The Silence of the Girls, Pat Barker’s unsentimental and beautiful new novel, tells the story of the Iliad as experienced by women captives, from inside the Greek camp overlooking the walls of the besieged city of Troy. They are the Greek heroes’ prizes, taken from conquered outlying towns and villages to be prostitutes, domestic workers, and, on occasion, wives. Herodotus, in his Histories, tells of the Ionian Greek customs with regard to their captured women: they

married Carian girls, whose parents they had killed. The fact that these women were forced into marriage after the murder of their fathers, husbands, and sons was the origin of the law, established by oath and passed down to their female descendants, forbidding them to sit at table with their husbands or to address them by name.

The novel is told, mostly in the first person, by Briseis, the captive queen awarded to Achilles, the Greeks’ greatest warrior. She becomes the motive for the quarrel between Achilles and Agamemnon, the commander of the Greek troops, and the resulting destruction their troops suffer, caused by the two men’s personal feud.

Homer’s epic opens as Agamemnon, who had his daughter Iphigenia sacrificed as an offering for good sailing conditions to Troy, encounters another kind of father in the Greek camp, a priest of Apollo, who has taken an unprecedented risk and come to the enemy camp to ask for his beloved daughter, Chryseis, to be released from Agamemnon’s household. Agamemnon refuses. In the coarsest speech of the epic, he insults the priest and gratuitously, pornographically, forces on the father a haunting vision of his daughter’s future as the king’s sex slave and household drone. She will never again be free or safe, since Agamemnon’s impulses are sovereign; she is his to beat or to kill, if he wants. The priest beseeches Apollo to punish the Greeks, and the god responds, sending a devastating plague.

Achilles calls an assembly to find its cause. Under his protection, the divining priest Calchas reveals that the plague is of divine origin, and that Agamemnon’s prize, Chryseis, must be restored to her father in order to appease Apollo. Though Agamemnon is furious with the priest’s assessment (and insults him in the style of Trump’s attack on the CNN reporter Jim Acosta—“Prophet of evil, never yet have you spoken anything good for me”), he has no choice but to assent. However, while Achilles is the Greek’s greatest warrior, Agamemnon is his superior in rank. The command structure is an iron hierarchy, and to restore his prestige, Agamemnon demands Achilles’s own prize, Briseis, as a substitute, humiliating his most valuable war champion. Briseis is taken from Achilles’s tent and led to Agamemnon’s. Achilles then refuses to use his extraordinary martial powers to fight for the Greeks, allowing them to be slaughtered and brought to the brink of destruction over the two men’s struggle for prestige.

