It is an odd fact of publishing life that perhaps the most notable collections of art criticism to have appeared in recent times have been written by artists. In 2016 the painter David Salle brought out his criticism in How to See, and now Carroll Dunham, who is also a painter, has assembled his art writing in Into Words. Like How to See, it is a solid achievement. It, too, presents a number of reviews and essays we feel we will be turning to again in years to come; yet the two books are subtly different in tone.

From its very title, How to See sought a broad audience and came with a clear cause. The title said that the author was going to show us how to get to the essence of art and implied that not all art writing did so. Dunham’s title, though, is a little mysterious. It first suggests something tentative: that the author, a visual artist, is trying to get his thoughts across in a medium that is somewhat foreign to him. But Into Words can also mean that Dunham is, well, into words—that he likes writing. This interpretation is not quite right, either, but it is partially right, and it is what gives the book much of its life.

Carroll Dunham has a particular and often commanding voice as a writer. He can be brainy and erudite in one instance, and colloquial, amused, and down to earth in the next. Perhaps befitting Artforum magazine, where many of these writings appeared, his sentences are spotted with “somatized,” “neoteric,” “ontologically,” and the like. We hear of “the helix of codes that allow things to feel true” and the “youthful pulchritude” of some of Renoir’s subjects. He gets recondite with “pictures can’t reproduce (re-present) qualia,” and he flunked this reader (and his Webster’s Collegiate) with “uroboric conundrum.”

At the same time Dunham can explain a point with a reference to Tony Soprano, or can informally and quite rightly say of art in the latter part of the 1970s that the “juggernaut of modernism had already broken down and was being stripped for parts.” Sounding like a practiced journalist who knows he has to hook his audience immediately, he writes in the first sentence of an article that “Kara Walker’s work seems to have always brought out the worst in her.” Learned or hip, Dunham rarely gives us boilerplate, and in its precision and balance, he has a Dr. Johnson–worthy moment when he writes, concerning a work by William Baziotes, that “everything about this painting is ambiguous without being tentative.”

Dunham’s collection, which includes a lively and valuable introduction by Scott Rothkopf, is composed mainly of short and essay-length reviews dating from 1994 to 2015. There are also statements he has made about his work and conversations he has had at different times with the artists Peter Saul, Jim Nutt, Michael Williams, and Laurie Simmons, to whom he is married. The fullest and richest of these writings are Dunham’s reviews of such well-known figures as Robert Rauschenberg, Max Ernst, and Otto Dix, and he is equally good on Joe Zucker, the late Elizabeth Murray, and Barry Le Va—contemporary artists who may not be known beyond the art world. In each of these admiring but also objective and many-sided pieces we sense that Dunham is responding to artists whose work fed his own. But he is not emphatic about this.

Nor does he dwell on the upheaval in contemporary art that he has been associated with. Now sixty-eight, Dunham was part of the transformation in art that began in the late 1970s and early 1980s, when—to streamline a complex story—painting, after years of being frowned upon as an art form by many artists, progressive academics, and graduate school art teachers, again became a forceful way to make art. It was when, moreover, numerous young artists, including artists who worked with cameras instead of oil and canvas, returned to making not only representational pictures but artworks that caught the textures and issues of contemporary life. It could seem as if the very thrust of modern art, and certainly the progression into increasingly abstract, virtually incorporeal works exemplified by Minimalism, video, and Conceptual Art, was being questioned, even rebuffed.

