Michael Gervers

Mark the Evangelist; illustration from the Garima Gospels, late fifth or sixth century CE. As Peter Brown writes, the discovery of the gospels at the Ethiopian monastery of Abba Garima confirms G.W. Bowersock’s emphasis in The Crucible of Islam on the importance of the kingdom of Axum, to which early Muslims fled for protection in about 615.

To write about the Arabian background of the Prophet Muhammad, about the origin of Islam in Mecca and Medina, and about the first conquests that led to the formation of the Arab empire (roughly between 560 and 690 AD) is to attempt to describe the first moments of a supernova—the flash of a stupendous detonation that marks the death of a massive star and the release of enormous amounts of energy. G.W. Bowersock has met this challenge in a little book of explosive originality and penetrating judgment.

In his scholarly trajectory, Bowersock has often paced himself against Edward Gibbon. He has now thoroughly outpaced him. His first books, Augustus and the Greek World (1965) and Greek Sophists in the Roman Empire (1969), took us into the age of the Antonines in the second century AD, with which Gibbon began his majestic account of the decline of the Roman Empire. But a vivid spirit of curiosity and a zest for truth, worthy of his mentor the British historian Ronald Syme, have driven him ever further forward in time and ever further east. He has now reached the Arabia of the Prophet Muhammad and the first tentative generations of Islamic rule in the Middle East.

The Crucible of Islam is the last of a trilogy. The Throne of Adulis: Red Sea Wars on the Eve of Islam (2013) described the sixth-century confrontation between the Christian kingdom of Ethiopia and the Jewish kings of Himyar for control of southern Arabia. Empires in Collision in Late Antiquity (2012) conjured up the epoch-making struggle of the Persian and Eastern Roman empires for the control of the Middle East at the beginning of the seventh century, and the repercussions of this clash of giants on the Arabian peninsula where the Prophet Muhammad had already begun to preach.1 With The Crucible of Islam we reach the very center of this roiling world. We look into the depths of the crucible itself, to seize, in a true historical perspective, the “molten ingredients” that came to form Islam.

Bowersock urges us to take his title, The Crucible of Islam, seriously: “The formation of the vessel that Muhammad bequeathed to the world under the name of Islam took place in a crucible.” It is to the walls of this crucible and to the ingredients that were fed into it—to the environment of the Prophet and to the materials from which he created his message—that he directs our attention.

Bowersock evokes a series of landscapes: first, sixth-century Arabia, crisscrossed by a checkerboard pattern of conflict between Christians and Jews; then Ethiopia, the “sleeping giant” at the southern end of the Red Sea; after that, central Arabia, which was a veritable “Burned Over District” of monotheist prophets who were contemporaries and rivals of Muhammad. Lastly we turn to three cities: Mecca, Medina, and Jerusalem are examined in vivid close-up. His book ends in 691 AD, with the building of the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem. The Dome of the Rock is still with us. It is a reminder, in our times, that the headlong events of the late sixth and early seventh centuries really happened, and that they have had consequences up to this day. All the more reason for us to strive to get the story right.

Here Bowersock does not let us down. His book is an exercise in the art of historical truth. Bowersock is a classical scholar. He derives his skills from a tradition that reaches back to the Renaissance, to Erasmus and to Lorenzo Valla, whose demolition of the legendary Donation of Constantine he has himself translated with gusto.2 His book derives its strength from the method advocated by the great classical scholar Richard Bentley (1662–1742): ratio et res ipsa—reason confronting the thing itself.

No more severe test of this method can be thought of than the study of the origins of Islam. For to look into the white-hot center of our crucible—the preaching of the Koran and the early days of Islam—is to face a “disquieting emptiness.” The sheer intensity of the Koran makes it difficult to provide it with a setting. Our knowledge of the early days of the Muslim community depends largely on traditions that were assembled to make a continuous history almost two centuries after the event. In recent times, a tide of skepticism has washed over these late texts. Bowersock calls a halt to this hyperskepticism:

Rigid methodologies have run their course by now. A classical scholar and ancient historian, such as the present writer, may perhaps be permitted to say that the factional quarrels that have bedeviled Western scholarship on early Islam should be brought to a close…. Minimalism is not the way to throw light on a dark age.

