In the spring of 1974, my fifty-five-year-old father had a heart attack. He was rushed to a small community hospital in Queens. I was living in Manhattan, studying medicine at Columbia. By the time I arrived at the hospital, he was in shock, gasping for breath, his heart unable to pump forcefully. The hospital had no intensive care unit or cardiologist in attendance, no effective measures to compensate for his damaged heart. He died before my eyes.

Over the ensuing decades, although I am not a cardiologist, I’ve followed with interest the evolving treatment of heart disease. The incidence of fatal heart attacks has fallen dramatically since I lost my father. This is attributable in part to preventative measures like quitting smoking, healthier diet, exercise, and statin medicines, all of which reduce the risk of atherosclerosis—the buildup of plaque inside the arteries. Treatment of heart attacks also has improved with the advent of drugs that help dissolve clots in blocked coronary arteries. In addition, technology has advanced to the point that diseased coronary arteries can be mechanically opened with angioplasty and stents.

But with the improved survival rate from a heart attack has come a striking increase in the number of people with congestive heart failure. Damage to cardiac muscle may not be immediately fatal, but over time the weakened heart struggles to pump blood effectively. The circulatory system backs up, filling the lungs with fluid and starving the body of needed oxygen and nutrients. Debility and ultimately death ensue.

The greatest cost of congestive heart failure, of course, is the suffering and demise of patients. But society as a whole also bears a substantial economic burden: the direct and indirect costs of care in the United States, including hospitalization and medications, have risen to about $31 billion a year. This has spurred a search for more effective treatments.

The best option for people with severe congestive heart failure when medications stop working is a heart transplant. With current surgical techniques and potent drugs to prevent rejection, transplantation is often successful. But there is a dearth of donors. So what is the alternative? Patients look to devices to sustain them. This has been viewed as a straightforward engineering problem with an engineering solution: the body’s natural pump replaced with an artificial one. But unalloyed success has largely proven elusive for nearly half a century.

A month after my father died, I finished my courses in the classroom and began my training in the hospital. That included scrubbing in on open heart surgery, where I was exposed not only to techniques of bypassing diseased coronary arteries with grafts but also the argot of the surgical residents. Notable was the term “cowboy,” lauding a heart surgeon (typically a man at the time) who confronted the toughest cases undauntedly, scalpel always in hand. But the macho appellation could have a mixed meaning, suggesting aggressive care beyond what was reasonable and operating on diseased hearts in people too sick to survive. The rationalization for those lost after very high-risk operations was that “desperate diseases require desperate remedies.”

Houston, Texas, was a crucible of modern cardiac surgery, and the trope of cowboys and their approach to care came to mind reading Mimi Swartz’s Ticker. An award-winning journalist and the senior executive editor of Texas Monthly, Swartz depicts the quest to develop a successful artificial heart through a series of portraits of cardiac surgeons:

These are physicians who have less in common with your kindhearted family doctor than with the first people who crossed Everest’s Khumbu Icefall or took the first steps on the moon. Medical explorers, like all explorers, tend to be brilliant, obsessive, brave, and arrogant; many of them were and are ill-suited to societal norms, craving adulation while, at the same time, behaving in ways that don’t exactly build affection. Maybe they have to be all those things: you don’t really want the person who cuts into your heart to lack self-confidence.

