I read the first two novels of Ali Smith’s seasonal quartet in Cairo, where long, warm, sunny days make up most of the year. In a city whose pace—a down-tempo lull—gives a sense that time is expanded, Autumn, with its meandering, time-traveling, light-footed story of a friendship between a young girl and an old man, felt exhilarating, deeply touching, even breathtaking. Winter, which is not strictly a sequel except in the seasonal sense and which revolves around a Christmas gathering at a family home in Cornwall, was fraught, overwhelming, dire. Too many people, too many egos, too many ideas, too much tension. “Ghastly” is how I have heard the season, which I have never experienced in its entirety, described—but the word “somewhat” applies to it and the temperament of the novel as well.

Winter begins tellingly, like Autumn, with a contemporary take on a Dickensian tale:

God was dead: to begin with.

And romance was dead. Chivalry was dead. Poetry, the novel, painting, they were all dead, and art was dead. Theatre and cinema were both dead. Literature was dead. The book was dead. Modernism, postmodernism, realism and surrealism were all dead. Jazz was dead, pop music, disco, rap, classical music, dead. Culture was dead.

As were history, politics, democracy, political correctness, the media, the Internet, Twitter, religion, marriage, sex lives, Christmas, and both truth and fiction. But “life wasn’t yet dead. Revolution wasn’t dead. Racial equality wasn’t dead. Hatred wasn’t dead.”

Smith, who was born in Scotland in 1962, is as attuned to the current moment as she is to the cycles of history that led us here. Growing up in council housing, Smith held odd jobs including waitressing and cleaning lettuce before persuing a Ph.D. in American and Irish modernism at Cambridge; she ultimately abandoned academia to write plays.

In Winter, Arthur (Art), who makes a living tracking down copyright-infringing images in music videos and also maintains a blog, Art in Nature, has just broken up with Charlotte, his conspiracy-theorist anticapitalist girlfriend, who has destroyed his laptop by drilling a hole through it and taken over his Twitter account to impersonate and ridicule him. Unable to face Christmas alone with his emotionally withdrawn, hypersensitive, and self-starved mother—Sophia, aka Ms. Cleves—and having promised her that he would bring along his girlfriend, he hires Velux (Lux), a gay Croatian whom he meets at an Internet café, to be a stand-in Charlotte (for £1000). At some point over that Christmas weekend, a long-estranged, politically and technologically aware hippie aunt, Iris, visits too. In their midst, accompanying Sophia, is the floating, disembodied head of a child. Bashful, friendly, nonverbal, it becomes something of a constant, if gradually dying, presence.

Family banter, conflict, political debate, reckonings, and reconciliation ensue. As do dreams, nightmares, hallucinations, and apparitions. Perspectives and narrators constantly change, shift, and collapse; parallel and tangential events are recounted at the same time. (“Let’s see another Christmas. This one is the one that happened in 1991.”) Conversation is structured and guided intuitively:

I cannot be near her fucking chaos a minute longer. (His mother talking to the wall.)

Lucky I’m an optimist regardless. (His aunt speaking to the ceiling.)

It is no wonder my father hated her. (His mother.)

Our father didn’t hate me, he hated what had happened to him. (His aunt.)

And mother hated her, they both did, for what she did to the family. (His mother.)

Our mother hated a regime that put money into weapons of any sort after the war she’d lived through, in fact she hated it so much that she withheld in her tax payments the percentage that’d go to any manufacture of weapons. (His aunt.)

My mother never did any such thing. (His mother.)

The events and the intricacies of the various interactions are both quotidian—“The walk from the gate to the house is unexpectedly far and the path is muddy after the storm. He puts his phone on to light the way. It buzzes with Twitter alerts as soon as he put it on. Oh God. So much for low reception”—and surreal. The plausible and the implausible are interchangeable, coming together in exuberant, tragicomic, and shrewd scenes:

Good morning, Sophia Cleves said. Happy day-before-Christmas.

She was speaking to the disembodied head…. The head was on the windowsill sniffing in what was left of the supermarket thyme. It closed its eyes in what looked like pleasure. It rubbed its forehead against the tiny leaves. The scent of thyme spread through the kitchen and the plant toppled into the sink.