Knowledge of the biases of later Muslim historians when they wrote about the first century of Islam “does not altogether indict them as unworthy of attention. It simply reminds the historian to be constantly alert.” Part of the joy of reading this account of the background and emergence of early Islam is the knowledge that Bowersock has built it from solid stones, the weight of every one of which he has tested with his own critical mind. Secure that we are in the hands of a master, let us think about the implications of the substantial gains to scholarship that Bowersock has brought us in this compressed masterpiece.

Advertisement

Firstly, he has done justice to the history of the Arabian peninsula as a whole in the century before Islam. He has shown that Arabia was no remote blank on the map of the classical world. It was a region swept with bitter conflicts that took religious form, pitting Jews against Christians. War in the name of religion was not an innovation brought to the Middle East by Islam. It had been a constant feature of sixth-century Arabia. Eastern Rome and Persia had reached into the heart of the peninsula by fostering religious antagonisms. Christians had looked to Eastern Rome with its base in Constantinople. Jews and polytheists had looked to Persia—with its Zoroastrian regime that was more open to religious diversity among its subjects than was the stridently Christian government of Eastern Rome.

This situation had come about because of the nature of power in the Arabian world. The leaders of the ambitious kingdoms that emerged in the region in the course of the fifth and sixth centuries did not think of themselves as ruling bounded entities, like modern states. They thought in more intensely personalized terms. Each ruler saw himself as placed at the top of a pyramid of loyalty whose extent each strove to increase by all possible means. Each was committed to ideological overkill, to staking out wild claims to dominance of areas far larger than they could control. It was respect that each ruler craved—bluntly, recognition that he was Numero Uno in his region—quite as much as direct rule over territory.

Those who stood at the head of these fragile pyramids of respect reached out for further validation to Eastern Rome and Persia. Like the chieftains of Native American nations of the eighteenth century, who sought prestige through contact with Onontio—their “Great Father,” the French governor at Quebec, and, beyond him, Louis XV in Paris—these competitive leaders valued their contact with distant and glorious kings. One sheikh, for instance, returned from the Persian court with a bright green silken robe. His envious peers called him “little green cabbage.” But it had been worth it. He had brought back a speck of glory from distant Persia. It was along lines of communication opened up by a restless search for prestige and recognition that less innocent tokens of respect—ideological messages heavy with possibilities for conflict between religious groups—made their way from the capitals of the two great empires of the Middle East into the very heart of Arabia.

This situation did not change with the arrival of Islam. Bowersock has espoused with generous acknowledgment the suggestion of Michael Lecker that the migration of the followers of Muhammad from Mecca to Medina in 622—the famous hijra, from which all Muslims date the history of their faith—may have had an Eastern Roman dimension.3 He suggests that the emperor Heraclius (reigned from 610 to 641) may have planned, through his Arab intermediaries, to induce Muhammad and his followers to settle in Medina. Heraclius might have seen Muhammad and his companions as a pro-Christian, pro–Eastern Roman religious group; and he might have hoped that they would hold in check the pro-Persian Jewish tribes who had formerly dominated the oasis.

Secondly, in addition to laying out a history of Arabia, Bowersock makes very clear that what was happening with kings was happening also with gods. In Arabia, gods were gods: “Idols were still both numerous and numinous.” They were not mere “angels”—anodyne emanations of a single high god, as many students of religion would want us to believe. Arabia was not on its way toward a diluted monotheism. Rather, it was as divided in religious matters as it was in its politics.

