According to the familiar adage, there are only two stories: a man goes on a journey and a stranger comes to town. It’s a catchy premise that falls apart when measured against one’s experience of literature. Yet I found myself recalling it after reading Keith Gessen’s excellent new novel, A Terrible Country. What if those two plots were in fact successive chapters in a single story? A man (or woman) goes on a journey and becomes the stranger in town. Isn’t that what happens in the novel of immigration?

A Terrible Country gives us this narrative arc—and plenty more—to consider. It inspires us to reflect on the indelible stamp that each historical era leaves on its survivors; the harrowing or amusing complexities of migration and repatriation; the challenge of understanding—and functioning in—a foreign culture; the dangers of assuming that one does understand that culture; and the relative merits of beneficent socialism, Communist dictatorship, and cowboy capitalism-gone-rogue. At the same time the novel’s narrative voice is so conversational, so laid-back and low-key, that it may take the reader a while to register the scope and ambition of Gessen’s project: how much he attempts and accomplishes.

That voice belongs to Andrei Kaplan, who at six left the Soviet Union with his family and who has become thoroughly Americanized—that is to say, he’s clinging to the lower-lower-middle rung of the American dream. A student of Russian literature whose academic career dead-ended before it began, sharing an apartment with roommates after a romantic breakup, he’s “desperate to leave New York”:

The last of my old classmates from the Slavic department had recently left for a new job…and my girlfriend of six months, Sarah, had recently dumped me at a Starbucks. “I just don’t see where this is going,” she had said, meaning I suppose our relationship, but suggesting in fact my entire life. And she was right: even the thing that I had once most enjoyed doing—reading and writing about and teaching Russian literature and history—was no longer any fun. I was heading into a future of half-heartedly grading the half-written papers of half-interested students, with no end in sight.

The failed academic, unlucky in love, is literary shorthand for “going nowhere.” So like Andrei, the reader is grateful and relieved when, in the opening pages, he gets a call from his older brother Dima, a Moscow wheeler-dealer and would-be plutocrat. Dima’s business affairs have necessitated an involuntary and temporary (or so Dima hopes) period of exile in London, and he needs Alexei to return to Russia to care for their grandmother, Baba Seva, who is almost ninety, lives alone, and is in precarious health.

Andrei, whose Russian is serviceable but rusty, has suffered through previous trips to his native land, grad school summers spent in a city marked by poverty, petty crime, urban decay, and paranoia. During one such visit, he ritually arranged his brightly colored American toiletries (razor, shaving gel, antiperspirant) as a kind of magic charm and personal protest against the bleak, post-Soviet-era grayness: “The colors were brighter and more attractive than anything I saw around me…. I felt like James Bond practically, with my little kit of ingenious devices.”

By 2008, when the novel begins, the world may be on the brink of financial crisis, but Moscow is doing great. With the hyperalertness that comes with being in a new place, Andrei notes the differences between the recent past and the present, changes he observes even before he leaves the airport: “As long as I’d been flying in here, they made you come down to this basement and wait in line before you got your bags. It was like a purgatory from which you suspected you might be entering someplace other than heaven.” Now, however, the cheerful airport guards have good haircuts and are chatting on “sleek new cell phones”:

Oil was selling at $114 a barrel, and they had clobbered the Georgians—is that what they were laughing about?

Modernization theory said the following: Wealth and technology are more powerful than culture. Give people nice cars, color televisions, and the ability to travel to Europe, and they’ll stop being so aggressive. No two countries with McDonald’s franchises will ever go to war with each other. People with cell phones are nicer than people without cell phones.

I wasn’t so sure. The Georgians had McDonald’s, and the Russians bombed them anyway.

On the train to the city center, Andrei is afraid he’s about to be mugged by a fellow passenger, who asks Andrei about his cell phone. But their conversation ends when the Russian is appalled to hear that Americans can’t find a way to weasel out of their cell phone contracts: “A person who couldn’t figure out how to dump an iPhone contract was not worth knowing.”

Advertisement

Andrei’s reunion with his widowed grandmother is affectionate and touching. Formerly a lecturer in history at Moscow State University until she was forced from her job “at the height of the ‘anti-cosmopolitan,’ i.e., anti-Jewish, campaign,” Baba Seva quizzes her grandson about his life in New York, and they discuss her chances of being invited to her best friend Emma’s dacha. So we are as shocked as Andrei when their lively conversation takes a precipitous turn for the worse:

“Andryusha,” she said. “You are such a dear person to me. To our whole family. But I can’t remember right now. How did we come to know you?”

I was momentarily speechless.

“I’m your grandson,” I said. There was an element of pleading in my voice.