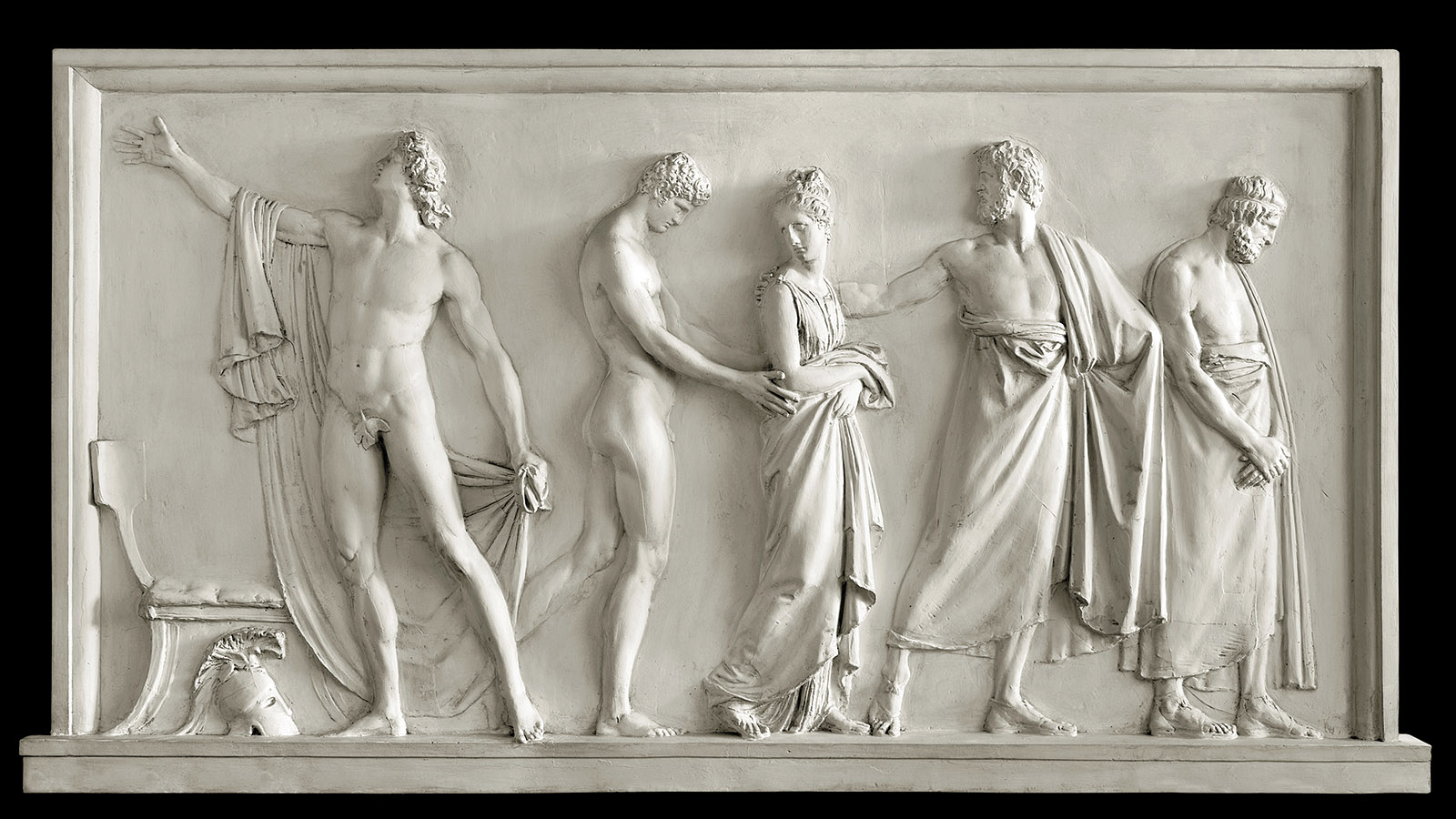

This is the scene painted circa 480 BC by an artist known as the Briseis painter on a red-figured kylix, or round two-handled wine cup, exhibited at the British Museum: on one side, Briseis, wearing a gracefully draped chiton and veil, is led by a bearded herald to Agamemnon’s tent. On the other side, Briseis, in the same elegant drapery, is led back to Achilles’s tent. If you look only at the painted figures, you will see nothing but beauty, order, and the timeless rhythms of ceremony—but the vessel is a brilliantly designed image of perpetual captivity. It is a cup with a double life, one story concealed inside the decorations of another, like the design of Pat Barker’s novel.

Barker’s work is inextricably associated with her examinations of the experience of war. She is most famous for her great World War I Regeneration trilogy, a study, among much else, of how states create men as warriors, but her Union Street trilogy, about the lives of working-class women, might also be described as war novels, focused on class warfare and the characters’ endurance of the pervasive violence integral to poverty.

The Silence of the Girls, like the German writer Christa Wolf’s 1984 novel Cassandra, is a fiction that acts as what we might think of as a séance in reverse: these novels do not use the living to summon the dead, but the dead to summon the living. Wolf’s Troy evokes the oppression of East Germany, while Barker’s brings us visions not only of the women captured by ISIS but, for example, of the current situation of the 1.5 million domestic workers in Saudi Arabia. Among those workers was Tuti Tursiliwati, who was beheaded in October, the punishment for killing her employer in self-defense during one of his repeated attempts to rape her. While Wolf’s Cassandra is the very archetype of the silenced woman, Barker chooses to incarnate perhaps the most overlooked woman named in Homer.

Advertisement

In the Iliad, Briseis isn’t described as “silent.” She doesn’t need to be. Although we see her in Book 1, she doesn’t speak until Book 19. It is not until then, in her mourning speech for Achilles’s beloved friend Patroclus, that we are told anything about her other than that she has beautiful cheeks and that she leaves unwillingly to be transferred to Agamemnon. At last we learn that she is the prize of the man who killed her husband, her father, and her brothers—and yet her only hope for safety for herself and any children she might have is what Patroclus once promised her: marriage to Achilles. Barker skillfully shows us what active political strategies the women construct in their captivity, protecting one another, sharing useful rumors, shrewdly assessing the men’s characters. Their camp life reminds me of the World War II diary A Woman in Berlin, the anonymous account by a German woman of the Russian army’s mass rapes at the end of the war.* She describes how safety lay in forming an exclusive relationship, so as to be less vulnerable to gang rape. In Barker’s scene of Chryseis’s departure, some of the captive women fantasize about taking her place: “To be Agamemnon’s prize…It didn’t come more comfortable than that.”

