When Yankee Doodle stuck a feather in his cap and called it macaroni, he was not thinking of pasta. And the author of the ditty, probably a British professional soldier mocking the New England militiamen with whom he fought during the French and Indian War in the late 1750s or early 1760s, was not indulging in mere amiable ribbing of the colonials. Macaroni was an extravagant and self-conscious fashion in male display and an arena in which anxieties about British masculinity were being played out. Over the next decade, back home in England, the image of the macaroni militia officer would become a staple of the booming market in satiric prints. As Matthew McCormack has pointed out in his book Embodying the Militia in Georgian England (2015):

Casting militia officers in the mould of macaronis serves to insinuate that the institution had fallen from its original “patriot” design, as well as suggesting that its officers were sartorially, corporeally, and morally unsuited to the business of war. The “military macaroni” struck home because army officers were vulnerable to accusations of foppery, in an age when they were associated with ornate uniforms, polite sociability, and mannered formality. A critic of the militia in 1785 protested that militiamen are distracted from their purpose by dressing them in “fancy caps and feathers, and other ornaments of parade.”

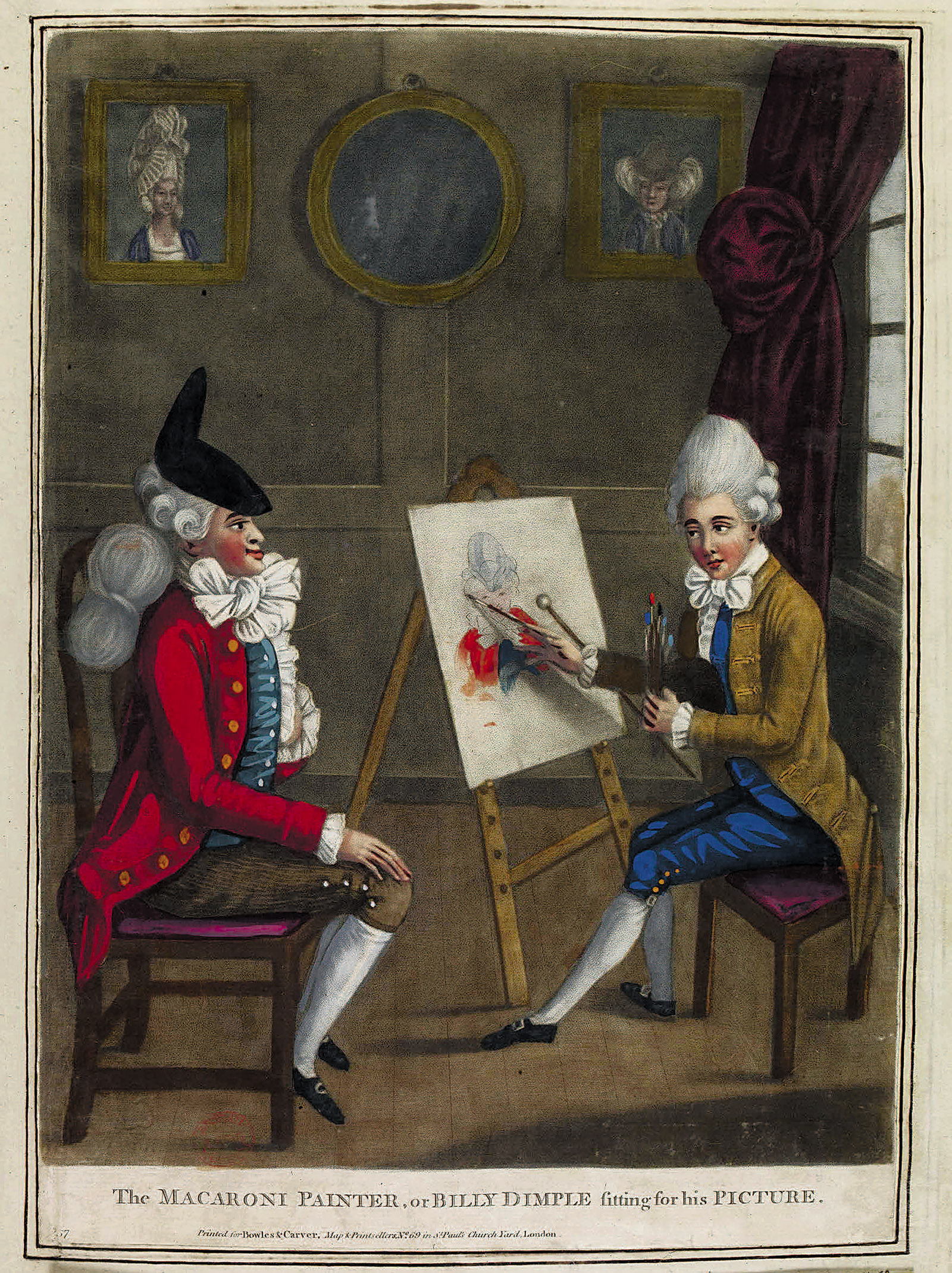

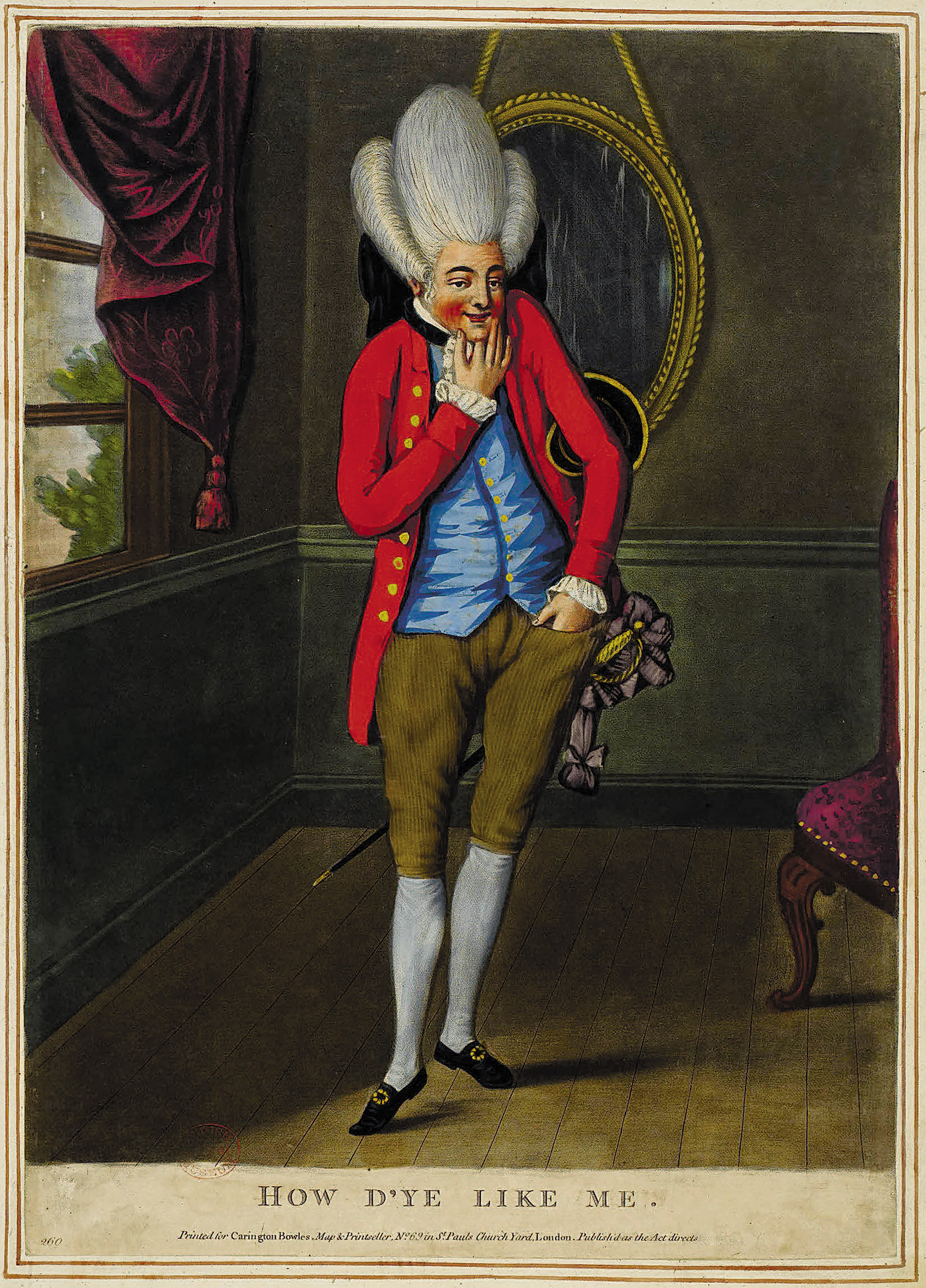

The feather in Yankee Doodle’s cap is also a distress signal, pointing to fears of national degeneracy, cultural subversion, and effeminacy. The images in late-eighteenth-century prints of preening men in tight-fitting militia uniforms with huge frilly cuffs, ridiculously high wigs, and dainty shoes are funny, but they also raise a terrifying question: How can these Frenchified fops be expected to defeat the French?

