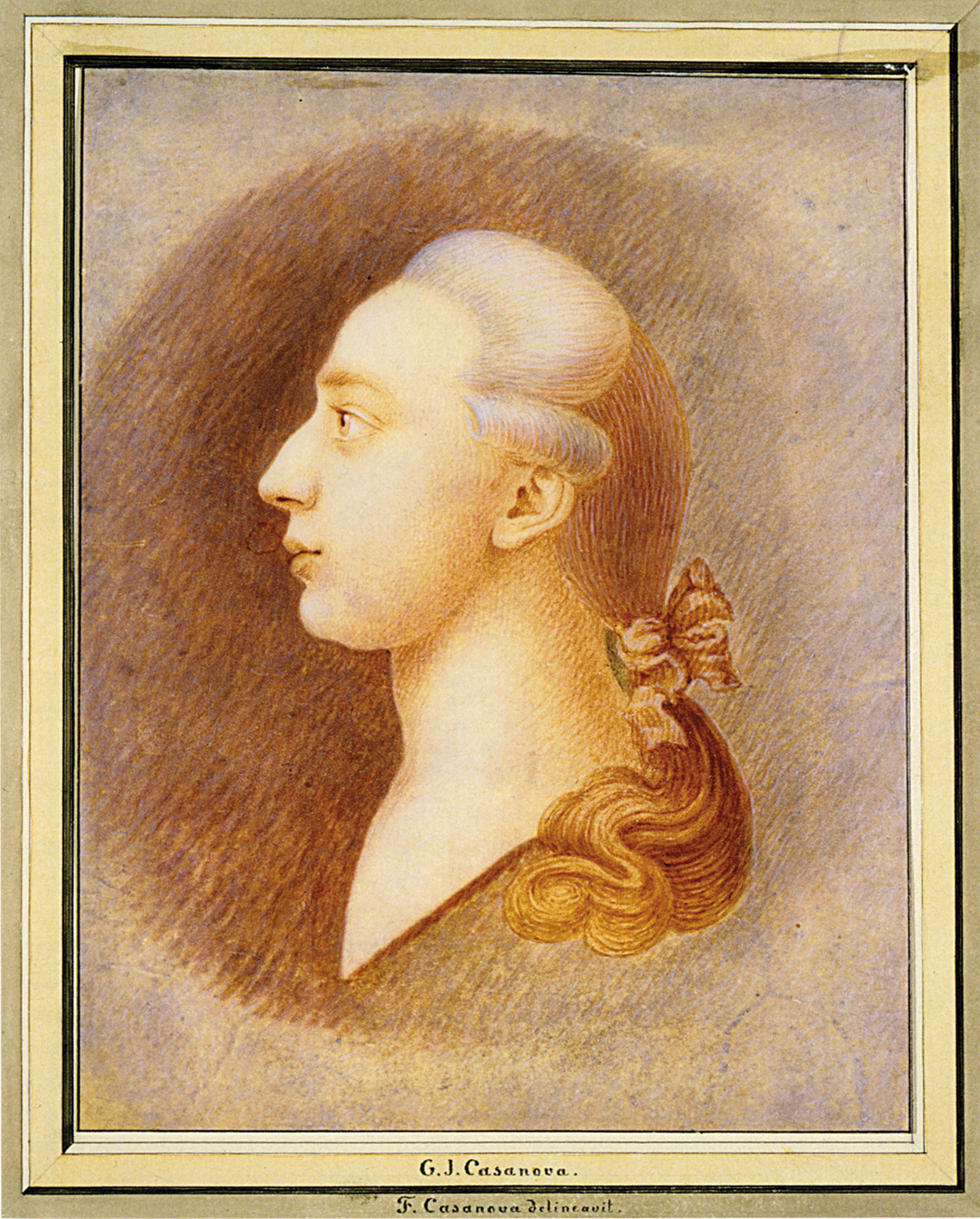

“He would have been a very handsome man had he not been so ugly,” noted Casanova’s friend and fellow bel esprit Prince Charles-Joseph de Ligne, who knew him only at the end of his life. “He is large, as well-built as Hercules, but with the coloring of an African.” This is confirmed in the passport issued to the thirty-two-year-old Jacques Cazanua (sic) by the French government on August 27, 1757, requesting permission for him to travel freely in Flanders for two months. Here he is described as “approximately five pieds 10 and a half pouces in height [6 feet, 2 inches]; with a long, swarthy face and a long, large nose; and a big mouth with brown, bulging eyes.”1 The official description doesn’t quite conform to the portrait drawing of him, made around 1751 by his younger brother Francesco, one of only two authentic likenesses of Casanova to have survived.

The life and times of Giacomo Casanova (1725–1798)—perhaps the most recognizable historical figure of eighteenth-century Europe, Merriam-Webster’s archetype of the “promiscuous and unscrupulous lover”—are the subject of “Casanova’s Europe: Art, Pleasure, and Power in the Eighteenth Century,” a terrific exhibition organized by the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in collaboration with the Kimbell Art Museum and the Fine Arts Museums of San Francisco.2 Following the French National Library’s acquisition of the 3,700-page manuscript of Casanova’s memoirs in 2010 for $9.6 million, there have been two new scholarly editions of this enjoyable, self-aggrandizing, and—for the most part—accurate account of the first fifty years of the author’s life. A Pléiade edition was published by Gallimard between 2013 and 2015; the indispensable three-volume Bouquins edition, first published by Robert Laffont in 1993, has been revised and reissued, the last volume appearing in April of this year. There has yet to be a new English translation, and anglophone readers must still rely on Willard R. Trask’s six-volume History of My Life, which appeared between 1966 and 1970.3

Casanova’s Histoire de ma vie, written between 1790 and 1794, ends abruptly with the author in Trieste in 1774, just before he returns to Venice after an exile of eighteen years. The autobiography records several decades of travel throughout Europe, as well as two visits to Constantinople, in which Casanova covered an estimated 70,000 kilometers in conveyances that ranged from an oxcart to a six-horse luxury Schlafwagen. (Increasingly, his travel was motivated by the need to escape