In The Silence of the Girls, Briseis lives the full range of meanings of the Greek verb damazo, to tame, to domesticate, to subdue, to overpower, to seduce, to rape, to kill. Homer’s Briseis doesn’t describe Achilles slaughtering her male relatives before her eyes, but Barker’s Briseis does. Her eyewitness account is as detailed as a war correspondent’s dispatches. The novel opens with the women of the outlying Trojan town of Lyrnessus, Briseis’s town, crowded into their citadel, knowing that within hours it will fall. They hear Achilles’s battle cry, “inhuman as the howling of a wolf.” Briseis, remembering those hours, recites some of Achilles’s Homeric epithets: “Great Achilles. Brilliant Achilles, shining Achilles, godlike Achilles…How the epithets pile up. We never called him any of those things; we called him ‘the butcher.’” To the women waiting in the citadel, he is what rhetoric would call a hero, but his acts are the acts of what we would call a war criminal:

For once, women with sons envied those with daughters, because girls would be allowed to live. Boys, if anywhere near the fighting age, were routinely slaughtered. Even pregnant women were sometimes killed, speared through the belly on the off chance their child would be a boy…. The air was heavy with the foreknowledge of what we would have to face. Mothers put their arms round girls who were growing up fast but not yet ripe for marriage. Girls as young as nine and ten would not be spared.

The women’s situation becomes even more excruciating as Barker develops the account of their lives in captivity; they not only have to serve their captors sexually, but face, with their differing responses, what it’s like to become the mothers of children by their rapists.

Barker establishes her register at the outset: there is beauty as well as terror in her language, in the physical world she creates, in the changing, unpredictable relationships and situations for the captive Briseis, but Barker keeps her Briseis and Achilles alive in time, not in timeless myth. Barker doesn’t want her readers dazzled or deluded, in the position of the Trojans when Patroclus wears Achilles’s armor into battle: “Once they see the armour, they won’t be able to see past it.” Achilles, like Briseis and Patroclus and the rest of the celebrated epic figures, is seen here not only as a series of embodied actions and achievements, but as someone with a lived past, sculpted by childhood as well as poetry. Barker’s portrait of his relationship with his goddess mother, Thetis, has an edge of dark comedy as well as poignancy: she acquires for him a luxe set of armor made by the god Hephaistos (Agamemnon himself carried a Hephaistos-crafted scepter), but is never there when he needs her. To be the son of an immortal is a bit like being the son of a movie star who gives her child the best of everything but remains a remote figure, an object of longing and of resentment.

Briseis could be compared to King Lear’s Cordelia; she is committed to truth, without which she cannot be herself. She heroically—and silently—refuses to concur in the lie Agamemnon tells Achilles, that he never touched her, even though the falsehood would be to her advantage. But unlike Cordelia, she feels compassion without denying her hatred:

Advertisement

Though I sympathized, almost involuntarily, with men having their wounds stitched up or clawing at their bandages in the intolerable heat, I still hated and despised them all….

It would have been easier, in many ways, to slip into thinking we were all in this together, equally imprisoned on this narrow strip of land between the sand dunes and the sea; easier, but false. They were men, and free. I was a woman, and a slave. And that’s a chasm no amount of sentimental chit-chat about shared imprisonment should be allowed to obscure.

Barker keeps us grounded in the physical realities of war, not just the obvious ones, like the dirt and blood of battle, or the bawdy, drunken chants of men who have survived another day of killing, but in the relationships war unveils: the encounters between patients and doctors, who have to cause pain, and who lie about their patients’ chances, or the way mothers are a ghostly presence on the battlefield, as present as the male ancestors the warriors invoke.

Barker brilliantly sets against Homer’s list of warriors and the glossary of wounds with which Achilles kills them a catalog of their mothers’ efforts to bear and rear them, the struggle to sustain life that also finishes in the dust with their sons’ bodies, without even the compensation of glory. Nor is there any attempt at romance in the physical relations of captor and captive. The men are not transformed any more by desire than by battle; they remain exactly who they are in their sexuality. Achilles isn’t cruel, but “fucked as quickly as he killed, and for me it was the same thing,” as Briseis says.