The use of the term “macaroni,” the subject of Peter McNeil’s fascinating, deeply erudite, and superbly illustrated Pretty Gentlemen, reached its height between 1760 and 1780, though the word remained in everyday use for the rest of the eighteenth century. It did indeed originate with the habit of eating pasta, an outlandish affectation picked up by privileged young men on their Grand Tours to Italy and one that deliberately affronted the cherished self-image of the English as a nation of roast beef eaters. It came, however, to refer to an outré imported style of male dress and comportment.

The full-on macaroni was a top-to-toe affair: a virtual beehive wig, heavily powdered and perfumed; a long wig-bag and queue stretching down the back; a complexion beautified by makeup; a solitaire (bow) with pinked edges wrapped round the throat; a corsage of delicate flowers pinned to the lapel of a tight-fitting silk suit of some lurid hue—coral pink or pea green or deep orange or, in the painter Richard Cosway’s proud self-portrait, blue-and-mauve brocade with sprays of tiny roses; an exquisite waistcoat with floral patterns embroidered with gold or silver thread and sequins; dazzling buttons; striped silk stockings taking up where the outrageously short knee breeches left off; and red-heeled shoes with huge diamond-encrusted buckles. The essential accessories merely emphasized the artificiality of the whole get-up: the small hat was carried in the hand because it could not fit on top of the wig, and the highly decorated hanger sword whose top jutted out at waist height was more phallic than frightening.