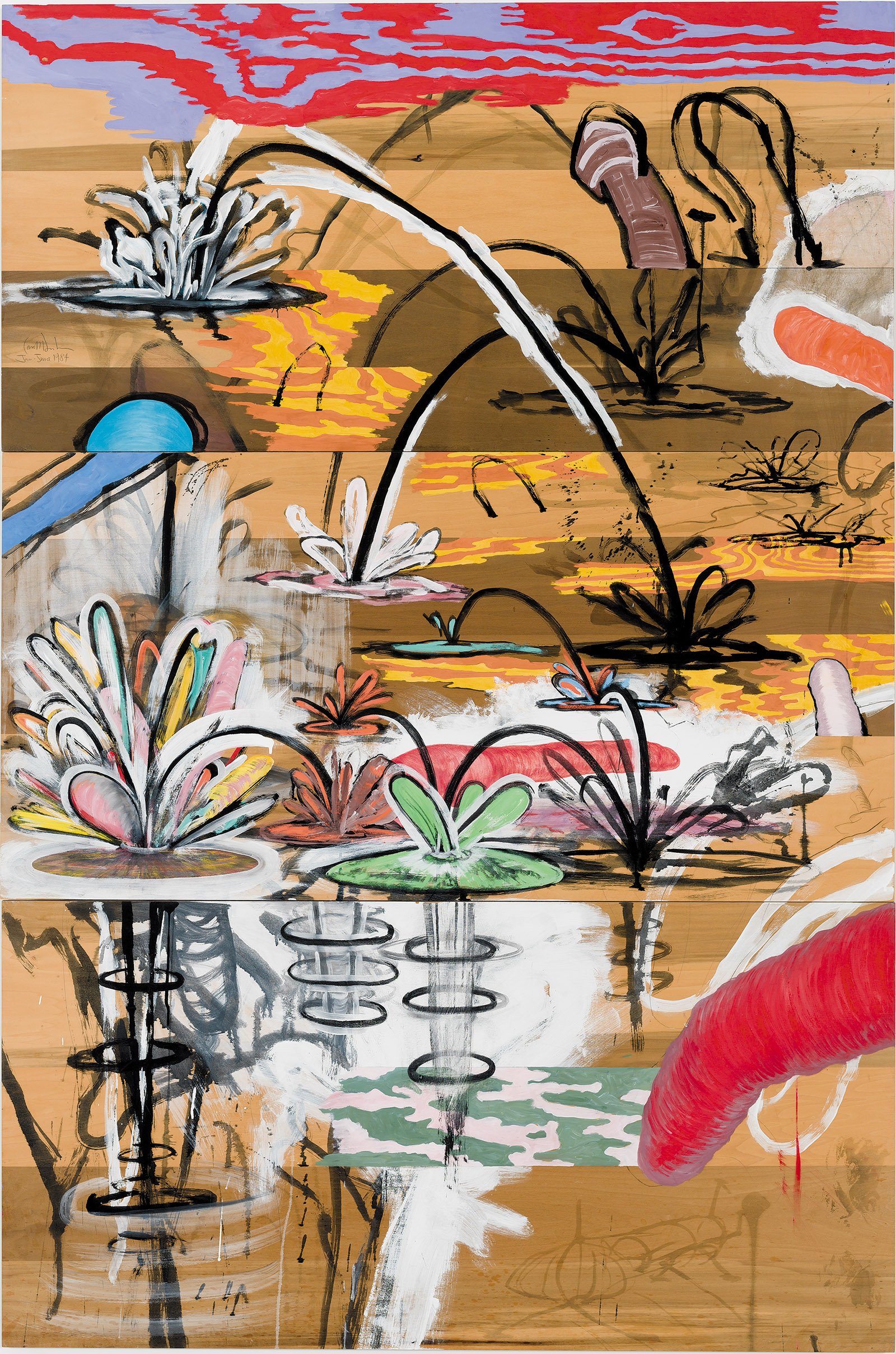

Dunham has never been as widely known as other figures of this disruptive moment, whether David Salle, Julian Schnabel, Cindy Sherman, Eric Fischl, or Jean-Michel Basquiat, perhaps because, when these figures were becoming known in the 1980s, Dunham’s pictures at the time were not the sort to make an immediate impression on a wider gallery-going audience. In those years, it wasn’t entirely clear what camp Dunham was in. His early paintings were somewhat like distant cousins of Cubism. Like Cubist pictures, they presented bits of recognizable things set within an abstract flow of lines. Some of those things resembled roots or exploding water lilies. Other shapes were definitely penises, and sprays of ovoid forms had an ejaculatory presence.

Advertisement

Yet in time these works, which were painted on wood panels and drew attention to the wood graining, have grown in power. With their exuberantly strong but also festive, decorative colors and dynamically varied, ever-shifting linear patterns, these early Dunhams now appear to be, at least for the present writer, among the gems of American late-twentieth-century art. The catalog that presents the core of these pictures, Carroll Dunham: Paintings on Wood, 1982–1987, from an exhibition held in 2008, has given me more sheer visual pleasure than almost any art book I own.

