A “monster” debuts in a tent show and becomes an overnight sensation. Gawkers jostle for a viewing, journalists angle for takes; in the crowd, expressions of reverent fascination vie with cynical dismissals and racist prurience. The monster says little, but the multiplying chatter tells its own story about the country where, certainly not for the last time, a sui generis American star has been born.

Chang and Eng, eighteen-year-old boys fresh from the Kingdom of Siam, faced their first audience in the ruins of Boston’s Exchange Coffee House in August 1829. Spectators marveled at their long queues and “Oriental” physiognomies, their charm and skill at chess. But the center of attention was the flexible ligament conjoining their breastbones—a nearly six-inch band of flesh that would serve throughout their lives as both tether and passport. Examining it shortly after their arrival, John Collins Warren, later the first dean of Harvard Medical School, pronounced Chang and Eng “the most remarkable case of lusus naturae”—sport of nature—“that had ever been known.”

The Siamese Twins would go on to become their century’s most famous human oddities, eliciting the enduring fascination—along with the pokes, pinches, tickles, and punches—of multitudes. Doctors sounded the mysteries of their union by needling each brother at random, or feeding one of them asparagus and smelling the other’s urine. People called them impostors, tried to convert them to Christianity, asked to examine their genitals; in London, physician Peter Roget, future author of Roget’s Thesaurus, ran an electric current through Chang and Eng to test the passage of “galvanic influence” between their bodies, placing a zinc disc in one twin’s mouth and a silver spoon in the other’s.

The attention must have been similarly shocking. But unlike so many nineteenth-century “freaks,” Chang and Eng parlayed celebrity into a private and prosperous American life. Quickly dispatching their exploitative management, they had earned enough by 1839 to stage a Jeffersonian second act, establishing themselves as gentlemen farmers in Traphill, North Carolina. Quite a distance from their hardscrabble origins in a Chinese-Siamese family of fishermen, Chang and Eng would live to see themselves landowners, husbands, fathers, citizens, slaveholders, and honorary whites.