To us, the most extreme aspect of this kind of display is the in-your-face expression of wealth in a society in which huge numbers of people were chronically malnourished. McNeil points out that at a time when Thomas Gainsborough was charging 60 guineas for a full-length portrait (about $10,000 in today’s money), Lord Riverstone paid almost half that for a single scarlet velvet suit made in Paris. But in eighteenth-century English culture, questions of social justice were not prominent in criticism of style. As the fashion historian Aileen Ribeiro puts it in relation to the macaronis, “Vast expenditure was less the problem than the correct—understated—aesthetics of display.” Not just the aesthetics, however. The macaronis, only ever a small elite, occupied a disproportionate space in the British public sphere because they literally embodied a profound disquiet about English manliness.

Much of this anxiety had to do with English uncertainties about fashion itself. On the one hand, sumptuary legislation restricting luxury goods had long been abandoned in England, and this could be seen as an expression of English liberty that contrasted favorably with autocratic France. Eccentricity was celebrated by the English themselves as a peculiarly English trait, a marker of individual freedom, and there was no reason why this should not be extended into the realms of dress. Indeed, some of the original macaronis could be seen as great exemplars of the power of individualism in politics and scientific endeavor. Charles James Fox, the leading radical Whig parliamentarian, was depicted as “the Original Macaroni”—in his twenties he was to be seen “strutting up and down St. James’s street, in a suit of French embroidery, a little silk hat, red-heeled shoes, and a bouquet nearly big enough for a may-pole.” Likewise the pioneering botanist Sir Joseph Banks, a world traveler who accompanied Captain James Cook on the voyage of the Endeavour, was depicted by the printmakers as “the Fly Catching Macaroni.” Neither Fox, a notorious heterosexual, nor Banks, an intrepid explorer, could reasonably be seen as unmanly.