Not that Dunham’s work went downhill from there, and not that he remained an artist whose spirit was muffled. In the four decades that he has been exhibiting, he has continued to develop an art that is distinctively his own. In his pictures, the loose-limbed, often black-outlined forms we associate with cartoon animation—and a love of the textures available in whatever medium he uses—are brought together with a bristling, risk-taking, sometimes scabrous, and wry imagination. In Into Words he writes at one point that “it is forever shocking that Bosch could see what he saw when he saw it,” and in some sense Dunham is a Bosch for us now. His subject isn’t bizarre, dreamlike incongruities. It is the promptings of impish, demonic, or merely toxic visitors from no-no land who have taken up residence in our minds and are leading an active life there. Dunham is their biographer.

Though he doesn’t talk at length in Into Words about how his generation came about, he touches on the issue in tantalizing bits. When he says that “somewhat surprisingly, many of the significant developments in painting at the end of the twentieth century depended upon representations of the human figure,” one agrees that this is somewhat surprising and believes that it is accurate. It has also, I think, gone almost unnoticed by the majority of people concerned with contemporary art. At another point, looking at “eighties painting,” Dunham refers to “the more heroic elements of that decade’s residue,” and he astutely says (without elaborating on his point) that this is “an aspect much of the art world would prefer to forget.” In talking about Otto Dix, a painter Dunham appears to identify with, he captures an essential tenor of his own art and that of many of the artists who appeared on the scene when he did (and continued to appear, in a new wave of painters, in the 1990s) when he notes the German artist’s “confrontational conservatism.”

What keeps us reading Dunham, though, are passages and even phrases in which he comments on all sorts of art-historical developments, or on the ways artists think, or on how art touches us. He writes that in the 1970s, when Minimalism and Conceptual Art were flying high, “the generic vision of a good sculpture was a well-made gray box filled with fascinating ideas,” and elsewhere he says forthrightly that when “smart visual artists talk about their program self-deception is always a risk.” It is lovely, in another essay, to read that “when paintings outlast their creator they sustain a shard of consciousness from a vanished life.” Writing that “it’s a beautiful thing when artists move in surprising directions that are later deemed to have been inevitable,” Dunham’s subjects are change, movement, and awareness, and not necessarily artists at all.

Dunham might be describing the way his audience has come to see the surprising directions his own art has taken. Especially in his first decades, he seemed to be regularly reinventing himself as he went along. After making the pictures on wood that were largely abstract and yet contained vestiges of known things, he moved on to pictures that suggested pulsating, restless, hairy, or erupting blobs. Later there were pictures of bubbling, squarish entities that might be equipped with lips lolling here and there and shapes that were like shorthand for vaginas.

In the 1990s Dunham’s scenes became rife with aggressive humanoid figures that had immense teeth resembling windows, or tended to point pistols at one another. Instead of noses they might have penises, with tiny purselike scrotums for nostrils. Another group of pictures, presenting big rounded shapes ringed around the edges with these cranky, barking figures, suggested tormented planets. In other canvases Dunham’s squabbling stand-ins for people were found attacking one another in ships or growing out of high-rise apartments.