creditors.) Casanova may have visited as many as 134 cities and lived in at least twenty of them. He is estimated to have slept with between 122 and 136 women and a handful of men; to have sired at least eight children (and to have committed incest with one of his daughters); and to have contracted venereal disease eleven times. He fought at least five duels; was imprisoned in Venice, Paris, Madrid, and Barcelona; attempted suicide in London; and avoided assassination twice in Spain. His memoirs contain detailed descriptions of two hundred meals and twenty different wines.

In 1785 the newly unemployed sixty-year-old Casanova had been invited by young Count Joseph Karl Emanuel von Waldstein, whose brother was one of Beethoven’s early patrons, to become the librarian at his castle in Dux (Duchcov), at an annual salary of 1,000 florins. Unhappy in this remote Bohemian outpost, despised by Waldstein’s household staff, and increasingly dismayed by the political situation in France, in the spring of 1789 Casanova was treated by James Columb O’Reilly, an Irish doctor who advised him to stave off depression and illness by writing his memoirs. By January 1791 he was working full throttle on an autobiography entitled Histoire de mon existence. “I write thirteen hours a day which passes like thirteen minutes,” he told a friend. “I am writing my ‘Life’ to make myself laugh and I am succeeding…I enjoy myself because I am not making anything up.”4

Casanova’s life has inspired popular biographies, films, and television series. A few years ago the Max Planck Institute for Ornithology identified a “Casanova gene” in female zebra finches, which show a predisposition for infidelity unrelated to their evolutionary needs. In April 2018 the first “Casanova Museum and Experience”—an augmented reality installation in six rooms—opened in Venice’s Palazzo Pesaro Papafava. Generations of “Casanovaists” have been at work collecting, editing, and publishing the author’s voluminous writings. Their research focuses primarily on verifying the events of his memoirs and identifying (and documenting) the personalities in them.5 As it turns out, Casanova was a generally reliable historian of his own life and times. As he wrote his memoirs, he had recourse to notes and records that he referred to as “his capitularies”—none of which survived among his drafts and papers at Dux or Prague. We learn from a report filed to the Venetian Inquisition on July 21, 1755, that Casanova carried “three small pieces of paper with him at all times, which allows him to write comfortably wherever he desires.”