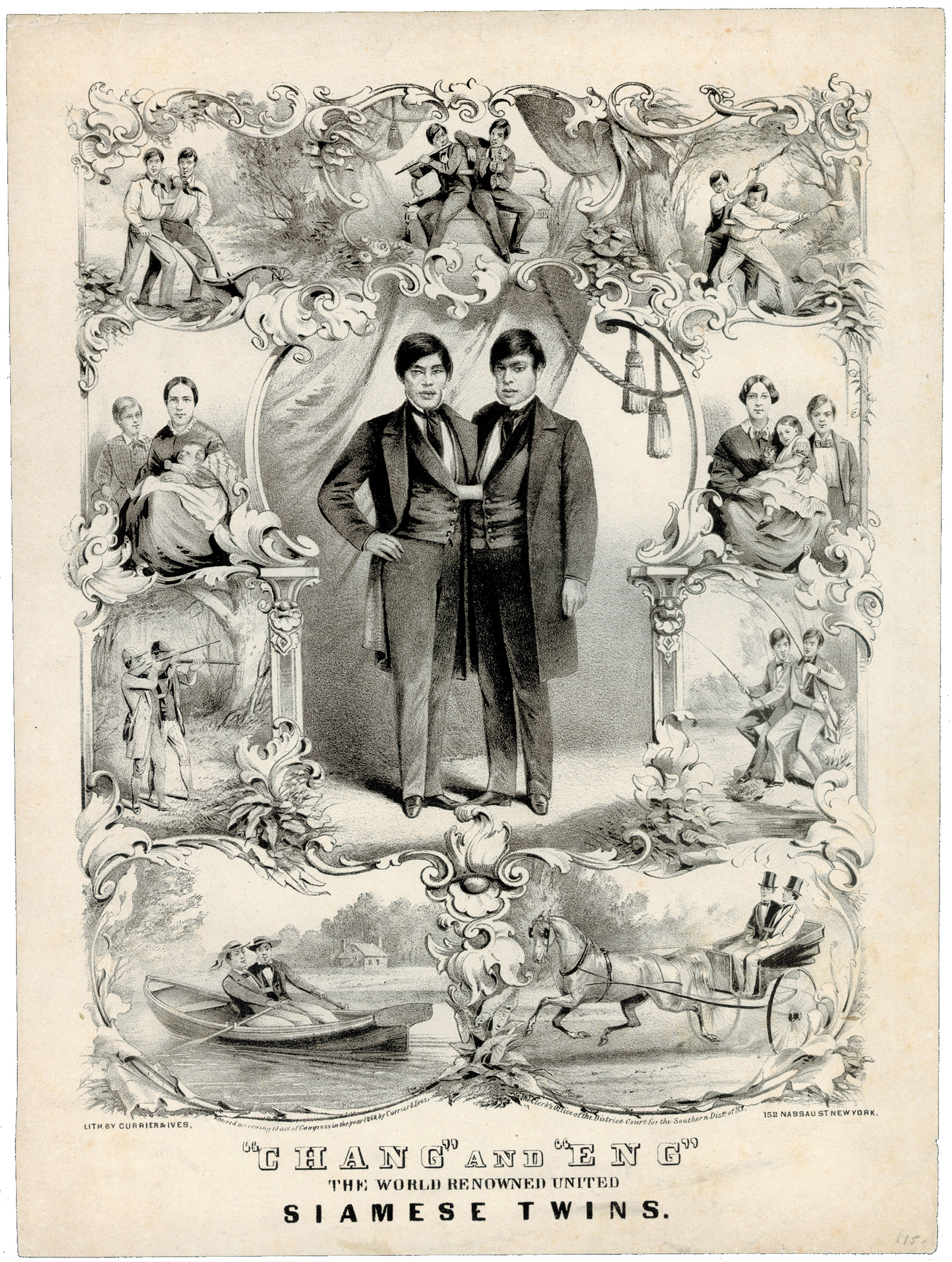

They were pioneers in every sense of the word: Asians in America before the 1848 California Gold Rush; famous performers in a rural democracy yet to be “Barnumized”; and respected patriarchs of interracial families more than a century before Loving v. Virginia. Marrying two white sisters, they adopted the surname “Bunker” and fathered an impressive twenty-one children, two of whom fought for the Confederacy in the Civil War. As cultural figures, Chang and Eng were yet more prolific, begetting no end of scientific studies, metaphysical conundrums, Broadway burlesques, political cartoons, and scandalous exposés. They weren’t always in control of their image, but they sold it, in the form of lithographic portraits, for twelve and a half cents apiece.

Even today, the Siamese Twins require no introduction. They have been featured in The Greatest Showman, a 2017 musical about P. T. Barnum; novels and stories by Darin Strauss and Karen Tei Yamashita; the pages of Merriam-Webster, where the second entry for “Siamese” is “exhibiting great resemblance”; and even the professional lexicon of the fire department. (Nobody wonders if “Siamese connection” standpipes were manufactured in Thailand.) But in a world numbed by spectacle and inured to radical difference, Chang and Eng’s conjoinment itself is no longer astonishing. A condition once considered supernatural, and later a medical marvel, now holds, in the prescient words of one of Chang and Eng’s more cynical spectators, “no more significance” than “a double-yolked egg.”

The nineteenth-century obsession with Chang and Eng’s body now strikes most people as ableist (and, more damningly, quaint). Their career is another story. Two recent biographies trail the twins on their tandem race through history, revealing that their public lives have, unlike their bond, become more interesting. Yunte Huang’s Inseparable is a whirligig vision of nineteenth-century America, the portrait of a young democracy as it saw and was seen by its most unusual citizens. Joseph Andrew Orser’s The Lives of Chang and Eng investigates the twins’ unlikely path to privilege, analyzing the sociocultural forces and “American monsters that Chang’s and Eng’s everyday lives reveal.” Both tell a story that today’s United States—hypersensitive to the craft and commerce of identity, drawn to the hidden truths of marginal lives, regarding its ugliness in the cracked mirror of the Jacksonian Age—feels unusually poised to understand.