Advertisement

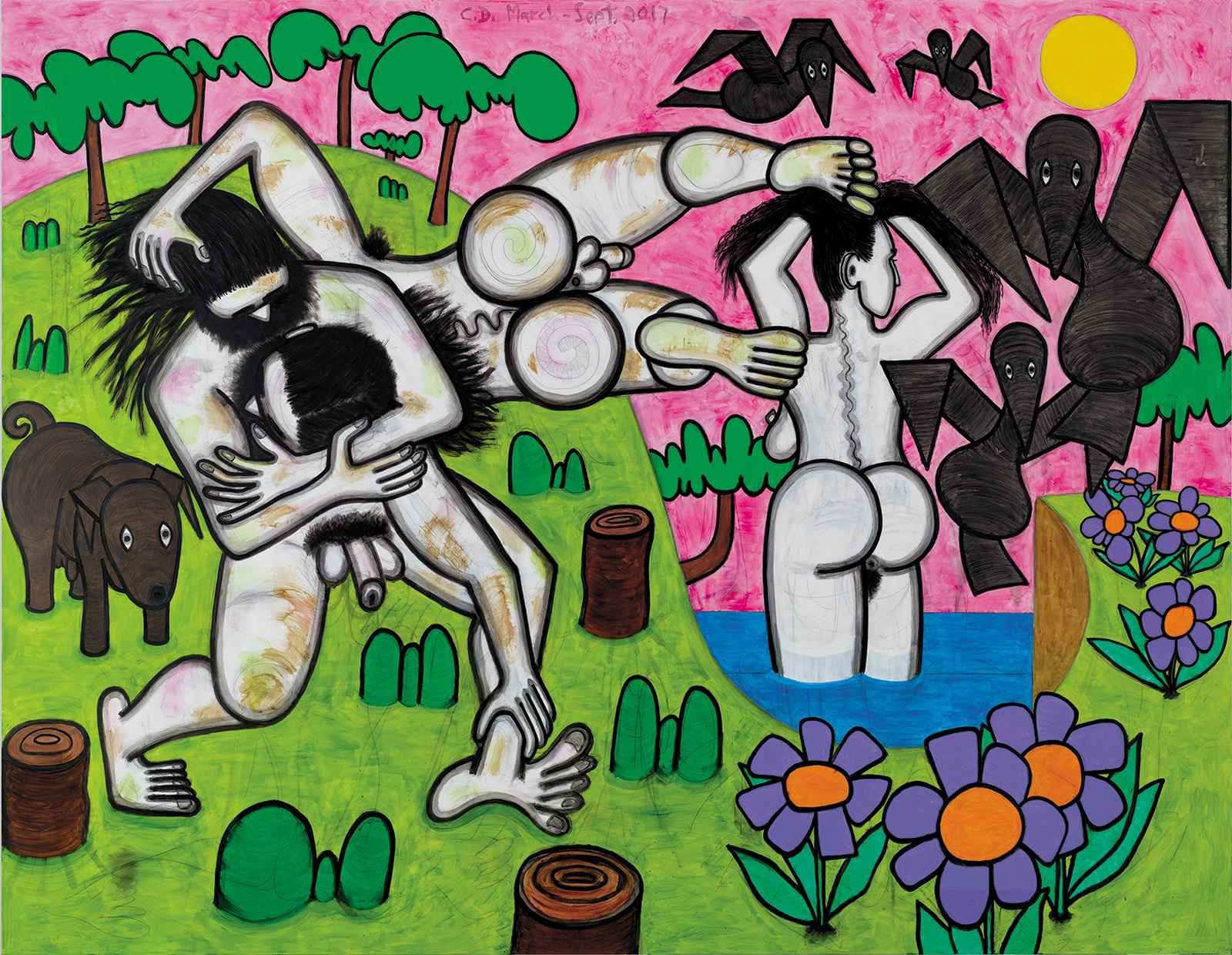

In recent years, Dunham has settled in (to the extent that this artist can settle in) as the chronicler of more fully formed human beings, usually seen in nature. The woman in these pictures is called a Bather and the men—they comprised a show this spring at the Gladstone Gallery in New York—are called Wrestlers. Female or male, they are totally naked and amply endowed with dreadlocks, muscles, and other body parts, namely breasts, buttocks, nipples, penises, scrotums, pubic hair, and anuses. These elements are pronounced. Nipples are so stiff and erect that they are little versions of the hats the Puritans wore. The paintings accordingly are so strange, daring, frisky, and, in an invigorating way, ridiculous that with each new exhibition of them Dunham has kept his audience as suspended as he did in his earlier years, when every group of pictures broke new ground. We are kept wondering how far he can take his convention-busting creations.

Yet there are probably few American artists whose various works, seen over a long course of time, feel, as Dunham’s do, so much of a piece. What possibly accounts for the sense that we look at a single, ever-evolving family of forms (and also spurs the outward variety of his pictures) might be called Dunham’s drawing self. As his many exhibited and published works on paper show, Dunham seems to draw with the unthinking ease and regularity of breathing. His paintings, for all their heightened color, are in some ways drawings writ large. In a scintillating 2017 essay about Dunham’s recent Wrestlers, the painter Alexi Worth, in one of innumerable pitch-perfect descriptions, refers to “teenagerish graphomania” as an element in Dunham’s artistic makeup. (Worth is, irritatingly, another accomplished painter-critic.)