Advertisement

Casanova also took considerable pains to conceal the identities of several of his mistresses, such as “C.C.” (Caterina Capretta), daughter of a diamond merchant, and the pleasure-loving nun “M.M.” (Marina Maria Morosini), the future abbess of the convent of Santa Maria degli Angeli in Murano. Above all, he protected the aristocratic “Henriette,” the greatest love of his life, with whom he was passionately involved during the autumn and winter of 1749–1750. When she and Casanova parted company in Geneva, she used her diamond ring to etch “Tu oublieras aussi Henriette” (You will also forget Henriette) on a window of their hotel. At least three Provençale noblewomen had been proposed for this enchanting figure. By the most recent consensus, she was Anne Adélaïde de Gueidan (1725–1786), the musical daughter of a cultivated and very wealthy magistrate in the Parlement of Aix-en-Provence and an unhappily married mother of three, who was restored to her family in February 1750.6

Giacomo Girolamo Casanova was born in Venice, in the parish of San Samuele, on April 2, 1725, to Zanetta Farussi (1707–1776), an actress who went by the stage name La Buranella, and Gaetano Casanova (1697–1733), an actor, violinist, and dancer. He was the eldest of six children—four boys and two girls—five of whom survived into adulthood. Both parents left Venice to perform in London the following year, and Casanova was raised by his loving (and illiterate) grandmother, the wife of a shoemaker. One of his earliest memories was of her taking him to Murano when he was eight to visit a witch who stanched his nosebleed. After moving to Padua to study with Antonio Maria Gozzi, a doctor of canon and civil law, Casanova flourished. He mastered Latin by the age of eleven, taught himself Greek and Hebrew, enrolled at the Collegio legista at the University of Padua, and was awarded a doctorate in law in 1742.

In line with his mother’s ecclesiastical ambitions for him, Casanova received the tonsure and the four minor orders in February 1740 and preached his first sermon at San Samuele on Christmas Day that year, aged fifteen. Unsatisfied by his prospects as a “jeune abbé sans conséquence,” he took any opportunity that afforded itself to travel and improve his education, learning French in Rome in 1744 on the advice of Cardinal Acquaviva, and being expelled from that city for bedding the daughter of his teacher.7 (Casanova would perfect his French in Paris six years later as a student of the eighty-four-year-old poet and tragedian Prosper Crébillon, with whom he took lessons three times a week.)

Despite his proficiency in the law, his masquerading as a military officer in Bologna, and modest opportunities for clerical advancement, Casanova found himself back in Venice in 1746 working as a violinist in the orchestra of the San Samuele Theater. Disgusted by this “vile métier,” he enjoyed a piece of exceptional good luck late one evening in March 1746 in sharing a gondola with Senator Matteo Giovanni Bragadin (1689–1767), scion of one of Venice’s most distinguished families (and a confirmed bachelor). Bragadin experienced a stroke en route and was ministered to by a doctor who applied a mercury poultice, which Casanova immediately removed, thereby saving the senator’s life. Acclaimed as a medical genius, an oracle, and a cabbalist of high standing, Casanova was more or less adopted by Bragadin and his circle, who provided him with the trappings of a patrician lifestyle—gondola, lodgings, clothing—and a monthly allowance. Bragadin would continue to support Casanova financially for the next twenty-one years.