From this point on, Baba Seva’s health becomes a worry for the reader, as it is for Andrei and Dima. For long stretches of the novel, that anxiety recedes, then reemerges, altering Andrei’s perspective on his childhood, his current condition, and his own relatively manageable problems.

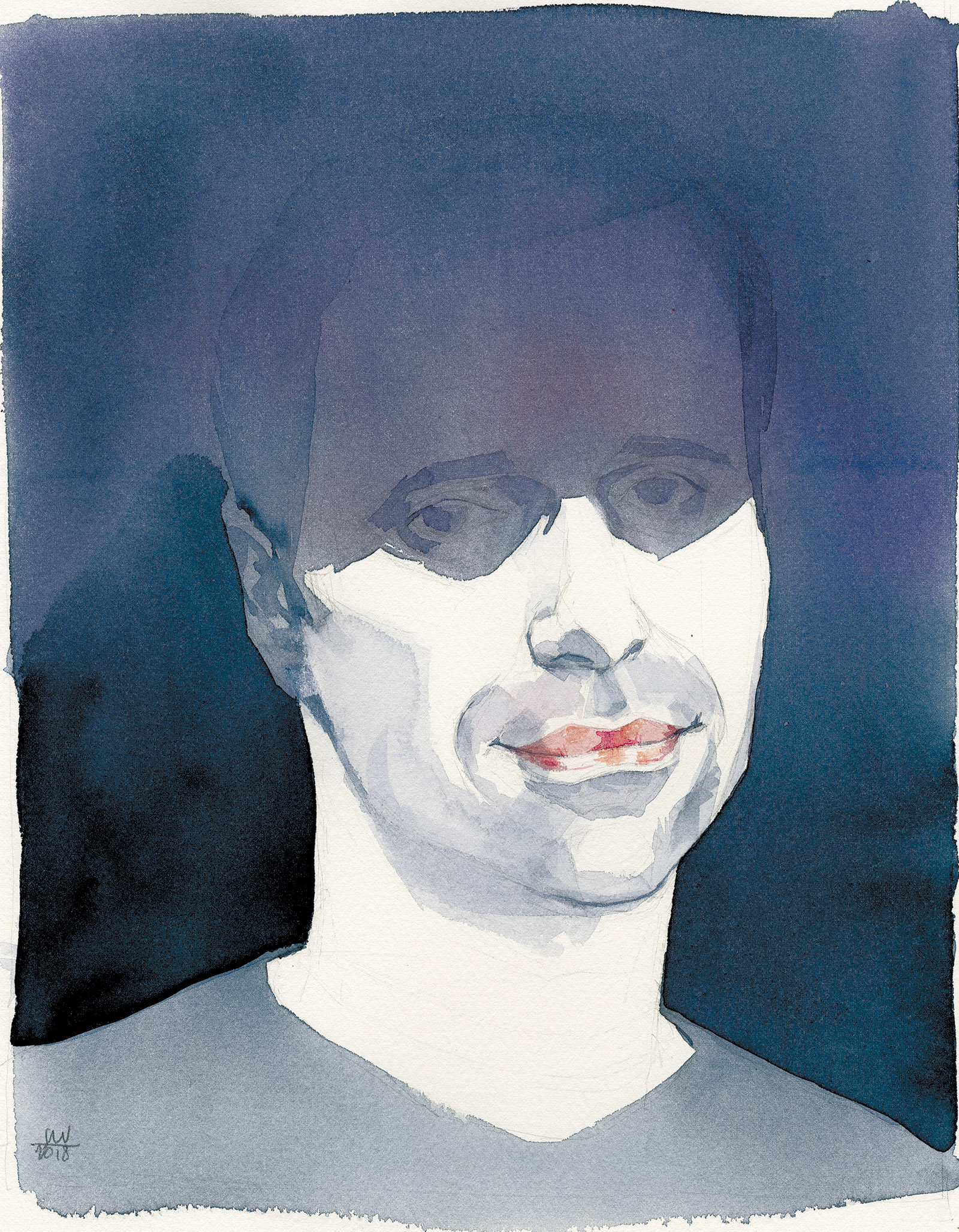

What saves all this from descending into sentimentality is that Gessen, a founding editor of n+1 magazine and the author of an earlier novel, All the Sad Young Literary Men (2008), has made Baba Seva an engaging character. She’s part of a cohort of preternaturally tough old women who survived the twentieth-century disasters—exile, death, persecution, starvation—engineered by Hitler and Stalin. It’s a type that readers may recognize from the work of Nadezhda Mandelstam, the author of two of literature’s most eloquent memoirs, Hope Against Hope and Hope Abandoned.