What kind of America would Alexis de Tocqueville have discovered had he been, rather than a French aristocrat, a human oddity from another hemisphere? This is the premise of Inseparable, a learned romp more guided by than limited to the story of Chang and Eng. The author, an English professor at the University of California at Santa Barbara, has also edited The Big Red Book of Modern Chinese Literature and published Charlie Chan, an eccentric cultural biography of a fictional Hollywood detective who became a vexed Asian-American legend. Like this earlier work, Inseparable aspires less to narrate a life than reverse engineer a culture. Huang runs the program “Siamese Twins” through a decompiler: in goes the legend, out come the cultural codes, ideological drivers, and pseudoscientific dependency files (in short, the early American operating system) that powered the apparatus.

Advertisement

The book has a picaresque sensibility: like Don Quixote and Sancho Panza, the twins encounter all manner of charlatans, crooks, and credulous fellow travelers while being dogged relentlessly by unauthorized biographies and importunate exploiters. The first was British trader Robert Hunter, weapons dealer to Siam’s King Rama III, who discovered the thirteen-year-olds swimming near their family houseboat in the town of Meklong. Shortly afterward, Hunter and his associate Abel Coffin, an American sea captain, signed a five-year contract with the boys; they left on April Fool’s Day, 1829, for Boston and immortality.

This was excellent timing. Hardly the world’s first conjoined twins, Chang and Eng had the good luck to arrive in a pre–Yellow Peril America, growing by leaps and bounds yet starved for entertainment. (Huang notes that perhaps only two “freaks” had exhibited in America before Chang and Eng—a black man with patches of white skin, probably from vitiligo, and a woman without arms or legs who did needlepoint.) More significantly, they coincided with a critical juncture in the institutionalization of medical research. It was an age when “wonder turned into error, the marvelous into the deviant,” and “medical science…went hand in hand with the institution of the freak show as a business.”

It was not always clear where showmanship ended and serious inquiry began. In London, where Chang and Eng had arrived in November 1829, doctors convened to examine them at a raucous “private viewing party” in the ballroom of Piccadilly’s Egyptian Hall. Phrenologists published competing “portraits” of the twins in newspapers; one concluded that their large “Veneration” faculties, divined by measuring bumps near the top of the skull, corresponded to a typically Siamese religious devotion. On several occasions, small-town doctors eager to prove their expertise harassed the twins in public.

Generally, though, the relationship was symbiotic: Chang and Eng brought doctors prestige and attention, while medicine gave their career a scientific imprimatur. They often toured under the pretext of searching for a doctor to sever their bond. Pamphlets sold at their parlor-room shows reproduced excerpts from doctors’ examinations, a way of reassuring skeptical audiences that the exhibitions were neither fake nor indecent.

A bravura chapter, “America on the Road,” situates the twins in a motley landscape of itinerants. The United States in the 1830s was a “nation on the move,” full of land speculators, Yankee peddlers, and circuit court justices who rode from town to town on horseback. The twins crossed paths with Chief Black Hawk of the defeated Sauk Nation and competed with acts ranging from “Lady Jane the Ourang-Outang” to the firebrand preachers of the Second Great Awakening, whose revivals left towns “literally burned out by religious fervor.”

One of Inseparable’s thrills is the deftness of Huang’s associative leaps. Each chapter is a crank of the kaleidoscope, placing Chang and Eng at the heart of an ever-changing matrix. Digression is the rule; world events scroll past in panoramic miniature; you should not be surprised to meet, in quick succession, Britain’s Queen Adelaide, Liberia’s president Edward James Roye, and the inventor of the artificial anus.

You’d think that Chang and Eng themselves might disappear amid all this context. But the twins assert themselves with irrepressible spirit, proving to be entertainers who courted admiration and faced down hostility with panache. They teased audiences, compared the sun in smoggy London to a lump of coal, criticized the hypocrisy of Christians, and told a preacher concerned with their heathen souls that it was he, not them, who would end up “down dere.”

When attacked, the twins retaliated. In Georgia one of them punched out a country doctor who called them impostors. In Massachusetts Chang and Eng even fired at two men from a mob that accosted them while they were out hunting fowl. These “nineteenth-century equivalent[s] of paparazzi” hurled insults including “damned niggers.” (Asians were so rare in early nineteenth-century America that they didn’t yet merit their own obscenity.)