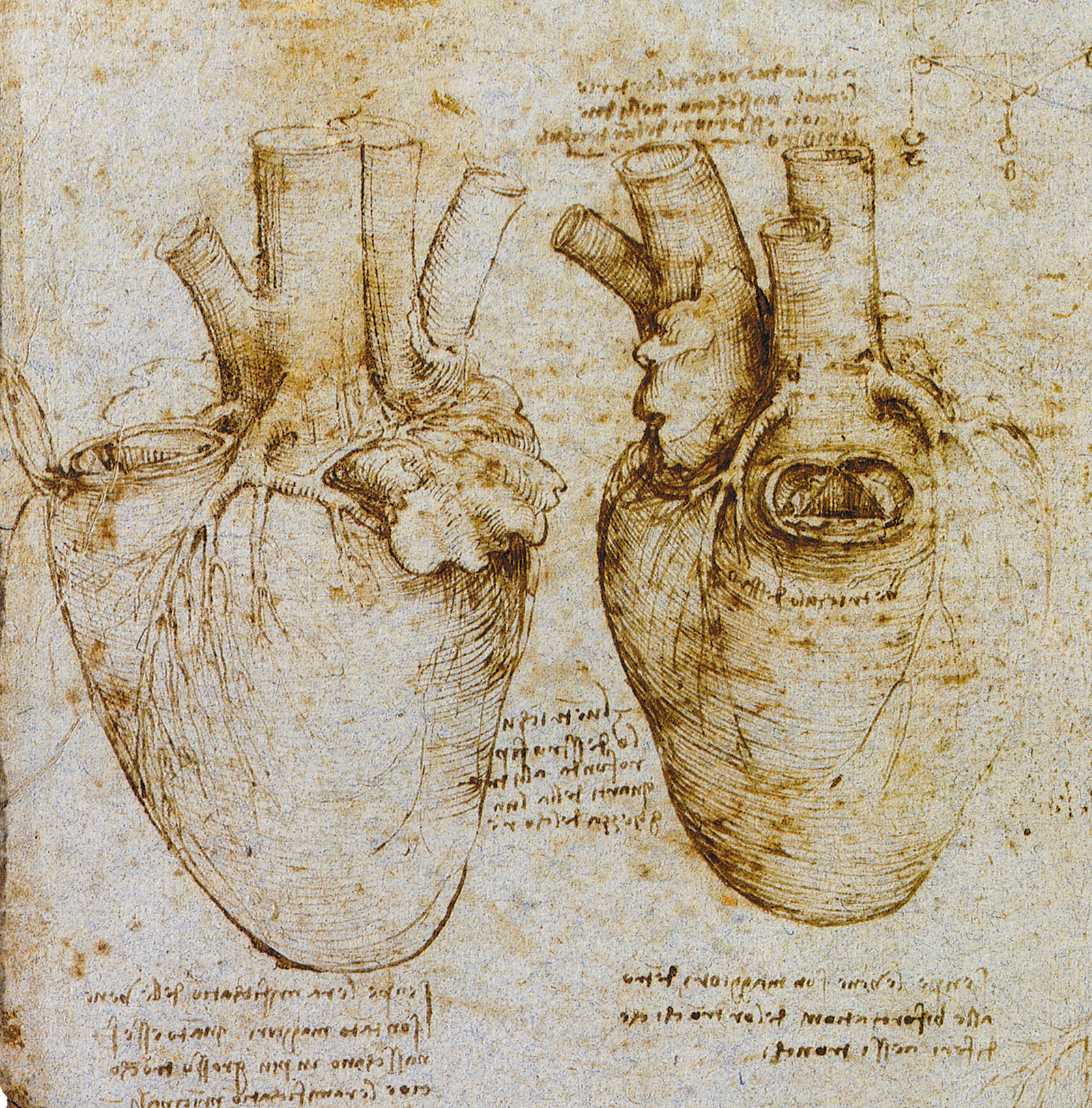

The aim of some of these surgeons, as Swartz puts it, is to create a device that replaces “the heart as a near-perpetual motion machine: it beats 60 to 80 times per minute, about 115,000 times a day, more than 2.5 billion beats in an average lifetime…. The heart keeps pace continuously, whether a person is running a marathon, making love, arguing with a coworker, or getting a good night’s sleep.” But a man-made “near-perpetual motion machine” does not operate in a conducive environment: it must interact with the complex currents and multiple types of cells of our bloodstream. Blood clots often develop in the pump, break off, travel to the brain, and cause strokes. Preventing these clots from forming with blood-thinning anticoagulants can result in massive hemorrhage.

Advertisement

This reality, predicted from studies of prototypes using animal subjects, did not deter surgeons from attempting to implant in humans an artificial device. In the 1960s two prominent cardiac surgeons in Houston, Michael DeBakey at Methodist Hospital and Denton Cooley at St. Luke’s Episcopal, raced to be the first to do so. In 1969 Cooley, who came from a wealthy and connected Texas family, was accused by DeBakey, the son of Lebanese immigrants, of stealing the design for his artificial heart pump and implanting it recklessly. Cooley’s attempt failed (the patient died within days), but his bold attempt made headlines across the nation.