Despite the support of major kingdoms, Christianity and Judaism did not cover all the peninsula. Entire tribes and rich oasis cities (of which Mecca was only one among others) prided themselves on the multiplicity of their deities. Some gods were bigger than others. Like human rulers, gods arranged themselves in pyramids of loyalty. Some gods and goddesses were worshiped as intercessors with greater gods. But to deny their existence, to dismiss the gods as mere imaginative clutter, was a deeply disturbing proposition. To do so was to replace a carefully balanced hierarchy of invisible powers (similar to the pyramids of loyalty that maintained the glory of human kings) with a single being who held a naked monopoly of power over all peoples and all lands.

Yet this was what “monotheist prophets” were saying. In al-Yamâma, in central Arabia, a prophet called Musaylima emerged at the same time as Muhammad. He also claimed to have received revelations. He was no mere copycat. He was a serious competitor to Muhammad in a common war against the gods. By bringing the two prophets together—Musaylima in central Arabia and Muhammad in the Hijaz, the region in the west of the peninsula—Bowersock enables us to take the full measure of the religious crisis that swept Arabia in the early seventh century.

Thirdly, Bowersock allows us to appreciate the richness and complexity of the world that adjoined Arabia in the time of Muhammad. His chapter on the flight of early Muslims to Axum, in present-day northern Ethiopia, to seek protection from the negus (ruler) of Ethiopia in around 615, brings us to a Christian kingdom at the foot of the Red Sea.

