Eric Karpeles, a painter and an impassioned reader of Proust—he is the author of Paintings in Proust: A Visual Companion to In Search of Lost Time (2008)—had never even heard of Józef Czapski until a friend sent him a slim volume in French, Proust contre la déchéance, which he has now translated under the title Lost Time. It consists of five lectures on Proust that Czapski delivered in 1940–1941, during his captivity in a Soviet prison camp. Karpeles read it in a single sitting and became obsessed with its author.

Who was this man capable of bringing Proust to life, in those appalling conditions, without a book to refer to, for an audience of some forty Polish officers suffering from utmost deprivation? Capable of setting forth the literary background of Proust’s masterpiece, summing up its overarching themes, and even quoting lengthy passages almost word for word from memory to illustrate a fascinating convergence of Proust, Tolstoy, and Dostoevsky? Driven by curiosity, Karpeles discovered other texts by Czapski and some contemporaneous accounts of him. Frustrated by their inadequacy, he set out to do his own research. It took him more than five years to write Almost Nothing: The 20th-Century Art and Life of Józef Czapski, a remarkably vivid portrait, notable for the clarity with which it places a life unusual for its breadth and complexity in its larger historical setting.

Czapski’s tormented life, ravaged by wars and revolutions, traversed nearly the entire twentieth century. He was born in Prague in 1896, into one of those European aristocratic families whose branches are so intertwined that it is impossible to assign them a specific nationality. A Polish father, an Austrian mother, and Russian, Baltic, Czech, and German cousins were his closest relatives. He spent his childhood with his brother and five sisters on the family estate of Przyłuki in Belarus, then part of the Russian Empire, until he was sent at around the age of thirteen to continue his studies in Saint Petersburg. In January 1917, he enrolled in Tsar Nicholas II’s Corps des Pages, an academy that trained sons of the nobility and senior officials. A month later the February Revolution broke out, and his life henceforth followed a vertiginous course that ended in 1993, when he died in France at the age of ninety-six.

In May 1918, just months before the end of World War I, Czapski was in Warsaw. Poland, which had been partitioned for more than a century among the Austro-Hungarian, Prussian, and Russian empires, emerged from the war an independent state, but beginning in February 1919 tensions with Russia degenerated into a brutal conflict. Instead of studying to be a painter, as he had wished to do, Czapski volunteered immediately for military service. His courage in combat earned him the Polish Order of the Virtuti Militari, the country’s highest military decoration, which he received at the same time as a French officer, Charles de Gaulle, who had been sent to Poland as an observer and with whom he had become friends. Poland defeated Russia in 1921, but its independence would last barely twenty years.

Demobilized and determined to devote his life to painting, Czapski enrolled at the Kraków Academy of Fine Arts. As he later wrote, “I entered the world of my new friends, an intellectual atmosphere marked by a carefree assurance, a winning optimism, and a sensual joie de vivre totally alien to me.” He adapted so quickly that in 1923 he established the Paris Committee with a group of friends who were determined to explore Paris, its museums, and its galleries. The following year, they set off for a stay that was supposed to last six weeks but stretched out to seven years.

The support of Misia Sert, a society figure of Polish descent whom Czapski contacted through mutual friends, was crucial. She knew everyone in the arts in Paris and was infected by the enthusiasm of these young artists who lived from hand to mouth. When Czapski first turned to her for help, Karpeles writes, “she said, ‘Very well, come here tomorrow, we’ll take Picasso to lunch.’ The next day they all went to the Meurice. It was decided a fund-raising event was in order and after lunch Picasso agreed to be its patron.” For Czapski, those seven years were marked by his discovery of Bonnard’s Paradis harmonieux and Matisse’s explosion of color, the excitement of his own first shows, which gained him the encouragement of Dufy, Vuillard, Rouault, and even Bonnard himself, as well as his first sales of paintings (including one to Gertrude Stein).