Advertisement

On the other hand, the term “slave to fashion,” which we still use, had highly political overtones. The French, in the common English view, were followers of fashion because they were followers. The need to adopt the latest style, however absurd, was evidence of the French servility that contrasted so miserably with the Englishman’s vigorous independence of mind. Alarmingly, therefore, the evidence of Englishmen becoming Frenchified followers of fashion even while England was in a state of semipermanent war with France pointed toward an erosion of Englishness itself. The macaronis could be seen as a cultural fifth column: today coral-colored coats, tomorrow a Bastille in Westminster. A broadside published in 1777 called for the banishment of the “refinement” that had come from the Continent to “taint the ENGLISH mind”:

Send back the Siren to her native shore,

And make each BRITON great, as heretofore;

No longer slaves to FASHION let them be,

But like their fathers, generous, bold and free…

McNeil might usefully have pointed out that these fears were not new. Christopher Marlowe’s tragedy Edward II, written almost two centuries before the macaroni craze, shows the English state infected by the foreign vices of luxury, ostentation, and sodomy, then understood more as Italian than French. Here, too, showy foreign clothes are the flashpoint. Young Mortimer’s rage at Edward’s male lover, Piers Gaveston, springs not just from sexual disturbance but from Gaveston’s flamboyant and explicitly un-English garb and—even worse—his unforgivable sin of laughing with the king at Englishmen’s lack of fashion sense:

I have not seene a dapper jack so briske,

He weares a short Italian hooded cloake,

Larded with pearle, and in his tuskan cap

A jewell of more value then the crowne.

Whiles other walke below, the king and he

From out a window, laugh at such as we,

And floute our traine, and jest at our attire.

Much later—but still before the term “macaroni” was first used in 1757, in David Garrick’s play The Male-Coquette—we have (as McNeil does point out) Whiffle, the sea captain in Tobias Smollett’s very popular picaresque novel The Adventures of Roderick Random (1748):

A white hat, garnished with a red feather, adorned his head, from whence his hair flowed upon his shoulders, in ringlets tied behind with a ribbon. His coat, consisting of pink-coloured silk, lined with white, by the elegance of the cut retired backward, as it were, to discover a white sattin [sic] waistcoat embroidered with gold, unbuttoned at the upper part to display a broch set with garnets, that glittered in the breast of his shirt…the knees of his crimson velvet breeches scarce descended so low as to meet his silk stockings, which rose without spot or wrinkle on his meagre legs, from shoes of blue Meroquin studded with diamond buckles that flamed forth rivals to the sun!

Whiffle’s entourage leaves “the air…impregnated with perfumes” as it passes and he himself is so offended by the smell of a mariner that he has to be revived by his French valet de chambre, Vergette. Whiffle is also homosexual—he arranges for a young surgeon called Simper, whose face is coated in makeup, to sleep in the cabin next to his, giving rise to scandalous rumors among the crew, who “accuse him of maintaining a correspondence with the surgeon not fit to be named.”

In all but his hair, which seems to be natural rather than a wig, Whiffle is a macaroni avant la lettre. Does it make sense, then, to see the rise of the macaronis as a distinctive cultural moment? One way to suggest that it does is to consider poor Bob Acres in perhaps the most delightful of eighteenth-century plays, Richard Brinsley Sheridan’s The Rivals, first produced in 1775 when the macaronis were strutting their stuff. Acres is a country squire who has come from Devon to the fashionable resort of Bath in a doomed attempt to woo the lovely Lydia Languish. We see him first in his sensible country gear, but he declares his intentions to transform his appearance (interestingly using military metaphors whose comic inaptness plays on fears of the emasculation of the militia):

I’ll make my old clothes know who’s master. I shall straightway cashier the hunting-frock and render my leather breeches incapable. My hair has been in training some time…and tho’ff the side-curls are a little restive, my hind-part takes to it very kindly.

When we next see Acres he is indeed done up in the macaroni style. And two of Sheridan’s best jokes, both now rather obscure, illuminate the particular anxieties of the macaroni moment. First, there is the idea of the English male body being possessed by French affectations. Bob, in his new gear, is learning to dance in the French manner, a torment he experiences as a kind of invasion by alien movements and language:

Advertisement

Mine are true-born English legs; they don’t understand their cursed French lingo! Their pas this, and pas that, and pas t’other! Damn me, my feet don’t like to be called paws! No, ’tis certain I have the most antigallican toes!

Though now lost on us, “antigallican” is the great joke here. The Laudable Association of Anti-Gallicans had been founded by a group of London tradesmen in 1745 to resist the import of French clothing and manners. As Michael Cordner has put it, “it regarded the adoption of French fashions and styles as a form of cultural treason and a profligate pollution of national identity.” The antigallicans succeeded in having the importation of French silks to England banned in 1766. Yet—and this is the cause for alarm—the dictates of fashion forced the English beau monde to defy the ban. Fashionability overrides even patriotism. The French body-snatchers have a firm grip on Bob Acres. He has no free will: his antigallican toes might wish to lead him in one direction but his dainty new shoes point in quite another.