An adventurer and gambler in search of advancement, but living primarily for pleasure, Casanova came to the attention of Venice’s Inquisition as early as 1749. His licentious and libertine behavior was carefully monitored. Most offensive was his friendship with prominent young aristocrats, Venice’s social hierarchies being among the most restrictive in Europe. Lucia Pisani, mother of the Memmo brothers, claimed that Casanova had corrupted her three sons—all in their mid-twenties—by preaching atheism to them.8 The Inquisition’s files noted Casanova’s lack of respect for the Catholic religion, his determination “to satisfy his pleasures,” and, most egregious of all, “his attempts to elevate himself in society.”

Ignoring his friends’ pleas that he leave Venice for Florence, on the morning of July 26, 1755, Casanova was arrested at his lodgings by the Venetian Inquisition on charges that included being in possession of contraband salt. Six weeks later he was sentenced to five years’ imprisonment and confined to a small cell in the attic story of the Doge’s Palace directly above the Sala del Maggior Consiglio. Casanova’s account of his fifteen-month imprisonment and his escape via the roof of the palace is told in his memoirs with a brio worthy of Wes Anderson’s The Grand Budapest Hotel. After months of digging through the floor of his cell with a twenty-inch iron pike, in late August 1756 he was transferred to more commodious quarters with a view over half of Venice. He devised a new plan of escape, enlisting Marin Balbi, a fellow prisoner from Genoa, to whom he conveyed the pike in the binding of a large Bible that was used as a tray, on which one of the jailers carried a plate of steaming macaroni to Balbi’s cell. For the next month, Balbi used the pike to bore into the ceiling of his cell, break through the brick wall above, and cut a hole into the ceiling of Casanova’s cell wide enough for the prisoner to hoist himself through.

Advertisement

Making their way onto the roof on the night of October 31, 1756, Casanova and Balbi eventually lowered themselves into the ducal chancellery, only to find the doors leading to the Royal Stairs locked. The opportune arrival of an official with a set of keys, whom they knocked to the ground, allowed the prisoners to exit via the Giants’ Staircase and corral the first gondola they encountered into taking them to Mestre (and thereafter to freedom beyond the confines of the Venetian Republic). Casanova dined out on this story for years to come—his rendition of it might take two hours—wrote it up in Dux, and published it as Histoire de ma fuite in 1787. At more than thirty years’ distance, his memoirs still convey the exultation of stepping into the gondola at daybreak as a free man:

I looked behind me at the beautiful canal, with not a single boat in sight, admiring the loveliest day imaginable, the first rays of the magnificent sun rising from the horizon, our two young gondoliers rowing at top speed…. My soul was overcome with such feeling towards our merciful God, filling me with gratitude and humbling me with such extraordinary force, that my tears poured forth in order to relieve my heart, which was bursting with joy.

In the years following his exile from Venice, Casanova sought to establish himself through financial and diplomatic service to the French crown. Returning to Paris in 1757, he joined forces with the Calzabigi brothers from Livorno in promoting a state lottery to a group of court financiers charged with raising funds to complete the construction of the École militaire, founded in 1750 by Louis XV to train the sons of indigent nobility. With his knowledge of mathematics and passion for gambling, Casanova was the ideal intermediary. He was appointed director of the lottery, oversaw the first draw in April 1758, and prospered from its profits. (Casanova’s biographer Ian Kelly estimates his income in 1758 to have been as much as 120,000 livres.) “He now has a carriage, manservants, and dresses magnificently,” noted an embittered former lover, Giustiniana Wynne—Miss XCV in the memoirs—in January 1759. “How he has managed to insert himself into the best households in Paris, heaven only knows.”

Casanova was less successful in his efforts to set up a cotton and silk dyeing factory in Paris’s Temple district (the present-day Marais) in 1758. A workforce of twenty nubile seamstresses was employed to paint the cotton in imitation of Chinese silks, but the venture failed. Although the French lottery continued to thrive, becoming the Loterie Royale de France in 1776, Casanova was unable to repeat its success elsewhere. In the 1760s his lottery schemes were turned down in London, Berlin, Riga, and Warsaw. Projects to establish scarlet cloth manufacture in Venice, snuff-making in Spain, and a soap factory in Warsaw also came to naught.