When Troy falls, Briseis is sent to the same hut where she was captive, now the holding prison of women of Troy. She looks at Andromache, whose small son has been hurled from the city battlements by Odysseus. She will now be the slave of Achilles’s son—the prostitute of the warrior son of the man who killed her husband. Seeing her, Briseis reflects: “Yes, the death of young men in battle is a tragedy…worthy of any number of laments—but theirs is not the worst fate. I looked at Andromache, who’d have to live the rest of her amputated life as a slave, and I thought: We need a new song.”

Herodotus opens his Histories with a brief account of the origins of the Greek and Trojan war:

Abducting young women, in their [the Trojans’] opinion, is not, indeed, a lawful act; but it is stupid after the event to make a fuss about it. The only sensible thing is to take no notice; for it is obvious that no young woman allows herself to be abducted if she does not wish to be.

Barker’s novel has been called a “feminist Iliad”—and, of course, it is, unmistakably; but it cannot be conveniently relegated, as sometimes happens, to a niche of fiction, a genre of retellings by women. It is not only about women’s experience, but about slavery too. And it is also about the nature of knowledge, an exploration of the ways we perceive, and refuse to perceive, reality. The novel deserves to be called an archaeologist’s Iliad: it is as if Barker had found an artifact with an as yet undeciphered alphabet among the glittering grave treasures of Homer’s epic.

Madeline Miller’s novel Circe draws on the Odyssey rather than the Iliad; her book reflects its source. It is a romance, an adventure story, and like the Odyssey, the story of a quest to find a home, this time a woman’s instead of a king’s. Miller’s novel offers a more ample biography of the minor goddess famous in the epic for her love affair with Odysseus, and for her bewitched wine, which transforms the incautious men who visit her island into pigs. In Miller’s story, this is an ironic transformation, since Circe’s power is infused with helplessness: her magic can transform its objects only into their truest selves. Her first effort, with Glaucus, a mortal sailor with whom she falls in love, results in his being revealed as a minor divinity, petty, vindictive, and conceited. Mortals are corrupted by assuming divinity, like mediocre politicians who acquire too much power.

Her second attempt is with her cousin Scylla, who has indifferently stolen Glaucus’s affections. Circe performs this transformation out of jealousy, too inexperienced to understand the consequences. The sexually voracious, amoral Scylla turns into the dreaded sea monster who devours unlucky seamen as they sail the passage between her cavern and the deadly whirlpool Charybdis. But Circe’s own vengeful motivation for Scylla’s metamorphosis means that she shares responsibility for the many men who die to satisfy Scylla’s appetite. By contrast, Circe’s mixture of herbs and wine later finds its mark without guilt when a sea captain and his crew land on her island and violate her sincere hospitality by planning a gang rape of a lone woman they believe to be powerless. It is not Circe who makes them pigs.

Miller’s novel charms like a good bedtime story; she understands our inexhaustible appetite for myths starring our favorite characters, and that we don’t want these stories to end. Her first novel, drawn from the Iliad, was The Song of Achilles, an unabashed celebration of homosexual love whose focus was on the romance of Achilles and Patroclus. She also wrote a delightfully eerie novella about Galatea and Pygmalion, reminiscent of an Edgar Allan Poe tale.

In Circe, she fleshes out familiar and less familiar mythical figures by setting them in fairy-tale situations, giving them domestic lives (we see Daedalus as a devoted family man in thrall to his adorable small son, Icarus, and are introduced to Scylla when she was still a lovely nymph). Miller’s technique echoes Circe’s alchemical powers, as she makes these minor characters more than mere references. She performs a sleight of hand on the gods; instead of figures of ambivalent and shifting grace, favoritism, and destruction in relation to humanity, Miller’s gods for the most part hold human beings in contempt.

The gods are chilling: their immortality makes them incapable of love. They are superhumanly narcissistic, concerned only with being worshiped and satisfying momentary lusts at any expense. The god Hermes explains to Circe that only miserable men give offerings worth having:

Make him shiver, kill his wife, cripple his child, then you will hear from him. He will starve his family for a month to buy you a pure-white yearling calf…. In the end, it’s best to give him something. Then he will be happy again. And you can start over.