Advertisement

It was at this time that Proust’s last volumes were published posthumously. From then on, Czapski never stopped reading and rereading Proust, and he published an enthusiastic essay about him in a Polish magazine. “Proust’s style gives the impression of a perpetual grazing and brushing; his touch, as flexible and fluttering as a flickering flame, is able to explore everything without breaking or twisting a thing,” he wrote. Another essential discovery was Goya, during a trip to Spain. “The shock of my life,” as he put it, came when he realized that the same artist could paint both classical portraits, with a perfect control of detail, and wild scenes of war and madness. This possibility of not having to choose between two styles came as a revelation:

Speaking of myself, I was long tormented by a duality of approach—analytical on the one hand, rational, growing from the Dutch tradition and to a certain extent from the pointillists, and on the other hand, the mad, the unpredictable—the true leap into the abyss. In this I saw a lack of integrated personality, a kind of psychic dividedness that I tried to overcome artificially, without success. With time I noticed the same phenomenon in a painter whose stature was not only equal to that of Matisse but who was one of the very greatest—Goya.

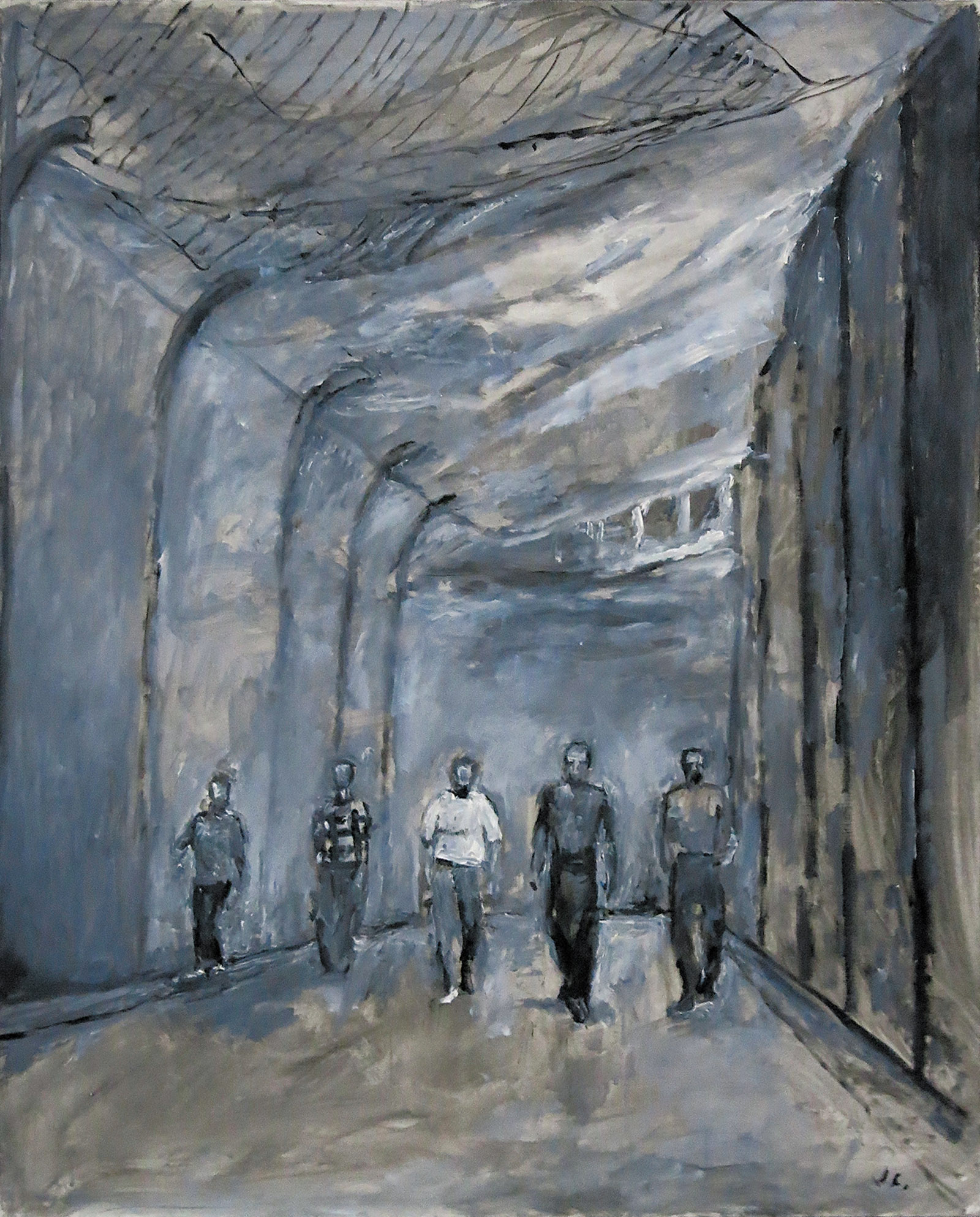

Upon his return to Warsaw in 1932, Czapski painted, wrote, and exhibited, notably in 1939 at the New York World’s Fair, but war broke out on September 1 of that year. Poland was attacked by both Germany and the USSR. Czapski was mobilized and on September 27 was taken prisoner by the Soviets, along with 15,000 other Polish officers. They were split up and sent to three camps: Starobielsk, in Ukraine (where Czapski ended up), Ostashkov, and Kozelsk. In the spring of 1940, Czapski and 394 of his comrades were transferred to Gryazovets, 250 miles north of Moscow. All the other prisoners were sent to an unknown location. He described his captivity in Memories of Starobielsk, a testament to his will to preserve some semblance of an intellectual life:

Intellectual effort, when conducted without books or notes, gives an entirely different sensation than when carried out under normal conditions. One’s involuntary memory acts much more forcefully, the memory of which Proust speaks and which he considered to be the sole source of literary creation. After a certain amount of time, things surface in our consciousness, details we hadn’t the slightest idea were even “stored” anywhere in our brain. What is more, those memories that come from our subconscious are more deeply rooted, more intimately bound up one with another, more personal.