At the dinner table and in allegory, tales are shared in multiple versions, forming a kaleidoscopic worldview and view of the family. An unreported chemical leak at a factory in Italy has killed trees, birds, cats, and rabbits, sent children to the hospital breaking out in boils, and poisoned the air, forcing everyone to leave their houses, which are then bulldozed. Sophia laughs at the vision of a cat with its tail falling off. Nobody else finds this funny. Smith’s characters navigate one another’s twisted humor and multidimensional takes on the world with various modes and tics of survival (the nervous laugh, the emotional withdrawal). Political and class divides mark every interaction, even the most intimate, and Winter brings out the perversity of privilege and choice:

Advertisement

What’ve you really been doing? Sophia said. Or have you taken idealistic retirement now?

I’ve been in Greece, Iris said. I came home three weeks ago. I’m going back in January.

Holiday? Sophia said. Second home?

Yeah, that’s right, Iris said. Tell your friends that. Tell them to come too. We’ll all have a fabulous time. Thousands of holidaymakers arriving every day from Syria, Afghanistan, Iraq, for city-break holidays in Turkey and Greece.

“None of my friends would be in the least interested in any of this,” Sophia responds.

Autumn set the precedent for Winter’s method of moral inquiry as well as for its use of found language and its form, which discards the conformity of sequence and layers fiction with contemporary political facts. This, as the seasons pass, is perhaps the only continuity, both within and between the novels. Characters don’t walk in from one book to the next, though references and preoccupations do. The pace picks up in Winter, possibly as Smith finds her creative stride. Remarkably, out of the abysmal state of world affairs she finds the capacity for inventiveness and play.

A master craftsperson, Smith seems to be completely liberated from ideas of what a novelist should be or do. There is no self-consciousness, no pretension. One has the impression that everything that meets her fancy, amusing or intriguing her, finds its way into her work. Wordplay, ideas on syntax, puns, banter with poetry and neologisms—“(What’s carapace?) It’s a caravan that goes at a great pace”—musings on images and representation, death, myth, painting, appropriation. As her characters turn to Google or the dictionary, one imagines she just did too:

She looked up at the consonants and vowels of what looked like a nonsense Scrabble game the people living here had painted round the room’s cornicing, still quite elegant regardless of the disrepair. i s o p r o p y l m e t h y l p h o s p h o f l u o r i d a t e w i t h d e a t h.

It is not by chance that Smith references art and artists so frequently in her work. (In her luminous 2014 novel, How to Be Both, the narrator of the historical novella that forms part of the narrative is the fifteenth-century Renaissance painter Francesco del Cossa; in Autumn, the iconoclastic 1960s British pop artist Pauline Boty is a shared fascination among the characters, as is the modernist sculptor Barbara Hepworth for Sophia in Winter.) While literary references seep through her novels, she also excavates and references histories of culture, politics, and art to come up with a language entirely their own. Smith’s novels are not so much prescient as they are intuitive and sensitive to nostalgia, the forces of collapse, and the breakneck speed with which we are hurtling toward further disaster.

She long ago abandoned traditional modes of storytelling. How to Be Both was printed in two editions, one with the historical narrator preceding a contemporary one, the other in reverse order. Before that came her fictionalized book of lectures, Artful, which was narrated by a character haunted by a former lover who writes a series of sharp lectures on art and literature, and the Booker finalist Hotel World, narrated in part by a spirit and the women around her affected by her death (it’s surreal, probing, compassionate, and witty all at once). Autumn and Winter, the first two in the quartet, are written in sort-of real time (think reality TV as novel) with stream-of-consciousness and political commentary coming together to form parallel narrative threads that connect the various characters, their actions, and the stories in their heads—past, present, future.

Smith seems to be attempting to write as fast as information and reality change, as fast as truth turns to fiction and fact is annulled. While letting her characters guide her—as well as guide and muse and struggle with themselves—she responds to current events that find their way into the story:

January:

it is a reasonably balmy Monday, 9 degrees, in late winter a couple of days after five million people, mostly women, take part in marches all across the world to protest against misogyny in power.

A man barks at a woman.

I mean barks like a dog. Woof woof.

This happens in the House of Commons.

The woman is speaking. She is asking a question. The man barks at her in the middle of her asking it.

More fully: an opposition Member of Parliament is asking a Foreign Secretary a question in the House of Commons.

She is questioning a British Prime Minister’s show of friendly demeanour and repeated proclamation of special relationship with an American President, who also has a habit of likening women to dogs.