The other joke comes from David, Acres’s valet. Seeing his master in his gaudy array, he gushes compliments that are innocently backhanded:

You are quite another creature, believe me, Master, by the mass! An we’ve any luck, we shall see the Devon monkeyrony in all the print-shops in Bath!

This exposes two raw nerves: the fear that differences of gender are being eroded by the appearance of a new kind of nonmale, nonfemale creature; and the strange way in which the macaroni phenomenon melds appearance and reality, self and performance.

Sheridan’s coinage “monkeyrony” is more than just another malapropism in a play that features Mrs. Malaprop herself. It conflates “macaroni” with “monkey” and evokes a history of representing the flamboyant homosexual as a creature who, being neither properly male nor female, must be seen as subhuman. To return to Whiffle in Roderick Random, the outraged Welsh mariner Morgan curses him in precisely these terms:

I will proclaim it before the world, that he is disguised, and transfigured, and transmogrified, with affectation and whimseys; and that he is more like a papoon [i.e., baboon] than of the human race.

McNeil, though he neglects Bob Acres, shows that there is a pattern of attacking the macaronis as apes or monkeys. In the words of one anonymous broadside: “I should suspect they had some relation to an Ape: For certainly they are of a mixt species, and often the beast predominates…” The mixture is a double one, French with English (the French were also often called baboons) and male with female. The unfortunate Acres, who is after all merely trying to court a woman, finds himself, in his valet’s inadvertent formulation, innocently venturing into minefields of impure nationality and unholy sexuality.

At issue is the English male body. While Acres’s now discarded hunting coat and leather breeches would have hidden his body, his macaroni dress reveals it. The short silk coat exposed in particular the backside, seat of sodomitical desires. The “jutting bum” of the macaroni was a specific object of scorn. McNeil reproduces a typical print entitled The Cold Rump or Taste Alamode in which a macaroni holds his arse to a fire. It both mocks the impracticality of his short coat in the cold English climate and hints at his attraction to forbidden pleasures for which he will burn in hell. This anxiety was related not just to homosexuality but to the broader idea of men using their bodies as sexual bait in the way that women did. In his Moral Lectures on Heads, Edward Beetham, while referring to a figure called (like Smollett’s) Captain Whiffle, claimed of the macaronis that “in order to avoid the ridiculous appellation of nobody, they are determined to be all-body, and therefore they have no skirts to their coat….”

What is specific to this period, moreover, is that the anxiety about men being feminized by their clothing went both ways. Women were also being masculinized, and again the militia played a large part in the imagining of this process. It became fashionable for women to attend militia displays in costumes made in the colors of their husband’s regiments. Fox’s great supporter, the Duchess of Devonshire, was depicted in the satiric prints in military-style riding habits. As one observer noted: “Female delicacy is changed into masculine courage, and as much of the [military] garb assumed as at first view almost leaves the difference of sex indistinguishable.”

While the macaronis were dumping their greatcoats, society ladies were adopting them—a fashion that, ironically, spread from England to France. It was not entirely welcomed in either country. As Aileen Ribeiro writes in her magisterial The Art of Dress: Fashion in England and France, 1750 to 1820:

The greatcoat [in France] could be converted into the chic redingote, but the French were not accustomed to see women wearing riding habits as a walking costume, which was the case in England—it was too obviously a sportif, masculine garment. Even in England there were grumbles that greatcoat-dresses and riding habits, along with the new low-heeled shoes, gave women more freedom of movement to indulge in swaggering masculine deportment.

If Bob Acres is led into this dangerous territory of gender confusion, his servant’s enthusiasm also points us toward the other distinctive aspect of the macaroni moment—the self-reflexive quality that, two hundred years later, would have been called “post- modern.” When David tells his master that, with luck, “we shall see the Devon monkeyrony in all the print-shops in Bath!,” he means that Acres may get to see himself caricatured by a printmaker as “the Devon Macaroni” in the way that Fox was as “the Original Macaroni” or Banks as “the Fly Catching Macaroni.” This ought to be a horror—why would Acres want to have his image displayed for public ridicule?—but David presents it as a most desirable prospect. This is, moreover, an accurate expression of the peculiar visual ecosystem in which macaronis imitate caricatures of macaronis and audiences in the theater and on the streets recognize macaronis because they have seen (and perhaps purchased) the prints. Macaroni does not just imply conspicuous consumption—it is itself conspicuously consumed, not least by its own devotees.

