The tall building on Uprising Square

is a monument

to the luminary of all sciences.

But soar up in the lift,

enter Gnesin’s apartment—

and cults and monuments

slip out of your mind.

With this tall stone needle

Stalin may have scratched

the sky of socialism,

but the old composer’s apartment

makes you forget this.

“These spectacles,” I hear,

“were worn by Nikolay Andreyevich.”

(Gnesin is telling me about

his teacher, Nikolay Rimsky-Korsakov.)

“And this book,” adds Galina Mavrikiyevna,

“is a present from him.” A breath

of the past, of the sea, of the composers

we call

the Mighty Handful.

Gnesin sits down at the piano.

He sits there for a long time,

bowing his head

with its triangular beard.

He sits there so long

I wonder

if he has dozed off.

And Galina Mavrikiyevna

begs him not to play, not

to remember, not to upset

himself. But it’s impossible

not to remember. Not to remember

hurts. To remember

hurts still more. But then,

who really knows, who can say?

Gnesin looks pale and sad.

Not long before this, he had suffered

a stroke—soon after

an official meeting with Zhdanov.

Zhdanov had played the piano

to the assembled composers;

cruelty often likes to adopt

the dress of sentimentality—

a hatchet beside a curtain of light blue tulle.

Zhdanov had pounded away at the keys,

as if pounding his 1946 decree

into the composers’ skulls.

Prokofiev, Myaskovsky,

Shostakovich, Khachaturian, and others

had listened. Not one of them

said a thing:

What could they say?

Only Gnesin got to his feet

and, gently as ever,

said, “And you

dare

to teach us

about music?”

No answer. The silence

did not bode well.

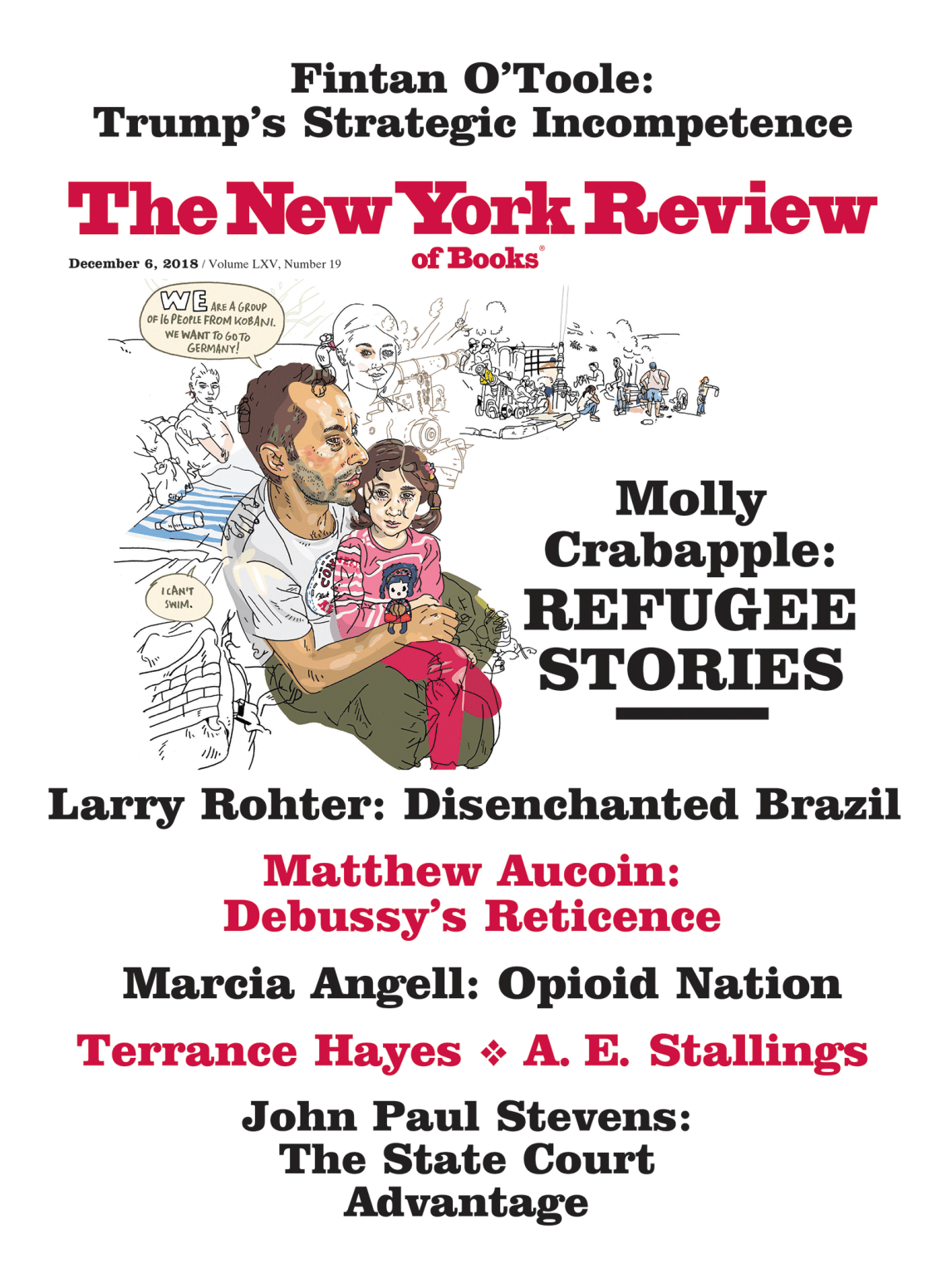

This Issue

December 6, 2018

Saboteur in Chief

That Formal Feeling

Opioid Nation