In Paris, Casanova enjoyed greater success as a cabbalistic shaman to gullible aristocrats. In 1751 his oracle provided the young duchesse de Chartres with a remedy for her disfiguring facial rash, as well as advice on the state of a friend’s cancer. On his return in 1757, Casanova miraculously cured the comte de La Tour d’Auvergne’s sciatica by painting the five-pointed star of David (“le talisman de Solomon”) on his thigh, wrapping it in three towels, and ordering bed rest for the next twenty-four hours. This led to an introduction to La Tour d’Auvergne’s eccentric aunt, the fifty-two-year-old Jeanne Camus de Pontcarré, marquise d’Urfé (1705–1775)—“a great chemist, an intellectual, extremely wealthy and mistress of her entire fortune.” Casanova was invited to the laboratory in her hôtel on the Quai des Théatins, where the two discussed alchemy, magic, and the Philosopher’s Stone.

Claiming to be in communication with the elementary spirits, Casanova secured d’Urfé’s trust and affection, gained access to her purse and jewels, and agreed to assist in her project of hypostasis—the passage of d’Urfé’s soul into the body of a young man. The ceremony of rebirth was finally performed in Marseilles in April 1763, which entailed making love three times to the marquise in a bath (Casanova was assisted in his efforts by his young Venetian mistress, Marcolina).9 Unsurprisingly, the hoped-for pregnancy in which Urfé would be reborn as a young boy did not materialize, but the marquise remained in thrall to Casanova until her family took action in November 1767 and secured a lettre de cachet to expel him from France.

As he acknowledged—though not without special pleading—this decade-long affair did Casanova little honor. “Absorbed in my libertine ways, loving the life I was leading, I profited from the madness of a woman who, had she not been deceived by me, would most certainly have been deceived by someone else.” Promiscuous he most certainly was, but not, perhaps, entirely unscrupulous. In his account of their first meeting, Casanova notes, “From that day on, I was the arbiter of her soul and I abused my power. Every time I think about it, I am afflicted and ashamed; the obligation to tell the truth in the Memoirs is my way of making amends.”

A romantic fortune-hunter in search of rank and status, Casanova also sought recognition as a man of letters. Voltaire, whom he initially venerated, dismissed him as “un plaisant qui voyage.” Boswell met him in Berlin in September 1764 and described him as “a blockhead…[who] wanted to shine as a great philosopher.” Born in a city where the gondoliers chanted Tasso as they rowed, Casanova knew his Horace by heart and claimed to have read Ariosto three times a year since the age of fifteen. (His memoirs are liberally peppered with Latin quotations from the ancient Roman poets and philosophers.)

In 1769, he sought to return to the good graces of the Venetian authorities as a political historian with his three-volume Confutazione della Storia del Governo Veneto d’Amelot de la Houssaie, which refuted a notorious late-seventeenth-century French polemic as well as more recent criticisms of the Venetian system of government. In 1774 he published a three-volume study of modern Polish history, Istoria delle turbolenze della Polonia, and began working the following year on a translation into Italian of Homer’s Iliad. (It was never finished; only three volumes appeared, between 1775 and 1778.)

Following his autobiographical Histoire de ma fuite, in 1788 Casanova published his first novel, the utopian Icosaméron; ou Histoire d’Édouard et Élisabeth, a rambling, seventeen-hundred page account of a brother and sister’s sojourn in the inner-earth kingdom of the Megamicres. The latter are, in the words of the science-fiction scholar Peter Fitting, “big-littles: tiny, androgynous, multi-colored humans, peaceful and vegetarian, whose primary nourishment is the milk they drink at their life-partner’s breast.” The novel is unreadable today; Casanova believed it would immortalize him.