The macaronis were new, less because of who they were than because of how they were represented. As Ribeiro comments, “The sartorial absurdities of the macaronis with their towering wigs and tiny hats might only have been a footnote in the history of dress had their styles not coincided with the first generation of English caricaturists.” But instead of laughing the macaronis out of their orange silk breeches, the visual satires and theatrical burlesques seem to have confirmed them in their ways. A 1772 print reproduced in McNeil’s book shows ridiculously dressed men examining images in the window of a printshop, every one of them a caricature of a macaroni previously published by the same print sellers. As McNeil points out, with an acuity typical of his reading of these images, one of the men is actually looking at a cartoon of himself displayed in the shop window.

When we have prints of prints and “real” macaronis looking at parodic images of themselves, where is the self? Satire is defeated, its claim to moral superiority replaced by a dizzying symbiosis: the caricaturist needs the macaroni to exist and the macaroni’s existence is validated by the caricature. The style is all performance—McNeil notes that at the public masquerade balls, where others wore fancy dress, the macaroni men “went as ‘themselves.’” They had already rendered those selves exuberantly exotic and shamelessly artificial. They might have said, with Henry James’s Madame Merle in The Portrait of a Lady, “I know a large part of myself is in the clothes I choose to wear.” For Bob Acres to be mocked as “the Devon Macaroni” would be a triumph of transformation, proof that his old plodding English self had been discarded along with his hunting coat and leather breeches. Inside this comedy lurks a dark possibility: if there is no real self, there is no fixed character and thus no English national character to be defended from the French.

The wonder is not that the macaroni mode did not last but that it endured for as long as it did. There were so many reasons to hate it. Ordinary English people despised the macaronis for their apparent Frenchness and aggressive extravagance. (The namby-pamby Frenchified man being beaten by a good stout English fishwife is a favorite image.) Their affectation was at odds with the growing cult of the natural promoted by Rousseau. Their disruptions of gender and national identity were a danger in time of war.

The American and French revolutions promoted democratic ideals whose partisans were known as “Crops” or “Croppies” because they wore their hair cut short instead of tucked under the elaborate wigs of the macaroni. Sans-culottes would, for a time, edge out the wearers of silk knee breeches. Even while Bob Acres is trying to keep up with the fashion, the prologue of the same play, The Rivals, has two coachmen discussing the new vogue for natural hair: “Od’s life, when I heard how the doctors and lawyers had took to their own hair, I thought how ’twould go next.” By the 1780s, the “Original Macaroni,” Charles James Fox, had turned away from fabulous ostentation of dress and adopted an equally ostentatious slovenliness that marked him, in the eyes of his radical admirers, as the natural man of the future.

Writing in 1818, William Hazlitt declared in his essay “On Fashion”: “The ideas of natural equality and the Manchester steam-engines together have, like a double battery, levelled the high towers and artificial structures of fashion in dress.” The high towers of the macaroni wigs had indeed fallen by then, and the more sober styles of the rising merchant classes would eventually be adopted even by royalty. Gender differences in dress would be further exaggerated and more successfully enforced. Provoking the lower orders by sashaying in brazenly expensive outfits seemed less like a good idea.

Yet the macaroni style did not really die. It contained, for all its absurdity, a dream of life as carnival, of the self as invention, of gender and nation as prisons to be escaped from. And it, too, was eventually democratized in England in the profuse colors and wild styles of Carnaby Street. For the eighteenth-century printmakers’ caricatures we might substitute the Kinks’s 1966 hit song “Dedicated Follower of Fashion” without losing much of the same satiric intent:

He thinks he is a flower to be looked at

And when he pulls his frilly nylon panties right up tight

He feels a dedicated follower of fashion.

Fashion shrugged off such scorn in the 1960s as it did in the 1760s. Then as now it was wisest to criticize the dictates of fashion loudly while following them discreetly. If and when fashion so decides, we will see macaroni men again, not just on the streets but in parliaments and boardrooms.