That was the origin of Czapski’s lectures on Proust. Czapski also dictated the texts to two fellow prisoners and kept the transcripts, thanks to which this astonishing example of his spiritual strength and capacity to adapt to the worst conditions has been preserved.

A year later, on June 22, 1941, everything was upended. “To this day,” Czapski wrote, “I can still hear ringing in my ears the wild cry of exuberant enthusiasm thrown out by a scruffy colonel bending his whole upper body from the window: ‘Hitler attacked Russia!’” A new phase of the war began. Stalin agreed to free all the Polish prisoners and deportees in order to form an independent Polish army. General Władysław Anders learned in Lubyanka prison, where he had been tortured, that he had been chosen to command it.

Prisoners gathered from all corners of the Gulag, but the officers who were last seen in Starobielsk, Ostashkov, and Kozelsk never appeared. Czapski was assigned by Anders to investigate what had become of them, but he ran straight into a wall of silence. In the meantime, the Polish army, poorly fed, inadequately armed, and unable to train for combat, was evacuated to Iran in the spring of 1942, and then to Iraq. It was there, in April 1943, that news reached Czapski of the discovery by the German army of the Katyn massacre. As Karpeles writes, “The bodies of thousands of Polish officers had been found buried in their uniforms, their identity papers intact, stacked twelve deep.” There could be no doubt about it. These were the prisoners from the Kozelsk camp. The worst was now a certainty.

By way of Palestine and North Africa, the Poles rejoined the Allied front in Italy in May 1944 and helped capture the fortified abbey of Monte Cassino, southeast of Rome, after three earlier attacks had been thrown back. The Americans entered Rome on June 4, two days before the Normandy landings, while the Poles pushed north toward Ancona. Their singular situation was analyzed at the time by the American reporter Martha Gellhorn:

Advertisement

All the Poles talk about Russia all the time…. They follow the Russian advance across Poland with agonized interest. It seemed to me that up here, on the Polish sector of the Italian front, people knew either what was happening ten kilometers away or what was happening in Poland, and nothing else….