Independence began with their repudiation of Abel Coffin and his wife, Susan, who controlled the twins’ lives and collected their revenues from 1829 to 1832. The Coffins were Dickensian exploiters of a sententious and paternalistic American variety (think of Miss Ophelia in Uncle Tom’s Cabin, or the Armitages in Get Out). They subjected Chang and Eng to a grueling schedule of travel and performance, ignoring illness and stinting on basic necessities—or, as they thought of it, overhead. The twins were an investment for the morbidly named New Englanders, who took out life insurance on the boys and kept a stock of embalming molasses in case they perished on tour.

Advertisement

There was no love lost between talent and management. In May 1832, at the age of twenty-one, Chang and Eng sent Susan Coffin a blistering resignation letter, a message with all the bite of Jordan Anderson’s famous “Letter From a Freedman to His Old Master.” Denouncing her greed for “hard shining dollars” and scoffing at her maternal pretensions (“The less she says about loving & liking—the better”), Chang and Eng cut off contact and celebrated with a boating trip at Niagara Falls.

Huang’s clear affection for the twins enlivens his account of their independence. But they didn’t remain outsiders and underdogs. In 1839, after seven years of independence, the twins settled down near the Blue Ridge Mountains in Wilkes County, North Carolina. They opened a general store, purchased property in Traphill, and amassed enough social capital to pull off two unbelievable coups: becoming American citizens at a time when citizenship was legally limited to “free white persons,” and marrying two local sisters, Sarah and Adelaide Yates.

Although their 1843 marriages shocked newspapers—“Ought not the wives of the Siamese Twins to be indicted for marrying a quadruped?” wondered Kentucky’s Louisville Journal; the abolitionist Liberator deplored this latest example of Southern depravity—the life that Chang and Eng established was tame. They hunted, fished, raised crops, practiced carpentry, hosted quilting bees, and brought up children.

Though financial exigencies would force them to go on tour in 1849, 1853, 1860, and 1868, the twins spent most of their remaining years at Traphill and, after 1845, a second estate near Mount Airy. Each wife managed a household, and Chang and Eng divided their time equitably between them, mirroring the cooperative system they employed to share a body. When one twin was “in charge,” the other zoned out, a technique one doctor called “alternate mastery.”

Chang and Eng also practiced a more commonplace form of mastery, keeping between eighteen and thirty-two slaves at their two properties. The first slave, a woman named Grace, was a wedding present from their father-in-law, who initially opposed the marriage. Huang doesn’t explicitly remark on it, but I wondered at this coincidence of slave ownership with sudden nuptial legitimacy: “One of the many miraculous things a slave could do,” writes the historian Walter Johnson in Soul by Soul, “was to make a household white.”

Huang is unfortunately fuzzy about the moral implications. Though he doesn’t omit the known details—Chang and Eng sold off boys who reached maturity, and once even played for slaves at cards—he repeatedly insists on a misleading symmetry between the twins’ experience and that of their captives. Juxtaposing Chang and Eng’s “emancipation” with the Nat Turner rebellion in a bathetic five pages, Huang claims against all evidence that the Bunkers were “treated no better than slaves.” (What slaves signed contracts, sent sarcastic letters to their employers’ wives, or brawled with white men and then mocked them in court?) By way of mitigation, Huang invokes Primo Levi’s “‘gray zone’…a treacherously murky area where the persecuted becomes the persecutor, the victim turns victimizer.” The analogy is unconvincing. Levi’s “gray zone” was populated by Jewish collaborators in the Holocaust, not “honorary whites” who, though harassed by xenophobes, were never enslaved.

The problem isn’t just one of false equivalence. Vague on the moral why behind Chang and Eng’s ascension to the oppressor class, Huang ends up shortchanging the question of how they rose. His story of luck, determination, and all-American oddity can make the twins’ trajectory feel like the result of happenstance. For all Inseparable’s narrative exuberance and delightful, Melvillean erudition, it left me wondering about the twins’ hustle—their motives, means, and the social forces that governed their lifelong game. Conjoined Asian “freaks” didn’t become rich white citizens by accident in 1830s America. How did Chang and Eng Bunker play their unusual hand?