The quest in Houston has continued over the ensuing decades. Swartz’s main character, Dr. Oscar Howard Frazier—“known to all as Bud”—a trainee of both DeBakey and Cooley, has led the effort at the Texas Heart Institute and its affiliate St. Luke’s, now named Baylor St. Luke’s Medical Center. “Bud still had one goal to accomplish before he hung it up: he wanted to see a working artificial heart become a reality, a total replacement that could be implanted and then forgotten,” Swartz writes. “Finally,” in 2015, “Bud felt that he was close.” Frazier is described in glowing language:

At seventy, he had a leonine mane of shimmering white hair and the unlined, luminous skin that came from spending the better part of fifty years indoors at the hospital…. Bud had also maintained an authentic West Texas drawl; he sounded to some like LBJ on Quaaludes. He lumbered a little, sometimes with a hitch in his step, the price of a high school football career in West Texas, along with years of standing for hours in the operating room…. Most people on the street might have taken him for a college history professor emeritus instead of a world-famous cardiac surgeon.

But Swartz believes that behind the veneer of an aging academic is a heroic warrior: “His life’s through line had become saving the unsavable.” At times, she does stand back from these encomiums and drops a cautionary note to the reader:

Bud Frazier likes to say that practicing medicine satisfies needs that are more metaphysical, for both doctors and their patients: “…Every primitive tribe has a Medicine Man,” meaning that in every era humanity wants to believe in its healers, who might be nothing more than salesmen with a good line.

In contrast to Swartz’s narrative told through the lives of famous surgeons, Shelley McKellar, a historian of medicine at the University of Western Ontario, offers a detailed study of social, cultural, and economic forces that propelled a series of “seductive devices”: artificial hearts that fell short of expectations. She situates the early visions of an artificial heart in

a period of great scientific and technological optimism in America, a time when the Congress endorsed many grand projects, including landing a man on the moon. Convinced of the scientific community’s ability to replicate heart function mechanically, National Heart Institute director Ralph Knutti predicted the availability of artificial hearts for clinical use by Valentine’s Day 1970.

This overpromising of scientific progress presages Nixon’s “war on cancer,” which aimed for a cure to coincide with America’s bicentennial in 1976.

McKellar poses profound clinical questions that extend beyond the artificial heart: “When is medical technology not the answer, particularly when it only ‘sort of’ works? When is it time to declare ‘No more!,’ and who gets to declare it?” She notes that for different but related reasons, the

“promises” of many new technologies may certainly have held more sway over the “pitfalls” for dying patients and their families, the device industry, and determined medical researchers. The characterization of artificial hearts as a “halfway success,” as stated by one bioethicist in the 1980s, reflected the many economic, social, and moral problems associated with the technology. It challenged the binary characterization of therapeutics as either successes or failures.

A “halfway success” occurred in 1982, not in Texas but in Utah, in the case of Barney Clark, a retired Seattle dentist with heart failure. His clinical course was closely followed in the media. After an initial positive outcome, celebrated in the press with photos of a beaming Clark next to his wife, he suffered a cascade of debilitating and ultimately fatal side effects, including gastrointestinal bleeding and multiple strokes. “Politicians, medical professionals, bioethicists, academics, and industry people weighed in, leading to increasing public disillusionment and vociferous debate over artificial heart technology,” McKellar writes.

Most outspoken against the clinical use of artificial hearts, bioethicists contested issues of informed consent and patient autonomy, access and cost, quality of life and patient self-determination, and the overall criteria for success. A discernible shift in medical and lay discussions was evident; once focused predominantly on the feasibility of developing artificial hearts, they now extended to the desirability of such a clinically acceptable device (perfected or otherwise).

The responsibility of the hospital’s Institutional Review Board (IRB), an oversight committee, came into tight focus. As McKellar writes about the IRB in Utah:

Advertisement

Its members took seriously their duties as ethical medical professionals…. They served as protector of the rights and safety of patients and needed to uphold the professional and ethical standing of their institution. They also did not want to stifle innovation at their hospital, nor deny potentially life-saving treatments to dying patients. The committee members all agreed that a stricter protocol needed to be worked out, most significantly a limiting of the potential patient population eligible for the experimental procedure.