They fight an enemy in front of them and fight him superbly. And with their whole hearts they fear an ally, who is already in their homeland. For they do not believe that Russia will relinquish their country after the war; they fear they are to be sacrificed in this peace, as Czechoslovakia was in 1938.

Gellhorn’s article, commissioned by Collier’s, was never published. No one wanted to irritate “Uncle Joe,” the triumphant and indispensable ally. Czapski had few illusions, understanding clearly that for the Poles, still traumatized by the discovery of the Katyn massacre, the most important event of the summer of 1944 was the catastrophic Warsaw insurrection, while for the Allies the main news was the success of the Normandy invasion. His sense of unease was well justified: in February 1945, at the Yalta Conference, Stalin solidified his grip on Poland.

Czapski happened to be in Paris a few weeks before the German surrender on May 8, 1945. Going back to Poland under the new Communist regime was impossible. He was forty-nine years old, and he had to start his life over. For the next forty-eight years he lived in Maisons-Laffitte, on the outskirts of Paris, in a house that he shared with the rest of the staff of Kultura, the Polish-language political and literary magazine founded by Jerzy Giedroyc in June 1947.1 Despite its extremely meager funds, it enjoyed immense influence and high circulation, and Czapski would contribute to its pages for the rest of his life. But he was in a hurry to become a painter again.