Joseph Andrew Orser’s The Lives of Chang and Eng doesn’t aspire to Inseparable’s range. Where Huang rollicks, Orser moves like a land surveyor, triangulating the territory where the twins staked their unlikely claim. Attentive, like any good surveyor, to the forces shaping this fraught landscape, he recounts Chang and Eng’s precarious traversal with penetrating insight. The focus is on how the twins maneuvered across the fraught ground of American identity.

The Siamese Twins of Orser’s narrative come across as savvy public figures, swiftly angling for a respectable position in their adopted country. They refused to be sentimentalized as the Coffins’ Oriental wards: in a flattering newspaper “dialogue” for the New York Constellation in 1831, the twenty-year-old twins chastised a visitor who called them boys, a term loaded with classist and colonial implications. “Boy is a boy,” said Chang, “a servant boy—cook boy—school boy.”

The twins gave money to beggars at public appearances, “us[ing] the poor and unfortunate as the pivot on which to leverage themselves into a leisured gentlemanly position.” Once under their own direction, they consciously solicited middle-class attention by exchanging their somersault routines and “Eastern” costumes for parlor-room banter and Western dress. Starting in 1849, they enlisted their families in the act, exhibiting from San Francisco to London with their wives and children. The marvel was that the Siamese Twins were normal, respectable Victorian patriarchs—though not so normal that the fact itself ceased to be marvelous.

Identity politicians avant la lettre, Chang and Eng and their promoters also modulated their racial self-presentation to accommodate American attitudes. Orser notes that while an 1829 pamphlet depicts the twins amid huts and palm trees as unregenerate Siamese natives, 1836 and 1853 booklets produced under their direction emphasize their Western social attainments and Chinese paternity. (Chang and Eng were lukjin, born into Siam’s Sino-Thai minority.) Orientalist writers on Siam considered its people “copies…of lesser quality” when compared with their Chinese “originals.”

Thomas W. Strong, author of the 1853 pamphlet, considered the twins’ Chinese heritage downright American: “[The Chinese] may be justly termed the Yankees of Asia, for their migratory propensities, as well as their aptness in striking a bargain.” Strong’s pamphlet also recounted Chang and Eng’s service as ambassadors for the King of Siam—an episode entirely plagiarized from a British memoir. However far from reality, “patrician” ideas of the noble East lent Chang and Eng plausibility as American gentry; an 1860 lithograph portrays Chang and Eng haloed by inset scenes of leisure and family life (see illustration on page 24).

Among Orser’s more counterintuitive insights is his claim that Chang and Eng’s Southern community insulated them from various forms of prejudice. Above the Mason-Dixon Line, industrialization, immigration, and growing class divides had strengthened the boundary between “the lily-white order of the private sphere and the motley hue of public disorder.” Minstrel shows proliferated, along with the usual urban contempt for itinerant entertainers. By contrast, in small-town North Carolina, Chang and Eng could leverage personal friendships and property ownership to become leading citizens.

Even so, sectional acrimony and the white backlash to Chinese immigration damaged the twins’ carefully wrought self-portrait. In his 1855 California travelogue The Land of Gold, Hinton Rowan Helper, a white North Carolinian, denounced the Chinese as arrogant, amoral, and “xanthous”—yellow, which quickly became a slur. Over the next three decades, anti-Chinese persecution accelerated and proliferated, culminating in the 1882 Chinese Exclusion Act. Anti-Chinese racism also figured in the debate over slavery. Southern apologists contended that California’s new arrivals were owned by mandarins across the Pacific, and that “Chinese peonage” betrayed the hypocrisy of “free” states. For their part, some anti-slavery writers, including Helper, cut their moral outrage with healthy doses of xenophobia. Slavery was evil not only for what slaves suffered, but for maintaining alien others on American soil.

Allegorists personified these intensifying divisions in images of Chang and Eng. An 1863 Broadway show featured two scammers who impersonated the twins, one a black freedman and the other an Irish immigrant. In 1860 the New York Tribune editorialized that “The ‘Union’ [was] in Danger—Chang threatens to secede…Dr. Lincoln…gave his opinion that the operation would be dangerous for both parties.” After the war, Mark Twain’s satire “Personal Habits of the Siamese Twins” aspirationally compared Chang and Eng to the painfully reconstructed nation.