Worth’s phrase hit me because Dunham’s pictures can seem, though not in any biographical, literal sense, like a monument to the kid who, in whatever grade school or high school class he was in, couldn’t stop drawing in his notebooks (or anywhere else) and who by definition was creating images that the teacher wasn’t supposed to see and everyone else wanted to see. Over the years, Dunham has seemingly let his doodling self, which he perhaps perceives as a gateway to his instinctive, deeper, and truer self, take him wherever it wants to go. It is important to note that Dunham is not a sketcher, which implies someone working from what is before the artist’s eyes. He is always, rather, on some level a doodler, which suggests someone working from what is in the artist’s head.

To hear it described, Dunham’s art can be considered that of a belated Surrealist—an artist waiting at the door of his semiconscious mind, expecting something libidinous, maybe unsavory, and, with luck, liberatingly unorthodox to walk out and take its place before him. Yet unlike most Surrealists, he is keenly concerned with form. His need is to play with his given theme, or image, in picture after picture until it is exhausted. The first time you see one of his characters with a top hat and a nose that is like a cross between a fairly erect penis and a kabob skewer with only one chunk of meat left on it you may find yourself simply giggling. But if you follow the permutations of this dickhead in picture after picture you find that he takes on a different life. He becomes a usable form. You see Dunham moving him around on the canvas or page to the point where he might be appearing sideways, or only his hat will be visible, and eventually he is hardly there at all. We watch as he becomes a spent motif.

It doesn’t take long, moreover, in absorbing Dunham’s Bather or Wrestler pictures to understand how genitals, nipples, and anuses for him are components in the overall architecture of the given scene. When he shows private parts, they are all standardized, cartoon-obvious, and generally outlined in black or are unmissable black dots. In effect, they are part of the scaffolding of strong lines and markings that make the pictures feel as if they are as much about ways to form balanced constructions as they are aggressive demonstrations of taboo-breaking and freakiness.

In his recent New York exhibition the strongest painting, the 2017 Any Day, in which Dunham’s tussling males share the stage with a Bather who has turned her back on them, is perhaps not a work that every museum (or maybe any museum) would be ready to hang at this point. Dunham’s people share the space of this large canvas with a goofy but observant dog, some hovering pot-bellied birds, and a third-grader’s idea of grass, sky, and flowers. Yet the painting exudes above all a compositional sturdiness and monumentality. If it is the progeny of any earlier artworks, a good candidate would be Léger’s public-spirited late pictures of workers and families.

What, in the end, does Into Words mean? My hunch is that Dunham’s title stems from the same desire on his part that viewers see the liberty-taking and the order-demanding sides of his pictures as going back and forth between each other at the same time. His title is an announcement of movement. It says that something—we don’t know what it is—is changing, in this case into words, before our eyes. His feeling for transitions and simultaneity may account also for his liking to conduct conversations with fellow artists and his including the conversations, counted as equals with his articles, in Into Words.

Even before this interpretation of Dunham’s title dawned on me, I found that some of the more striking passages in his writing were like little trips where sentences began in one place and landed at unforeseen other destinations. When he interviews Jim Nutt, for instance, he describes, exactingly, the painter’s home and Nutt the artist and person, and in back-to-back sentences he both times starts by looking at his subject one way and arrives somewhere else. Dunham says of the painter that “he has a friendly, modest aspect but with decidedly prickly undertones. One has the sense that he doesn’t suffer fools but is a bit unclear about how to identify them.”

The way both sentences turn at the ends can be heard in Dunham’s article about the pictures Picasso did in his last years, called Mosqueteros (Musketeers), which were shown in New York in 2009. Dunham at one point writes about the artist that “the megalomaniacal fantasies and narcissistic ideation that stalk the perimeter of many artists’ psyches must have seemed like reality to him.” The odd effect is that reality becomes merely another state of consciousness, and Dunham comes back to something like this thought, and this kind of sentence construction, in describing images created by Max Ernst: “These pictures of other worlds are like X-rays of our own, revelatory afterimages squirming behind the screen of reality.”

The “screen of reality” may be, on its own, Dunham’s most uncanny and audacious phrase, or notion. It is instantly destabilizing to think of reality as but a façade. But the words are also a kind of invitation, and they deftly evoke Dunham’s own art. Going “behind the screen of reality” is what we do when we look at his pictures.

This Issue

November 8, 2018

MLK: What We Lost

The Concrete Jungle

‘Inventing New Ways to Be’