On my way to water the strawberries

at dusk—I gardened in those days—

I saw a raccoon clasping the outdoor spigot

like a sailor’s wheel, using both paws,

that seemed more and more like hands

as it kept twisting until water gushed

out of the copper nozzle and it drank.

I hadn’t thought of it in years, not even

after I saw another raccoon, high-stepping

the coyote fence midday with a limp vole

overhanging its mouth. Such a singular sight,

I had to tell you, and blurted it out as soon

as I saw you, a piece of domestic gossip

like the first crocus or noisy neighbors:

common property, like so much in marriage—

a small business, a friend called it, down to

the cooked books. Only later, after I recognized

the raccoon sauntering through a line

in one of your poems…only after the pressure

cooker of my displeasure caused you to recast

your raccoon and vole as skunk and mole,

did I flash on the one I’d seen decades before:

its lack of furtiveness, the air it had

of being within its rights, the way it took its time

to retrace its steps to turn the water off.

—Or did it amble on and let the water run?

No copyright protects idle talk, you might have said,

or, The imaginarium of marriage knows no bounds.

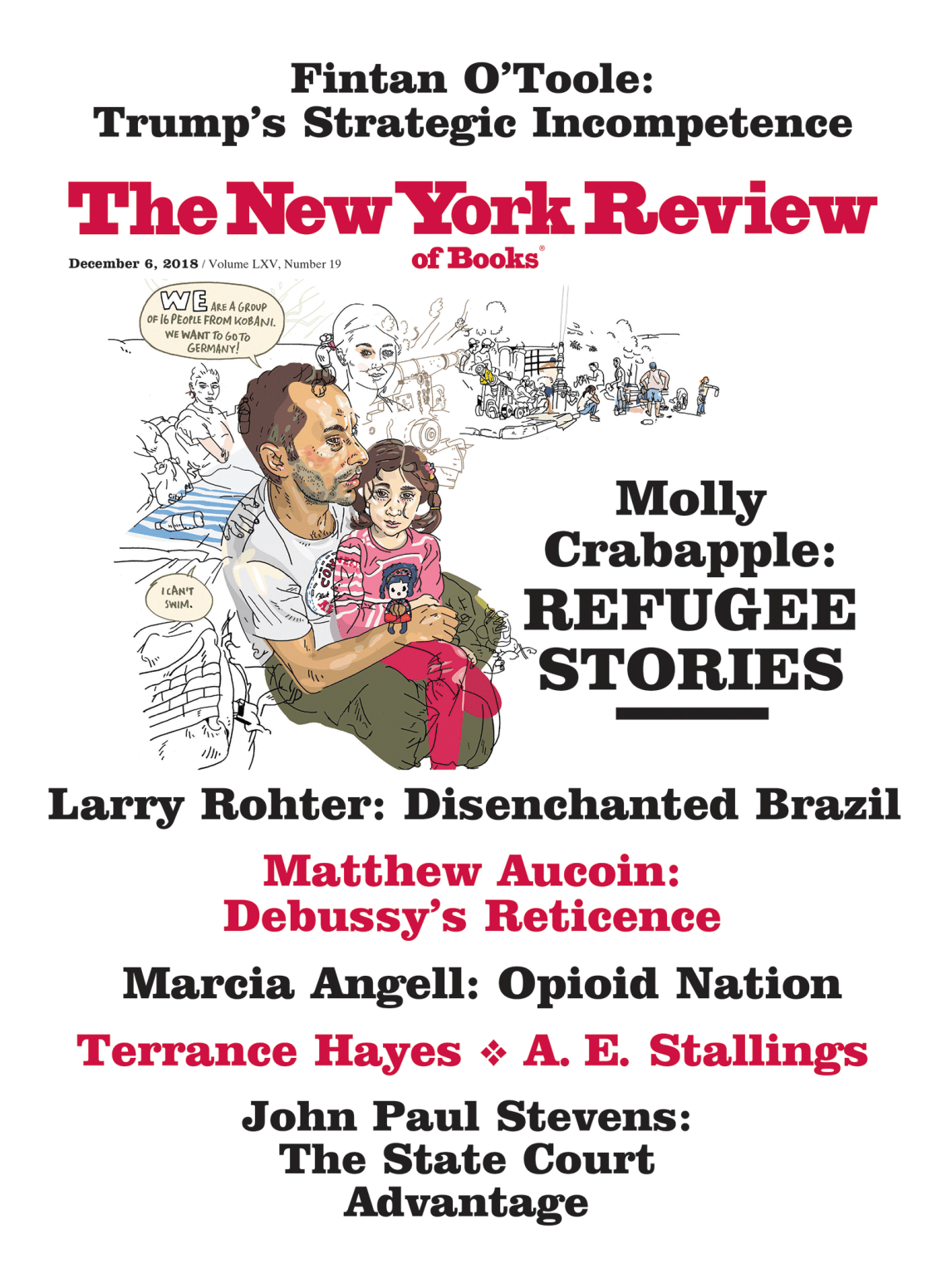

This Issue

December 6, 2018

Saboteur in Chief

That Formal Feeling

Opioid Nation