In truth, they shared its injuries. The victorious Union had emancipated their slaves and vaporized their financial capital, comprised almost entirely of Confederate treasury bonds that they later sold to collectors by the pound. Throwing themselves on the charity of Northerners (“The ravages of civil war have swept away our fortunes,” they announced in The New York Times, “we are again forced to appear in public”), Chang and Eng resumed public exhibitions with their families, submitting to indignities like partnering with Barnum, whom they despised, and concluding their last, dismal European tour at a Berlin circus. In Britain, one visitor mortified Chang’s daughter Nannie by asking if her “grandmother or grandfather was a negro.”

In Orser’s succinct phrasing, the twins’ “claims to whiteness had just about expired.” When they died at home in 1874, four years after Chang suffered a stroke while playing chess with the president of Liberia on a steamship, The New York Sun’s obituary compared their “repelling” faces to “those of the Chinese cigar sellers of Chatham street.” Orser’s last and strongest chapter, “Over Their Dead Bodies,” details the macabre frenzy with which neighbors descended on the bereaved Bunker estate. A “camp meeting” atmosphere set in as neighbors who had previously treated the twins as ordinary citizens scrambled for a piece of their legacy.

Asian marvels who became American planters, in death Chang and Eng returned to being freaks. Frightened by the doctors and curiosity collectors who clamored “Name your price,” Sarah and Adelaide hired a tinsmith to seal their husbands in a soldered doublewide coffin. Only an intervention from the family doctor, who invoked high-minded scientific ideals, convinced them to reopen it for a postmortem; he also warned that if the widows didn’t turn over the body, grave robbers would surely dig it up. Over the objections of their children, the more distant of whom didn’t receive word in time, Sarah and Adelaide relented.

The doctors who conducted Chang and Eng’s autopsy took only a few liberties. They returned the twins to North Carolina for burial, but stole the conjoined liver, which they preserved in a tub of formalin. It remains on display, alongside a plaster cast of their bodies, at Philadelphia’s Mütter Museum.

The American nineteenth century has increasingly become the freak of the twenty-first. Partisans relitigate the Civil War while preparing for its sequel; critics find precursors of fake news in Jacksonian “humbug”; steamships, telegrams, and crackpot innovations provide convenient analogues to the world-shrinking disruptions and robber-baron swindles of our own digital dystopia. Most pertinently, the nineteenth-century spectacle of race and abnormality has come to seem like a strange forerunner of today’s identity-based cultural economy, increasingly powered by the brisk commodification of difference.

Drawing on studies of minstrelsy, the writer Lauren Michele Jackson has explained how GIFs frequently turn images of black people into all-purpose expressions of “animated” emotion, a pervasive form of “digital blackface” that white supremacists have turned to hateful ends. (After the 2016 election, trolls mocked “triggered” people of color with memes of a crying Michael Jordan.) The phenomenon fits into a long American tradition—beginning, perhaps, with the ersatz Indians of the Boston Tea Party—of transgressing social norms from behind the masks of others. So it was with Chang and Eng, whose condition and foreign origins made them instant stars yet semiotic blanks. They were human extremes who became endlessly adaptable vernacular universals; in short, they became memes.

In the Internet Age, each one of us risks becoming a lusus naturae. Virality turns the “freak” of a moment into the public’s expressive instrument, with unpredictable consequences for the individuals represented. If there is anything uniquely fascinating about the Siamese Twins in such an era, it might be the way they anticipated this dynamic, the power they gleaned by participating in their own commodification. Their path to the American dream, unusual in their century yet definitive for the twentieth and twenty-first, consisted of selling their difference in public to secure freedom in private.

Tyehimba Jess’s Pulitzer Prize–winning collection Olio distills the bittersweetness of such bargains in a series of poems on Millie and Christine McKoy, conjoined African-American sisters who sang harmonies and played keyboard duets. Born slaves in North Carolina but emancipated at eleven in 1863, they performed as “The Two-Headed Nightingale,” earning worldwide fame and eventually settling down on the very farm where they’d been enslaved. Imagining their feelings, Jess arrives at a resigned acceptance that applies as much to our world as it does to the McKoys’ particular predicament: “Thus, we buy liberation/from each gawking crowd.”