Instead, it was the Histoire de ma vie, the expansive story of a most unillustrious life, that brought Casanova enduring literary fame. Despite his objections to the contrary, he did indeed follow Pliny’s advice to Tacitus: “If you have not done things that are worthy of being written about, at least write about them in a manner that is worth reading.” As a sensualist and a libertine—as well as a Christian and a monarchist who died despising the new French republic—Casanova’s primary goal was the pursuit of happiness:

To cultivate the pleasure of the senses has been the principal object of my life; I have never considered anything more important… I have also adored the pleasures of the table, and been passionate about any object that could stimulate my curiosity.

Casanova’s minute attention in his memoirs to the culture of appearance—the rituals of rank and protocol—provides the inspiration for the exhibition now at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, of some 250 paintings, sculptures, furniture, decorative arts, costumes, drawings, and prints, primarily from museums and private collections in North America (with the lion’s share coming from the MFA itself). The exhibition follows Casanova from Venice to Paris, Dresden, and London, illustrates the delights of love, sex, gastronomy, and apparel—as well as the despair of imprisonment—and introduces some of the rulers, writers, and lovers discussed in his memoirs.

As Esther Bell notes in her catalog essay on Casanova in Paris, the writer “never expressly mentions his impressions of specific paintings, sculpture, and decorative arts of the period.” Indeed, he scarcely discusses the fine arts in any detail at all. If, during his many visits to “M.M.” at Santa Maria degli Angeli in Murano, Casanova ever noticed the commanding religious paintings by Veronese—exhibited at New York’s Frick Collection earlier this year—he makes no reference to them in his autobiography, nor indeed to any paintings by Veronese in Venice.10 This is the more surprising since two of his younger brothers, Francesco (1727–1803) and Giovanni Battista (1730–1795), were successful painters. Francesco, a battle painter, entered the French Academy in 1761, the year of his meteoric debut at the Paris Salon, which assured him an international clientele and a remunerative career. Two of his energetic, if rather bombastic, landscapes, from a series called Dangers of Travel, painted around 1770, are included in the exhibition. Giovanni Battista, a neoclassical history painter, assumed the codirectorship of the Academy of Fine Arts in Dresden in 1776.

In Casanova’s memoirs there is not a single reference to his Venetian contemporaries such as Giovanni Antonio Canaletto, Bernardo Bellotto, Pietro Longhi, Francesco Guardi, Giovanni Antonio Guardi, Giovanni Battista Tiepolo, or Giovanni Domenico Tiepolo.11 Nor does he mention any of their Parisian counterparts—Nicolas Lancret, François Boucher, or Jean-Honoré Fragonard, for example. Each of these artists is represented by outstanding examples in the exhibition. The only contemporary French artist to merit discussion in the Histoire de ma vie was the seventy-year-old court portraitist Jean-Marc Nattier (1685–1766), whom Casanova admired for the “imperceptible character of beauty” that he brought to “the perfect resemblance of his sitters.” “Where does this magic come from?, I once asked Nattier, after he had painted the ugly Mesdames de France (Louis XV’s daughters) as beautiful as heavenly bodies.”

Casanova met the painter during his second sojourn in Paris (1757–1759), likely introduced by the Venetian actress Zanetta Belletti, “Mademoiselle Silvia,” the mother of his friend Antonio Balletti, and of the seventeen-year-old Manon, whose ravishing portrait Nattier painted in 1757. Casanova was briefly—and unofficially—affianced to Manon, who, after breaking with him in 1760, married a fifty-five-year-old architect (bringing a dowry of 24,000 livres to the union). Invited by the wife of the painter Carle van Loo to a dinner where the newlywed couple would be present, Casanova, still enamored of Manon perhaps, could not bear to see her again.

The meagre documentary evidence for Casanova’s interest in the art of his time should not obscure the affinities—most obviously in subject matter, but also in style—between his autobiography and high Rococo painting. As an example, take Francesco Guardi’s Parlatorio (1746), a view of the expansive visiting room at the convent of San Zaccaria. This is a social space where aristocratic children are being entertained by a commedia dell’arte puppet show, while their patrician elders—some masked, some in long gray wigs—engage in conversation with the novitiates behind the grilles. A splendidly attired matron, in a hooped skirt and fur-lined bodice, offers a circular dog biscuit to a tiny spaniel, adorned with a pink silk bow. At the margins of the canvas, appropriately enough, are members of a less privileged world: a beggar on crutches, with bandages on his head and legs, requesting alms; a woman delivering food (or laundry) in a basket at far right, discreetly beyond the purview of the elegant company.