How public money should be spent in combating heart disease also became a flashpoint. In 1988 the artificial heart was called “the dracula of medical technology” in a New York Times Op-Ed:

During its 24-year life this Dracula of a program sucked $240 million out of the National Heart, Lung and Blood Institute. At long last, the institute has found the resolve to drive a stake through its voracious creation. “The human body just couldn’t seem to tolerate it,” explains Claude Lenfant, the director of the institute. Starting with Barney Clark in 1982, artificial hearts have been implanted in four courageous patients in the United States and one abroad. Recipients would become such supermen, the technology’s enthusiasts had predicted, that they’d have to be barred from marathon races. But the crude machines, with their noisy pumps, simply wore out the human body and spirit. All patients suffered life of poor quality, often punctuated by strokes or seizures…. The artificial heart project started at the same time as the Apollo program to land a man on the moon. Unlike Apollo, it veered badly off course.1

This unsigned Op-Ed appeared shortly after Lenfant canceled federal funding for development of the device. Few people knew, McKellar notes, that he actually wrote it.

As Lenfant’s Op-Ed also noted, some “devices can be of temporary use in patients waiting for a heart transplant”; prominent Americans like Vice President Dick Cheney have benefited from the HeartMate II, a second-generation pump that assisted his left ventricle, to assure circulation throughout his body, rather than replace the whole heart. He lived with this implanted left ventricular assist device (LVAD) for twenty months before undergoing a successful heart transplant operation in 2012, and credited it with saving his life.

This past May, after the writing of Swartz’s and McKellar’s books, the Houston Chronicle and ProPublica published a series of investigative reports questioning the probity of the work of Bud Frazier, specifically how he selected patients for surgery and the veracity of his reports on experimental devices tested at Baylor St. Luke’s Medical Center.2 While the journalists acknowledged that his achievements have helped extend the lives of “thousands of people worldwide each year,” they claimed that “out of public view, Frazier has been accused of violating federal research rules and skirting ethical guidelines, putting his quest to make medical history ahead of the needs of some patients.” These serious accusations were based on examinations of internal hospital reports, federal court filings, financial disclosures, and government documents. “Frazier and his team implanted experimental heart pumps in patients who did not meet medical criteria to be included in clinical trials,” the Chronicle noted. A similar conclusion had been made by an internal hospital investigation a decade ago but never publicly disclosed. In fact, the hospital went so far as to report these research violations to the federal government and was required to repay millions of dollars to Medicare.

Dr. Frank Smart, a senior cardiologist who was at St. Luke’s between 2003 and 2006, is quoted by the Chronicle admiring Frazier’s commitment to developing lifesaving heart pumps, but believes it led him to surgically implant the devices into some patients who were not yet sick enough to justify what was, at the time, an experimental treatment. “In the old days of medicine…that’s the way these guys did things,” said Smart, reminiscing about Cooley’s first attempt. Now the chief of cardiology at Louisiana State University School of Medicine, Smart added, “It was, ‘Well, I have an idea, and I’m the one that knows best, and by golly, I’m going to do it.’ And did that advance the field? Maybe. Is it the right thing to do? Absolutely not.”

Other serious charges against Frazier included his turning down high-quality donor hearts for patients who had implanted experimental devices. Smart said that Frazier was “more interested in demonstrating how well the devices performed over longer periods. Unfortunately, that meant that some people didn’t get transplantation when that was probably a better option for them.” Distrust of Frazier was so extreme that Smart and other cardiologists resorted to “‘hiding patients’—moving them to other parts of the hospital…buying the patients time to recover with less invasive treatments or receive a transplant instead.” Two other former St. Luke’s doctors confirmed to the reporters this practice of hiding patients from Frazier.

Frazier has rebutted these accusations; he denies implanting devices in patients who did not need them and asserts that patients who required transplants received them when donor hearts became available. But at the time, executives at the hospital clearly were deeply disturbed by what was happening, the Chronicle notes. The executives

contemplated which scenario would be worse for the hospital’s bottom line and reputation: cutting ties with Texas Heart, the famed research organization founded 46 years earlier by Cooley, or continuing to be associated with the institute should the public ever learn about its research violations. “Should the affiliation be dissolved, the impact to St. Luke’s market position is unclear,” executives wrote, according to a summary report. “It is likely that such news would generate national attention and negatively impact our standing in the US News & World Report rankings.”