Miller has a gift for creating settings that summarize their inhabitants, along with swiftly brushstroked traits and habits that define characters. Circe’s father is the sun, Helios, who lives in an underground palace with obsidian walls. He “liked the way the obsidian reflected his light, the way its slick surfaces caught fire as he passed. Of course, he did not consider how black it would be when he was gone. My father has never been able to imagine the world without himself in it.” Her aunt, Selene, the moon, is a vulgar romantic, roaming the earth at night to spy on lovers and gossiping about them to the gods. Circe, a very low-ranking goddess, is given not a palace but a house on an island that does its own housecleaning and washes its own dishes, a sort of cottage-shaped divinity.

Circe herself is a compound of Cinderella and Hans Christian Andersen’s Little Mermaid—she is the scapegoat in her divine household, with her exotic, bird-like eyes and mortal-seeming voice, teased by her radiant siblings for being stupid and backward, never as at home at the gods’ banquets as they are. And like the Little Mermaid, she is fascinated by humanity and the possibility of being human. She is the only divinity we encounter, aside from her uncle Prometheus (punished for teaching men the nature of fire), who has a moral task to accomplish. She must redeem the destruction her transformation of Scylla has caused; she must become a good witch. And in choosing to learn the arts of sorcery, she is separating herself from the gods: sorcery requires patient work; it can be taught to humans. Witchcraft

is not divine power, which comes with a thought and a blink…. For a hundred generations, I had walked the world drowsy and dull, idle and at my ease. I left no prints, I did no deeds. Even those who had loved me a little did not care to stay.

She is banished to her island precisely because the gods disapprove of and fear witchcraft. Circe is that rarity, a restless, discontented immortal who wants time to pass. And she is a goddess on a quest for significant love.

Miller has learned as many lessons from Disney as she has from Homer, and her story pleases in some of the same ways. The cast of divinities and the impressive parade of Circe’s lovers—Hermes, Daedalus, Odysseus, with whom she will have a child—pass through the book on their adventures like animations. We almost imagine which recognizable voice of which celebrity actor might deliver their speeches. They also tend to speak in the Disney fairy-tale dialect. Here is Circe conversing with the fisherman Glaucos:

“Rise,” I told him. “Please. I have not blessed your nets, I have no powers to do so. I am born from Naiads, who govern fresh water only, and even their small gifts I lack.”

“Yet,” he said, “may I return? Will you be here? For I have never known such a wondrous thing in all my life as you.”

The gods don’t fare as well as humans in Miller’s prose; the former are imagined with less energy and engagement. Brilliant metaphor would be the natural idiom for Circe, whose special power is transformation. Yet even when Athena is on stage, Miller misses her opportunity. Athena alights on Circe’s island “like an eagle in her dive…. She smiled like a temple snake over its bowl of cream,” “looked like an eagle who had been diving upon a rabbit.” Thanks in part to such clichés, Athena is a bore, smug, brutal, imperious.

Miller’s work is most keenly alive in her account of Circe’s parenthood. Here the mutual incomprehension embedded within the relationship of adult and child—experience and naiveté, emotional ambivalence and passion, the sheer amount of divination it takes to meet a child’s daily needs and moods, the shocking power of a fragile baby over a powerful adult—translates beautifully into the descriptions of goddess and child: “A thousand years I had lived, but they did not feel so long as Telegonus’ childhood.” There is a suggestion here of something thrillingly new: the relationship explored between mother and child in these pages is epic, and worthy of epic. It is neither merely mundane nor hopelessly tragic, but dynamic, passionate, tender, angry, dangerous, and loving, with an intense, risky, physical drama played out between a vulnerable child and a mother obligated to be protective even when driven mad in a contest of wills.

It is in these pages that Miller transcends her fairy-tale models, though she returns to them at the book’s conclusion, somewhat predictably, but still poignantly. Miller understands that the best fairy tales are not only wish fulfillments but also stories of the denial of wishes. She manages to combine both elements in her finale, creating an ending that is simultaneously happy and unhappy.

Circe is a novel that will surely be read differently by readers of different ages: an adolescent might very well be powerfully affected by this drama of gods and mortals. For others, like me, the book reads as if it were one of the goddess’s conjuring tricks: a hypnotic experience that seems less like a novel when it is finished than an illusion.

This Issue

December 20, 2018

Damn It All

Prodigal Fathers

In the Valley of Fear

-

*

The author was later revealed to be the journalist Marta Hillers. ↩