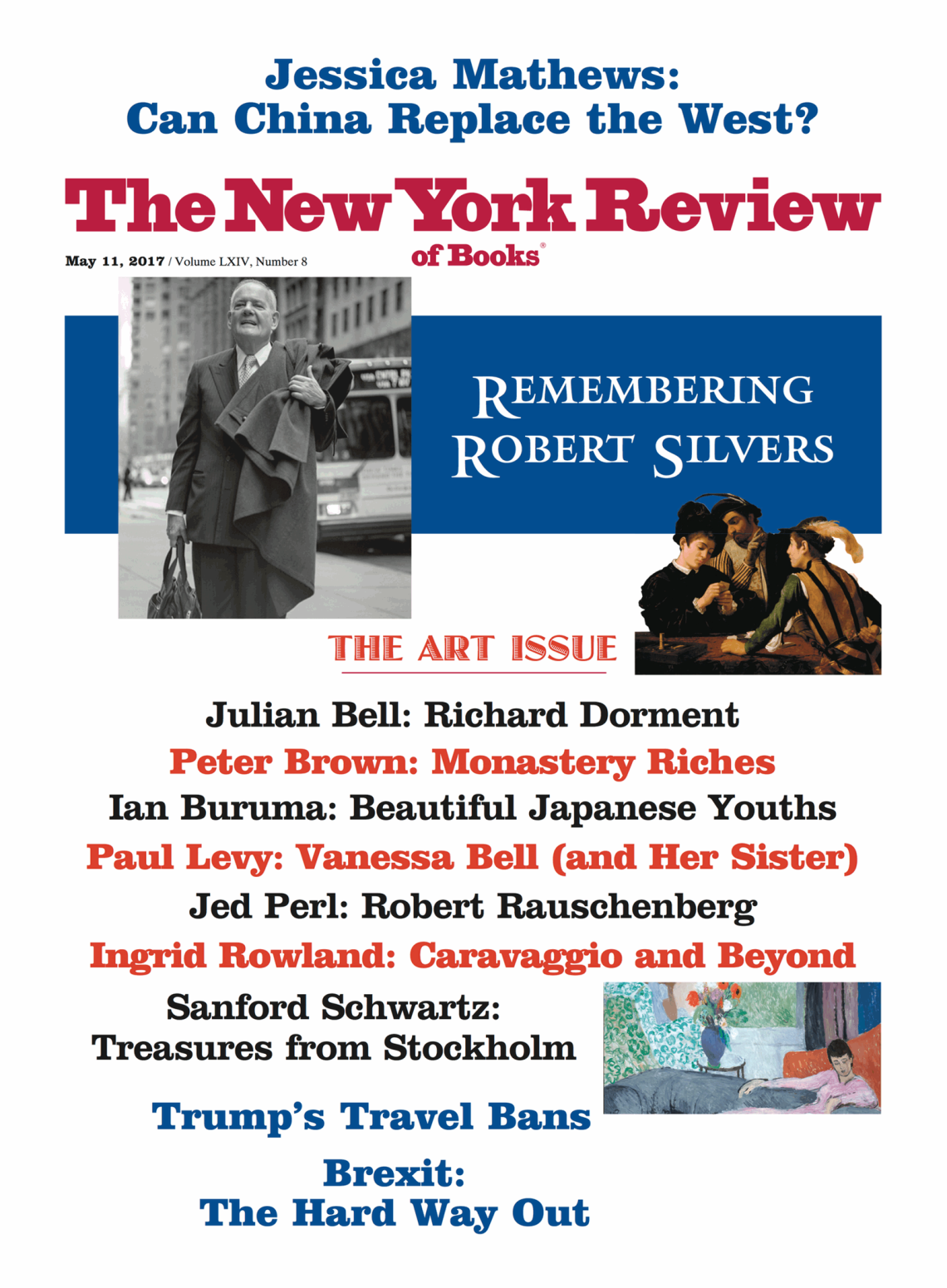

A new discovery confirms Bowersock’s emphasis on the importance of Axum. This is a spectacular gospel book, now named the Garima Gospels from the monastery of Abba Garima (near Axum) where they had been preserved. These gospels had been overlooked by scholars, who took them for medieval copies. Carbon-14 analysis seems to suggest that they belong to the late fifth or sixth century.

The gospels contain portraits of evangelists and bishops, standing and facing us in contemporary clerical vestments, with great beards and piercing eyes. Only the evangelist Mark sits in profile in the white robe of a classical author, on a chair decorated with the spots of a leopard skin—once the sign of high rank in Pharaonic Egypt. The writing table in front of him has been turned, with a proto-baroque touch, into a merry dolphin balancing on its nose (see illustration on page 48).

We are looking at a specimen of late classical art at its most hauntingly exuberant. Along with the portraits of holy figures, a set of written tables of the canon grip the eye. These tables had been drawn up to enable the reader to find parallel passages in all of the four gospels. They harmonized the different accounts, in the different gospels, of the life and sayings of Jesus. They quickly became objects of reverent awe in their own right: they declared the mystical harmony of the gospels, now gathered into one stunningly magnificent volume. In the Garima Gospels, each canon table stands in a doorway of sumptuous majesty. The written text is framed by painted representations of columns in multicolored precious marbles, luxurious, drawn-back curtains, clamshell roofs of azure blue, and, above each arch (like a glimpse of Paradise), gardens filled with rare birds.

Judith McKenzie (with her colleagues) takes the reader through this scholarly feast with a sure touch and with justified enthusiasm. Here is the evidence for a spread of late classical art with deep roots in the great Hellenistic cities of the East—most notably Alexandria—for whose existence she has long been a passionate advocate.

But the main excitement of this discovery is that the great gospel book may well have been produced in Ethiopia itself. Among the many birds perched above the archways of the canon tables we can see the crowned eagle—a bird of Ethiopia, never seen further north. That this gem of late classical art was produced in Axum is a measure of the extent to which, in the Middle East, the cultural centers of the worldwide Christian Church had shifted to the south, away from Europe and the Mediterranean. It is this silent subsidence that would soon be rendered irreversible by the conquests of Islam. The Companions of the Prophet did right to visit Axum in 615.