Based on the Chronicle’s investigation, it seems that Frazier’s surgical outcomes were among the worst in the country: “From 2010–15, about half of the traditional Medicare patients who received an implantable heart assist device from Frazier died within a year, nearly double the national mortality rate for such patients.” The St. Luke’s and Texas Heart executives, according to the exposé, “took little or no action to rein in a doctor whose work continues to earn the hospital international acclaim.” In June, Medicare announced it was cutting off all payments to the hospital’s heart transplant program.

Frazier claimed his surgical outcomes were worse because his patients were sicker and at higher risk than those treated at other hospitals. His supporters contend that his life has been one of service to such patients. They asserted to the Chronicle that “many in Houston and across the country…would not be alive if not for Frazier’s willingness to take the most difficult cases.” His vindication, some of these defenders claim, was the 2010 FDA approval of a “continuous-flow LVAD” for heart failure. “If he broke rules…it was to give dying people a shot at survival, a mission that consumed his life,” one said.

For nearly forty years, I’ve conducted clinical trials of experimental therapies—not devices, but drugs. These studies largely involved patients with advanced cancer or AIDS, desperate diseases for which, at times, desperate remedies were given. It was agonizing to tell some patients that they were judged too ill to receive the experimental treatment.

The temptation to break the trial’s rules, to imagine oneself as a heroic warrior and treat patients anyway, is a powerful one. The more I felt its pull, the more I came to appreciate that third-party oversight is essential when considering deviation from a protocol. A clinical investigator can appeal to the IRB and the drug maker for exemptions so as to include patients who do not fall within the inclusion criteria of the trial. Doctors can also petition the FDA for permission to treat one patient individually, entirely off protocol. We need such guardrails to protect patients not only from extreme risks from experimental therapies to the quality and longevity of their lives but also from distorted judgment resulting from a doctor’s mixed emotions of compassion and ambition.

Last year, the FDA, Health Canada, and the European Union all approved the SynCardia artificial heart. It requires the patient to be tethered at all times, writes McKellar, to a “clunky” external pneumatic apparatus with caretakers in attendance 24/7, hardly the device that Frazier and others envisioned that is self-contained and can be “implanted and then forgotten.” For those whose left ventricle lacks sufficient muscular force, thereby starving tissues of oxygen-rich blood, LVADs have been incrementally improved.

In April of this year, The New England Journal of Medicine published two-year outcomes comparing an LVAD that uses centrifugal flow with one that uses axial flow in heart failure patients. Although the former, which was championed by Frazier and his team, showed somewhat better performance with respect to pump malfunction and clotting, there was still the same risk of disabling stroke, gastrointestinal bleeding, and death. An accompanying editorial concluded that “even with this next-generation [centrifugal flow] device…complications occur at an unacceptably high frequency, and there remains a pressing need for additional improvements in…technology.”3 That pressing need must be tightly yoked to strict ethical standards in human experimentation.

This Issue

November 22, 2018

A Very Grim Forecast

Romanticism’s Unruly Hero

The Crash That Failed

-

1

“The Dracula of Medical Technology,” The New York Times, May 16, 1988. ↩

-

2

Mike Hixenbaugh (Houston Chronicle) and Charles Ornstein (ProPublica), “Heart Failure: A Houston Surgeon’s Hidden History of Research Violations, Conflicts of Interest and Poor Outcomes,” Houston Chronicle, May 24, 2018. See also Ornstein and Hixenbaugh, “Supporters of a Famed Houston Surgeon Have Alleged Inaccuracies in Our Investigation. Here’s Our Response,” Houston Chronicle, June 29, 2018. ↩

-

3

Mandeep R. Mehra, Daniel J. Goldstein, Nir Uriel, et al., “Two-Year Outcomes with a Magnetically Levitated Cardiac Pump in Heart Failure,” and Mark H. Drazner, “A New Left Ventricular Assist Device—Better, but Still Not Ideal,” The New England Journal of Medicine, Vol. 378, No. 15 (April 12, 2018). ↩