It was in such a setting—in a convent on the island of Murano—that Casanova embarked upon an unabashedly carnal affair with the patrician novitiate Marina Maria Morosini, in 1753. He was amazed at the ease with which these “holy virgins” could escape their cloisters, and noted that at Carnival the convents were even permitted to host masked balls: “There is dancing in the visiting room and the nuns remain inside, enjoying the festivities behind the ample grille.” Casanova attended such a ball, in the parlatorio in Murano, disguised as Pierrot.

Johann Zoffany’s Self-Portrait in the guise of a Capuchin friar, inscribed “il 13 Marzo, Parma 1779” and painted to celebrate the artist’s forty-sixth birthday, matches Casanova in ribaldry and irreverence. On the table to the left are the tools of Zoffany’s practice (palette, brushes, and flasks of oil); on the ledge above him, a wine glass, bottle, skull, and pack of cards (well-known symbols of Vanity). A rosary hangs from the wall, its beads grazing the edge of an engraving after Titian’s Venus of Urbino. Two condoms are arrayed to the left of the rosary, with pink ribbon at the open end. A third sheath, easy to overlook—and identified by one historian as a piece of paper—is suspended from above the print and can just be seen covering the goddess’s lower body at the right edge of the panel. (Zoffany is hardly subtle).

Fashionable from the 1750s on, especially in England, condoms were made from rendered sheep gut, designed for repeated use, and worn to guard against venereal infection as well as to prevent pregnancy. (Casanova referred to them as “English riding coats.”) He recalled finding a group of condoms at his disposal in “M.M.’s” casino in Murano; to spare the carpet, she insisted that he use them.

Casanova begged his readers’ indulgence as they turned the pages of his memoirs: “Those who believe I am too much of a painter when I recount certain of my love affairs in detail, are wrong to think so unless they find me to be a bad painter.” The editors of the new Pléiade edition of the Histoire de ma vie discern a visual equivalence to Casanova’s manner in Pietro Longhi’s sympathetic conversation pieces. Writer and painter inhabit the same universe and share “a touch which might seem heavy and rough, but which is exceptionally well-suited to give the illusion of life.”

Taking this insight a little further, I suggest that it is in certain erotic paintings by a slightly younger French contemporary—also a great admirer of Ariosto—that Casanova’s preoccupation with the affairs of the heart are matched in paint. Fragonard’s scenes of sexual abandonment and intimacy behind closed doors convey an exaltation and ardor that are comparable to Casanova’s inspired descriptions of lovemaking.12 A painting such as The Desired Moment (see illustration on page 88), of around 1770, conjures Casanova’s most scintillating recollections. In both text and image, the youthful lovers appear “in a state of nature, prey to sensual pleasure and love”; they share agency (and urgency), and consummate their passion as equals.

This Issue

September 27, 2018

Aquarius Rising

Missing the Dark Satanic Mills

Tenn’s Best Friend

-

1

The passport issued to “Jacques Cazanua, Italien” by the duc de Gesvres seems to have escaped the notice of the most ardent Casanovaists. The description in French is: “Taille de cinq pieds dix pouces et demi ou environ. Visage long plein et Bazanné, Le nez long et gros, La bouche grande, Les yeux bruns à fleurs de teste.” Passport-Collector.com, February 21, 2018. ↩

-

2

In Fort Worth and San Francisco, the exhibition was titled “Casanova: The Seduction of Europe,” which is also the title of the catalog. ↩

-

3

See Michael Dirda, “The Pleasures of Casanova,” The New York Review, May 31, 2007. ↩