This is a terrible country is Baba Seva’s furious, sincere opinion of Russia. Why did Andrei come here? The rest of the novel will track his shifting sense of how right or wrong she is. There’s a lot that Andrei can’t piece together about his grandmother’s past:

I didn’t know what had happened to Aunt Klava [an elderly relative of Baba Seva]; nor what her life has been like after the war; nor whether, before the war, during the purges, she had had any knowledge or sense of what was happening in the country. If not, why not? If so, how did she live with that knowledge? And how did she live in this apartment with that knowledge once that knowledge came?

By the final chapters, most of these questions will have been answered, and Andrei’s newly acquired information affects his understanding of his family and of the history that still shadows the glittery urban scene. Obliged to stay in Moscow by his need to take care of Baba, and lacking any practical alternatives back home, he is no longer a privileged tourist but a poor immigrant who can’t afford the city’s shatteringly expensive bars and cafés:

Everyone in Moscow seemed to drive a black Audi and there were websites where you could order a prostitute after reading all her customer reviews…. Every time I walked into the Coffee Grind and bought the cheapest item on the menu, I was amazed at all the other customers…. These people were buying a couple of double espressos and pastries and sandwiches and being charged thirty dollars. The worst part was, they didn’t even argue! You’d have thought some of them at least would have said, “What?” None of them said it. They handed over the money. They didn’t even blink.

Andrei earns a meager living teaching college literature courses on the Internet, a job that requires him to spend hours at the one café where he can buy a reasonably priced cappuccino and that—unlike his grandmother’s apartment—has reliable Internet service. Like many new arrivals, he finds himself comparing his former home with his current one. “In New York during rush hour the trains could be so crowded that people couldn’t get on, and had to wait for the next train. In Moscow when this happened, people got on anyway.” The men Andrei sees around him are

big, kasha fed, six feet tall, stuffed into expensive suits, balancing themselves on shiny, pointy-toed shoes, never smiling. Ten years ago you walked down a Moscow street and ran into a lot of thugs in cheap leather jackets. Those guys were gone now, replaced by these guys. Or maybe they were the same guys? They hogged the sidewalk; they barreled ahead without looking to see what was in the way; they kept their hands by their sides and their fists clenched, like they were ready to use them.

Determined to construct a viable life for himself in Moscow, Andrei makes tentative advances and suffers dramatic (and cautionary) setbacks. On a shopping trip to buy slippers for his grandmother, he finds a neighborhood ice rink where the hockey players allow him to join the game. Or at least they don’t stop him. Andrei’s a passionate hockey player, and the sport provides a way for him to make friends and improve his language skills. Meanwhile the city is teaching him things that he’d rather not learn. He’s pistol-whipped by a thuggish assailant who sees Andrei talking to his girlfriend. A foray into online dating reveals the steep price tag attached—the “cleaning fee” Andrei’s “date” demands in advance—for the wreck they will presumably make of her apartment.

Advertisement

At a dinner party he shouts “What have you done for Russia?!” at a visiting American academic of whom he is jealous. Impressed by his fervor, another guest, the attractive Yulia, asks him to “say a few words about the American system” at “a small discussion about neoliberalism in higher education” that she is organizing at a bookstore. After Andrei’s brief talk about the sorry plight of adjuncts in the United States, his new friend Sergei—the goalie on his hockey team—speaks at greater length:

What we’ve seen in Russia in the last twenty years is the replacement of a stagnant, sometimes violent and oppressive, but basically functioning state with a dictatorship of the market. People have died, of starvation, of depression, of alcoholism and violence, and not only have they done so quietly, they have done so willingly. They have praised their conquerors.

Sergei’s speech strikes Andrei with the force of a revelation. “Suddenly everything I had been looking at—not just over these past months in Moscow, but over the past few years in academia, and over the past fifteen years of studying Russia—became clear to me.”

Andrei joins a socialist group that calls itself October. Its members convene to read and discuss Marx and to attend political protests. There’s an irony that Gessen well understands in a Marxist cadre meeting in the country that has witnessed one of the longest-lasting and most spectacularly failed Marxist experiments. But Andrei and his friends believe in the idea—the ideal—of a state in which labor and human rights are valued and the government works to improve its citizens’ well-being, health, and education:

We were steeped in memories of the violent Revolution and its even more violent Stalinist sequel…. But Russian socialists? That was different. From listening to Sergei I could tell that he did not need any lessons from me in Soviet history. He knew about the camps, the purges, the lies. But there was more to socialism, he seemed to be saying. It wasn’t just camps and insane asylums.

Of course, it’s not lost on the Octobrists that they are living under Putin, whose face on the TV makes Baba Seva so upset that Andrei must change the channel, even though she isn’t sure who exactly Putin is. Belonging to October alters Andrei’s view of Moscow and Russian society:

I found myself gradually but unmistakably looking at the world a little differently…. Cute cafés were not the problem, but they were also not, as I’d once apparently thought, the opposite of the problem. Money was the problem. It had always been the problem. Private property, possessions, the fact that some people had to suffer so that others could live lives of leisure: that was the problem.