Another monument, recently saved from oblivion, is as exciting as the Garima Gospels. In a splendidly produced volume, Elizabeth Bolman presents the results of the restoration work carried out by the American Research Center in Egypt at the Red Monastery, near Sohag, in Upper Egypt. What had once been a sad ruin, its decoration hidden beneath thick layers of soot, has been renovated. Above all, the great triple apse (the triconch) of the sanctuary of the monastic church has been meticulously cleaned and restored (see illustration on page 49).

The result, in Bolman’s justifiably proud words, is a “staggering spectacle.” Here we are not confronted with the chaste apses that we usually associate with monastic buildings. Instead, the three adjacent apses, which make up the triconch, are like the backdrop of a great baroque fountain or the flamboyant stage set of a late classical theater. Two rows of columns set into the curve of the apses rise above each other, divided by massive entablatures—ledges of richly painted stone. Solid, decorated niches, framing the faces of holy persons, burst out of the walls. The space of the triconch, in which the sanctuary of the church would have stood, comes alive. It is “crowded, muscular and three-dimensional.”

Above all, the entire surface is covered from top to bottom with intricate decoration in encaustic paint. Encaustic paint has none of the chastity of fresco. It consists of colored molten wax, laid on by painters who would have carried little braziers to keep fluid the pans of molten wax to which vivid pigments had been added. Buffed to produce a satin-like sheen, the painted surfaces of the monastery’s church would have shone like precious marble and mosaic.

The exuberant decoration of the great church of the Red Monastery is likely to have been an exact contemporary of the Garima Gospels. Far from being peripheral to the Christian world, artists in the kingdom of Axum and in the Coptic monasteries of Upper Egypt still shared a late classical idiom that stretched, like a great carpet of many vivid hues, down the Nile toward the edge of Africa.

This stunning monument leaves little room for the dismissive manner with which the Coptic Church in Egypt has been treated by so many Western scholars. This was no burned-out Christianity, cut off from the main stream of culture. In the well-chosen words of Elizabeth Bolman, a monument like the Red Monastery

must surely banish once and for all the remarkably persistent and profound error of characterizing Egyptian monks…as unlettered and ignorant and classifying their cultural production as substandard.

These two books make plain that when the Arab armies swept across Syria and Egypt in the 630s and 640s they did not encounter demoralized and culturally stagnant populations. What, then, did they meet? Let us return to The Crucible of Islam. In the final chapters, Bowersock retells the story of the Arab invasions with a challenging freshness. It is not the old story as we have heard it: no previous decay of Eastern Roman society; no barbarous onslaught from the desert; no instant triumph of Islam over the Christians.

Instead of offering this conventional account, Bowersock enters into the minds of contemporaries to recapture their fears and hatreds. Their mental horizons were filled with the prospect of dangers and enemies different from those that we, with hindsight, would expect. He introduces us to a generation overshadowed by the memory of the Persian invasions of the 610s and 620s. Persians, not Arabs, were their traditional enemies. As Zoroastrians, the Persians were regarded as pagans. For this reason, their success had been particularly demoralizing to the subjects of a Christian empire. Nowhere had this been more true than in Jerusalem, the religious center of the Christian world.

In 614, the Persians fell on the city. They took Jerusalem by storm. They carried the relic of the Holy Cross from the church of the Holy Sepulcher of Christ back with them to Persia. Apparently, the Persians had also befriended the local Jewish population. This is not surprising. It had happened frequently in Arabia. The Persian Empire stood for tolerance. The Zoroastrian government was more tolerant of religious minorities of all kinds, and especially of the Jews, than was the Christian Eastern Roman Empire. The Persians brought with them a tantalizing breath of freedom.

Whatever really happened in Jerusalem in 614, its capture was “a shattering jolt” to the Christian myth of the inviolability of the Holy Places and to the Christian claim of enjoying a monopoly on the holy city. Inevitably, when the emperor Heraclius brought back the Holy Cross in triumph to Jerusalem in 629, it was a time for revenge. Heraclius allegedly forbade any Jew to live within a three-mile radius of the city.