Autumn was as attuned to political forces as Winter, but it seems to have been written in a state of slight shock or dismay—at the refugee crisis, the revolutions and fallen hopes in the Middle East, and the outcome of the Brexit referendum. It is breathless, too, but sadder, slower, and easier to take in. Winter moves with such ferocity that while reading it one is forced to pause, stand back, reread, and take a bird’s-eye view of the absurdity of what our culture has become: we battle to keep people fleeing war-torn countries out of our “homeland” for fear of what they might bring, how they might terrorize our lives, our jobs, our communities: “Ask them what kind of vicar, what kind of church, brings a child up to think that words like very and hostile and environment and refugees can ever go together in any response to what happens to people in the real world.”

There is the absurdity, too, of an age in which we adopt online avatars and take to Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram to share our thoughts, promote our work, curate our identities. Reading a blog post of Art’s, Lux clears her throat:

It doesn’t seem very like you, she says. Not that I know you that well. But from the little I know.

Really? Art says.

They are sitting in front of his mother’s computer in the office.

You don’t seem so ponderous in real life, Lux says.

Ponderous? Art says.

In real life you seem detached, but not impossible, she says.

What the fuck does that mean? he says.

Well. Not like this piece of writing is, Lux says.

Thanks, Art says. I think.

Meanwhile, on Twitter, “Charlotte is demeaning [Art] and simultaneously making it look like he is demeaning his own followers.” This manic unraveling, the pretense of Charlotte-as-Art and Lux-as-Charlotte, isn’t the future—it is our present.

Who are we, the bobbing child’s head begs us to ask, when we have lost who we were? The disembodied head, sometimes sad, sometimes simply looking on, might represent our pasts, or our conscience, or our lack of one:

How could it breathe anyway, the head, with no other breathing apparatus to speak of?

Where were its lungs?

Where was the rest of it? Was there maybe someone else somewhere else with a small torso, a couple of arms, a leg, following him or her about? Was a small torso manoeuvring itself up and down the aisles of a supermarket? Or on a park bench, or on a chair by a radiator in someone’s kitchen? Like the old song, Sophia sings it under her breath so as not to wake it, I’m nobody’s child. I’m no body’s child. Just like a flower. I’m growing wild.

Not that there aren’t glimmers of hope in these books. Political upheaval, and then revolution, change the very nature of our social interactions, splitting society, creating hierarchies, and dividing us into vehement tribal groups (Stay/Leave, pro-coup/pro–Muslim Brotherhood, Trump/anything else). But out of the fractures, the losses, even the mania (at Christmas, or at political breaking points like referendums or coups), we sometimes lose ourselves so completely that we eventually find common ground again. Lux, pretending to be Charlotte but acting with no pretense, disarms Sophia, who warms to her (and begins to eat). Art, skewered for pretension by someone no longer in his life, is forced to reckon with himself. Iris and Sophia, at political odds, so long estranged, reconnect through memories prompted by a song from childhood.

Winter is a novel about being alone, and of becoming more alone in an age of technology and manic ego, on the verge of exploding artificial intelligence. But it is punctuated with reminders of times past and what could still be salvageable. In one such section, Smith imagines “another version of what was happening” on the morning Winter describes:

As if from a novel in which Sophia is the kind of character she’d choose to be, prefer to be, a character in a much more classic sort of story, perfectly honed and comforting, about how sombre yet bright the major-symphony of winter is and how beautiful everything looks under a high frost, how every grassblade is enhanced and silvered into individual beauty by it, how even the dull tarmac of the roads, the paving under our feet, shines when the weather’s been cold enough and how something at the heart of us, at the heart of all our cold and frozen states, melts when we encounter a time of peace on earth.

One can imagine Winter—which is fast-paced and frenetic, sometimes to the point of exhaustion—being read eagerly some hundred years from now, in a future that tries to make sense of an Earth where much has imploded. In that future, it might appeal equally to the literary reader, if there still is one, and to the historian.

Smith’s quartet, so far, is not only an inventive articulation of the forces that have collided to make the present, but also a meditation on—and experiment with—time.* By structuring her books around the changing seasons in an epoch when the seasons themselves are unpredictable, even in question (“November again. It’s more winter than autumn”; “It will be a bit uncanny still to be thinking about winter in April”), she urges us to ask whether we can still save our planet, as well as future generations’ lives. It’s hard to imagine what Spring and Summer might bring—perhaps a complete halt, or inversion, of time awaits us—but the first two novels of the quartet are so free with form, as well as so morally conscious, that they come close to being an antidote to these times.