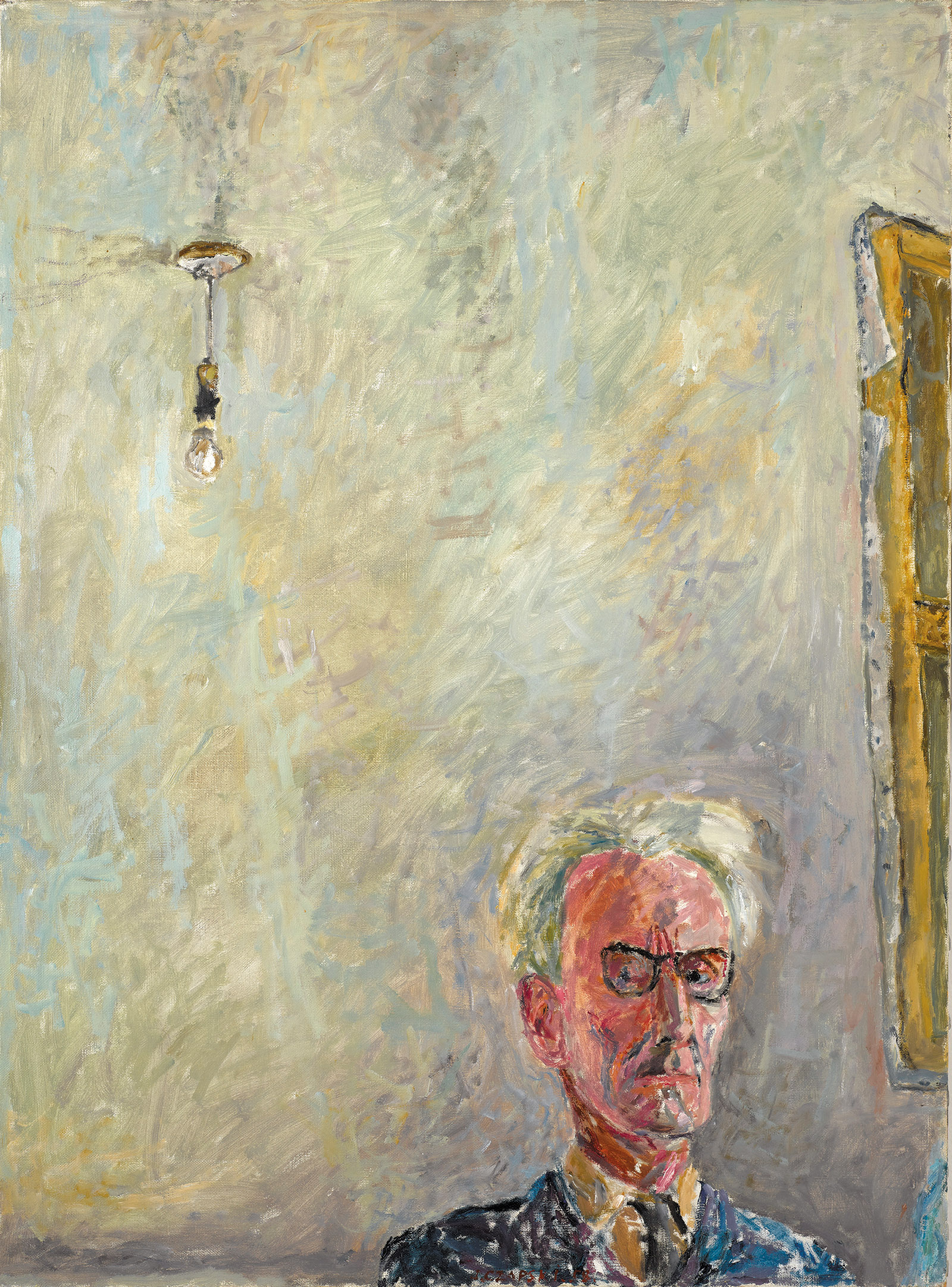

You can’t examine such a rich, varied, and turbulent life without identifying a guiding thread running through it. If Karpeles was attracted first of all by Czapski’s spiritual energy, he judged quite rightly that the unity of his life was to be found in his passion for painting. “My feverish application when painting,” noted Czapski in his diary, “may have been necessary over the years, it’s the only means I have of keeping from dissipation.”

He was never tempted to dabble in abstract art and remained unswervingly faithful to the precept of Turner (and secondarily of Elstir, the exemplary painter in Proust’s novel): paint what you see, not what you know. The result was often a powerful canvas that, in Czapski’s own words, could set one’s teeth on edge, with a subject that could as often as not be revolting. He noted that “a great many criticize me for bringing back from Marseille my Blind Man in front of the dirty green table of a café instead of a view of the Old Port. For painting the filthy steps of the Gare Saint Lazare in Paris.”

But his range as a painter was not narrow. His work is full of contrasts, equally rich in still lifes, landscapes, deeply felt portraits, and sketches, of which he made thousands. For many years, he exhibited regularly but sold little, until a Swiss collector offered to act as his dealer. Success followed immediately. He was eighty years old. Money had never interested him because “he was made uncomfortable by the monetary assessment of any item of supreme value.” Karpeles writes that when a German gallery suggested a series of shows of his works, provided he increase his prices tenfold,

Czapski rejected the offer. He wanted nothing to do with it, not wanting to be trapped, he said,…selling “only to bankers and speculators.”…The artificial inflation of the value of a work of art was not a game he saw himself playing.

On the other hand, an invitation to exhibit at the 1985 Paris Biennale alongside painters who were half a century younger than him gave him great pleasure. That pleasure, however, didn’t last. He was horribly shocked both by the paintings exhibited and the general atmosphere of the event:

My work is hanging next to another painter, who is showing one huge painting of a man pissing (literally) on a corpse, and another, even bigger, of Menachem Begin sitting in Hitler’s lap and nursing at his breast. On the day of the opening, a live cow, painted red and green, was let loose to wander among the galleries.

Czapski was eighty-nine, and his ability to revolt against the trampling of his values, of everything he respected, of what he considered just, had not slackened over the years. His moral and intellectual vigor never abandoned him. It is this intensity that made him so engaging and that Karpeles highlights so admirably.

I had known him since I was a child. He was a friend “from forever and for ever,” as he liked to say to my father, a Polish diplomat. For my sisters and me, wujek Józio (Uncle Józef) was part of the family. In these pages, I find him again exactly as I remember him. Just over six feet six inches tall, he irresistibly called to mind a Giacometti sculpture. When he strode briskly into a room, he never lost time on small talk: he leapt straight into the heart of things as if simply resuming a discussion. The age of his interlocutor was of no importance to him.