-

4

Casanova’s manuscript was completed in the spring of 1794, and a chance encounter that summer at the fashionable spa town of Teplice with his employer’s uncle, the Prince de Ligne, gave him his first (and most enthusiastic) reader. Encouraged by de Ligne, Casanova continued to revise his manuscript. His health in rapid decline, in April 1798 Casanova stopped revisions on the final volume and invited a nephew from Dresden, Carlo Angiolini, to visit him. It was to Angiolini that the ten notebooks containing his memoirs were bequeathed upon Casanova’s death the following month. In 1821, Carlo’s children sold the manuscript of Histoire de ma vie to the Leipzig publisher Friedrich Arnhold Brockhaus, who commissioned a German translation from Wilhelm von Schütz that appeared, in twelve volumes, between 1822 and 1828. A pirated French retranslation (from the German) in fourteen volumes was undertaken at considerable speed by Victor Tournachon, father of the photographer Nadar, and between 1825 and 1829 Casanova’s Histoire de ma vie was published in French for the first time, in a form that its author would barely have recognized. In response to Tournachon’s unauthorized publication, Brockhaus enlisted Jean Laforgue, professor of French at the Military Academy of Dresden, to provide an “improved” (and slightly sanitized) version of the original manuscript. A French edition, in twelve volumes, appeared between 1826 and 1838, and was the basis for all future editions until 1960, when Brockhaus, in partnership with the Parisian publisher Plon, brought out a fine scholarly imprint, with extensive notes and bibliographic apparatus. In 2007 members of the Brockhaus family were brought into contact with representatives of the Bibliothèque nationale by the French ambassador in Berlin, which led to the library’s acquisition of the manuscript three years later and the digitizing of the memoirs on its website, Gallica. ↩

-

5

Two scholarly journals were devoted to the cause: Casanova Gleanings (1958–1980) and L’Intermédiaire des casanovistes (1984–2013). ↩

-

6

See Judith Summers, Casanova’s Women: The Great Seducer and the Women He Loved (Bloomsbury, 2006), pp. 163–167. Hyacinthe Rigaud’s portrait of Henriette’s father, Gaspard de Gueidan Playing a Musette, 1735, in the Musée Granet, Aix-en-Provence, is a much-reproduced masterpiece of Rococo painting. ↩

-

7

For Casanova’s entanglements with Barbaruccia, daughter of the lawyer and French teacher N. Dalacqua, see Histoire de ma vie, vol. 1, pp. 237–247. ↩

-

8

Mozart’s librettist, Lorenzo da Ponte—a fellow Venetian whom Casanova may have assisted (minimally) on Don Giovanni—noted in his Memoirs that the Inquisition proceeded against him “because a certain lady complained…that Casanova had been reading Voltaire and Rousseau with her children.” See Lorenzo Da Ponte, Memoirs (New York Review Books, 2000), pp. 214–215. ↩

-

9

Histoire de ma vie, vol. 2, pp. 1092–1102. In the ceremony, Casanova assumes the role of his oracle, Paralis; d’Urfé is Seramis (an allusion to Sémiramis, queen of Babylon); and Marcoline, a Venetian girl who cannot speak French, is introduced as L’Ondine, a deaf-mute who is able to hear (“muette qui n’est pas sourde”). ↩

-

10

See Xavier F. Salomon, Veronese in Murano: Two Venetian Renaissance Masterpieces Restored (Frick Collection, 2017). ↩

-

11

The only member of the Tiepolo family to be mentioned in the Memoirs is Lorenzo Baldissera Tiepolo (1736–1776), “the son of the Venetian painter, Tiepoletto, whose talent was mediocre, but who was an honest boy.” Lorenzo married the daughter of a Genoese bookseller in Madrid who had been generous to Casanova in 1768; see Histoire de ma vie, vol. 3, p. 539. ↩

-

12

Gérard Lahouati, the editor of the Pléiades edition, also evokes Fragonard, who, like Casanova, “succeeds in describing the grace and liveliness of a face, the lightness of a body, the tension of desire, and the rapture of orgasm.” ↩