Hence the peculiar atmosphere of the first years of the Arab invasions that began in 633. The Arab armies did not fall on a devastated landscape. Bowersock is emphatic on this point: “When the armies of Muhammad eventually arrived, they did not find a shattered civilization and a ruined economy.” But the leaders of these armies were met by figures who had inherited the antipathies of a previous, bitter war. Jews and Persians were still uppermost in their minds—not Arabs and Muslims. They were anxious to strike a deal with these newcomers that preserved the prosperity of the region and that guaranteed their own place in it. They took care that if Jerusalem had to be surrendered to the Arabs, there would, at least, be no repetition of what had happened in 614. There would be no sudden inversion of the Christian order.

In 638, the Patriarch Sophronius welcomed the Muslims. He went out to greet the Caliph Umar, “in one of the most remarkable and indicative episodes in early Islamic history.” Umar entered the city without a struggle. Sophronius got what he wanted. Umar decreed that no Jew was to live in Jerusalem. As far as the patriarch was concerned, Christian hegemony had been validated—not overturned—by the Arab conquest. Similar deals were struck throughout the eastern provinces, always to the advantage of the Christian populations. For the Christians, memories of the Persians and hatred of the Jews trumped their own ecclesiastical divisions; and the prospect of a return to business as usual in a comfortable Middle East trumped any reserves about the new religion of the Arabs.

Nonetheless, it was a fateful agreement. A new Arab kingdom had indeed brought a new religion. In 691, the caliph Abd al-Malik built the Dome of the Rock. The mosaics of the interior carried inscriptions that echoed the words of the Koran. They summed up the points of disagreement between Muslims and Christians. God was One. He was not Three. Jesus Christ had been a servant of God, not a Son of God. Any other view of Christ was proclaiming an unwarranted exaggeration. “Do not go beyond the bounds of your religion…. Stop, it is better for you.”

But the warning was delivered in Arabic, on the inner walls of a Muslim holy place. Nothing in the calligraphed texts suggests that Abd al-Malik had any interest in converting the Christians. More significantly, only Christians were addressed in these inscriptions. In Jerusalem, at least, the Jews were out of the picture: “The embers of the fires that burned in Jerusalem in 614 were still glowing.” In this way, ancient enmities, which had already polarized the Arabian peninsula in the sixth century, still determined the decisions of those who witnessed the birth of a new world empire in the seventh.

The last pages of Bowersock’s book are austere and sobering. The more Muslims, Jews, and Christians entered into dialogue with one another, the more each religion came to recognize areas of incompatibility with the others. Bowersock cites the famous letter that Maimonides wrote to the Jews of Yemen in 1172. Jews and Christians shared the same holy scriptures, but they did not share the same view of God. The Christian notion of the Trinity “was a dissonant component in this conjunction of monotheisms.” And while Jews and Muslims shared the same belief in an undivided God, they did not share the same holy scriptures.

Bowersock’s book shows, with unflinching scholarship, how these incompatibilities—many of them long-standing—had been thrown together in the age of Muhammad and his successors in the crucible of Islam. They are perilous incompatibilities. How each generation handles them is a test of its humanity. In recent times, alas, few generations have passed this test. But we have to keep on trying. To get the beginning of the story right is part of this effort. For this reason, we must be grateful to Bowersock for giving us, at this time, a masterpiece of the historian’s craft.

-

1

See my review of both books in these pages, July 11, 2013. ↩

-

2

Lorenzo Valla, On the Donation of Constantine, translated by G.W. Bowersock (I Tatti Renaissance Library/Harvard University Press, 2007). ↩

-

3

Michael Lecker, “The Goal of the Khazraj in the Battle of Bu’âth,” in Les Jafnides: des rois arabes au service de Byzance, edited by Denis Guenequand and Christian Julien Robin (Paris: de Boccard, 2015), pp. 278–279. ↩