He always maintained a striking openness and youthfulness of spirit. At ninety, he fell in love with the work of Milton Avery: “It seems to me that Avery has figured out how to square the circle. The bloody struggle between abstract and figurative painters that I’ve seen and lived through seems resolved by this American painter.” Set free by an artist who had achieved the synthesis he had long dreamed of, he went on to produce an impressive series of still lifes until his eyes finally failed him. Although he stopped painting, he nevertheless continued to keep his diary.2 A few days before his death, he scribbled in the awkward handwriting of a blind man, Bonnard, Matisse, Goya, Proust, and, in big capital letters across the pages, KATYN, KATYN, KATYN.

Inhuman Land is a memoir written between 1942 and 1947, focusing on the year between Czapski’s liberation from the prisoner-of-war camp and his arrival in Iran with Anders’s army, during which he traveled across the USSR on his mission to find some trace of the missing Polish officers. By virtue of his Belarusian childhood, his youth in Saint Petersburg, his experience of the early period of the revolution, his Russian friendships, and his perfect command of the language, he “perceive[d] the Russian world…in all its complex, extremely interwoven, highly specific reality. This is why all absolute judgments of it seem to [him] so false and even iniquitous.”

Czapski was not a man who wrote in a linear fashion, hobbled by mere chronology. Overwhelmed by memories from different periods, he offers his reader a narrative that is often meandering but that conveys a powerful image of Russia at war, the formidable government under Stalin, and the sufferings of the populace, while simultaneously giving space to the moments of simple, primitive happiness he enjoyed after regaining his freedom, in spite of growing anguish as his search appeared increasingly futile:

As soon as we enjoy slightly better conditions, even if they are far from the normal ones we were once used to, each day brings experiences and pleasures to blot out our bitter or painful memories. For every one of us at the time, not just being at liberty, not just the chance to commune with women after two years without seeing a single one, but a piece of cheese, some meat and potatoes, and a glass of vodka or a bottle of beer were great treats.

During his stays in Moscow, he was once again able to buy books. A frivolous one about Parisian life in 1890 amused him during the two nights he spent waiting for a train in a packed station:

The entire floor was littered with hundreds of people, in an extremely emaciated state…. On the floor lay the thin stumps of legs, miserable, puffy faces, and heaps of ragged human figures in padded jackets over their naked chests….

I had always found it impossible to understand how Leonardo and the other Renaissance artists could have been so creative in an era of cruel tortures, of destruction and plague that wiped out entire cities. But now here I was…eagerly reading light, fragrant novellas…which was not so much an escape from surrounding reality for me, but just a way of dulling it. I was also suffering from a hunger for books, any book; those who have never been deprived of reading matter for months on end can have no idea of what it is like.

To retain one’s sanity one must learn not necessarily to forget but at least to free oneself from the recollection of the horror of those experiences: “No man could live or smile if he were always reminiscing without ever erasing any of his memories.” Czapski was saved both by his tireless work and by his curiosity.

Certainly in those days a Russian might be afraid to talk to a foreigner, but the interminable journeys by train offered some possibilities for conversation:

Nowhere in Russia did I ever manage to topple the walls of silence as often as in the trains, where the clank and rattle, and the almost anonymous, casual nature of the encounters created a sense, maybe illusory, of less of a threat, less chance of being denounced.

He provides a lengthy account, for example, of the conversation that he had with a railroad worker who told him about the great wave of panic in October 1941, when the Germans were threatening Moscow. The man had experienced starvation and intolerable living conditions, and yet “he admitted to being extremely fond of reading. He talked with delight about Dickens’s Nicholas Nickleby,” and confessed that he had once read through the night a novel by Sir Walter Scott.