This Issue

November 22, 2018

A Very Grim Forecast

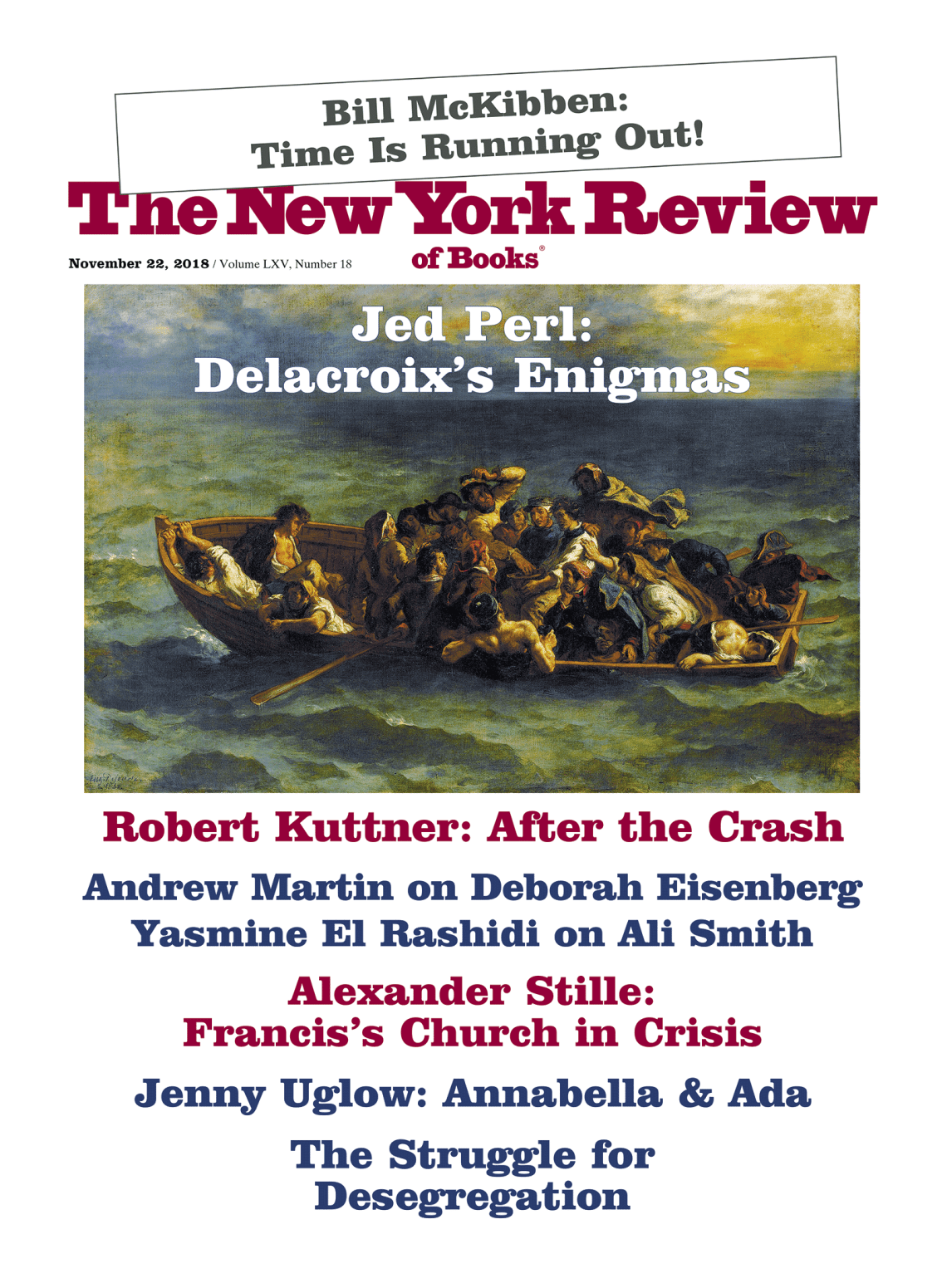

Romanticism’s Unruly Hero

The Crash That Failed

-

*

Spring will be published by Pantheon in April 2019. ↩