Andrei falls in love with Yulia—a romance initially thwarted by the existence of her husband, a self-serving anarchist who dresses like a Moscow hipster dandy. After Andrei’s first night with Yulia, “Moscow changed for me forever. It went from being the terrible place where I was born to being—something else.” Leaving her apartment at three in the morning, he walks home in the cold and is exhilarated by “the terrible freedom of this place.” He understands how it might be possible to be happy in the city that had only lately seemed so inhospitable:

The Octobrists had carved a little path through Moscow that allowed them to enjoy it. None of them made much money, or even any. They couldn’t become full citizens of the consumer paradise that Moscow had become. But there were little cafés and bookstores and bookstore-cafés where you could sit and have tea or a beer for a couple of dollars and read Derrida for a few hours without anyone bothering you. Even critical theory, which had fallen out of fashion in the United States, was still cool here. It was the Moscow I had once hoped existed but couldn’t find. Now here it was.

But the more well-adjusted and assimilated Andrei feels, the more often, and the more pointedly, Yulia reminds him that he doesn’t understand what it means to be Russian. When Andrei criticizes the lighting in a basement cafeteria, Yulia fumes: “You have no idea how we’ve lived. You have no idea how valuable a place like this is.” Unable to deflect her anger, Andrei throws up his hands “like a person who was at the end of his rope, who felt like he couldn’t say anything without being attacked and so therefore had decided to say nothing.”

The frustrations of dealing with Yulia’s disapproval lead to another turn—a downturn—in Andrei’s view of Russia:

I wasn’t sure I could handle being in the constant presence of someone so morally acute. I wasn’t sure I could live up to it. I was sure, in fact, that I could not.

More to the point, would I really be able to stay in Moscow indefinitely?… Just to do anything—to get my skates sharpened, to get a library book, to get from one part of the city to another—was an unbelievable hassle. What in New York took twenty minutes, here took an hour. What in New York took an hour, here took pretty much all day. It wore you down. The frowns on the faces of the people wore you down. The lies on the television, too, after a while, wore you down.

Events conspire to remind him that he is an outsider. He and a friend encounter a group of skinheads yelling, “Beat the Jews, save Russia!” When Andrei takes his grandmother to the park, the jovial old women hanging out on the benches turn out to be the mean-spirited anti-Semites that Baba Seva has said they are from the beginning. And yet, despite everything, Andrei’s infatuation with Russia continues:

I loved it. I loved kasha and kotlety and I loved the language and I loved the hockey guys and I even loved some of the people on the street. I loved walking down Sretenka with my hockey gear in my Soviet backpack, taking the subway one stop, emerging at Prospekt Mira and then walking to the stadium past the McDonald’s, the Orthodox church, the market where we failed to buy my grandmother slippers, and then into the rink. Late at night, on my way home, I loved sometimes buying half a chicken from the Azeri guys. “Our hockey friend!” they always said, greeting me. On nights when I went to see Yulia, I loved taking a car for three dollars—a flat one hundred rubles, who could argue.

Throughout the novel, Andrei has witnessed political protests, mostly from a distance, since his terrified grandmother pulls him away whenever she sees a crowd forming. And he’s participated in a potentially volatile though ultimately nonviolent demonstration. But a more confrontational protest—against a Russian oil company—leads to a pivotal scene during which things go badly wrong for Andrei, and disastrously wrong for his Russian friends.

It’s a bit difficult to understand why Andrei does what he does—especially because he himself isn’t certain: “I’ve gone over in my mind what happened next a fair amount, though maybe not as much as I should.” Is he simply naive? Is he acting from cowardice, willing to do “just about anything” to save his own skin, taking the easy way out of a perilous situation? The one thing that emerges most clearly is that Andrei really doesn’t know as much as he thinks he does about the country with which he has repeatedly fallen in and out of love. In the most important ways, he understands nothing at all.

Rescue comes via a less-than-persuasive plot turn, challenging us to believe that even the ferociously competitive academic job market is susceptible to near-miraculous intervention. But no matter. The book has already given us so much that we’re willing to go along with whatever it takes to dismantle the wall that Andrei’s career had hit. To his credit, Gessen never lets us forget that one can’t be saved from everything, and the reader, along with Andrei and Dima, continues to be a pained and helpless witness to Baba Seva’s decline.

In its breadth and depth, its sweep, its ability to move us and to philosophize without being boring, its capaciousness and even its embrace of the barely plausible and excessive, A Terrible Country is a smart, enjoyable, modern take on what we think of, admiringly, as “the Russian novel”—in this case, a Russian novel that only an American could have written.