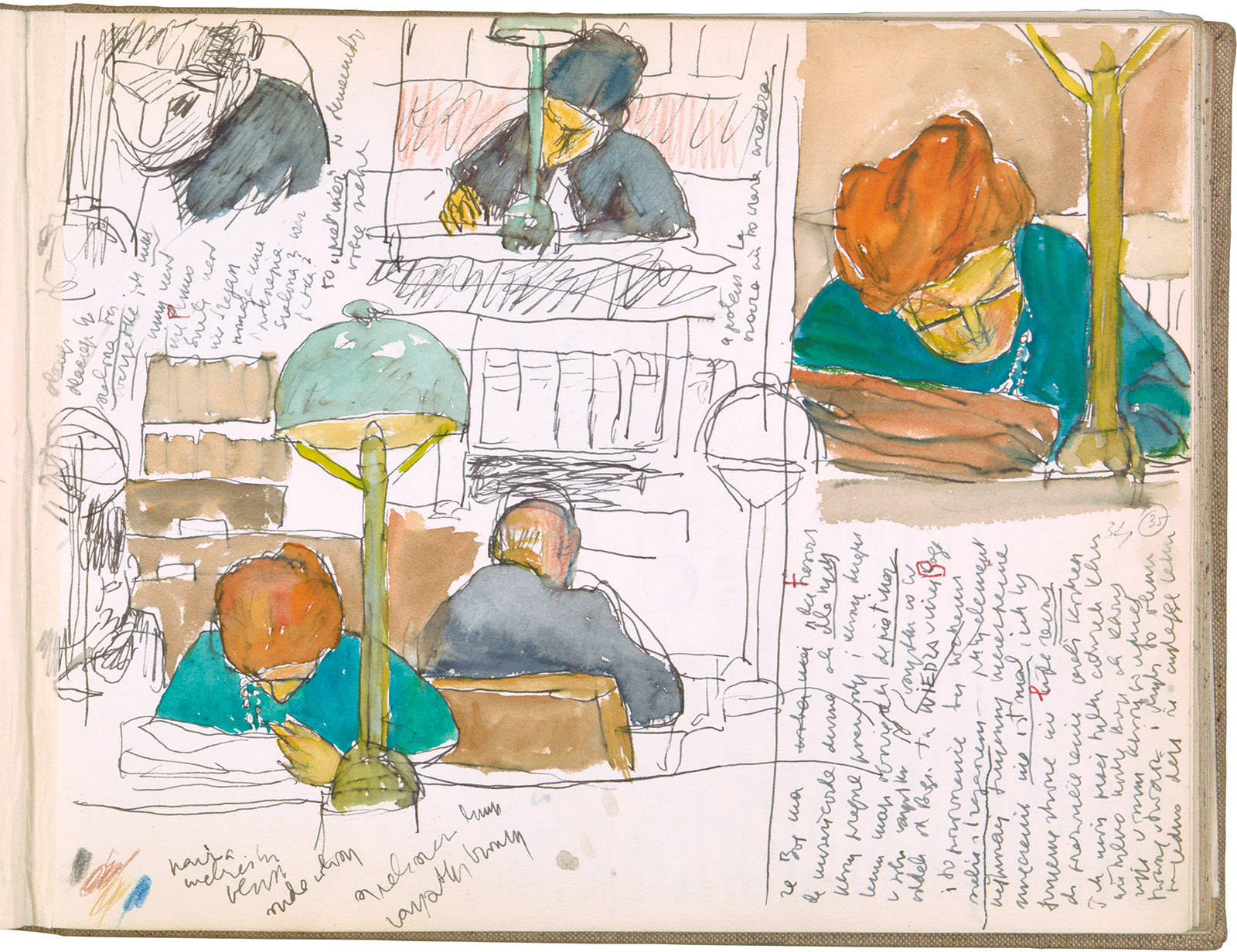

Czapski’s painter’s eye rescued him from despair. That is where we find the justification for Karpeles’s interpretation of his life. While he was in Russia, painting was of course out of the question, but he could sketch and, above all, jot down the things that struck him. Quite often in Czapski’s work, painting, drawing, and writing overlap. He writes like a painter. As he approached Tashkent, in Uzbekistan, he was first and foremost astounded by the art of irrigation as practiced by the inhabitants, and then the horizon captured his attention:

As soon as the gray sky cleared, it became strangely blue, acquiring a brighter color than I had ever seen before, vivid peacock-blue. Was it the contrast with the brown clay and the pink branches? Or was it really an unusual color, different from the sky in Poland, or in Italy, and totally different from the sky in Vologda and Gryazovets, where above the subtle green of the birch trees it was so pale blue as to look diluted, like watercolor?

Czapski’s account of his years in the USSR is stunning in its descriptions and its variations of vantage points. The cruelly constrained horizon of a prisoner of war opens out onto a vast country that he has the freedom to crisscross. There is a similar chronicle by the great Polish writer Gustaw Herling-Grudziński. Freed from the Gulag, he managed to travel thousands of miles to join Anders’s army. But all his energy was focused on the difficulties of overcoming the challenges along the way. Czapski’s point of view is much broader, as is the freedom with which he could move around and converse with Russians. Though his one conversation with Ilya Ehrenburg was a disappointment because of the poet’s cowardice—Ehrenburg spoke “in a loud voice, as if assuming…the room was bugged”—his meeting with Anna Akhmatova in Tashkent, during which she recited a poem to him about Petersburg/Leningrad, brought him unexpected joy. They met once again, in Paris in 1965, when he found her, as Karpeles writes, a “fragile emissary from an unburied past.”

After months of effort, he was forced to face facts: “I…still had no idea if my comrades were alive…. There were no more doors for me to knock on in Moscow in the hope of them being opened to me.” There was nothing for him to do but to follow the Polish army and leave the USSR. He went through one last checkpoint, passed through a gate surrounded by barbed wire, and entered Iran. “I automatically crossed myself and felt the driver’s hand giving my arm a friendly squeeze as he said: ‘Well, Captain, paradise is behind you now.’”

—Translated from the French by Antony Shugaar

This Issue

December 20, 2018

Damn It All

Prodigal Fathers

In the Valley of Fear

-

1

Founded in Rome by Giedroyc, with Józef Czapski, Zofia Hertz and her husband, Zygmunt, Gustaw Herling-Grudziński, and Juliusz Mieroszewski, Kultura was meant to be independent of the government-in-exile in London and refused to be anything more than the voice of the Poles who had fled communism. The magazine continued publishing until 2000 thanks to its tens of thousands of subscribers in twenty or so countries. Czapski played a crucial part not only by doing major fund-raising during his trips to Canada, the US, and South America, but also by forging relations between Kultura and the French literary world. His excellent relations with Albert Camus and Raymond Aron allowed him to arrange for the publication in France of many books and essays by Polish writers. The magazine, which claimed to be primarily political, was also highly regarded for its influence in the literary realm. There was a twofold clandestine movement swirling around Kultura. Polish sailors agreed to smuggle texts into Poland, and certain Polish writers and politicians brought texts to France to be published under pseudonyms. What’s more, Kultura offered émigré authors, scattered around the world, their only opportunity to publish in the Polish language.

In 1953 the Bibliothèque de Kultura series began. Its earliest publications were Witold Gombrowicz’s great work Trans-Atlantyk and Czesław Miłosz’s Zniewolony umysł (The Captive Mind), as well as a Polish translation of Orwell’s 1984. And thus the two greatest contemporary Polish authors—Miłosz, who received the Nobel Prize in 1980, and Gombrowicz, who was short-listed for the Nobel but lost by one vote in 1968—were published in Kultura. ↩ -

2

He never lost the habit he had begun in adolescence of keeping a diary, which he did practically until the day he died, mixing thoughts, jotted notes, quotations, and sketches. A total of 274 notebooks are held in the Princes Czartoryski Library in Kraków. ↩